THE VICTORY.

FRITZ ARNT was the son of a poor widow, who dwelt near the shore of the Rhine. He had been her chief comfort and helper since the day when Carl Gesner, the hard-hearted farmer, had turned her and her three children out of their cottage the very afternoon on which the funeral of her husband had taken place. In the middle of winter the sobbing widow had to go forth from her home; carrying little with her, for Carl had seized on most of her goods for the rent, which during her husband’s long illness had fallen into arrears. Yes! he had kept the very bed upon which her husband had breathed his last; and but for the kindness of neighbours, Frau Arnt and her children would have had to sleep on straw.

Fritz had been but a young boy then; but he had never forgotten the bitterness of that moment when his mother, sad, sick, and desolate, had pleaded with clasped hands to her hard-hearted landlord for a little delay, and had pleaded in vain. Fritz had helped to nurse her through a dangerous illness which followed. The boy had never forgiven the farmer, but had often said in his heart that a time would come when he should make Carl Gesner bitterly repent having nearly caused the death of a sorrowing widow.

Since that sad winter Fritz had worked hard to help to support the family, and with increasing success. His wages for field labour eked out what Frau Arnt earned at the lace-pillow; and something like comfort was beginning to be enjoyed in his humble home, when the sound of the war-bugle was heard in his native valley, and the news spread far and wide that a fierce and terrible foe was on the march to invade the German’s Fatherland. Fritz was under the age for military service which all Prussians are bound to give; but he had a strong arm, and his country needed strong arms. He was eager to serve his king, and be one of the throngs that from every hamlet were hasting to join the ranks of the army.

But Fritz was too good a son to go without his widowed mother’s consent. He had not only learned, but kept, that divine commandment, HONOUR THY FATHER AND THY MOTHER. The lad would not quit his home without obtaining that leave which he was almost afraid to ask.

Frau Arnt was sitting with her lace-pillow on her knee, the glow of the evening sun shining on her thin, worn face, when Fritz drew near. He watched for some moments her busy fingers plying the threads, before he observed,—

“My brother Wilhelm is a strong boy now, and older than I was when we first came here.”

He paused: there was no reply. The widow guessed what was coming, and her fingers moved faster than before.

“Farmer Schwartz says that he would give Wilhelm my place, mother, and make his wages the same as mine, if—”

Fritz stopped again, and glanced anxiously into the face of his mother. She suddenly paused in her work; her hands were trembling too much to guide the threads, and her eyes were swimming in tears, so that she could not see the pattern. Fritz knew then that his mother read his thoughts, and that there was a struggle in her mind between her love for him and a sense of duty. It was some time before, in a very low voice, he spoke again:—

“Mother, men are needed to guard your home and other homes. You have two sons; will you not spare one to your Fatherland?”

The widow suddenly rose; her pillow dropped from her knee; her arms were thrown around the neck of her son, and her face was buried on his shoulder, as she sobbed forth,—

“Go, and the Lord be with thee, my son!”

