XVI

JACK O' LANTERN

I hurried back to the trunk-room and had soon gained the roof. The moon was harassed by flying clouds that obscured it fitfully, and a keen wind swept the hills. I crept over the several levels of roof thinking that any moment I should come upon Hezekiah; I searched a second time, peering behind chimney-pots, and into dark angles; but to my disappointment and chagrin my young lady of the single slipper was nowhere in sight. I found, however, lying near the library chimney, a trunk-tray that required no explanation. With this Hezekiah had blocked the flue, and I smiled as I pictured her tip-toeing to reach the chimney-crock, and dropping the tray across the top. How gleefully she must have chuckled as she waited for the flue to fill and send the smoke ebbing back into the library, to the discomfiture of her aunt and sister and the suitors gathered about the hearth! The spirit of mischief never whispered into a prettier ear a trick better calculated to cause confusion.

I had thought Hezekiah secure when I locked the trunk-room door, but I had not counted upon the versatility and resourcefulness of that young person. I dropped to the second roof-level and inspected the down-spouts, but it was incredible that she had sought the earth by this means. I swung myself to a third level, and after much groping for my bearings, decided that an athletic girl of Hezekiah's venturesome disposition might, if she set no great store by her neck, clamber off the kitchen-roof by means of a tall maple whose branches now raspingly called attention to their slight contact with the house. It was here that the walls of Hopefield thrust themselves into the shoulder of a rough rocky knoll, and it was perfectly clear now that the chambers of the earlier house around which the mansion had been built were neatly enfolded by the walls on the east side.

As the moon cruised into a patch of clear sky something white fluttered from a maple limb, and I bent and pulled it free. I took counsel of a match behind the kitchen chimney, and found that it was a handkerchief that had been knotted to the tip of the bough. No one but Hezekiah would have thought of marking her trail in this fashion. I held it to my face, and that faint perfume that had been a mystifying accompaniment of the passing of the mansion ghost became nothing more unreal than the orris in Hezekiah's handkerchief-case. The wind whipped the bit of linen spitefully in my hands. I reasoned that if Hezekiah the inexplicable had not meant for me to know the manner of her exit she need not have left this plain hint behind; but the swaying maple bough did not tempt me. I hurried back across the roof to secure the trunk-tray, resolved to dispose of it, seek the open, and find the errant Hezekiah if she still lingered in the neighborhood.

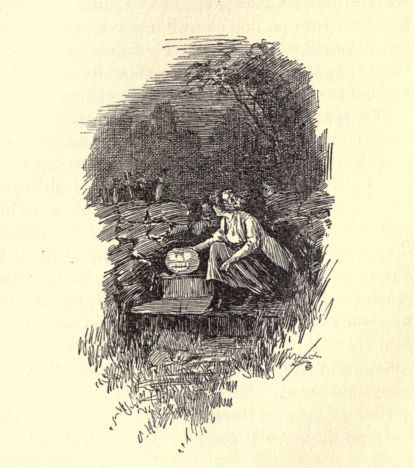

I looked off across the windy landscape before descending, and as my eyes ranged the dark I caught the glimmer of a light, as of a lantern borne in the hand, in the meadow beyond the garden. It paused, and was swung back and forth by its unseen bearer. It shed a curious yellow light and not the white flame of the common lantern; and now it rose a trifle higher and slowly resolved itself into a weird fantastic face.

Three minutes later I was out of the house, using the backstairs to avoid the company in the library, and had crossed the garden and crawled through the hedge. As I rose to my feet a voice greeted me cheerfully,—

"Well done, Chimney-Man! You were a little slow hitting the trail, but you do pretty well, considering. How did you manage with Aunt Octavia about that slipper? I had a narrow escape in the second-floor hall, when I came out of Cecilia's room. I must have lowered a record getting upstairs. And one shoe is n't a bit comfortable. Allow me to relieve you!"

"Here's your slipper. You ought to be ashamed of yourself."

"For losing my slipper? I thought Cinderella had made that respectable."

She placed her hand on my shoulder, lifted her foot, and drew the pump on with a single tug.

