CHAPTER XXI

Toni and Denise had selected for their wedding day the anniversary of the marriage of Paul and Lucie two years before. The wedding was as fine as Lucie could make it, and she had great capabilities in that line. The garrison chapel was decked with flowers, the organ played, and it was much more like the wedding of a lieutenant than a corporal—Lucie paying for it all. Madame Marcel came from Bienville to the wedding and was resplendent in a purple silk gown, a lace collar and a bonnet with an aigrette in it. She looked so young and handsome that, together with the sale of her piece of land, she wholly dazzled the sergeant, who speculated on his chances of leading her to the altar sometime within a year.

Mademoiselle Duval treated herself to a new black gown and a very forbidding-looking black bonnet, but really presented an elegant though austere appearance. Denise’s white wedding gown was made with her own fingers, and, although it was only a simple muslin, never was there a daintier looking bride in the world than the sergeant’s daughter.

In the first row of seats in the church sat Paul and Lucie, the latter charmingly dressed in honor of the occasion. The chapel was filled with humbler people, friends of the bride and bridegroom. The bride, with her father, the sergeant, arrived in great state in Lucie’s victoria and pair and the same equipage—the handsomest in Beaupré—carried the newly-married pair back to the large room in one of the plain but comfortable hotels of the place, where a wedding breakfast was served.

Toni was not at all frightened at the imminent circumstances of the day. On the contrary, he felt a sense of protection in marrying Denise. She would always be at hand to take care of him, for Toni felt the need of being taken care of just as much, in spite of his five feet ten, and his one hundred and fifty pounds weight, and his being the crack rider in the regiment, as he had done in the old days at Bienville when he ran away from the little Clery boys. He did not, therefore, experience the usual panic which often attacks the stoutest-hearted bridegroom, and went through the wedding breakfast with actual courage. He absolutely forgot everything painful in his past life. Nicolas and Pierre melted away—he did not feel as if they had ever existed. The secret which had haunted him was a mere fantasy, that vanished in the glow of his wedding morning.

Paul and Lucie came in during the breakfast and Paul proposed the bridegroom’s health with his hand on Toni’s shoulder, Toni grinning in ecstasy meanwhile. Paul spoke of their early intimacy, and Toni made a very appropriate reply—at least Denise and Madame Marcel thought so. After the lieutenant and his wife had left, the fun grew fast and furious. It was as merry a wedding breakfast as Paul’s and Lucie’s, even though the guests were such simple people as would come to the corporal’s wedding with the sergeant’s daughter. Toni could have said with truth that it was the happiest day of his life.

When the wedding party dispersed, and they returned to the Duvals’ lodgings that the bride might change her dress, the sergeant, being left alone in the little sitting-room with Madame Marcel, grew positively tender, saying to her in the manner which he had found perfectly killing with the girls twenty-five years before:

“Now, Madame, that we have seen our children happily married we should think somewhat of our own future. The same joy which those two children have may be ours.”

Madame Marcel, who had heretofore received all the sergeant’s gallant speeches with an air of blushing consciousness, suddenly burst out laughing in a very self-possessed manner, and said:

“Oh, we are much too old, Monsieur; we should be quite ridiculous if either one of us thought of marrying.”

The sergeant received a shock at this, particularly as he considered himself still young and handsome.

“My dear Madame Marcel,” he replied impressively, “certainly age has not touched you and I flatter myself”—here he drew himself up and twirled the ends of his superbly-waxed mustaches—“that so far time has not laid his hand heavily on me.”

“If you wish to marry, Monsieur,” replied Madame Marcel, still laughing, “you ought to marry some young girl. Men of your age always like girls young enough to be their daughters,” and she laughed again quite impertinently.

The sergeant frowned at Madame Marcel. He had never seen this phase of her character before.

“I assure you, Madame,” he said stiffly, “that if I care to aspire to the hand of a young woman of my daughter’s age, I might not be really considered too old; but I prefer a maturer person like yourself.”

Madame Marcel, seeing that the sergeant was becoming deeply chagrined, determined not to dash his hopes too suddenly, so she reassumed her old manner of girlish embarrassment and said:

“Well, Monsieur, one wedding makes many, you know; but a wedding is a fatiguing business to go through with, particularly at our age. It will take us both, at our time of life, several weeks to recover from this delightful event and we may then discuss the project you mention.”

