V

THE STRANGE BEHAVIOR OF A CHIMNEY

There was no reason in the world why Hartley Wiggins should not call upon two ladies living in Westchester County, and I must say that he appeared to advantage in Miss Hollister's library.

He had got into his evening clothes somewhere, perhaps at a neighboring inn, or maybe at the house of a friend; for he could not possibly have motored into town and back since his interview with Cecilia in the highway. He had impressed the clerk at the Hare and Tortoise with the idea that he had left New York for a long absence, and he had apparently camped at the gates of Hopefield to be near Cecilia.

When he had paid his compliments to the ladies, he turned to me with an almost imperceptible lifting of the brows; but he was cordial enough. If he was surprised or disappointed at seeing me, his manner did not betray the feeling.

"Glad to see you, Ames. Rather nice weather, this."

"Even Dakota could n't do better," I affirmed with a grin; but he ignored the fling.

"It is quite remarkable, Mr. Wiggins, that you should have appeared just when you did, for we had been speaking of you, and I had been telling Mr. Ames of our travels abroad and in particular of the thumping you very properly gave our courier at Cologne. And I shall not deny that I mentioned also our brief discussion of the peach-crop at Fontainebleau."

Cecilia stirred restlessly; Wiggins shot a glance of inquiry in my direction; and I felt decidedly ill at ease. Miss Hollister crossed to the fireplace and poked the logs.

Just what part Hezekiah Hollister played in the situation was beyond me. If I had not witnessed Wiggins's clandestine meeting with Cecilia, matters would have been clearer to my comprehension; but his appearance at the house, after the colloquy I had overheard from the briar patch, was in itself inexplicable. Cecilia was a woman, therefore to be wooed, and yet she had indicated by her words to him that the wooing, independently of her feeling and inclination, might not go forward with entire freedom. Miss Hollister's singular references to Hezekiah—a person about whom my curiosity was now a good deal aroused—added to the mystery that enfolded the library.

"Our American peaches are not what they were in my youth. Cold storage destroys the flavor. I have not tasted a decent peach for twenty years."

This was pretty tame, I admit; but I felt that I must say something. Responsive to Miss Hollister's energetic prodding, the flames in the fireplace leaped into the great throat of the chimney with a roar. She turned, her back to the blaze, and looked upon her guests benignantly.

"If all your flues draw like that one, they are not seriously in need of doctoring," I remarked, feeling that flues were a safer topic than the peach-crop.

"Flues are nothing if not erratic," replied Miss Hollister. The subject did not appear to interest her; nor had she, by the remotest suggestion, referred to the object of my coming. I had sniffed vainly in the halls above and below for any trace of the stale smoke which usually greeted me at once on my arrival at the house of a client. The air of Hopefield Manor was as sweet as that of a June meadow. Wiggins remarked to me that I doubtless knew the Manor had been designed by Pepperton, whom we both knew well.

"This is Pep's masterpiece. He need do nothing better to keep his grip at the top," he said.

"I consider it a great privilege to be permitted to visit a house designed by a dear friend and occupied by a lady peculiarly fitted to appreciate and adorn it."

I thought rather well of this as I spoke the words; but neither Cecilia nor Wiggins rose to it as I hoped they might.

"You have a neat turn for the direct compliment," said Miss Hollister promptly. "The house was built, you may not know, for a manufacturer of umbrellas, who died before he had occupied it, in circumstances I may later disclose to you; which accounts, Mr. Ames, for that figure of Cupid under a pink parasol on the drawing-room ceiling. At the first opportunity I shall remove it, as baby Cupids are irreconcilable with the militant love-making I admire. I consider umbrellas detestable, and never carry one when I can command a mackintosh."

"When I 'm on the ranch I wear a slicker," said Wiggins. "It's bullet-proof, and that I have found at times a decided advantage."

We discussed mackintoshes for at least ten minutes, with far more sprightliness than I had imagined the subject could evoke. Then Miss Hollister, after a turn up and down the room, paused beside me.

"Mr. Ames," she said, "would you care to join me in a game of billiards? I 'm not in my best form, but I think we might profitably knock the balls for half an hour."

