CHAPTER XIV

CONCLUSION.

THAT’S right, Lily, place the books ready; get everything right for dear mother,” said George, as, with a step and manner, oh, how changed! he entered the drawing-room the next morning.

“I want you to see that I do not forget your advice. I am going to be a real comfort to mamma.”

“And so am I!” cried Eddy, with glee.

“My healthy arm shall be her stay,

And I will wipe her tears away!”

He stopped short, and stared in wonder at his brother. “Are you going to cry, Georgie?” he exclaimed.

“What is the matter, George, dear George?” cried Lily, looking alarmed.

“Sit down beside me, dear Lily and Eddy,” said George, when he had recovered his voice. “I want to speak with you quietly and seriously—I want to speak to you about our dear parents.”

“But is anything the matter?” repeated Lily.

“I am going to leave you—I am going to Bristol—I—”

He was interrupted by a passionate exclamation from Lily, and something like a howl from Eddy.

“I wish you to take my place—to be to those dear parents all that I once hoped to be; to obey them cheerfully, without a murmur; to try and find out their wishes, even before they can speak them; to—”

“But you shan’t go, Georgie; I won’t let you go!” cried Eddy, seizing his brother’s arm with both his hands, as if to detain him by force.

At that moment there was a knock at the door, and George turned very pale at the sound. The next minute Mrs. Ellerslie entered the drawing-room to receive the expected visitor. The lady’s eyes looked swollen and red, and her form drooped like a withering flower. Eddy popped a cushion on her chair, and Lily drew a footstool before it.

