CHAPTER VI

THE WARS OF THE ROSES

THERE is much that is tedious in the accounts of the Wars of the Roses. One battle is gained by the Lancastrians, and the next by the Yorkists, this continuing for years in a see-saw fashion. At first the war was not marked by much bloodthirstiness, but after the Battle of Towton no quarter was given on either side, the prisoners being murdered in cold blood, the most conspicuous amongst them being beheaded. This summary method of disposing of the captives accounts for the small number of State prisoners in the Tower during the twenty years of internecine warfare which almost annihilated the peerage. Here are a few of the principal battles fought throughout the length and breadth of England between 1455 and 1461. In 1458 was fought the battle of St Albans, in which Somerset was defeated and slain. In 1459 Lord Audley was slain by Salisbury, who gained the Battle of Blore Heath; in 1460 the Yorkists, led by Salisbury, Warwick, and March (afterwards Edward IV.), defeated the King at Northampton and took him prisoner; in the same year Margaret’s army routed the Yorkists at Wakefield, where the Duke of York was killed, and Salisbury was beheaded at Pontefract. In 1461 the Lancastrians were defeated at the Battle of Mortimer’s Cross by Edward, the son of the Duke of York, and the future King; and in that same year the decisive Battle of Towton was also gained by him, the Lancastrian cause receiving its death-blow. Three months later, Edward was crowned by the style of Edward the Fourth, and his brothers George and Richard were made Dukes of Clarence and Gloucester respectively, whilst poor, harmless, half-witted Henry was proclaimed a traitor.

When Henry was told that he had no right to the style of King, he replied: “My father was King; his father also was King; I myself have worn the crown forty years from my cradle; you have all sworn fealty to me as your sovereign, and your fathers have done the like to mine. How, then, can my right be disputed?” “By force,” they might have replied.

Queen Margaret, an infinitely more masculine being than the poor weak King, her husband, would not give up the struggle, and even after the Battle of Towton had destroyed the cause of her house, she raised its standard in the North. Warwick crushed her army, and after the Battle of Hexham in 1471, Margaret was forced to flee with her son. She is traditionally said to have owed her escape to a robber, on whose generosity she had thrown herself. Henry, meanwhile, was led a prisoner to the Tower, being treated, by Warwick’s orders, with every indignity. His gilt spurs were struck off when he reached the fortress, and his legs tied to the stirrups of his horse, which was led round a tree in front of the Tower which then served the purpose of a pillory. Once inside his prison the fallen monarch appears to have been treated with some kind of humanity, being allowed to see some of his friends, the use of his breviary, and the company of a favourite bird and dog. His prison was in the Wakefield Tower, and in one of the chambers—now containing the Regalia—was the oratory in which tradition has it that he was murdered by Gloucester.

Later on Queen Margaret and her daughter-in-law, Lady Anne Neville, were also imprisoned in the Tower, but the Queen never saw her husband again, for although they were in the same building they were rigorously kept apart. After an imprisonment of five years, part of which was passed at Windsor, Margaret was allowed to return to her own country, on the payment of a heavy ransom, where she died in 1482.

All through the Wars of the Roses the Tower had been the scene of some important events. When in 1460 the Earls of Warwick, Salisbury, and March arrived in London from Calais, Lord Scales was in command of the Tower. Scales was Lancastrian in his politics and sympathies, and after vainly attempting to keep the three Earls from entering the city, blockaded himself within the fortress; and it was only when the news of King Henry’s having been taken prisoner came to his knowledge that Lord Scales surrendered his trust into the hands of the Yorkists.

The new King’s coronation took place on St Peter’s Day, the 29th June 1461. Edward arrived from the Palace of Sheen at Richmond three days before the ceremony, and took up his quarters in the Tower, being received at the gates of the fortress with much pomp and state. On the eve of his coronation he gave a great feast to his adherents, knighting thirty-two of them. According to the chronicler Fabyan’s account, the new Knights of the Bath “were arrayed in blue gowns with hoods and tokens of white silk upon their shoulders,” and they rode before the King in the procession which took its course from the Tower to the Abbey at Westminster. Edward soon showed his vindictive nature by imprisoning, within the Tower, as soon as he felt himself secure upon the throne, Henry Percy, the son and heir of the Duke of Northumberland. Besides Percy, Aubrey de Vere, Earl of Oxford, with his heir, were also placed in the Tower in 1462, with some other nobles and knights who had fought upon the Lancastrian side; of these Sir Thomas Tudenham and Sir William Tyrell were beheaded on Tower Hill.

