X

MY BEFUDDLEMENT INCREASES

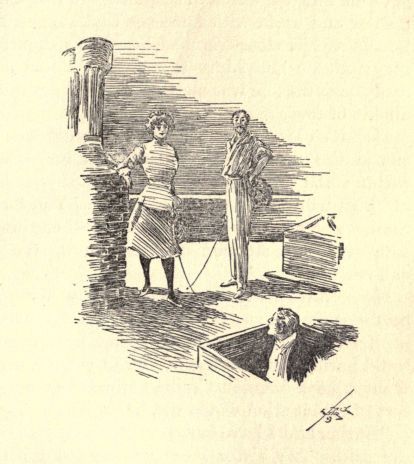

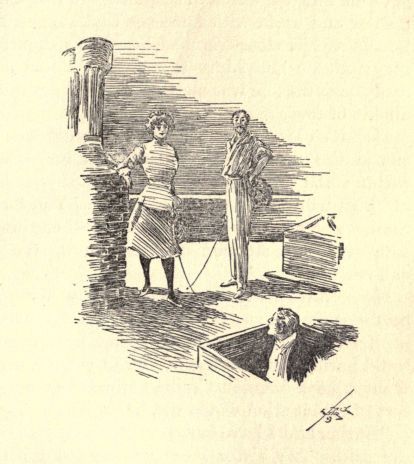

I had been surprised to find the hatch open, but it is not too much to say that I was greatly astonished by what I saw on the moon-flooded roof. There, midway of a flat area that lay between the two larger chimney-pots, two persons were intently engaged, not in ghostly promenading or posturing, or even in audible conversation, but in a spirited bout with foils! The clicking and scraping of the steel testified unmistakably to the reality of their presence. And I was grateful for those sounds! It needed only silence to tumble me back down the trap with chattering teeth, but these were beyond question corporeal beings, albeit rendered weird and fantastical by the oddity of their playground and the soft effulgence of the moon. The vigor of the onset and the skill of the antagonists held me spellbound. I stood with head and shoulders thrust through the opening, staring at this unusual spectacle, and not sure but that after all my eyes were tricking me.

"Touché!"

It was a woman's voice, faint from breathlessness. She threw off her mask and dropped her foil, and with a most human and feminine gesture put up her hands to adjust her hair. It was Cecilia Hollister, in a short skirt and fencing coat!

Her opponent was a man, and as he too flung off his mask I saw that he was a gentleman of years. If Miss Cecilia Hollister chose to meet strange men on the roof of her aunt's house and practice the fencer's art with them, it was no affair of mine, and I was about to withdraw when the stranger swung round and saw me. His sudden exclamation caused the girl to turn, and as a reasonable frankness has always seemed to me essential to a nice discretion, I crawled out on the roof.

"I beg your pardon, Miss Hollister, but if I had known you were here I should not have intruded. The vagaries of the library chimney have been on my mind, and I was about to have another peep into yonder pot."

She stood at her ease, with one hand resting lightly against the inexplicable chimney in question, and still somewhat spent from her exercise.

She stood at her ease, with one hand resting lightly

against the inexplicable chimney.

"Father," she said, turning to the stranger who stood near, "this is Mr. Ames, who is Aunt Octavia's guest."

The light of the gibbous moon enabled me to discern pretty clearly the form and features of Mr. Bassford Hollister. And I find, in looking over my notes, that I accepted as a matter of course the singular meeting with my hostess's brother. I had grown so used to the ways of the Hollisters I already knew, that the meeting with another member of the family at eleven o'clock at night on the roof of this remarkable house gave me no great shock of surprise. He was tall, slender and dark, with fine eyes that suggested Cecilia's. His close-trimmed beard was slightly gray: but he bore himself erect, and I had already seen that he was alert of arm and eye and nimble of foot.

He put on his coat, which had been lying across one of the crenelations, and covered his head with a small soft hat.

"This will do for to-night, Cecilia. You had the best of me. We 'll try again another time. I 'm glad you stopped us, Mr. Ames. We 'd had enough."

He seemed in no wise disturbed by my appearance, nor in any haste to leave. This meeting between the father and daughter, I reasoned, could hardly have been a matter of chance, and it must have been in Cecilia's mind that some sort of explanation would not be amiss.

"Father and I have fenced together for years," she said. "My sister Hezekiah does not care for the sport. As you have already seen that my aunt Octavia is an unusual woman, given to many whims, I will not deny to you that at present my father is persona non grata in this house. I beg to assure you that nothing to his discredit or mine has contributed to that situation, nor can our meeting here to-night be construed as detrimental to him or to me. In meeting my father in this way I have in a sense broken faith with my aunt Octavia, but I assure you, Mr. Ames, that it is only the natural affection for a daughter that led my father to seek me here in this clandestine fashion."