This was slightly encouraging, and as the sergeant had nothing better to comfort himself with he contrived to extract some satisfaction from it.

When Denise appeared, dressed in her neat gray traveling gown, the Verneys’ handsome victoria was at the door to take her and Toni to the station. Toni and Denise felt very grand, as well as very happy, sitting up in the fine victoria with the pair of prancing bays, and although they were conscious that the footman and coachman were thrusting their tongues into their cheeks, it mattered very little to Denise and Toni, whose black eyes were lustrous with delight. At last, he reflected joyously, he had some one who would be obliged to look after him the rest of his life.

When they reached the station the train was almost ready to depart. Toni had wished, on this auspicious day, to travel to Paris second-class, but the prudent Denise concluded that as they would go through life third-class they had better begin on that basis. So Toni selected a third-class carriage which was vacant and, tipping half a franc to the guard, he and Denise found themselves in it without other company. It was their first moment alone since they had been made one. Toni put his arm around Denise and drew her head on his shoulder with the strangest feeling in his heart of being protected, and Denise, for her part, had the sense of having adopted this fine, handsome, laughing fellow, to shield under her wing the rest of her life. Yet they were lovers deep and sincere. No French gentleman had ever treated his fiancée with greater respect than Toni, the corporal, had treated Denise, or ever had a higher rapture in their first long kiss.

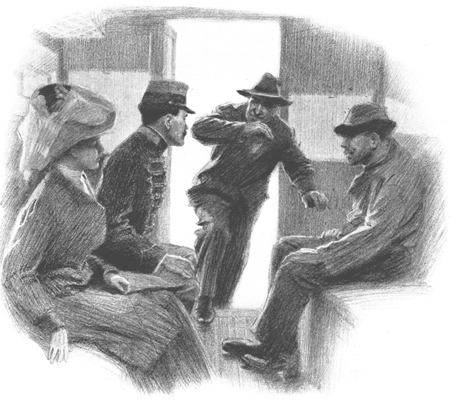

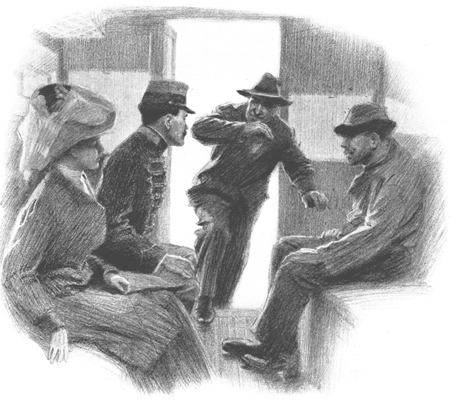

He was roused from his dream in Paradise by the consciousness of a sinister presence near him, and his eyes fell on the red head of Nicolas peering like the serpent in the Garden of Eden in at the window of the railway carriage. If the place of eternal torment had yawned before Toni’s eyes he could not have felt a greater horror. And this was increased when Nicolas coolly opened the door of the carriage and got in, followed by Pierre, and the two seated themselves directly opposite the newly-married pair. Almost immediately the train moved off. Toni had only one thought in his mind—to keep Denise from finding out that terrible secret of his—why he hated and feared these men. He hated and feared them now more than ever, but some new courage seemed to be born in him. The cardinal difference between a brave man and a coward is that a brave man can think when he is afraid and can even act sensibly, and a coward can not do either. Always before this when he had been frightened, Toni had acted like a fool, but now he acted as sensibly as Paul Verney himself could, and for once behaved bravely, although he was contending with men instead of horses. The two rogues opposite him leered at Denise, nudged each other, and Pierre held out his hand to Toni.

“Seated themselves directly opposite the newly married pair.”

“How do you do, comrade?” he said.

For answer, Toni folded his arms and looked at the extended paw with disgust.

“No, I thank you,” he replied, in a voice as steady as if he were managing a vicious brute of a horse. “Denise, don’t look at them, my dear,” and he motioned her to sit with him in the furthest corner of the carriage.

Denise surmised who these two individuals were, but said nothing, only averting her eyes from them. Nicolas then persisted in trying to converse.

“We are back from Algiers,” he remarked impressively.

“It doesn’t require a genius to know that,” Toni answered tartly. “It’s a great pity you were not kept there for ever.”