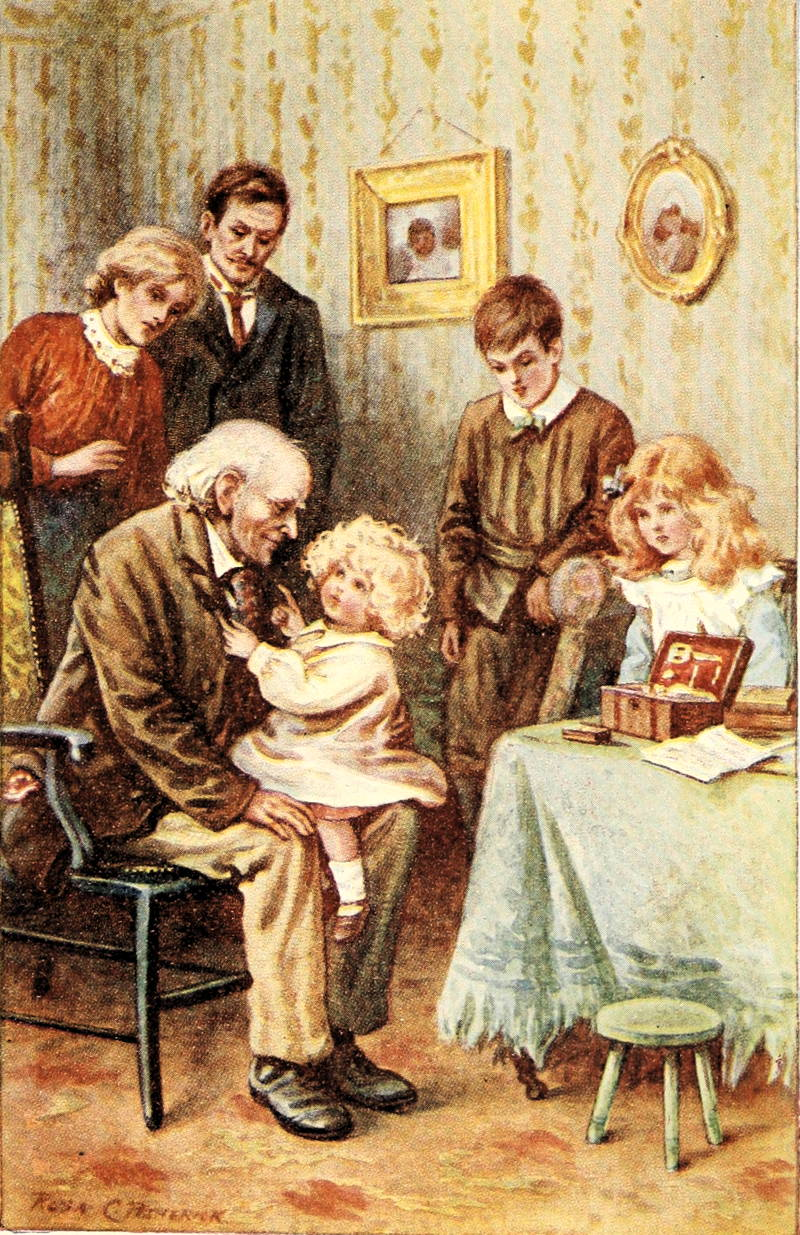

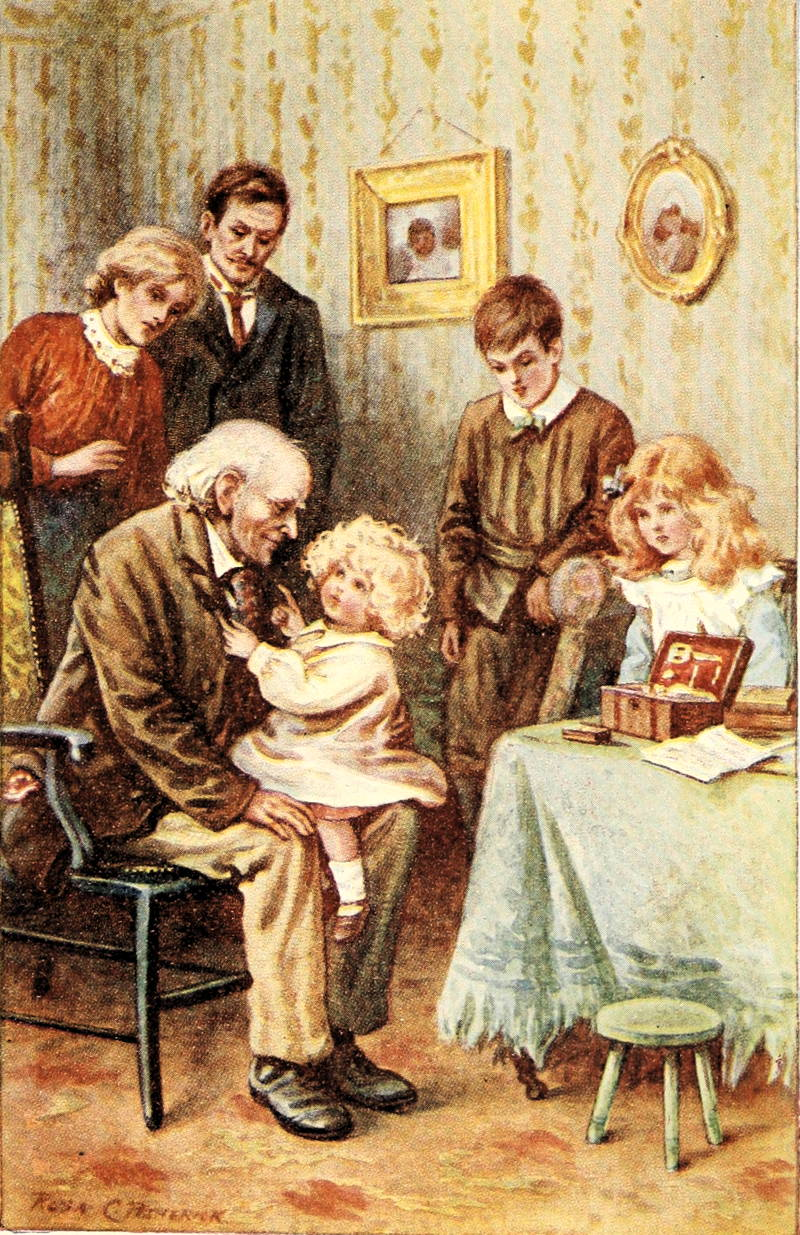

Mr. Ellerslie, whose voice had been heard on the stairs in conversation with some one whose cracked, peculiar tones grated harshly on the ear, now threw open the door and followed into the apartment a little shrunken figure, dressed in a snuff-coloured coat, considerably the worse for wear. I could not wonder, when I looked at the visitor, at poor George’s reluctance to exchange the society of all whom he loved so well for that of his cousin at Bristol. There was something shabby, mean, even dirty, in his appearance, which gave the impression that he was out of place in a gentleman’s house; while a terrible squint in his left eye, and a strange twitch in his face, which set Eddy laughing, made his countenance the reverse of agreeable.

Mr. Hardcastle, in an uncouth, awkward manner, shook hands with Mrs. Ellerslie, nodded to Lily, and chucked Eddy good-humouredly under the chin; then, clapping George heartily on the back, he said, “So, my man, you are going back with me to Bristol! That’s right. See that your trunk is packed by Monday; we’ll be off by the early train.”

“I shall be ready, sir,” answered the boy.

Mr. Hardcastle sat down, pulled out his snuff-box, took a pinch of its contents, part of which he bestowed on the carpet, then held out the box to Eddy, who examined with interest the picture on the lid.

“I’ll arrange it with you, Ellerslie, to-day,” said the old gentleman; “we’ll go to the city together, make all right, set all smooth.” He passed his fingers through his hair, and stretched out his legs with an air of satisfaction, in marvellous good-humour with himself.

