XIV

LADY'S SLIPPER

I lighted my way with a candle through the lost chambers of the old house, up the hidden stairway, and out into the fourth-floor hall again. The old stair, I found on closer observation, reached only from the second to the fourth floor, and below this had been pieced with lumber carefully preserved from the earlier house. There was nothing so strange after all about the hidden stairway, though I was convinced that this had been no idea of Pepperton's, but that he had merely obeyed the orders of his eccentric client, the umbrella and dyspepsia-cure millionaire.

I had no sooner let myself through the secret door into the upper hall than I was aware of a disturbance in the library below. I heard exclamations from the men, and as I ran down toward the third floor Miss Octavia's voice rose above the tumult.

"We must have patience, gentlemen. Chimneys are subject to moods just like human beings; and we are fortunate in having in the house a gentleman who is an expert in such matters. I do not doubt that Mr. Ames even now has his hand upon the chimney's pulse, and that he will soon solve this perplexing problem."

"If you wait for that man to mend your chimney you will wait until doomsday."

So spake John Stewart Dick, taking his vengeance of me with my client and hostess. I might have forgiven him; but I could not forgive Hartley Wiggins.

"He does n't know any more about chimneys than the man in the moon," my old friend was saying, between coughs.

And then quite unmistakably I smelt smoke, and bending further over the rail and peering down the stair-well I saw smoke pouring from the library into the hall. It seemed to be in greater volume to-night than at previous manifestations. A gray-blue cloud was filling the lower hall and rising toward me. I ran quickly to the third floor, to the chamber whose fireplace was served by the library chimney. The lights in the third-floor hall winked out as I opened the door,—I heard a step behind me somewhere; but I did not trouble about this. The switch inside the unused guest-chamber responded readily to my touch, and on kneeling by the hearth I found it cold, as I had expected. There was absolutely no way of choking the library flue at this point, for, as I had established earlier, all the fireplaces in this chimney had their independent flues. Pepperton would never have built them otherwise, and no one but a skilled mason could have tapped the library flue here or higher up, and the work could not have been done without much noise and labor.

The hall outside was still dark, and I did not try the switch. The pursuit was better carried on in darkness, and I had by this time become accustomed to rapid locomotion through unlighted passages. I leaned over the stair-well and heard exclamations of surprise at the sudden cessation of the smoke, which had evidently abated as abruptly as it had begun. The windows and doors had been opened, and the company had returned to the library.

"Quite extraordinary. Really quite remarkable!" they were saying below. I heard Cecilia's light laughter as the odd ways of the chimney were discussed. And as I stood thus peering down and listening, the Swedish maid's blonde head appeared below me, bending over the well-rail on the second floor. She too was taking note of affairs in the library, and as I watched her she lifted her head and her eyes met mine. Then, while we still stared at each other, the second-floor lights went out with familiar abruptness, and as I craned my neck to peer into the blackness above me I experienced once more that ghostly passing as of some light, unearthly thing across my face. I reached for it wildly with my hands, but it seemed to be caught away from me; and then as I fought the air madly, it brushed my cheek again. I have no words to describe the strange effect of that touch. I felt my scalp creep and cold chills ran down my spine. It seemingly came from above, and it was not like a hand, unless a hand of wonderful lightness! Certainly no human arm could reach down the stair-well to where I stood. And in that touch to-night there was something akin to a gentle, lingering caress as it swept slowly across my face and eyes.

I waited for its recurrence a moment, but it came no more. Then on a sudden prompting I stole swiftly to the fourth floor, lighted my candle, and gazed about. I thought it well to let the electric light alone, for my ghost had once too often plunged me into darkness at critical moments, and a candle in my hands was not subject to his trickery.

The hall was perfectly quiet. The door leading down the hidden stair was invisible, and I had not yet learned how it might be opened from the hall, though Mr. Bassford Hollister had undoubtedly left the house by this means after my interview with him on the roof. And reminded of the roof, I opened the trunk-room door and peered in. The candle-light slowly crept into its dark corners, and looking up I marked the presence of the trap-door secure in the opening. As I stood on the threshold of the trunk-piled room, my hand on the knob and the candle thrust well before me, I heard a slight furtive movement to my left and behind the door. I was quite satisfied now that I was about to solve some of the mysteries of the night, and to make sure I was unobserved—for having gone so far alone I wanted no partners in my investigations—I listened to the murmur of talk below for a moment, then cautiously advanced my candle further into the room. I was not yet so valiant, even after all my night-prowlings and explorations of hidden chambers, but that I thrust the light in well ahead of me and bent my wrist so that the candle's rays might dispel the last shadow that lurked behind the door before I suffered my eyes to look upon the goblin. I took one step and then cautiously another, until the whole of the trunk-room was well within range of my vision.