He felt astonished at his own boldness in saying this, and the devil of fear, taking on a new guise, made him afraid of his own boldness. But, at all events, he felt that there was no danger of his betraying himself then before Denise. Nicolas and Pierre continued to wink and make remarks, evidently directed at Denise. Toni stood it quietly, but the first time the guard passed he spoke to him.

“These two fellows,” he said, “are impertinent to my wife. At the first station I would thank you to put them in another carriage.”

The guard had seen the fine style in which Toni had driven to the station with his bride, and also respected Toni’s smart corporal’s uniform, so he bowed politely and said, “Certainly,” and the next station being reached in two minutes, Toni had the satisfaction of seeing his two friends unceremoniously hauled out and thrust into another carriage which was before nearly full. As they went out Pierre laughed—a laugh terrible in Toni’s ears.

“You haven’t been very polite to us,” he said, “but we shall meet again. Remember I promised you that when we parted two years ago, and we never go back on what we say.”

This troubled Denise and when they were alone Toni told her as much as he thought well for her to know of Nicolas and Pierre, but it was not enough to disturb her very much on her wedding journey. Toni, however, again felt that old fear clutching and tearing him. His courage had been merely outward, and outward it continued. He was apparently the most smiling and cheerful bridegroom in the whole city of Paris, but no man ever carried on his heart a heavier load of anxiety and oppression.

Madame Marcel had given Toni a little sum of money which was quite beyond his corporal’s pay for his wedding tour, and they had taken a little lodging in the humbler quarters of Paris, and here they were to spend the precious week of their honeymoon. It was still bright daylight at seven on a June evening when they reached their lodgings and removed the stains of travel. Toni, in the gayest manner possible, proposed that they should take a stroll on the river bank before going to their supper. It was a heavenly evening and a gorgeous sunset was mirrored in the dancing river as Toni and Denise leaned over the parapet of the bridge of the Invalides, holding each other’s hands as they had done when they were little children sitting on the bench under the acacia tree at Bienville. Toni could have groaned aloud in his agony. He would be the happiest creature on earth if only those two wretches had not appeared. He was happy in spite of them, but then the terrible thought came to him that they had promised to kill him and Paul Verney, too, and they were of a class of men who usually keep their word when they promise villainy. He felt an acute pang of sorrow for Denise and an acute pang for himself and for Paul and Lucie—so young they all were, so happy, and that happiness threatened by a couple of wretches who would think no more of taking a man’s life than of killing a rat, if they had the opportunity.

He looked at the crowds of gaily-dressed people which filled the streets with life. He looked at Denise in the charming freshness of her youth, her tender eyes repeating with every glance that she loved Toni better than anybody else in the world. He considered all the splendor and beauty around him—the dancing river and the great arched, dark blue sky above them in which the palpitating stars were shining faintly and a silver moon trembled—and he could scarcely keep from groaning aloud at the thought of being torn from all he loved. But he gave no outward sign of it. Denise thought him as happy as she was.

After their supper at a gay café they came across one of those open-air balls which are a feature of Paris, and they danced together merrily for an hour. Everybody saw they were sweethearts and some jokes were made at their expense, which Toni did not mind in the least and would have enjoyed hugely, but—but— Afterward they walked home under the quiet night sky. In place of their gaiety and laughter a deep and solemn happiness possessed Toni as well as Denise, except for this terrible fear, black and threatening, which would not be thrust out of his happiest hours.

Paris in June for a pair of lovers on a honeymoon trip, with enough money to meet their modest wants, is an earthly Paradise. Denise loved to exhibit her muslin gowns, made with her own hands, by the side of her handsome corporal, in the cheap cafés and theaters which they patronized. They found acquaintances, as everybody does in Paris. The lodging-house keeper became their friend and invited them to her daughter’s birthday fête. They went out to Versailles on Sunday and saw the fountains plashing, studied the windows of the magnificent shops in the grand avenues, and were perfectly happy, except for the black care that sat upon Toni’s heart. Life could be so delightful, thought Toni, but his would end so soon. Toni almost felt the knife that Nicolas would stick into him. He pondered over the various ways in which he might be killed—a blow like that which felled Count Delorme might do for him. He imagined himself found dead in the streets of Beaupré some dark night, and the story of how he came by his death would never be known. And he thought of Paul—that his body might be found in a thicket of the park of the Château Bernard, just as Count Delorme’s had been. Toni was an imaginative person and the horror of his situation was enhanced by the Paradise of the present. He wondered sometimes how he managed to keep it all from Denise, but he did for once.

