VII

NINE SILK HATS CROSS A STILE

A girl in a white sweater sat on a stone wall and munched a red apple; but this is to anticipate.

I had made a wrong turn on leaving the Prescott Arms, and I came out presently near Katonah village. I got my bearings of a shopkeeper and started again for Hopefield Manor; but the mid-afternoon was warm, and the hills were steep, and as Miss Hollister's admirable cob showed signs of weariness, I drove into a fence-corner and loosened the mare's check. On a sunny slope several hundred yards above the highway lay an orchard, advertised to the larcenous eye by the ruddiest of red apples. Not in many years had I robbed an orchard, and I felt irresistibly drawn toward the gnarled trees, which were still, in their old age, abundantly fruitful.

When I reached the orchard I found it quite isolated, with only fallow fields, seamed with stone fences, stretching on either hand. A spring near by sent the slenderest of brooks flashing down the slope. There was no house in sight anywhere, and the neglected orchard flaunted its bright fruit with pathetic bravado. I drew down a bough and plucked my first apple, tasted, and found it good. At my palate's first responsive titillation, something whizzed past my ear, and following the flight of the missile, I saw an apple of goodly size fall and roll away into the grass. I had imagined myself utterly alone, and even now, as I looked guiltily around, no one was in sight. The apple had passed my ear swiftly and at an angle quite un-Newtonian. It had been fairly aimed at my head, and the law of gravitation did not account for it. As I continued my scrutiny of the landscape, I was addressed by a voice whose accents were not objurgatory. Rather, the tone was good-natured and indulgent, if not indeed a trifle patronizing. The words were these:—

"Soup of the evening, beautiful soup!"

It was then that, lifting my eyes, I beheld, sitting lengthwise of the wall, with her feet drawn comfortably under her, a girl in a white sweater, bareheaded, munching an apple. There was no question of identity: it was the girl whose head behind the cashier's grill of the Asolando had interested me on the occasion of my second visit to the tea-room. In soliciting my attention by reciting a line of verse, she had merely followed the rule of the tea-room in like circumstances. The casting of the apple at my head possessed the virtue of novelty, but now that her shot was fired and her line spoken, she addressed herself again to her apple. Her manner implied indifference; but her unconcern was that of a trout not wishing to discourage the fisherman, feigning a languid interest in a familiar fly dropped at its nose. While I tried to think of something to say, I pecked at my own apple, but kept an eye on her. She concluded her repast calmly and flung away the core.

"I mentioned soup," she remarked. "The courses are mixed. We have partaken of fruit. Are you fish, flesh, fowl, or good red herring?"

"Daughter of Eve, I will be anything you like. I 'm obliged for the apple, and I apologize for having entered Eden uninvited."

"It's not my Eden. Nobody invited me. But it's not too much to say that these apples are grand."

"I 'm glad we 're both in the same boat. I 'm a trespasser myself. I don't even know the name of the owner. But if you have had only one apple, two more are coming to you, if you follow Atalanta's precedent."

"I don't follow precedents, and I 've forgotten the name of the boy who threw the apples in the race. It does n't matter, though; nothing matters very much."

Her hands clasped her knees. Her skirt was short, and I was conscious that she wore tan shoes. She continued to regard me with lazy curiosity. She seemed younger than at the Asolando. Not more than eighteen times had apples reddened on the bough in her lifetime! She was even slenderer and more youthful in her sweater than in the snowy vestments of the Asolando. Her hair which, in the glow of the lamp at Asolando cash-desk had been golden, was to-day burnished copper, and was brushed straight back from her forehead and tied with a black ribbon.

"I quite agree with your philosophy. Nothing is of great importance."

"So it's not your orchard?" she asked.

"The thought flatters me. I own no lands nor ships at sea. I 'm a chimney doctor, and if necessary I 'll apologize for it."

"You needn't submit testimonials; I take the swallows out of my own chimneys."

"That requires a deft hand, and I 'm sure you 're considerate of the swallows."

"You may come up here and sit on the wall if you care to. I saw you driving in a trap. I hope your horse is n't afraid of motors; motors speed scandalously on that road."

"I am not in the least worried about my horse. It's borrowed. As you remarked, this is a nice orchard. I like it here."

"If you are going to be silly, you will find me little inclined to nonsense."