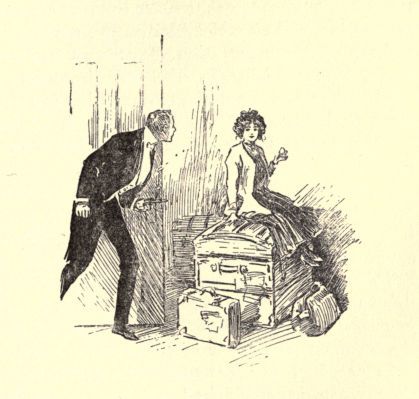

And there, seated on a prodigious trunk frescoed with labels of a dozen foreign inns, I beheld Hezekiah!

Seated on a prodigious trunk frescoed with labels

of a dozen foreign inns, I beheld Hezekiah!

As I recall it she was very much at her ease. She sat on one foot and the other beat the trunk lightly. She was bareheaded, and the candle-light was making acquaintance with the gold in her hair. She wore her white sweater, as on that day in the orchard; and with much gravity, as our eyes met, she thrust a hand into its pocket and drew out a cracker. I was not half so surprised at finding her there as I was at her manner now that she was caught. She seemed neither distressed, astonished nor afraid.

"Well, Miss Hezekiah," I said, "I half suspected you all along."

"Wise Chimney-Man! You were a little slow about it though."

"I was indeed. You gave me a run for my money."

She finished her cracker at the third bite, slapped her hands together to free them of possible crumbs, and was about to speak, when she jumped lightly from the trunk, bent her head toward the door, and then stepped back again and faced me imperturbably.

"And now that you've found me, Mr. Chimney-Man, the joke's on you after all."

She laid her hand on the door and swung it nearly shut. I had heard what she had heard: Miss Octavia was coming upstairs! She had exchanged a few words with the Swedish maid on the second-floor landing, and Hezekiah's quick ear had heard her. But Hezekiah's equanimity was disconcerting: even with her aunt close at hand she showed not the slightest alarm. She resumed her seat on the trunk, and her heel thumped it tranquilly.

"The joke's on you, Mr. Chimney-Man, because now that you 've caught me playing tricks you've got to get me out of trouble."

"What if I don't?"

"Oh, nothing," she answered indifferently, looking me squarely in the eye.

"But your aunt would make no end of a row; and you would cause your sister to lose out with Miss Octavia. As I understand it, you 're pledged to keep off the reservation. It was part of the family agreement."

"But I'm here, Chimney-pot, so what are you going to do about it?"

"Mr. Ames! If you are ghost-hunting in this part of the house"—

It was Miss Octavia's voice. She was seeking me, and would no doubt find me. The sequestration of Hezekiah became now an urgent and delicate matter.

"You caught me," said Hezekiah, calmly, "and now you've got to get me out; and I wish you good luck! And besides, I lost one of my shoes somewhere, and you've got to find that."

In proof of her statement she submitted a shoeless, brown-stockinged foot for my observation.

"The one I lost was like this," and Hezekiah thrust forth a neat tan pump, rather the worse for wear. "I was on the second floor a bit ago," she began, "and lost my slipper."

"In what mischief, pray?"

"Mr. Ames," called Miss Octavia, her voice close at hand.

"I wanted to see something in Cecilia's room; so I opened her door and walked in, that's all," Hezekiah replied.

"Wicked Hezekiah! Coming into the house is bad enough in all the circumstances. Entering your sister's room is a grievous sin."

"If, Mr. Ames, you are still seeking an explanation of that chimney's behavior"—

It was Miss Octavia, now just outside the door.

"Don't leave that trunk, Hezekiah," I whispered. "I'll do the best I can."

Miss Octavia met me smilingly as I faced her in the hall. She had switched on the lights, and my candle burned yellowly in the white electric glow.

Miss Octavia held something in her hand. It required no second glance to tell me that she had found Hezekiah's slipper.

"Mr. Ames," she began, "as you have absented yourself from the library all evening, I assume that you have been busy studying my chimneys and seeking for the ghost of that British soldier who was so wantonly slain upon the site of this house."

