CHAPTER VIII

THE GUARDIANS

"Why, what, which—" cried Hackett, looking wildly in the direction from which the missiles came. "Must be those fellows again."

"We'll show them they can't frighten us!" burst out Bob.

Just as he spoke, a ball of the feathery particles sizzled through the air, struck him forcibly on the shoulder, and splattered in his face.

"Just a bit of a lark, I guess!" cried Bob, "but it shouldn't be so one-sided. Come on, fellows!"

With one accord, they dashed through the snow, which, though the night was dark, could be plainly seen. In a moment, they reached the base of the hill, and rounded the other side.

Nothing there—but a wild expanse of nature, melting into gloom, gaunt trees and underbrush—nothing but night and an icy wind sighing through the tree-tops and making the bushes shiver and rattle.

"My eye! This is funny," cried Hackett, scratching his head.

"Christopher! It's the strangest yet," panted Nat. "Where did he get to—or where did they get to?"

"That's what we would like to know," said little Tom Clifton.

"An axiom," observed Dave, "is a self-evident fact."

"Did an axiom make the snowballs, fire 'em over, and plunk Somers in the face?" grinned Hackett.

"No, but somebody did, which is the axiom I mean."

"Hi—hi!" yelled Hackett. "Come out and show yourself—come up and toast yourself. You must be nearly frozen out there!"

Nothing but silence followed the echo of Hackett's voice.

"This certainly is funny," said Bob.

"That's what we all said before, my boy," observed Dick. "It must be those campers on the other side, as Hackett says."

"Well, they have cleared out, and we might as well get back to the fire," said Nat.

"Must be a lot of jokers around these parts," ventured Tom Clifton.

"Now they have had their fun, why don't they come out, and show themselves?" added Sam Randall.

There was no answer to this—and for obvious reasons.

So they tramped toward the fire, which flashed between the trees like a beacon, discussing the singular affair, with the rather unpleasant feeling that any minute a snowball might land upon the back of somebody's neck.

Logs were piled on the blaze, and the unfortunate coffee-pot refilled.

Very wisely, after some discussion, the boys decided to let time solve the mystery, so they told stories and kept on trying to warm the side which was always cold.

Occasionally from the woods came the hoot of an owl, or over the lake the weird cry of a loon.

Hackett was kindly allowed to finish the story of his prowess, after which, whether the result of his tale or not, there was an amazing amount of yawning and stretching.

"Oh, ho, even if it is only half-past eight, I'm going to turn in," announced Dave. "Good-night, fellows."

"Think I will, too," declared Sam.

"We can get up early and put in a good day to-morrow," added Nat.

"And get a shot at something worth while," commented Hackett. "Just let some of you fellows feel what buck fever is like."

"What is it like, 'Hatchet'?" asked Tom.

"Who said I ever had it? I'll take my chances with the next one—and don't you forget it."

"Did you ever see a deer outside of a wire fence?"

"My eye! But you do ask a lot of silly questions. Just let me draw a bead on one, eh, Nat?"

"That's right, Hacky," grinned Nat, as he started for the hut.

It did not take the rest of the fellows long to follow his example. Within a few minutes, the fire was deserted, and each had retired to his bed of fir brush.

It seemed to little Tom Clifton that he had been asleep but an instant, when he was awakened by the sound of voices and the tread of feet. The boy felt a strange sort of thrill run through him. With beating heart, he listened intently.

"Maybe somebody is going to play another joke on us," he thought. Then another idea suggested itself, which gave him an unpleasant start. "Perhaps the newcomers had a more serious object in view."

But while he was speculating on the possibilities, a sound close to the hut made him sit upright. An animal was plainly sniffing around.

The next instant, Tom was terrified to see the canvas flap pushed back, and a huge head thrust inside. To his excited imagination, it looked more like a bear than anything else, and, with a startled cry, he threw off the blankets and rose tremblingly to his feet.

Bob and Dave Brandon started up just as a deep bay from the huge animal seemed to make the very interior shake.

"Great Cæsar!"

"By Jingo, what's this?"

The two boys were on their feet in an instant, while the animal, with another tremendous bay, hastily withdrew its head.

"It's only a dog!" cried Bob, beginning to laugh.

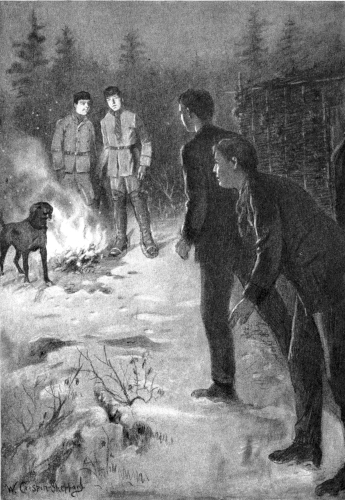

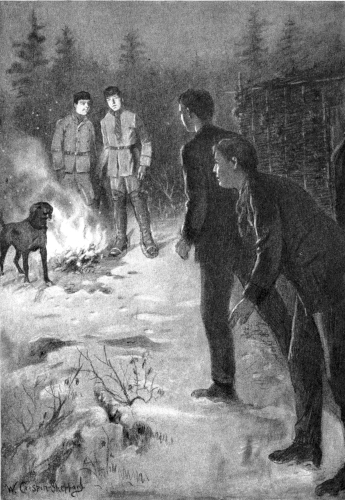

Before the camp-fire, which, piled high with fuel, was springing into life again, stood two dark figures, who viewed with unconcern the precipitous exit of seven boys from two huts.