I acquiesced with alacrity. I assumed it to be Miss Hollister's purpose to leave Cecilia and Wiggins alone. I should be rendering Wiggins and Cecilia a service by withdrawing, and I was glad of a chance to escape.

To my infinite surprise they both protested, not in mere polite murmurs but with considerable vehemence.

"It's quite cool to-night, and I don't believe you ought to use the billiard-room until the plumber has fixed the radiator," said Cecilia.

"And if you knew Mr. Ames's game I 'm sure you would n't care to waste time on him," piped Wiggins, whom I had frequently vanquished in billiard bouts at the Hare and Tortoise, where, I may say modestly, I had long been considered one of the most formidable of the club's players.

Both he and Cecilia had risen, and we stood, I remember, just before the hearth, during this exchange. At this moment, a singular thing happened. The fire that had been sweeping in a broad wave-like curve into the chimney was checked suddenly. I had repeatedly marked the admirable draught, the facile grace of the flame as it rose and vanished. The cessation of the draught was unmarked by any of those premonitory symptoms by which a fire usually gives warning of evil intentions. The upward current of air had ceased utterly and without apparent cause. We were all aware of a choking, a gasping in the deep flue, which could not be accounted for by any natural stoppage incident to chimneys—the dislodging of masonry, or a packing of soot. The former was hardly possible and the house was not old enough to make the latter theory plausible. From my survey of the flue on my arrival in the afternoon, I judged that this particular chimney had been little used.

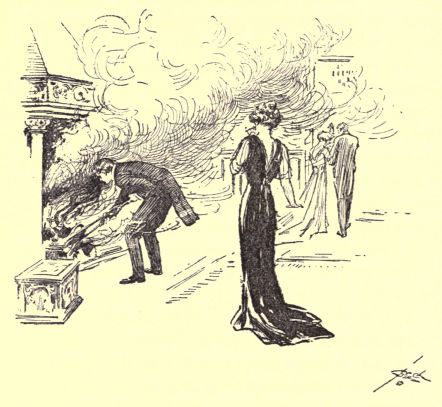

The smoke now rolled out in billows and drove us back from the hearth. I seized the tongs and poker and began readjusting the logs, without, however, any hope of correcting a difficulty that lay patently in the upper regions of the flue itself. The smoke, after a courageous effort to rise, encountered an obstruction of some sort and ebbed back upon the hearth and out into the room. My efforts to stop the trouble by shifting the logs were futile, as I expected them to be, and I retreated quickly, making, I fear, no very gallant appearance as I mopped my face and eyes.

I seized the tongs and poker and began readjusting the logs.

"Well," exclaimed Miss Hollister, who had rung for a servant to open the doors and windows, "this is certainly most extraordinary. What solution do you offer, Mr. Ames?"

"The matter requires investigation. I can't venture an opinion until I have made a thorough investigation. The night is perfectly quiet and the wind is hardly responsible. I think we had better abandon the room until I can solve this riddle in the morning."

The prompt opening of the windows and doors caused the slow dispersion of the smoke, but the lights in the room still shone dimly as through a fog.

"It's beastly," ejaculated Wiggins, coughing. "I did n't suppose Pepperton would put a flue like that into a house. He ought to be shot."

"It is fortunate," said Miss Hollister, "that Mr. Ames is on the ground. He now has a case that will test his most acute powers of diagnosis."

The logs that had burned so brightly before the chimney choked still held their flames stubbornly, and I had advised against pouring water upon them, fearing to crack the brick and stonework. We were about to adjourn to the drawing-room; Miss Hollister and the others had in fact reached the door, leaving me alone before the hearth. Then, as I stood half-blinded watching the smoke pour out into the room, and more puzzled than I had ever been before in any of my employments, the chimney, with a deep intake of breath, began drawing the smoke upward again; the flames caught and spread with renewed ardor; and when the trio still loitering in the hall returned in answer to my exclamation of surprise, the flue had recovered its composure and was behaving in a sane and normal manner.

There is, I imagine, nothing pertaining to the life of man (unless it be rival climates, motor-cars or pianos) that so inspires incompetent, irrelevant and immaterial criticism as wayward fireplaces. It is part of my business to listen respectfully to opinions, to receive with an appearance of credulity the theories of others; and those advanced in Miss Hollister's library were not below the average to which I was accustomed.