"I am glad to say that not only is your surmise correct, Miss Hollister, but that I have made great progress in both directions."

"Do you mean to say that you have really found traces of the ghost?"

"Not only that, Miss Hollister, but I have met the ghost face to face,—even more, I have had speech with him!"

Her face brightened, her eyes flashed. It was plain that she was immensely pleased.

"And are you able to say, from your encounter, that he is in fact a British subject, uneasily haunting this house in America long after the Declaration of Independence and Washington's Farewell Address have passed into literature?"

"You have never spoken a truer word, Miss Hollister. The ghost with whom or which I have had speech is still a loyal subject of the King of England. But by means which I am not at liberty to disclose, I have persuaded him not to visit this house again."

"Then," said Miss Hollister, "I cannot do less than express my gratitude; though I regret that you did not first allow me to meet him. Still, I dare say that we shall find his bones buried somewhere beneath my foundations. Please assure me that such is your expectation."

She was leading me into deep water, but I had skirted the coasts of truth so far; and with Hezekiah on my hands I felt that it was necessary to satisfy Miss Hollister in every particular.

"To-morrow, Miss Hollister, I shall take pleasure in showing you certain hidden chambers in this house which I venture to say will afford you great pleasure. I have to-night discovered a link between the mansion as you know it and an earlier house whose timbers may indeed hide the bones of that British soldier."

"And as for the chimney?"

"And as for the chimney, I give you my word as a professional man that it will never annoy you again, and I therefore beg that you dismiss the subject from your mind."

I saw that she was about to recur to the shoe she held in her hand and at which she glanced frequently with a quizzical expression. This, clearly, was an issue that must be met promptly, and I knew of no better way than by lying. Hezekiah herself had plainly stated, on the morning of that long, eventful day, when she walked into the breakfast-room in her aunt's absence and explained Cecilia's trip to town, that it was perfectly fair to dissimulate in making explanations to Miss Hollister; that, in fact, Miss Octavia enjoyed nothing better than the injection of fiction into the affairs of the matter-of-fact day. Here, then, was my opportunity. Hezekiah had thrown the responsibility of contriving her safe exit upon my hands. No doubt, while I held the door against her aunt, that remarkable young woman was coolly sitting on the trunk within, eating another cracker and awaiting my experiments in the gentle art of lying.

"Miss Hollister," I began boldly, "the slipper you hold in your hand belongs to me, and if you have no immediate use for it I beg that you allow me to relieve you of it."

"It is yours, Mr. Ames?"

A lifting of the brows, a widening of the eyes, denoted Miss Octavia's polite surprise.

"Beyond any question it is my property," I asserted.

"Your words interest me greatly, Mr. Ames. As you know, the grim hard life of the twentieth century palls upon me, and I am deeply interested in everything that pertains to adventure and romance. Tell me more, if you are free to do so, of this slipper which I now return to you."

I received Hezekiah's worn little pump into my hands as though it were an object of high consecration, and with a gravity which I hope matched Miss Octavia's own. I was, I think, by this time completely hollisterized, if I may coin the word.

"As I am nothing if not frank, Miss Hollister, I will confess to you that this shoe came into my possession in a very curious way. One day last spring I was in Boston, having been called there on professional business. In the evening, I left my hotel for a walk, crossed the Common, took a turn through the Public Garden, where many devoted lovers adorned the benches, and then strolled aimlessly along Beacon Street."

"I know that historic thoroughfare well," interrupted Miss Hollister, "as my friend Miss Prudence Biddeford has lived there for half a century, and once, while I was staying in her house, she gave me her recipe for Boston brown bread, thereby placing me greatly in her debt."