The big animal had rushed to one side, where its eyes shone like two orbs of green light from the darkness.

"Hello!" exclaimed one of the strangers.

"HELLO!" EXCLAIMED ONE OF THE STRANGERS

"Hello!" cried Bob.

There was a hearty, boyish ring about the voice of the newcomer that dispelled all fears from Tom Clifton's mind.

The fire blazed up, revealing plainly the faces and figures of the visitors. The one who had spoken was a bit taller than his companion, with wide, strong shoulders, brown, curly hair, a pleasant face and very red complexion. The other was short and stocky, with a mouth that approached astonishingly close to his ears, a decidedly stubby nose, and cheeks big and round.

It was an odd face—an amazingly impudent face, that surveyed the boys with a comical grin, and one that seemed to invite antagonism. His voice, too, which the boys presently heard, was loud and boisterous.

"Why, these must be the lads your dad told us about, Tim," he exclaimed.

Hackett's face darkened.

"Look here!" he exclaimed, abruptly, "didn't you chaps fire a lot of snowballs at us a while ago?"

"Fire a lot of snowballs at you?" repeated the newcomers, looking from one to the other in apparent surprise. "What do you mean?"

"Just what I said."

"No! Of course not—just got here," spoke up the taller boy, unceremoniously piling wood on the blaze. "Hi—get away, Bowser—lie down." Then he added, "My name's Sladder—Tim Sladder, and this is my friend, Billy Musgrove."

"Sladder—Sladder," repeated Hackett. "Sounds kind of familiar. Ah, yes, I remember. Why—say—you must be the son of Hiram Sladder, of the Roadside House."

"You've guessed it," grinned Billy Musgrove.

"Well, how on earth, or how on snow, did you manage to find us?" asked Nat Wingate, with interest.

Musgrove laughed. It was a particularly loud and irritating laugh. He threw back his head and laughed again, although none of the boys could quite understand what there was to excite his merriment.

"It was this way," he began.

"Hold on, Billy; I'll tell it," broke in Tim Sladder. "Get out, Bowser. You see, pop told me all about your coming to the hotel, an' he says—"

Another laugh came from Billy Musgrove.

"An' he says, 'I told 'em whereabouts to go—Lake Wolverine. But them fellers, says I, ain't no hunters. If they don't get chewed up by wolves or wildcats, or get froze, or lost in the woods, or if something don't happen to 'em, I miss my guess, an'—'"

"I call that pretty cool," interrupted Hackett, in fierce tones.

Tim Sladder went on, "You must be the long-legged feller pop spoke about. He—"

"Is it cold up there?" blurted out Musgrove, with another laugh.

"See here—" began Hackett, angrily.

"Now, Billy Musgrove an' me's been a-wantin' to take a trip for a long time," resumed Tim Sladder, "so I says to mom, 'Why can't we go out huntin' an' trappin', an' sort of keep an eye on 'em?' an' she says, 'Just the thing an'—'"

"My eye!" put in Hackett, angrily, "I like that—I do, indeed. What do you think we are, anyway—a lot of two-year-olds?"

Musgrove laughed, while Tim Sladder surveyed the speaker for some moments in mild astonishment.

"I'm only tellin' you how we happened to come along," he continued. "Billy Musgrove an' me's got a bully camp up the lake a bit. We seen the light of your fire—get away, Bowser—an' didn't know but what it might be you fellows. So we walked over."

"And you've got the job of looking out for us, eh, Tim?" laughed Nat. "And that big four-legged brute is going to help?"

"Bowser's a corking good dog—he is."

The owner patted the head of the great hound. "Mild, when he knows you—have to be a little careful, at first. Lie down, Bowser. Say, are you coming over to see our camp to-morrow?"

"If you do," chimed in Musgrove, "we'll show you some real sport."

"What kind?" asked Hackett, with a show of interest.

"Come over an' see! Say, can you fellers skate?"

Hackett grinned.

"If there is anybody around here who can beat me, I'd like to see him."

Musgrove's loud laugh again rang out.

"As good at that as bowling over wildcats, eh? Ha, ha! Tim's dad says as how you could fix 'em. Well—I'll race you. Say, what's your name?"

The light playing on Musgrove's face displayed a grin of enormous dimensions.

The boys tittered, that is, all except the tall youth, who scowled ominously. He was quite unable to fathom Billy Musgrove's manner, or to determine whether his dignity was being assailed or not.

"John Hackett," answered the owner of that name, after a short pause.

Then the other Kingswood boys introduced themselves.

"Well, I'm glad we found you," said Tim Sladder, cheerfully. "I told mom we would. Guess we'll hike back to camp now. Don't forget to look us up to-morrow—so long, fellows! Come on, Bowser."

Both shouldered their guns and started off, at intervals Musgrove's laugh ringing out.

"Mighty funny fellows, I call 'em," said Nat. "Isn't it odd that we should meet that great hunter, Tim Sladder? And it's an 'undeniable fact' that Billy Musgrove is a cool one. Hasn't he the biggest mouth you ever saw?"

"He needs to be taken down a peg or two," growled Hackett. "Little, sawed-off turnip thinks he can skate, eh? I'll show him. The nerve of the chap—'Say what's your name?' I had a mind to flop him in the snow."

"Oh, ho!" laughed Dave; "to flop one of our guardians in the snow, that's too much. I'm going to turn in.”