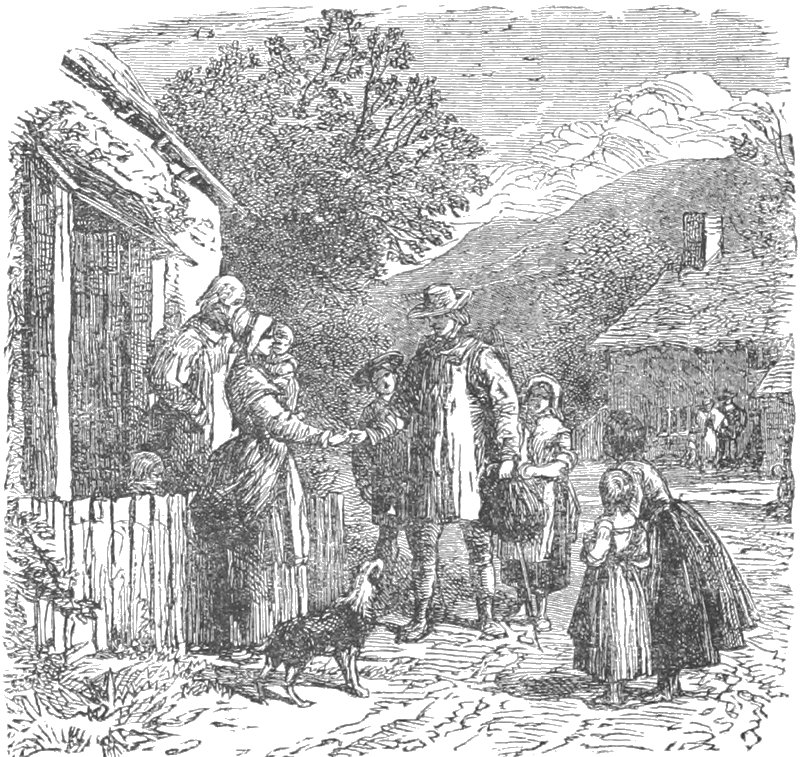

FRITZ BIDDING GOOD-BYE TO HIS FRIENDS.

Very little time was spent in preparation by Fritz. The very next day he set out for the army. But before doing so, Fritz, accompanied by Wilhelm and their sister, went round the hamlet to bid good-bye to his friends. There was but one house which Fritz would not enter: it was that at whose door stood Carl Gesner and his wife, watching him as he bade farewell to friends on the opposite side of the road. At that time of excitement all Prussians were ready to show kindness to the brave defenders of their land; and Fritz knew that even Carl might be willing to make friends with a young soldier then, for the farmer had such patriotic zeal as to talk of joining the army himself. But Fritz would have nothing to do with Carl Gesner. “I will never cross the threshold nor grasp the hand of a man who turned us all out of doors, and nearly killed my mother,” muttered Fritz to himself, as he strode past the house of the farmer.

I will not dwell upon the bitter parting. Frau Arnt felt as if her heart would break; for she had heard so much of the power of France, that she deemed that her country was entering on a desperate struggle indeed, and that there was small chance that she would ever again behold her gallant young son. But the frau was a pious woman: she committed her boy to the care of a heavenly Father; and her last words to Fritz as they parted were, “Remember that it is God that giveth the victory.”

Often these encouraging words came back to the young soldier’s mind, as he marched with his comrades singing the soul-stirring song,—

“Dear Fatherland! no fear be thine;

Firm hearts and true watch by the Rhine!”

The regiment to which Fritz was attached was not engaged in the first battles. Several weeks passed before the youth was brought face to face with strife and death. The time was not spent idly. Fritz learned much that a soldier must know: he learned not only his drill exercise, but also how to endure hardship and toil.

At last Fritz’s regiment joined one of the army corps on the eve of a great battle. At the end of a long march Fritz reached the Prussian camp, and from a hill-side looked for the first time on the enemy’s hosts ranged on the opposite slopes. They were near enough for Fritz to catch the faint sound of their trumpet-call as the sun went down—near enough for him to distinguish the colour of their flags, before night shut out all but camp-fires from his view. And Fritz heard and saw what made his heart beat fast—the booming of French cannon, and the puffs of white smoke which rose above them; for a few shots were exchanged on that evening between the two armies that were so soon to close in deadly strife.

The eve of a first battle is a solemn time even to the bravest of men. “One of these cannon may bring my death-summons to-morrow,” thought Fritz, as he stood leaning on his gun, with his eyes turned towards the enemy’s quarters, which darkness was now shrouding from his sight. Then from the lad’s lips rose the German battle-prayer—that noble hymn composed by the poet Körner, who fell defending his country against the First Napoleon:—

“Father, I call on Thee!

Through the dense smoke the war-thunder is pealing;

Over my head the fierce lightning is wheeling:

Ruler of armies, I call on thee;

Father, O guide Thou me!

“Father, now lead me on!

Lead me to slaughter, or lead me to glory;

Since Thou ordainest whatever is before me,

Whate’er Thou willest, Thy will be done

To Thee I bow alone!