"Then, being acquainted with the neighborhood and its sublimated social atmosphere, you will be interested in the experience I am about to describe," I continued, reassured by Miss Octavia's sympathetic attention to my recital. "I was passing a house which I have not since been able to identify exactly, though I have several times revisited Boston in the hope of doing so, when suddenly and without any warning whatever this slipper dropped at my feet. All the houses in the neighborhood seemed deserted, with windows and doors tightly boarded, and my closest scrutiny failed to discover any opening from which that slipper might have been flung. The region is so decorous, and acts of violence are so foreign to its dignity and repose, that I could scarce believe that I held that bit of tan leather in my hand. Nor did its unaccountable precipitation into the street seem the act of a housemaid, nor could I believe that a nursery governess had thus sought diversion from the roof above. I hesitated for a moment not knowing how to meet this emergency; then I boldly attacked the bell of the house from which I believed the slipper to have proceeded. I rang until a policeman, whose speech was fragrant of the Irish coasts, bade me desist, informing me that the family had only the previous day left for the shore. The house he assured me was utterly vacant. That, Miss Hollister, is all there is of the story. But ever since I have carried that slipper with me. It was in my pocket to-night as I traversed the upper halls of your house, seeking the ghost of that British soldier, and I had just discovered my loss when I heard you calling. In returning it you have conferred upon me the greatest imaginable favor. I have faith that sometime, somewhere, I shall find the owner of that slipper. Would you not infer, from its diminutive size, and the fine, suggestive delicacy of its outlines that the owner is a person of aristocratic lineage and of breeding? I will confess that nothing is nearer my heart than the hope that one day I shall meet the young lady—I am sure she must be young—who wore that slipper and dropped it as it seemed from the clouds, at my feet there in sedate Beacon Street, that most solemn of residential sanctuaries."

"Mr. Ames," began Miss Hollister instantly, with an assumed severity that her smile belied, "I cannot recall that my niece Hezekiah ever visited in Beacon Street; yet I dare say that if she had done so and a young man of your pleasing appearance had passed beneath her window, one of her slippers might very easily have become detached from Hezekiah's foot and fallen with a nice calculation directly in front of you. But now, Mr. Ames, will you kindly carry your candle into that trunk-room?"

And I had been pluming myself upon the completeness of my hollisterization! There was nothing for me but to obey, and my heart sank as my imagination pictured Hezekiah's discomfiture when we should find her seated on the huge trunk behind the door. And that stockinged foot already called in appealing accents to the shoe I held in my hand! The foundations of the world shook as I remembered the compact by which Hezekiah was excluded from the house, and realized what the impending discovery would mean to Cecilia, her father, and the wayward Hezekiah, too! But I was in for it. Miss Octavia indicated by an imperious nod that I was to precede her into the trunk-room, and I strode before her with my candle held high.

But the sprites of mystery were still abroad at Hopefield. The room was unoccupied save for the trunks. Hezekiah had vanished. Instead of sitting there to await the coming of her aunt, she had silently departed, without leaving a trace. Miss Hollister glanced up at the trap-door in the ceiling, and so did I. It was closed, but I did not doubt that Hezekiah had crawled through it and taken herself to the roof. Miss Octavia would probably order me at once to the battlements; but worse was to come.

"Mr. Ames," she said, "will you kindly lift the lid of that largest trunk."

I had not thought of this, and I shuddered at the possibilities.

She indicated the trunk upon which Hezekiah had sat and nibbled her cracker not more than ten minutes before. Could it be possible that when I lifted the cover that golden head would be found beneath? My life has known no blacker moment than that in which I flung back the lid of that trunk. I averted my eyes in dread of the impending disclosure and held the candle close.

But the trunk was empty, incredibly empty! My courage rose again, and I glanced at Miss Octavia triumphantly. I even jerked out the trays to allay any lingering suspicion. Why had I ever doubted Hezekiah? Who was she, the golden-haired daughter of kings, to be caught in a trunk? She had slipped up the ladder while I talked to her aunt and was even now hiding on the roof; but it was not for me to make so treasonable a suggestion. Miss Octavia might press the matter further if she liked, but I would not help her to trap Hezekiah.

Miss Hollister did not, to my surprise and relief, suggest an inspection of the roof. She nodded her head gravely and passed out into the hall.

"Mr. Ames, if I implied a moment ago that I doubted your story of the dropping of that tan pump from a Beacon Street roof or window, I now tender you my sincerest apologies."

She put out her hand, smiling charmingly.

"Pray return to the occupations which were engaging you when I interrupted you. You have never stood higher in my regard than at this moment. To-morrow you may tell me all you please of the ghost and the mysteries of this house, and I dare say we shall find the bones of that British soldier somewhere beneath the foundations. As for that trifling bit of leather you hold in your hand, it's rather passé for Beacon Street. The next time you tell that story I suggest that you play your game of drop the slipper from a window in Rittenhouse Square, Philadelphia. Still, as I always keep an umbrella in the check-room of the Parker House, I would not have you imagine that I look upon Boston as an unlikely scene for romance. The last time I was there a Mormon missionary pressed a tract upon me in the subway, and I can't deny that I found it immensely interesting.”