Too soon the time came when he had to return to Beaupré. It was on a wet and gloomy day that he and Denise alighted from a third-class carriage at the little station. They walked straight to their modest lodgings, and then Toni went to seek Paul. His leave was not up by several hours, so he need not report at once. He found Paul at the headquarters building in a little room where he worked alone. When Toni came in and shut the door carefully behind him, Paul whirled around in his chair expecting to see a radiant, rapturous Toni. Instead of that, Toni dropped the mask which he had worn before Denise and looked at Paul with a pair of eyes so distressed, so haunted, so anxious, that Paul knew in a moment something had happened.

“Well, Toni,” he began, and then asked, “What is the matter?”

Toni, instead of standing at attention, leaned heavily against the desk—his legs could hardly support him.

“The day I was married,” he said, “when Denise and I got in the railway carriage to go to Paris, Nicolas and Pierre got in, too.”

Paul’s ruddy, frank and smiling face grew pale as Toni said these words. They might mean for him, as well as for Toni, a decree of doom, and, like Toni, he was so happy that the thought he should be torn away from it all seemed the more cruel.

“And what did they say and do?” he inquired after a painful pause.

“They were very insulting at first to Denise, but I told her not to notice them, and they wanted to shake hands with me, but I refused.”

“Did you?” cried Paul, in amazement. “Is it possible that you didn’t act like a poltroon and shake hands with them and do whatever they asked you to do?”

This was no sarcasm on Paul’s part, but a plain expression of what he expected Toni would do, and Toni was not at all offended at this imputation on his courage and good sense.

“Yes,” he said, “I acted the man with them. I never did it before, but I did more than that—I called the guard, who made them go into another carriage.”

Paul gazed at Toni with wide-eyed surprise. Here was the most astonishing thing that ever happened—Toni actually showing a little courage with these men.

“I can hardly believe it is you, Toni, standing before me. If you had shown the same spirit all the time, you would not now live in dread about that Delorme affair.”

“Perhaps not,” sighed poor Toni, “but you know how I always was, Paul.”

“I think you are going to be something different now,” replied Paul cheerfully. It was not pleasant—the thought that these two rascals, who had promised to kill him as well as Toni, were alive and in Paris, but Paul’s nerves were perfect and he easily recovered his balance.

“But the thought of it—the thought of it!” cried Toni, opening his arms and standing up straight. “The knife entering my breast or that blow on the side of the head such as they gave Count Delorme. I feel them and see them everywhere I look. If I see a man walking on the street he seems to take the shape of Nicolas or Pierre. Every time I turn a corner I expect to see them. And there is Denise—and then I think of you being found some night or some day, dead—will it be in the morning or in the evening—will it be in the summer time or in the autumn?—and Madame and the little one—” Falling into a chair, Toni broke down and cried and sobbed bitterly. Paul put his arm around Toni’s neck. Their two heads were close together just as they had been in the old days on the bridge at Bienville. He said no word to Toni, but the touch of his arm was strength and comfort, and presently Toni stopped crying and grew calm again.

“Never mind, Toni,” said Paul, “I think we can take care of ourselves. We must go armed. It would not do any good if you were to inform on those two rascals. Of course they would deny it—you can’t punish a man for crime he hasn’t committed. We shall have to take our chances—that is all. But if one of us is killed, the other one will be safe, because then your story will be believed.”

That was not much comfort to Toni, who replied:

“If you are killed, what will life be to me? and if I am killed think of Denise, and you.”

They sat a little while longer talking, Paul encouraging Toni and at last raising in him some of the spirit which had made him have Nicolas and Pierre turned out of the railway carriage. Paul said that they were comparatively safe at Beaupré where Nicolas and Pierre would not dare to come, but Toni did not take this view. He thought that men who had committed one murder and had contemplated another for two years would not hesitate to come to Beaupré in order to fulfil their purpose. The effort to keep his agony from being suspected by Denise was, however, perfectly successful. Denise suspected nothing, nor did the sergeant nor anybody, except Paul Verney.