Cecilia had spoken steadily, but her voice broke as she concluded, and she walked quickly toward the hatchway. Her father stepped before me to give her his hand through the opening.

I withdrew to the edge of the roof while a few words passed between them that seemed to be on his part an expostulation and on hers an earnest denial and plea. He passed her the foils and masks and she vanished; whereupon he addressed himself to me.

"I had learned from both my daughters of your presence in my sister's house, and I had expected to meet you, sooner or later. This is a strange business, a strange business."

He had drawn out a pipe, which he filled and lighted dexterously. The flame of his match gave me better acquaintance with his face. He leaned against the serrated roof-guard with the greatest composure, his hat tilted to one side, and drew his pipe to a glow. I had not forgotten my encounter with the ghost on the stair, and as I waited for him to speak, I was trying to identify him with the mysterious agency that had tampered with the lights, and passed so ghostly a hand across my face in the stair-well. I could hardly say that there had not been time for either Bassford Hollister or his daughter to have reached the roof after my experiences on the stair; and yet they had been engaged so earnestly at the moment of my appearance at the hatchway that it was improbable that either could have played ghost and flown to the roof before I reached it. And eliminating the ghost altogether, I had yet to learn how Bassford Hollister had gained entrance to the house. It seemed best to drop speculations and wait for him to declare himself.

"You must understand, Mr. Ames, that my daughters, both of them, are very dear to me. It is the great grief of my life that owing to matters beyond my control I have been unable to care for them as I should like to do. This being the case, I have been obliged to allow them to accept many favors from my only sister Octavia. This in ordinary circumstances would not be repugnant to my pride; but my sister is a very unusual person. She must do for my children in her own way, and while I was prepared, in agreeing that they should accept her bounty, for some whimsical manifestation of her eccentric character, I did not imagine that she would go so far as to shut me out from all knowledge of her plans for them. That, Mr. Ames, is what has happened."

His voice rose and fell mournfully. He puffed his pipe for a moment and continued:—

"Cecilia, being the older, was to be launched first. Hezekiah was to be cared for in due season. Last summer Octavia took them both abroad. As you are aware, they are young women of unusual distinction of appearance and manner, and they attracted a great deal of attention. From what I hear, a troop of suitors followed them about. That sort of thing would appeal to Octavia; to me it is most repellent, but I had already committed myself, agreeing that Octavia should manage in her own fashion. There is now something forward here which I do not understand. I have an idea that Octavia has contrived some preposterous scheme for choosing a husband for Cecilia that is in keeping with her odd fashion of transacting all her business. I do not know its nature, and by the terms of her agreement Cecilia is not to disclose the method to be employed to me,—not even to me, her own father. You must agree, Ames, that that is rather rubbing it in."

"But you don't assume that your daughter is not to be a free agent in the matter? You don't believe that some unworthy and improper man is to be forced upon her?"

"That, sir, is exactly what I fear!"

"You will pardon me, but I cannot for a moment believe that Miss Hollister would risk her niece's happiness even to satisfy her own peculiar humor. Your sister is a shrewd woman, and her heart, I am convinced, is the kindest. Among the suitors now camped at the Prescott Arms there must be some one whom your daughter approves, and I see no reason why he should not ultimately be her choice. Now that you have broached the matter, I make free to say that one of these suitors is an old friend of mine. Hartley Wiggins by name, and that he is a man of the highest character and a gentleman in the strictest sense."

He had been listening to me with the greatest composure, but at the mention of Wiggins's name he started and nervously clutched my arm.

"That man may be all that you say," he cried chokingly, "but he has acted infamously toward both my daughters. He is a rogue, and a most despicable fellow. He has flirted outrageously with Hezekiah while at the same time pretending to be deeply interested in Cecilia. I say to you in all candor that a man who will trifle with the affections of a child like Hezekiah is a villain, nothing less."

"But, my dear sir, is it not possible that you do him a great wrong? May it not be the other way round, that Hezekiah is trifling with Wiggins's affections? He 's a splendid fellow, Hartley Wiggins, but he 's a little slow, that's all. And between two superb young women like your daughters a man may be pardoned for doubts and hesitations; a case of being happy with either if t'other dear charmer were only away. To put it quite concretely, I will say that in my own very slight acquaintance with these young women I feel the spell of both. Your sister, I take it, is anxious not to show partiality for any of these men, and yet I dare say she probably feels kindly disposed toward Wiggins. His worst crime seems to be that he chose Tory ancestors! The thing is bound to straighten itself out."