"Shall we talk of the Asolando? I haven't been back since I saw you there. And yet,—let me see, is n't this your day there?"

She seemed greatly amused; and her laughter rose with a fountain-like spontaneity, and fell, a splash of musical sound, on the mellow air of the orchard. She had changed her position as I joined her, sitting erect, and kicking her heels lazily against the wall.

"Mr. Chimney Man, something terrible happened just after you left that afternoon. I was bounced, fired; I lost my job."

"Incredible! I 'm sure it was not for any good cause. I can testify that you were a model of attention; you were surpassingly discreet. You repelled me in the most delicate manner when I intimated that I should come often on the days that you made the change."

"The sad part of it was that that was not only my last day but my first! I had never been there before, except for a nibble now and then when I was in town. But I could n't stand it. It was like being in jail; in fact, I think jail would be preferable. But I 'm glad I spent that one day there. It proved what I have long believed, that I am a barbarian. That poetry on the walls of the Asolando made me tired, not that it is n't good poetry, but that the walls of a tea-shop are no place for it. I always suspect that people who like their poetry framed, and who have uplift mottoes stuck in mirrors where they can study them while they brush their hair in the morning, never really get any poetry inside of them. You need a place like this for poetry,—an old orchard, with blue sky and a crumbly wall to sit on. I tried the Asolando as a lark, really, not because I 'm deeply entertained by that sort of thing. They dispensed with my company because I remarked to one of the silly girls who are making the Asolando their life-work that I thought the English Pre-Raphaelites had carried the dish-face rather too far. The girl to whom I uttered this heresy was so shocked she dropped a tea-cup,—you know how brittle everything is in there,—and I came home. You were really the only adventure I got out of my day there. And I did n't find you entirely satisfactory."

"Thank you, Francesca, for these confidences. And having lost your position you are now free to roam the hills and dream on orchard walls. Your scheme of life is to my liking. I can see with half an eye that you were born for the open, and that the walls of no prison-house can ever hold you again."

She nodded a dreamy acquiescence. Then she turned two very brown eyes full upon me and demanded:—

"What is your name, please?"

I mentioned it.

"And you doctor chimneys? That sounds very amusing."

"I 'm glad you like it. Most people think it absurd."

"What are you doing here? There's not a chimney in sight."

"Oh, I have a commission in the neighborhood. Hopefield Manor; you may have heard of Miss Hollister's place."

"Of course; every one knows of her."

"And now that I think of it, it was she about whom you asked in the Asolando that afternoon. You wanted to know what she said about the tea-room."

"I remember perfectly."

She was quiet for a moment, then she threw back her head and laughed that rare laugh of hers.

"You might let me into the joke."

"It would n't mean anything to you. I have a lot of private jokes that are for my own consumption."

"Your way of laughing is adorable. I hope to hear more of it. In the Asolando you repulsed me in a manner that won my admiration, but I venture to say now that, if you roam these pastures, I am the grass beneath your feet; and if yonder tuneful water be sacred to you, I sit beside the brook to learn its song."

"You talk well, sir, but from your tone I fear you can't forget that we met first in the Asolando. That day of my life is past, and I am by no means what you might call an Asolandad. I don't seem to impress you with that fact. I 'm a human being, not to be picked like a red apple, or trampled upon like grass, or listened to as though I were a foolish little brook. I 'm greatly given to the highway, and I prefer macadam. I like asphalt pavements, too, for the matter of that. I should love a motor, but lacking the coin I pedal a bicycle. My wheel lies down there in the bushes. You see, Mr. Chimney Man, I am a plain-spoken person and have no intention of deceiving you. My name was Francesca for one day only. It may interest you to know that my real name is Hezekiah."

"Hezekiah!"

I must have shouted it; she seemed startled by my violence.

"You have pronounced it correctly," she remarked.

"Then you are Cecilia's sister and Miss Hollister's niece."

"Guilty."

"And you live?"—

"Over there somewhere, beyond that ridge," and she waved her hand vaguely toward the village and laughed again.

"Pray tell me what this particular joke is: it must be immensely funny," I urged, struggling with these new facts.