“I am very sensible how much I am indebted to you,” began Mr. Ellerslie, making an effort to speak.

“Say nothing about it, say nothing about it—it’s all settled and done. When a man comes half-way to meet me, why it’s my way to go the other half to meet him. Eh, George?” he added, as if appealing to the boy, who stood silently and sadly leaning against the arm of the sofa.

George’s answer was a half-suppressed sigh.

“You look glumpish,” said the old gentleman, fixing the eye which did not squint on the boy. “You don’t wish to go with me, eh?”—the cracked voice had impatience in its tone.

“I wish to do—whatever is best for my parents.”

“But you don’t like going, eh?” said Mr. Hardcastle, resting his bony hands on his knees, and leaning forward with a look of peevish irritability.

“I cannot like—leaving my home for another,” answered George gravely; “but I am ready to do it—I do not complain.”

Mr. Hardcastle continued his sharp scrutiny of the boy’s countenance, as if he would read him through and through. There was a painful moment of silence—it was broken by little Eddy.

“You shan’t take away George,” said he, going close to the old man, and looking earnestly up into his face.

“I shan’t! shall I not? and why not, my little man?” said Mr. Hardcastle, lifting the child on his knee.

“Because—because—Georgie must not be sent far away like the compass, but stay here at home like the needle.”

“Like what?” exclaimed Mr. Hardcastle, laughing.

“It’s a story Georgie told us,” said the child, pulling the buttons on the coat of the old gentleman.

“Let’s hear his story, by all means, my dear.”

Poor Eddy looked exceedingly puzzled, for he had very little command of language, and did not know how to put his thoughts into words. At last he said, “Georgie told it to make us good, and busy, and kind, and a comfort to papa and mamma.”

“Ah! that must have been a capital story; I should like to hear you tell me all about it.”

“Eddy,” said his father, “how can you plague Mr. Hardcastle with your nonsense?”

“I beg your pardon, he does not plague me at all. It amuses me to hear what the little fellow has to say. So out with your improving story, Master Eddy!”

Eddy tells his story..

Poor Eddy turned round and looked at his brother; but George seemed disposed to render him no assistance. He glanced at Lily—she would not utter a word. He was left to his own resources.

“Well, once upon a time,” he began, but stopped short. “I can’t tell a story,” said the child; “it is too hard—I can only remember a bit of the fairy’s pretty song.”

“A little is better than nothing,” cried the old gentleman, much amused at the perplexed look of the child. “Let’s hear what the fairy sang.”

“It was something about what we all should do, Georgie said. It made me think I should like to do it too. This was it;” and keeping time with his fore-finger, he slowly repeated—

“What is marred, make right;

What is severed, unite;

And leave where’er you pass love’s golden thread of light!”

The hard features of the old man softened as he listened to the lisping child. “That’s the song, is it?” said he, stroking Eddy’s locks in rather an abstracted manner. “What is severed, unite,” he repeated to himself;—“here it is, What is united, sever!” and he glanced at George and his mother.

“That won’t do at all,” said Eddy, overhearing him; “that sounds bad—shocking bad!”

“Does it?” said Mr. Hardcastle, laughing. “Well, I really believe that it does. So George teaches you to be busy, and obedient, and kind, and makes you all happy; does he, eh?”

“Oh yes!” cried Eddy, jumping down and running up to his brother.

“It would be a shame to part you, then, it would be a shame!” said the old man, rising. “No, no; I am not so bad as that! George, stay with your parents; you are an honour to them, my boy! stay and be a comfort and blessing in your home!—And now, Ellerslie, shall we start for the city?”

I shall not attempt to describe the deep, intense joy which followed the utterance of these few words, the delight which sparkled in the eyes of George, or the fervent exclamation of thankfulness from his mother!—but none looked merrier than the kindhearted old man himself, unless it were our little friend Eddy.

I have often thought of that scene since, and talked it over with the Thimble. She has become too small for Lily’s finger now, but occupies a quiet corner in the box. The broken-pointed Scissors I have lost sight of for years. Lily has grown into a sweet, gentle young maiden, ever watchful to show kindness to those who need it, ever thoughtful of the feelings of others. Her mother speaks of her now as her “right hand;” and the bloom has returned to the lady’s pale cheek, and her brow is calm and serene. George has entered the Church, I understand; and Eddy, like the compass in the story, is pursuing his way on the wide ocean. But I have reason to believe that, in their different paths, both are pressing forward to the same happy goal, and in their intercourse with the world, as well as in their peaceful home, are living in the spirit of the song—

“On life’s ocean wide,

Your fellow-creatures guide,

And point to a shore beyond the stormy tide!

What is marred, make right;

What is severed, unite;

And leave where’er you pass love’s golden thread of light!”