He tossed his head impatiently.

"Has it occurred to you that Octavia's interest in this Hartley Wiggins may be due to a trifling and immaterial fact?"

"Nothing beyond his indubitable eligibility."

"Then let me tell you what I suspect. Both his names contain seven letters. My sister is slightly cracked as to the number seven. I swear to you my belief that the fact that his names contain seven letters each is at the bottom of all this. Incredible, my dear sir, but wholly possible!"

"Then, such being the case, why does n't she show her hand openly? If she believes that Wiggins with his septenary names is ordained by the seven original pleiades to marry your daughter Cecilia, I should think that by the same token she would have sought a man rejoicing in the noble name of Septimus. You send conjecture far when once you entertain so absurd an idea."

"You think my assumption unlikely?" he asked eagerly.

"I certainly do, Mr. Hollister. But I confess that I had never counted the letters in Wiggins's name before, and your suggestion is interesting. And this whole idea of the potential seven in our affairs has possibilities. If seven at all, why is n't it possible that your sister has Jacob in mind and the seven years he served for Rachel? You may as well assume that, as Wiggins is specially favored in the number of letters in his singularly prosaic and unromantic name, it is Miss Hollister's plan to keep him dallying seven years."

He seized me by the arm and forced me back against the battlements, then stood off and eyed me fiercely.

"You speak of serving and of service! Will you tell me just why you are here and what brings you into this affair! My daughter Hezekiah is the frankest person alive, and she told me of her meetings with you and that you had been to the Asolando,—where she spent a day in the sheerest spirit of mischief. That was the beginning of all our troubles, that damned hole with its insane confectionery and poetry. If Cecilia, in a misguided notion of earning her own living, had not gone there and worn an apron for a week before I dragged her out, she would never have met Wiggins. And now will you kindly tell me just what you are doing in my sister's house, where I have to come like a thief in the night to see one of my own children?"

This fierce deliverance touched me nearly: I doubted my ability to explain to one of these amazing Hollisters just how I came to be sojourning in the house of another of the family without any business that would bear scrutiny. I hastened to declare my profession, and that I had been summoned by Miss Hollister to examine her chimneys. I could not, however, tell him that until my arrival the chimneys had behaved themselves admirably!

"You've admitted your friendship for this Wiggins person; that's enough," he said when I had concluded. "I advise you to leave the house at once. I tell you he 's got to be eliminated from the situation. Understand, that I do not threaten you with violence, but I will not promise to abstain from visiting heavy punishment upon that fellow. And you? A chimney-doctor? I am a man of considerable knowledge of the world, and I say to you very candidly that I don't believe there is any such profession."

"Then let me tell you," I replied, not without heat, "that I am a graduate in architecture, and that if you will do me the honor to consult a list of the alumni of the Institute of Technology, you will find that I was graduated there not without credit. And as for remaining in this house, I beg to inform you, Mr. Hollister, that as I am your sister's guest and as she is perfectly competent to manage her own affairs, I shall stay here as long as it pleases her to ask me to remain. And now, one other matter. How did you gain this roof to-night, when by your own admission you are not on such terms with your sister as would justify you in entering it openly?"

The moonlight did not fail to convey the contempt in his face, but I thought he grinned as he answered quietly:—

"You don't seem to understand, young man, that you are entitled to no explanations from me. If my sister has her sense of a joke, I assure you that I have mine. I came here to see my daughter. As I taught her to fence when she was ten years old and as she is particularly expert, and moreover, as in my present condition of poverty I have been obliged to forego the pleasure of metropolitan life and to give up my membership in the Fencers' Club, you can hardly deny my right to meet my own daughter for a brief bout anywhere I please. You strike me as a singularly fresh young person. It would be a positive grief to me to feel that my conduct had displeased you. And now, as the night grows chill, I shall beg you to precede me into the house by the way you came."

"But first," I persisted, "let me ask a question. It is possible that you yourself have some preference among your daughter's several suitors, Mr. Hollister. Would you object to telling me which one you would choose for Miss Cecilia?"

"Beyond question, the man for Cecilia, if I have any voice in the matter, is Lord Arrowood."

"Arrowood!" I exclaimed. "You surprise me greatly. I saw him at the inn, and he seemed to me the most insignificant and uninteresting one of the lot."

"That proves you a person of poor gifts of discernment, Mr. Ames;" and his tone and manner were quite reminiscent of his sister's ways; and his further explanation proved him even more worthily the brother of his sister.