"Oh, it's Aunt Octavia! She will be the death of me yet! You know the girl who waited on Aunt Octavia that afternoon took all that artistic nonsense as seriously as a funeral, and she told me after you left, with the greatest horror, that Aunt Octavia had asked for a cocktail!" That laugh rippled off again to carry joy along the planet-trails above us. "But you know," she resumed, "that Aunt Octavia never drank a cocktail in her life,—and would n't! She does n't know a cocktail from soothing syrup! She pines for adventures. She is just like a boarding-school girl who has read her first romance of the young American engineer in a South American republic, shooting the insurgents full of tortillas and marrying the president's dark-eyed daughter. She reads pirate books and is crazy about buried chests and pieces of eight. And they say I 'm just like her! She is the most perfectly killing person in the world!"

Hezekiah laughed again.

So this was the child whose devotion had rendered Wiggins so miserable, and the sister of whom Cecilia Hollister and her aunt had spoken so strangely. I had not suspected it. She was as unlike Cecilia as possible, and the difference lay in her independent spirit and bubbling humor. Her individuality was more pronounced. You took her, without debate, on her own ground; and though she had expressed a preference for macadam, she seemed related to the days when maidens sat on sunny walls and were not disappointed in their expectation that light-footed youths, or mayhap winged sons of the Olympians, would reward patient waiting. But at the same time she struck the note of modernity. Her flings at the Asolando were reassuring; she was a healthy-minded, vigorous young woman whose nature protested against affectation and pose. She rebelled against closed doors, whether those of town or country. I am myself much of a cockney, and not averse to asphalt and streets ablaze with electric banners. My imagination sprang to meet this Hezekiah. I had, in fact, a feeling that I had waited for her somewhere in some earlier incarnation. She jumped down from the wall, shook three apples from a tree, and sustained them in the air with the deftness and certainty of practised jonglerie. Her absorption was complete, and when she wearied of this sport, she flung the apples away, one after the other, with a boy's free swing of the arm. Herrick would have delighted in her; Dobson would have spun her bright hair into a rondeau; but only Aldrich, with a twinkle in his eye, could have brought her up to date in a dozen chiming couplets. I felt that no matter how much one admired and respected this Hezekiah one would never deal with her in the phrases of drawing-rooms. Her charming inadvertences made this impossible; and it was the part of discretion to await her own initiative.

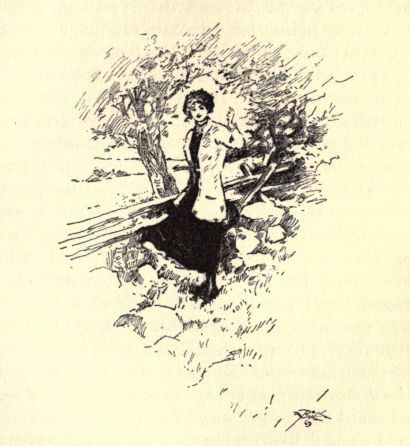

She had gone on up to the crest of the orchard, and stood clearly limned against the sky, her hands thrust into the pockets of her sweater. She appeared to be intent upon something that lay beyond, and half turned her head and summoned me by whistling. I liked this better than the quotation method of address. It was a clear shrill pipe, that whistle, and she emphasized it further by a peremptory wave of her arm. When I stood beside her I was surprised to find that the site commanded a wide area, including the unmistakable roofs and chimneys of Hopefield Manor half a mile distant.

She emphasized it further by a peremptory wave of her arm.

"You will see something funny down there in a minute. They are out of sight now, but there 's a stile—the kind with steps, just beyond those trees. It's in a path that leads from the Prescott Arms to Aunt Octavia's. Look!"

My eyes discovered the stile. It was set in a wall that was, she told me, the boundary dividing Hopefield Manor from another estate nearer our position.

Suddenly a silk hat bobbed in the path beyond the stile; it rose as its owner mounted the steps; it paused an instant when the top of the stile was reached; then quickly descended, and came toward us, a black blot above a black coat. I was about to ask her the meaning of this apparition when a second silk hat bobbed in the path and then rose like its predecessor, descending and keeping on its way until hidden from our sight by shrubbery. A third, fourth, fifth, sixth, seventh, eighth, and ninth followed. Nine gentlemen in silk hats crossing a stile in a lonely pasture between woodlands; so much was plain to the eye from our vantage-ground; but I groped blindly for an explanation of this spectacle. The bobbing hats and dark coats suggested wanderers from some dark Plutonian cave, bent upon mischief to the upper world. Their step was jaunty; they moved as though drilled to the same cadence.