"A swallow undoubtedly fell into the chimney-pot and then got itself out again," suggested Cecilia.

"The logs must have been wet. The sap had n't dried out yet," proposed Wiggins.

"The wood was as dry as tinder," averred Miss Hollister, not without irritation. "And one swallow does not make a summer or a chimney smoke. It must have been a changing current of air. I was reading a book on ballooning the other day, and it is remarkable how the air currents change."

"That is quite possible, as the air cools rapidly after sunset at this season, and that is bound to have an effect on the quality and resistance of the atmosphere," I replied sagely.

"Perhaps," suggested Miss Hollister, with one of those flashes of animation that were so delightful in her, "perhaps it was a ghost! Will you tell us, Mr. Ames, whether in your experience you have ever known a chimney ghost?"

As I had no opinion of my own as to what had caused the chimney's brief aberration, I was glad to follow Miss Hollister's lead.

"I have had several experiences with ghosts," I began, "though I should not like you to think that I profess any special genius for the analysis of psychical phenomena. But there was a house at Shinnecock that was reputed to be haunted. The living-room chimney behaved damnably. The house was one of Buffington's. Buffington, you know, was quite capable of building a house and omitting any stairway. We used to say at the club that he ought to have specialized in fire-engine houses, where the men don't use stairways but slide down a pole. Well, the living-room chimney in this particular house could n't be made to draw with a team of elephants, and it had also the reputation of being haunted. Strange flutings of the weirdest and most distressing kind were often heard at night. The owner gave up in despair and moved out, turning the house over to me. After eliminating all other possibilities, I decided that the piping spook must be related to the disorder in the chimney. It served two fireplaces, and I proceeded to knock the kinks out of it so it did n't tie knots in a plumb-line as at first; but, believe me, when it stopped smoking it still whistled, in the most fantastical fashion. I was living in the house, with only the servants about, and for a week gave my whole thought to this flue. The ghostly flutist was an amateur, but he tried his hand at every sort of tune, from 'Sally in our Alley' to the jewel song in Faust. The whistling did n't begin till nearly midnight, and continued usually for about an hour. I tried in every way to lure him into the open, and I fell downstairs one night as I crept about in the dark trying to trace the sound. And to what palpable and mundane source do you suppose I traced that ghost?"

"I never should guess," murmured Cecilia, "unless it was merely the weird whistling of the wind."

"Nothing so poetical, I'm sorry to confess. It was the butler! In his nightly cups his soul inclined to music, and being a timid soul, fearful of the cynical tongues of the other servants, he crawled into the ash-dump in the cellar, which communicated with the several fireplaces above, and there indulged himself gently upon the tuneful reed. The night I caught him he was breathing the wild strains of Brunhilde's Battle-Cry into the tube, and it was shuddersome, I can tell you! I took it upon myself to discharge him on the spot, and the grateful owner returned the next day."

"The presence of a ghost in this house would give me the greatest pleasure," declared Miss Hollister, who had listened intently to my recital. "I should look upon a ghost's appearance at Hopefield Manor as a great compliment. If any reputable, decent ghost should by any chance take up his residence in this house, I should give him every encouragement."

Miss Hollister seemed to have forgotten the proposed game of billiards. The chimney's lawless demonstration had, in fact, given a new turn to the evening. We discussed ghosts for half an hour, and then, without having enjoyed any opportunity for a single private word with Cecilia, Wiggins rose to leave. He shook hands all around and bowed from the door. It was in my mind to follow, making a pretext of walking with him to the station or of helping him find his car; but nothing in his good-night to me encouraged such attentions, and as I pondered, the outer door closed upon my irresolution.

At the stroke of ten Miss Hollister rose and excused herself. "We breakfast at eight, Mr. Ames. I trust the hour does not conflict with your habits."

I assured her that the hour was wholly agreeable, and she gave me her hand with great dignity.

When I turned toward Cecilia she had moved to a seat close by the hearth and was gazing dreamily into the fire, now a bed of glowing coals.

"It was odd," I remarked.

"You mean the chimney?"

"Yes. It was quite unaccountable. I confess that I never knew a chimney's mood to change so abruptly."