"As I was obliged," he began, "owing to an unfortunate physical handicap, to abandon my art, that of a marine painter, I have given my attention for a number of years to the study of the Irish situation. Between the various political parties of Great Britain, poor Ireland can never regain her ancient power. But I see no reason why she should not become once more a free and independent nation. I have gone deeply into Irish history, and I may modestly say that I probably know that history from the time of the Anglo-Norman invasion to the death of Gladstone better than any other living man. I met Arrowood by chance in the highway yesterday, and I found that he holds exactly my ideas."

"But Arrowood isn't an Irishman," I interjected; "neither, I should say, are you!"

"That's not to the point. Neither was Napoleon a Frenchman strictly speaking; nor was Lafayette an American. A friend of mine in Wall Street is ready, when the time is ripe, to finance the scheme by selling bonds to the multitudes of Irish office-holders throughout the United States,—most of whom are not unknown to the banks."

"And I suppose you and Arrowood would sit jointly in the seat of the ancient kings in Dublin after you had effected your coup."

"You lose your bet, Mr. Ames. We have agreed that, as the mayors of Boston for many years have been Irishmen, and as they have, by their prowess in holding the natives in subordination, demonstrated the highest political sagacity, we could not do better than take one of these rulers of the old Puritan capital and place him on the Irish throne. The keen humor of that move would so tickle all interested powers, that the investiture and coronation of the new ruler would be accomplished without firing a shot."

This certainly had the true Hollister touch! Miss Octavia herself could not have devised a more delightful scheme.

"And so," Mr. Bassford Hollister concluded, "I naturally incline toward Arrowood, though he is so poor that he was obliged to come over in the steerage to continue his wooing of my daughter."

He let himself down into the dark trunk-room, waited for me courteously, and walked by my side to the stairway, both of us maintaining silence. I was deeply curious to know how he had entered and whether he expected to go down the front way and out the main door. We kept together to the third-floor hall,—I could have sworn to that; then suddenly, just as we reached the stairway, out went the lights, and we were in utter darkness. I smothered an exclamation, clutched my matches and struck a light, and as the stick flamed slowly, I looked about for Bassford Hollister; but he had vanished as suddenly and completely as though a trap had yawned beneath us and swallowed him. I found the third-floor switch and it responded immediately, flooding the stair-well to the lower hall, but I neither saw nor heard anything more of Hollister.

Astounded by this performance, I continued on to the lower floor to have a look around, and there, calmly reading by the library table, sat Miss Octavia!

"Late hours, Mr. Ames!" she cried. "I supposed you had retired long ago."

I was still the least bit ruffled by that last transaction on the stair, and I demanded a little curtly:—

"Pardon my troubling you; but may I inquire, Miss Hollister, how long you have been sitting here?"

The clock on the stair began to strike twelve, and she listened composedly to a few of the deep-toned strokes before replying.

"Just half an hour. I thought some one knocked at my door about an hour ago. The lights were on and I came down, saw a magazine that had escaped my eye before, and here you find me."

"Some one knocked at your door?"

"I thought so. You know, the servants have an idea that the place is haunted, and I thought that if I sat here the ghost might take it upon himself to walk. I confess to a slight disappointment that it is only you who have appeared. I suppose it was n't you who knocked at my door?"

"No," I replied, laughing a little at her manner, "not unless it was you who switched off the lights as I was coming down from the fourth floor. I have been studying this chimney from the roof. I know something of the ways of electric switches, and they don't usually move of their own accord."

"Your coming to this house has been the greatest joy to me, Mr. Ames. I should not have imagined, in a chance look at you, that you were psychical, and yet such is clearly the fact. I assure you that I have not touched any switch since I left my room. It was unnecessary, as I found the lights on. And I acquit you of rapping, rapping at my chamber-door. It gives me the greatest satisfaction to assume that the house is haunted, and at any time you find the ghost, I beg that you will lose no time in presenting me. If the prowler is indeed one of King George's soldiers, hanged during the Revolution on the site of this house, I should like to have words with him. I have just been reading an article on the political corruption in Philadelphia in this magazine. It bears every evidence of truth, but if half of it is fiction I still feel that, as an American citizen, though denied the inalienable right of representation assured me in the Constitution, we owe that ghost an apology; for certainly nothing was gained by throwing off the British yoke, and that poor soldier died in a worthy cause."

She wore a remarkable lavender dressing-gown, and a night-cap such as I had never seen outside a museum. As she concluded her speech, spoken in that curious lilting tone which, from the beginning, had left me in doubt as to the seriousness of all her statements, she rose and, still clasping her magazine, made me a courtesy and was soon mounting the stair.

I heard her door close a minute later, and then, feeling that I had earned the right to repose, I went to my room and to bed.