King Edward’s wife, Elizabeth Woodville, passed a few days in the Tower previous to her coronation in 1465, and both the King and Queen frequently lived in the Palace of the fortress, the Queen passing the time there when Edward was occupied in putting down an insurrection in the North.

When the whirligig of events and Warwick, the “King-maker,” brought back King Henry for a brief space of power, Elizabeth Woodville fled with her children to the Sanctuary at Westminster. The “King-maker” was defeated at the Battle of Barnet in 1471, and King Henry was brought back to the Tower once more a prisoner.

It was on Easter Sunday, in the year 1471, that Henry VI. re-entered the fortress for the last time. The fatal day of Tewkesbury was his doom, and Queen Margaret must be regarded as the cause of her luckless husband’s death. Could they have changed their rôles in life, Henry would probably have died on the throne and have left sons to succeed him. At Tewkesbury, Edward, who had left the Tower in charge of Earl Rivers, his Queen’s brother, again met Queen Margaret in arms, defeating her and taking her son prisoner. The death of this her only son, slain, it is said in cold blood, by the Duke of Gloucester, for whom she had waged unceasing war against the Yorkists, destroyed her last hopes. And on the 22nd of May 1471, the day after the triumphant Edward’s return to London, her husband lay dead in the Wakefield Tower.

The manner of his death will never be known, but the crime has always been charged to Gloucester. A great authority (S. R. Gardiner) thus writes of the death of the sixth Henry: “There can be no reasonable doubt that he was murdered, and that, too, by Edward’s directions.” Of the earliest histories relating to Henry’s death there are many and contradictory accounts. According to Polydore Vergil, Hall, Fabyan, Grafton, Holinshed, the Warkworth Chronicle, de Commines, and Sandford, King Henry was murdered by Gloucester himself. Hume alone avers that “he (the King) expired in confinement, but whether he died a natural death or a violent one is uncertain.”

Thus at length the much-tried and weary King Henry of Windsor was at rest after so many sore buffetings, defeats, perils, and misfortunes; his life’s pilgrimage was at an end.

“Good night, sweet Prince;

And flights of angels sing thee to thy rest.”

Henry’s corpse was taken, according to Holinshed, “unreverently from the Tower” to St Paul’s, where it remained one night, and was next day buried at Chertsey, “without priest or clerke, torch or taper, singing or saying.” In later times Henry’s remains were re-interred at St George’s, Windsor. On the pavement to the right of the choir in that burying-place of our English kings, a flagstone bears written upon it in large letters, “King Henry VI.”

We have now arrived at the most dramatic point in the history of the Tower. After Henry’s death a very host of bloody deeds took place within the walls of the gloomy old fortress; murder succeeds to murder; and the blood of princes seems to ooze from beneath its prison doors.

The next royal victim was the King’s brother, George, Duke of Clarence, “false, perjured Clarence.” For him, however, one feels little pity, since he well merited to be called both “false” and “perjured.” The old tale of his having been drowned in a barrel of Malmsey wine has been believed these four hundred years, and, as it cannot be disproved, it will serve as well as any other. It is the mystery which surrounds these murders committed in the dark towers of the old fortress, which adds not a little to their horror. An execution in broad daylight seems, compared with the unknown manner in which a prisoner was killed in some hole and corner of a dungeon, quite a cheerful event. One shudders at the thought of the helpless victim struggling in his death agony in the arms of his murderers.