"Well, what did Aunt Octavia say?"

"Oh, she had thoughts too dark to express. You probably heard what we said. It was she who found the slipper!"

Hezekiah laughed. The wind caught up that laugh and whisked it away jealously.

"She found it and carried it to you, Chimney-Man, and I skipped just as you began that beautiful story about finding it in Beacon Street. Hurry and tell me how you got me out of it."

"How did you know I would try to explain it? You did a perfectly foolhardy thing in roaming the house that way, scaring Lord Arrowood nearly to death, to say nothing of me. Why should I help you?"

"Oh, you're a man and I was just a little girl who had lost her slipper," she replied. "I was sure you would fix it up."

"Well, I like your nerve, Hezekiah! I had to lie horribly to explain the slipper, and Miss Octavia did n't swallow more than half my yarn."

"Oh, well, if it was a good story, Aunt Octavia would n't mind. She'd have minded, though, if you had n't tried to get me out of it. That's the way with Aunt Octavia. I hope you made a romantic tale of it."

"I can't say that it would place me among the great masters of fiction, Hezekiah, but as lies go I think it had merit. And I 'll improve if I stay here much longer."

"Oh, you'll stay all right. Aunt Octavia has no intention of letting you go. When she left the Asolando that afternoon she met you, she had her plans all made for kidnapping you."

"She did n't tell you so, did she?"

"No; because I have n't seen her and I'm not supposed to see her, you know, until Cecilia is all fixed."

"Married?"

"Um," replied Hezekiah.

She drew from behind a boulder by which we stood a pumpkin of portable size, which I surmised had been carved into the most hideous of jack o' lanterns by the shrewd hand of Hezekiah. I took it from her with the excuse of relieving her, but really to turn the light of the fearsome thing more directly upon her. The wind blew her hair about her face; hers was an elfish face to-night. With a pleasant tingling I met her eyes. The light of a jack o' lantern is not of the earth earthy. Even when you know perfectly well that it's only a candle stuck in a pumpkin, you are not fully satisfied of its mundane character. In its glow one becomes a conspirator, ready for treason, stratagems and spoils. More concretely, in these moments a small archipelago of freckles revealed itself about Hezekiah's nose and caused my heart to palpitate strangely. Her sun-browned cheek was perilously near. I hoped that she would bend forever over the lantern, so that I might not lose the tiny shadows of her lashes, or, again, the laughter of her brown eyes as she glanced up to ask my judgment as to the security of the candle. She viewed her handiwork with feigned solicitude, the tip of her tongue showing between her lips. Then the mirth in her bubbled out, and she drew away and clapped her hands together like a child.

"Come!" she cried. "If you are good and won't begin preaching about my sins, I'll show you the funniest thing you ever saw in your life."

In my joy of seeing her I was neglecting Cecilia's commission. Very likely Hezekiah had forgotten all about her theft; hers, I reasoned, was a nature that delighted in the nearest pleasure. I would follow her jack o' lantern round the world for the chance of seeing the fun brighten in her brown eyes, but I had made a promise to Cecilia and I meant to fulfill it.

She led me now across the meadow, over a stone wall, up a steep slope, and by devious ways through a strip of woodland. I bore the jack o' lantern,—she had bidden me do it, with some notion, I did not question, of making me particeps criminis in whatever mischief was afoot. Dignified conduct in a man of twenty-eight, in his best evening clothes, carrying a jack o' lantern over stone walls, under clumps of briar, and through woods whose boughs clawed the night wildly! The moon lost and found under the flying scud was in keeping with the general irresponsibility of a world ruled by Hezekiah.

She swung along ahead of me with the greatest ease and certainty. Occasionally she flung some word back at me or whistled a few bars of a tune, and when I slipped and nearly fell on a smooth slope she laughed mockingly and bade me not lose the pumpkin. Once, when a boy, I stole a watermelon and bore it a mile to the rendezvous of my pirate band camped at a riverside; but carrying a pumpkin, even a hollow one, is attended with manifold discomforts. It would help, I reflected, to know just what I was lugging it for, but Hezekiah vouchsafed nothing. When I threatened to drop the grinning gargoyle she laughed and told me to trot along and not be silly; and a moment later she stopped and demanded that I repeat fully the story I had told her aunt of the finding of the slipper.