“Father, O bless and guide!

Thine is my life, and to Thee I commend it;

Thou didst bestow it, and Thou canst defend it:

In life, in death, with me abide,

And be Thou glorified!”

“And can I thus calmly commend my spirit to my heavenly Father?” thought Fritz. “If, as is likely enough, I am to be one of those who will lie stiff and stark in yon valley before the setting of to-morrow’s sun, am I sure that I have made my peace with God so that death need have no terrors for me?”—In how many brave souls must such thoughts arise on the eve of battle!

“My mother has often told me that we are saved by faith”—thus Fritz went on with his musings—“and I can say from my heart that I do believe. Yes! I believe in Him through whom is forgiveness of sins; I believe in His mercy, His merits, His Word”—Fritz almost started, for at that moment one sentence spoken by the Holy One flashed across his memory, and by that sentence he stood condemned:—“IF YE FORGIVE NOT MEN THEIR TRESPASSES, NEITHER WILL YOUR FATHER FORGIVE YOUR TRESPASSES.” Fritz Arnt thought of Carl Gesner.

“Have I not nourished hatred and malice in my heart for years?” thought the young soldier. “Then have my very prayers been a mockery; then am I still UNFORGIVEN. I dare face an earthly foe, but how dare I face a heavenly Judge? But how can I conquer these feelings of dislike and revenge—these enemies in my heart? They seem to be part of my very nature.”

Then the night breeze seemed to whisper to the young soldier the words last heard from the lips of his mother,—“It is God that giveth the victory.” Fritz sank on his knees and prayed, not now for help in the coming strife with the enemies of his country, but for help in the present struggle with the enemies of his soul.

Very fearful was the battle on the following day. Let us pass over the fearful details, nor describe how God’s creatures destroyed each other by thousands, till the Germans fought their way to victory over heaps of the slain. Their triumph was dearly purchased indeed; numbers of their bravest fell beneath the deadly fire of the French. Fritz rushed forward, with a few soldiers of his own and of another regiment, to seize a French gun which had made terrible havoc in the Prussian lines. Almost before the smoke from the last discharge of that gun had cleared away, there was a hand-to-hand struggle around it. In the confusion of that struggle Fritz saw a Prussian fall under a blow from a Frenchman’s sword. Even as he fell, Fritz caught a glimpse of his face: begrimed as it was with smoke and dust, the young soldier recognized the features of Carl Gesner! The Frenchman’s sword was raised again to kill the prostrate Prussian; but Fritz sprang forward, warded the blow, and at the same moment himself fell to the earth, struck in the thigh by a musket ball from another quarter.

Sudden darkness seemed to come over the wounded youth. A rushing noise in his ears drowned even the roar of cannon and the sound of tumult and shouting. Fritz Arnt swooned, and lay for many hours senseless under the muzzle of the gun which he had helped to capture.

When Fritz again opened his eyes, the tumult had died away; the battle was over; the calm stars were looking down from the midnight sky upon heaps of dead and dying. Fritz was in severe pain, but gradually quite recovered his senses, and could think again on his mother, and silently lift up his heart in the battle-prayer.

“Oh for one drop of water! I am dying of thirst!” groaned a wounded Prussian beside him.

The voice was that of Carl Gesner, who lay within a yard’s length of the youth who had saved his life from the Frenchman’s sword. Fritz made no reply. His lips too were parched and dry, and the fever thirst was upon him. Oh, how he longed for one draught of the pure fresh spring which gushed forth near the home of his widowed mother!

Presently lights were seen moving over the dark field: helpers of the wounded were going about on their errand of mercy. But there were too few of them to do the work quickly; for so many poor soldiers lay low that it was impossible in one night to relieve the terrible wants of all. With keen anxiety Fritz watched the distant lights, while Carl Gesner lay groaning beside him. At last a torch-bearer drew near, with a companion who bore a red cross on his arm and a large water-flask in his hand.