Clarence’s death took place on the 18th of February 1478, but even the place of his imprisonment is unknown. By some he is said to have been confined in the Bowyer Tower; but in Mrs Hutchinson’s Memoir she has left on record that the Bloody Tower was the scene of his murder, and as she was the daughter of Sir Allen Apsley, the Lieutenant of the Tower in Charles the First’s reign, her authority on the matter is a good one. The only contemporary, or nearly contemporary writers, in favour of the story of the Malmsey butt are Fabyan and de Commines. The former, a London citizen, writes: “The Duke of Clarence was secretly put to death and drowned in a butt of Malmsay within the Tower.” Philip de Commines considered this to be a true version of the manner of the Duke’s death. It has been suggested that Clarence was poisoned.

Edward IV., as has been said, lived a great deal in the Tower; he also increased its fortifications, and, according to Stowe’s “Survey of London,” built “a brick wall around a piece of ground on Tower Hill west from the Lion’s Tower, now called the Bulwark.” This fortification has long ago disappeared. Edward likewise, according to the same excellent authority, renewed the moat and made considerable general repairs to the buildings. He was the last of our Kings who added materially to the Tower.

With the appointment of Richard, Duke of Gloucester, to the office of Protector, after the death of Edward the Fourth, on 9th April 1483, the Tower plays a conspicuous part in the events which the next few years produced. Edward had left two sons; the elder, now Edward V., being twelve years old, his brother, Richard, Duke of York, being a year or two younger. Gloucester had the reputation of being an excellent soldier, and had not, as was the case with his brother Clarence, been disloyal to the late King. Whether he was hump-backed or whether, as some writers aver, he was scarcely less handsome than his handsome brothers, or whether one of his shoulders was higher than the other, is not of much consequence; for whether he was crooked or not in person, Gloucester was certainly crooked in character. If any faith can be put in the lineaments and expression of the human face, that of Richard, to judge by the portraits that have come down to us, was most evil. His face can be studied in the National Portrait Gallery. The close-set cruel eyes, the heavy nose, the thin white lips, the protruding jaw, are not inviting; but the expression is even more remarkable—a mixture of cunning, boundless determination, and remorseless cruelty. Gloucester possessed, writes Mr Gardiner, “a rare power of winning popular sympathy, and was most liked in Yorkshire, where he was best known. He had, however, grown up in a cruel and unscrupulous age, and had no more hesitation in clearing his way by slaughter than Edward IV. or Margaret of Anjou.” Mr Gardiner is almost apologetic for Richard’s memory; but there is a great difference, it seems to me, between being revengeful and even merciless in war, and in murdering either with one’s own hands or by those of hired assassins, one’s brother and one’s nephews. It was by shedding their blood that Richard was enabled to mount the throne which he usurped: of that there is no room for any reasonable doubt. That Shakespeare, in giving the worst character of any in his great series of historical plays to this monarch, is responsible for the popular opinion of King Richard is also indisputable, for we English take our history from these plays, and “crook-back’d” Richard will ever remain the deepest-dyed villain that ever wore the English crown. The great Duke of Marlborough confessed that all that he knew of English history had been learnt through Shakespeare’s plays, and with all truth the majority of his countrymen might say the same. It has also been said, “The youth of England take their theology from Milton and their history from Shakespeare”; and surely they might go further and fare worse.