She sat silent for several minutes, and then she lifted her head and her eyes met mine.

"Pardon me, Mr. Ames, but did my aunt ask you here to examine the chimneys? I did n't quite understand. We have been here only a week; the weather has been warm, and I believe this fire had not been lighted before to-day. You will pardon my frankness, but I can't quite understand why my aunt invited you here if you came professionally. I thought when you appeared this afternoon that you were a guest—nothing more—or less."

"You had heard nothing of any trouble with the fireplaces? Then I am in the dark as much as you. As I understood it, I was called here to examine the flues; but now that I think of it, she did not say explicitly that her chimneys were behaving badly, though that was of course implied. I naturally assumed that she summoned me here in my professional capacity. I was a stranger to your aunt; she would hardly have invited me otherwise."

She turned again to the fire as though referring to it for counsel. Her perplexity was no greater than my own. It was certainly an extraordinary experience to be invited to a strange house where my services had not been needed, and to find that an apparently sound chimney had begun to smoke at once as though in mockery of my presence.

"I imagine, however, that your aunt acts a good deal on impulse. Her asking me here may have been only a whim."

"Please don't imagine that your coming has not been agreeable to me," Cecilia protested. "My aunt is quite capable of inviting a stranger to the house. She met you, I believe, at the Asolando. I hope you understand that it is only because I am in deep trouble, Mr. Ames, trouble of the gravest nature, that I have ventured to speak to you in this way of my aunt, for whom I have all respect and affection."

She had never, I was sure, been lovelier than at this moment. Her eyes filled, but she lifted her head proudly. Whatever the trouble might be I was sorry for it on her own account; and if it involved Hartley Wiggins my sympathy went out to him also. On an impulse I spoke of him.

"I was surprised to meet Hartley Wiggins here. He 's a dear friend of mine, you know. I thought he had gone to his ranch. He left the Hare and Tortoise very abruptly a few nights ago just after we had dined together. He must be stopping somewhere in the neighborhood."

"It's quite possible. And there's an inn, you know. I fancy he drove over from there."

"I hadn't thought of that; the Prescott Arms, I suppose you mean."

She nodded, but she was clearly not interested in me, and when I found myself failing dismally to divert her thoughts to cheerfuller channels, I rose and bade her good-night.

The servant who had previously attended me appeared promptly when I reached my room, bearing a tray, with biscuits and a bottle of ale. He gave me an envelope addressed in a hand I already knew as Miss Octavia's, and I opened and read:—

"The following I either detest or distrust, so kindly refrain from mentioning them while you are a guest of Hopefield Manor:—

Automobiles.

Mashed Potatoes.

Whiskers.

Chopin's Concerto in E Minor (op. 11).

Bishop's Coadjutor.

Limericks.

Cats.

OCTAVIA HOLLISTER."

I absorbed this with a glass of ale. There were seven items, I noted, and I had no serious quarrel with her attitude toward any of them; but just what these matters had to do with me or my presence in her house I could not determine. She had referred to me in the note as a guest—I had noted that; and I did know, moreover, that Miss Octavia Hollister possessed a quaint and delicate humor; and I looked forward with the pleasantest anticipations to our further meetings.

Before I slept I threw up my window and stepped out upon a narrow balcony that afforded a capital view of the fields and woods to the east. The night was fine, with the sky bright with stars and moon. As my eyes dropped from the horizon to the near landscape, I saw a man perched on a knoll in the midst of a corn-field. He stood as rigid as a sentry on duty, or like a forlorn commander, counting the spears of his tattered battalions. I was not sure that he saw me, for the balcony was slightly shadowed, but at any rate, he was sharply outlined to my vision. His derby hat and overcoat gave him an odd appearance as he stood brooding above the corn. Then he vanished suddenly, though, as he retired toward the highway, I followed him for some time by the shaking and jerking of the corn-stalks.

I lay awake far into the night, considering the events of the day. Of these the curious stoppage of the library chimney was the least interesting. I doubted whether it would ever recur. The love-affair of Hartley Wiggins was, however, a matter of importance to me, his friend, and I determined to make every effort to see him the next day and learn the exact status of his affair with Cecilia Hollister.