“I must go back to refill the flask; there are but a few drops of water left in it,” observed one of the men.

Fritz half raised himself on his elbow with a desperate effort.

“Help! help!” he cried out; for the very name of water made his thirst more intense.

“Here, my poor fellow! would that I had more with me!” said the bearer of the flask, stooping down to pour its last contents into the mouth of the wounded young soldier.

There was again a faint groan from Carl Gesner. He was then too faint to speak, but his groan fell on the ear of Fritz Arnt. “IF THINE ENEMY THIRST, GIVE HIM TO DRINK.” Fritz in the midst of his pain and want remembered the Lord’s command.

“Give it to that man instead,” he murmured; “he is more badly wounded than I am.” And with the generous request on his lips the brave soldier fainted again.

There lay Fritz, twice a conqueror—over the foe, and over himself. God had given him the victory.

When Fritz awoke again from what had seemed the slumber of death, he found himself in an hospital, to which the helpers of the wounded had borne him. There he lay for many weeks, during the latter part of the time nursed by his own dear mother. During his slow recovery, Fritz was cheered by the knowledge that he had been enabled to do his duty, and by tidings of one triumph after another gained by the arms of Prussia.

Fritz was at length able to leave the hospital, but he was too lame to rejoin the army. He had to go back with his mother to their poor home, which would be poorer, Fritz thought, than ever; for he was too weak for labour, and while his mother had been nursing him, she could not earn money by work.

On a morning in September, Frau Arnt and her wounded son returned to their native village. Fritz, weak and lame, had to lean on his mother’s arm for support, as the two walked the short distance from the railway station.

“Strange that Wilhelm should not have been here to welcome us!” observed the widow. “He cannot have received my note to tell of our coming.”

“Don’t let us pass our old cottage, mother,” said Fritz faintly. “I have never liked to go near it since Carl Gesner turned us out of it.”

“Nay, my son; we must take the shortest path home,” said the widow. “And as for Carl Gesner, have you not told me how freely you have forgiven him?”

Turning a corner of the road as she spoke, the old cottage lay straight before her.

“Why, there is Carl Gesner himself,” exclaimed Fritz, “nailing something to the wall!”

“And Wilhelm helping him in his work!” cried the widow, in great surprise.

At the sound of his mother’s voice, Wilhelm turned suddenly round, and, at the sight of her and his brother, uttered a loud exclamation. The boy then bounded towards them, his eyes sparkling with joy at Fritz’s return, and with another joy the cause of which he had yet to keep a secret.

It was not a secret long. The glad exclamation uttered by Wilhelm drew the attention of Carl Gesner, whose back had been turned. The moment that he saw Fritz Arnt he hastened towards him.

“My brother-soldier, my brave young preserver, welcome!” cried Carl, holding out his hand; and Fritz would not now refuse to exchange a cordial grasp with the man whom he once had hated. “I joined the army soon after you did,” continued Carl Gesner. “Like yourself, I have had to leave it on account of my wounds, though my recovery has been more rapid than yours. You look weary, but rest is at hand. Here is your home; it is put into perfect repair. Let us enter it now together.”

“Our home!” exclaimed Fritz and his mother in a breath.

“Yes, yours to the end of your days,” said Carl Gesner. “Frau Arnt, I owe to your noble boy my life; and more than my life. I do not attempt to repay my debt by the gift of his father’s cottage, which I would that you had never left. I but show that I acknowledge that debt. You will find the place improved,” he added, more cheerfully. “We have been planting creepers to train up the wall; and I have had a board painted, to be hung up just below the lattice, to serve as a memorial of the battle in which Fritz and I fought side by side.”

Carl Gesner took up the board as he spoke, and turned it so that all could see the gilded letters upon it. Fritz glanced at the inscription, then at his mother, and smiled. Was it not strange that Carl Gesner should have happened to choose for the motto on the wall of the cottage the very words which had had such a deep effect on the heart of Fritz? There they were, to shine brightly from henceforth on his happy home, the parting words of his mother,—

It is God who giveth the Victory.