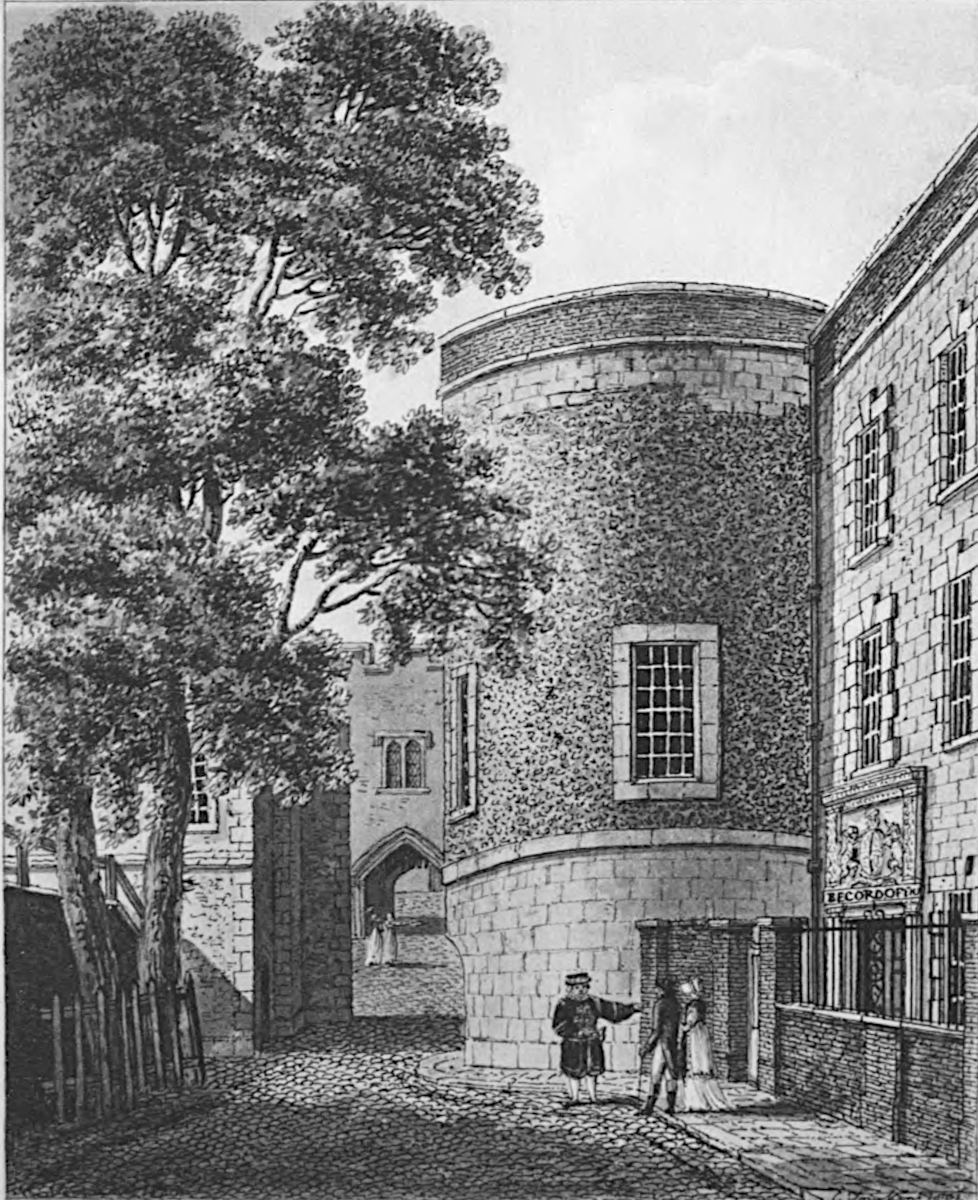

View in the Inner Ward

It should, however, in fairness both to Richard and to Shakespeare, be remembered that the character of the Royal villain in the play was drawn by one who wrote in the days of the Tudors, and at a time when the house of Plantagenet was not in good odour with the reigning Sovereign. Richard appears in three of the dramas—in the second and third parts of King Henry VI., and as the hero or chief villain in that which bears his name when King: the important part played by the Tower in the usurper’s reign is strongly marked by the poet placing four scenes of Richard III. within or near the fortress—twice as many as occur in any other of his historical dramas.