"You are better than I thought you were, Chimney-Man!" she declared, when I had concluded and added her aunt's comment. "You may be sure that tickled Aunt Octavia. You can lie almost as well as an architect. Aunt Octavia says architects are better liars than dress-makers."

"It was my weakness for the truth that caused me to abandon architecture. For heaven's sake, what are you up to?"

I had kept little account of the direction of our flight, and I was surprised that we had now reached the stile over which I had watched the passing of the suitors on the afternoon of my meeting with Hezekiah in the orchard.

"This is the appointed place," she remarked, taking the pumpkin from me and dropping down on the far side of the stile.

"Hezekiah, I've trotted across most of Westchester County after you, and my arm is paralyzed from carrying that pumpkin. I must know what you're up to right here, or I'll go home. Besides, there's a mist falling and you'll be soaked. What do you suppose your father thinks of your absence at this time of night?"

"Oh, he'll never forgive me for not letting him in on this. This is the grandest thing I ever thought of. Sit on this step and gently incline your ear toward the house. It's about time those gentlemen were leaving Cecilia, and they'll be galloping for their inn in a minute, and then"—

Hezekiah whistled the rest of it.

While we waited, she bade me reset the candle and snuff the wick, which I did of necessity with my fingers. Sitting on a stile with a pretty girl is an experience that has been commended by the balladists, but surely this felicity loses nothing where the night is fine. When you get used to sitting in a drizzle in your dress-suit, while your shirt-bosom assumes the consistency of a gum shoe and your collar glues itself odiously to your neck, I dare say the ordeal may be borne cheerfully, but my expressions of discomfort seemed only to amuse Hezekiah. While we waited for I knew not what, I tried once or twice to revert to the silver note-book, but without success. Hezekiah was a mistress of the art of evasion with her tongue as well as her feet!

"Wait till the evening performance is over and I'll talk about that. 'Sh! Quiet! Crawl over there out of the way, and when I say run, beat it for the road."

These last phrases were uttered in a whisper, her face close to my ear. She gave me a little push, and I withdrew a few yards and waited. The ground, I may say, was wet, and the drizzle had become a monotonous autumn rain.

The light of the lantern fell warmly upon Hezekiah's face as she held its illumined countenance toward her, crouching on the stile-steps. I heard now what her keener ear had caught earlier—the tramp of feet along the path. The suitors were returning to the inn, and the voices of one or two of them reached me. One—I thought it was Ormsby—was execrating the weather. They were stepping along briskly, and my remembrance of their retreat over this same stile through the amber evening dusk was so vivid that I knew just how they would appear if a light suddenly fell upon the path.

The light of the lantern fell warmly upon Hezekiah's face.

The nature of Hezekiah's undertaking suddenly dawned upon me. No one but Hezekiah could ever have devised anything so preposterous, so utterly lawless; but in spite of myself I waited in breathless eagerness for the outcome. I could not have interfered now, if I had wished to do so, without betraying her and involving myself in a predicament that could not redound to my credit.

Nearer and nearer came the patter of feet, and I heard, for I could not see, the scraping of Hezekiah's slipper,—a wet little shoe by now!—as she crept higher on our side of the stile. The first suitor groped blindly for the steps, slipped on the wet plank, growled, and rose to try again. That growl marked for me the leader of the van. Hartley Wiggins, beyond a doubt, and in no good humor, I guessed! The others, I judged, had trodden upon one another's heels at the moment Wiggins stumbled. Thus let us imagine their approach—six gentlemen in top hats headed for a stile on a chilly night of rain.

It was at this strategic moment that Hezekiah pushed into the middle of the stile-platform, its grinning face turned toward the advancing suitors, the jack o' lantern her hand had fashioned.

I marked its position by its faint glow an instant, but an instant only. The world reeled for a moment before the sharp cry of a man in fear. It cut the dark like a lash, and close upon it the second man yelled, in a different key, but no less in accents of terror. The first arrival had flung himself back, and so close upon him pressed the others and so unexpected was the halt, that the nine men seemed to have flung themselves together and to be struggling to escape from the hideous thing that had interposed itself in their path.