We waited a moment, expecting that another figure might join the strange procession, but nine was the correct count. I looked down to find Hezekiah checking them off on the fingers of her slim brown hand.

"Has there been a funeral and are they the returning pall-bearers?" I inquired.

"Not yet," she replied.

Her face showed amusement; the twitching of her lips encouraged hope that another of those delightful laughs was imminent.

"It was positively weird," I said. "It reminds me of a dream I used to have, when I was a boy, of a long line of Chinamen running along the top of a great wall,—an interminable procession. I must have dreamed that dream a hundred times. I could hear the pigtails of those fellows flapping against their backs as they trotted along, and the soft scraping of their sandals on the smooth surface of the wall. But the pot hats are equally eerie and unaccountable to my dull twentieth-century senses. Pray tell me the answer, Hezekiah."

"Oh, those are Cecilia's suitors. They've been to Aunt Octavia's to tea. They 're staying at the Prescott Arms probably."

"They 're terribly formal. I can't get rid of the impression of sombreness created by those fellows. You 'd hardly expect them to tramp cross country in those duds. Such grandeur should go on wheels."

"Oh, they are afraid of Aunt Octavia! She won't allow a motor on her grounds; and I suppose they 're afraid they might break some other rule if they went on any kind of wheels. She 's rather exacting, you know, my aunt Octavia."

"I was at the Prescott for luncheon to-day, and I must have seen these gentlemen there."

"Oh, you were at the Prescott?"

Almost for the first time her manner betrayed surprise; but mischief danced in the brown eyes. With Wiggins's confession as to the havoc he had played with Hezekiah's confiding heart fresh in my memory, I felt a delicacy about telling her that it was to see Wiggins that I had visited the inn. But to my surprise she introduced the subject of Wiggins immediately, and with laughter struggling for one of those fountain-like splashes that were so beguiling.

"Oh, Wiggy is staying there! Do you know Wiggy?"

"Know Wiggy, Hezekiah? I know no man better."

"Wiggy is no end of fun, isn't he? I've heard him speak of you. You are his friend the Chimney Man. He was the last man over the stile. Did you notice that he lingered a moment longer at the top than the others? From his being the ninth man I imagine that he was the last to leave the house, and he probably felt that this set him apart from the others. Wiggy is nothing if not shy and retiring."

A heart-broken, love-lorn girl did not speak here. She whistled softly to herself as we descended. The air was cooling rapidly, and the west was hung in scarlet and purple and gold. The horse neighed in the road below, and I knew that I must be on my way to the Manor.

"Hezekiah," I said, when I had drawn her bicycle from its hiding-place, "you 'd better leave your wheel here and let me drive you home. It's late and there 's frost in the air. I imagine it's some distance to your house."

"Thank you, Mr. Chimney Man; but it is much farther to Aunt Octavia's, for you have to make a long circuit around the hills. And besides, as we met in the orchard, it would be altogether too commonplace a conclusion of our adventure for you to drive me home behind a mere horse. But tell me this: what do you think of Wiggy's chances?"

"Of winning your sister? I should say from my knowledge of Wiggins that he is a man much given to staying in a game once the cards are shuffled."

She nodded, standing beside her wheel, her hands on the bars. Her manner was contemplative; her eyes for a moment were deep, shadowless pools of reverie.

"Then you think he knows the game?"

There seemed to be something beneath the surface meaning of her words, but I answered:—

"Wiggy's affairs have been few, and while he may not know the game in all its intricacies, he has a shrewd if rather slow mind, and besides, he has asked my help in the matter."

"One of these speak-for-yourself-John situations, then? Well, I should say, Mr. Chimney Man, I should say"—

She made ready for flight, looking ahead to be sure of a clear thoroughfare.

"I should say," she concluded, settling her skirts, "that that indicates considerable intelligence on Wiggy's part."

The tires rolled smoothly away; the gravel crunching, the pebbles popping. The white sweater clasped a straight back snugly; then suddenly, as the wheels gained momentum, she bent low for a spurt, and her rapidly receding figure became a gray blur in the purple dusk.