All was over in a moment. In the midst of the panic the lantern winked out, and instantly Hezekiah was beside me.

"Skip!" she commanded in a whisper; and catching my hand she led me off at a brisk run. When we had gone a dozen rods she paused. We heard voices from the stile, where the gentlemen were still engaged in disentangling themselves; and then the planks boomed to their steps as they crossed. They talked loudly among themselves discussing the cause of their discomfiture. The lantern, I may add, had been knocked off the stile by the thoughtful Hezekiah when she blew out the light.

A moment more and all sounds of the suitors had died away. I stood alone with Hezekiah in the midst of a meadow. She was breathing hard. Suddenly she threw up her head, struck her hands together, and stamped her foot upon the wet sod. I had waited for an outburst of laughter now that we were safely out of the way, but I had reasoned without my Hezekiah. Her mood was not the mood of mirth.

"Well, Hezekiah," I said when I had got my wind, "you pulled off your joke, but you don't seem to be enjoying it. What's the matter?"

"Oh, that Hartley Wiggins! I might have known it!"

"Known what?" I asked, pricking up my ears.

"That he would be afraid of a pumpkin with a candle inside of it. Did you hear that yell?"

"Anybody would have yelled," I suggested. "I think I should have dropped dead if you'd tried it on me."

"No, you would n't," she asserted with unexpected flattery.

"Don't be deceived, Hezekiah; I should have been scared to death if that thing had popped up in front of me."

"I don't believe it. I gave you a worse test than that. When I switched off the lights and swung a feather duster down the stair-well by a string and tickled your face you did n't make a noise like a circus calliope scaring horses in Main Street, Podunk. But that Wiggins man!"

"He's a friend of mine and as brave as a lion. Out in Dakota the sheriff used to get him to go in and quiet things when the boys were shooting up the town."

"Maybe; but he shied at a pumpkin and can be no true knight of mine. Cecilia may have him. I always suspected that he was n't the real thing. Why, he's even afraid of Aunt Octavia!"

"Well, I rather think we 'd better be!"

I wanted to laugh, but I did not dare. I was not prepared for the humor in which the panic of the suitors had left her. I did not quite make out—and I am uncertain to this day—whether she had really wished to test the courage of her sister's lovers or whether she had yielded to a mischievous impulse in carrying the jack o' lantern to the stile and thrusting it before those serious-minded gentlemen as they returned from Hopefield. In any event Hartley Wiggins was out of it so far as she, Hezekiah, was concerned. She trudged doggedly across the field until we came presently to the highway.

"My wheel's in the weeds somewhere; please pull it out for me. I'm going home."

"But not alone; I can't let you do that, Hezekiah."

"Oh, cheer up!" she laughed, aroused by my lugubrious tone. "And here's something you asked me for. Don't drop it. It's Cecilia's memorandum-book. Give it back to her, and be sure no one sees it, and you need n't look into it yourself. And we've got to have a talk about it and Cecilia. Let me see. There's an iron bridge across an arm of that little lake over there, and just beyond it a big fallen tree. To-morrow at nine o'clock I'll be there. I've got to tell you something, Chimney-Man, without really telling you. You'll be there, won't you?"

"I'll be there if I'm alive, Hezekiah."

I had found the wheel and lighted the lamp. She scouted my suggestion that I find a horse and drive her home. The lighting of the lamp required time owing to the wind and rain; but when its thin ribbon of light fell clearly upon the road, she seized the handle-bars and was ready to mount without ado.

She gave me her hand,—it was a cold, wet little hand, but there was a good friendly grip in it. This was the first time I had touched Hezekiah's hand, and I mention it because as I write I feel again the pressure of her slim cold fingers.

"Sorry you spoiled your clothes, but it was in a good cause. And you 're a nice boy, Chimney-Man!"

She shot away into the darkness, and the lamp's glow on the road vanished in an instant; but before I lost her quite, her cheery whistle blew back to me reassuringly.