On the 13th of June 1483, Richard had the Archbishop of York, and Morton, the Bishop of Ely, together with Lord Stanley and Lord Hastings, arrested during a Council which he had summoned in the White Tower. Without any pretence of a trial, Hastings was led out of the Council Room by the soldiery whom Richard had concealed behind the arras, and, according to Fabyan, his head was struck off on a piece of timber which lay near St Peter’s Chapel. “I will not dine till they have brought me your head,” said Richard to Hastings, as he was being led away. The three other prisoners were placed in separate dungeons, the Archbishop and Stanley being released in the following July. Another victim was required by Richard. Lord Rivers, the late King’s brother-in-law, like Hastings, had been a check upon Richard’s designs for seizing the crown, therefore Rivers was executed, as was also Sir Richard Grey. There only now remained Gloucester’s two nephews between him and the throne. At this particular time they were living with their mother, the Queen, Elizabeth Woodville, at Westminster, and it was only by the strongest persuasion, followed by threats, that the unfortunate Queen was induced to allow their uncle to take charge of them. Gloucester, having first placed the Princes in the Tower, declared them to be bastards, and as Clarence’s children were prevented by their father’s attainder from coming into the succession, Richard openly declared himself the rightful King. He even went to the length of getting a preacher named Shaw to declare to the people that he alone was the legitimate son of the Duke of York, and that his brothers, the late King and the Duke of Clarence, were not his father’s sons. Perhaps this attack on his mother’s good name was the most odious of the many infamous acts of which Richard III. was guilty. On the 25th of June 1483 Parliament declared Gloucester the lawful heir to the throne, and on the 6th of July he was crowned as Richard III. But during that summer rumours as to the death of the sons of Edward IV. began to be spread abroad, and the King’s name was linked with the report that they had met a violent death in the Bloody Tower.

In a wardrobe account for the year 1483 there is a long list of articles of dress delivered at the Tower for Richard’s coronation. Among the dresses mentioned, we find that Richard had ordered the following elaborate costume:—“To our said Soverayne Lord the King for his apparail the vigil afore the day of his most noble coronation, for to ride from his Towre of London, unto his Palays of Westminster, a doublet made of two yerds and a quarter and a half of blue clothe of gold, wrought with netts and pyne-apples, with a stomacher of the same, lined oon ell of Holland clothe, and oon ell of busk, instede of green cloth of gold, and a longe gown for to ryde in, made of eight yerds of p’pul velvet, furred with eight tymbres and a half and 13 bakks of ermyn, and 4 tymbres, 17 coombes of ermyns powdered with 3300 of powderings made of boggy shanks, and a payre of short spurs with gilt.” To describe these queerly named habits of “apparail,” such as “tymbres,” and “bakks of ermyn,” and “boggy shanks,” would require the knowledge of an antiquarian deeply versed in the costume of the Middle Ages, but this account of Richard III.’s coronation outfit proves that he, at any rate, spared no expense in the decoration of his person, whether that was deformed or not.

His coronation was one of the most splendid on record up to that period in the annals of the English sovereignty. From the Tower to the Abbey he was followed by a cortege in which rode three dukes, nine earls, and twenty-two barons, besides a host of knights and esquires, all gorgeously arrayed. After the coronation festivities were ended, Richard went to Warwick, leaving the Tower of London in the charge of Sir Robert Brackenbury. Richard is supposed to have sent Sir Robert a message, which he received whilst attending mass in the chapel of the White Tower, asking him whether he would be willing to rid the King of the Princes. Brackenbury indignantly refused to have anything to do with such villainy, whereupon Richard relieved him of his charge of the Tower, and handed it over to James Tyrell, who hired the three murderers—Dighton, Green, and Forrest—these being admitted into the prison of the Princes in the Bloody Tower at night, when the double murder was accomplished. In describing the Bloody Tower, I have given an account of the place where this deed was done and the passage through which the murderers entered the prison.

The murderers were well rewarded—Richard Tyrell being appointed Governor of the town of Guisnes near Calais, also being given lands in Wales; Green obtained the Receivership of the Isle of Wight; Forrest’s widow (so probably Forrest died soon after the crime) received a pension. Further, in order to protect all those who were concerned in the affair, Richard issued under his royal hand and seal a general pardon for all their former offences.

The innocent blood was, however, avenged in the following reign. In 1502 Tyrell was beheaded, not on the charge of murdering the Princes, but for aiding John de la Pole to make his escape; this John de la Pole was Richard’s nephew, upon whom he had settled the succession after his own death. Tyrell, it is said, confessed to the murder of the little Princes shortly before his execution. Dighton, who was hanged at Calais shortly after Tyrell’s execution, also confessed his share in the murder, and his knowledge of the bodies of the children having first been buried by a priest near the Wakefield Tower, and subsequently in some other place unknown to him.

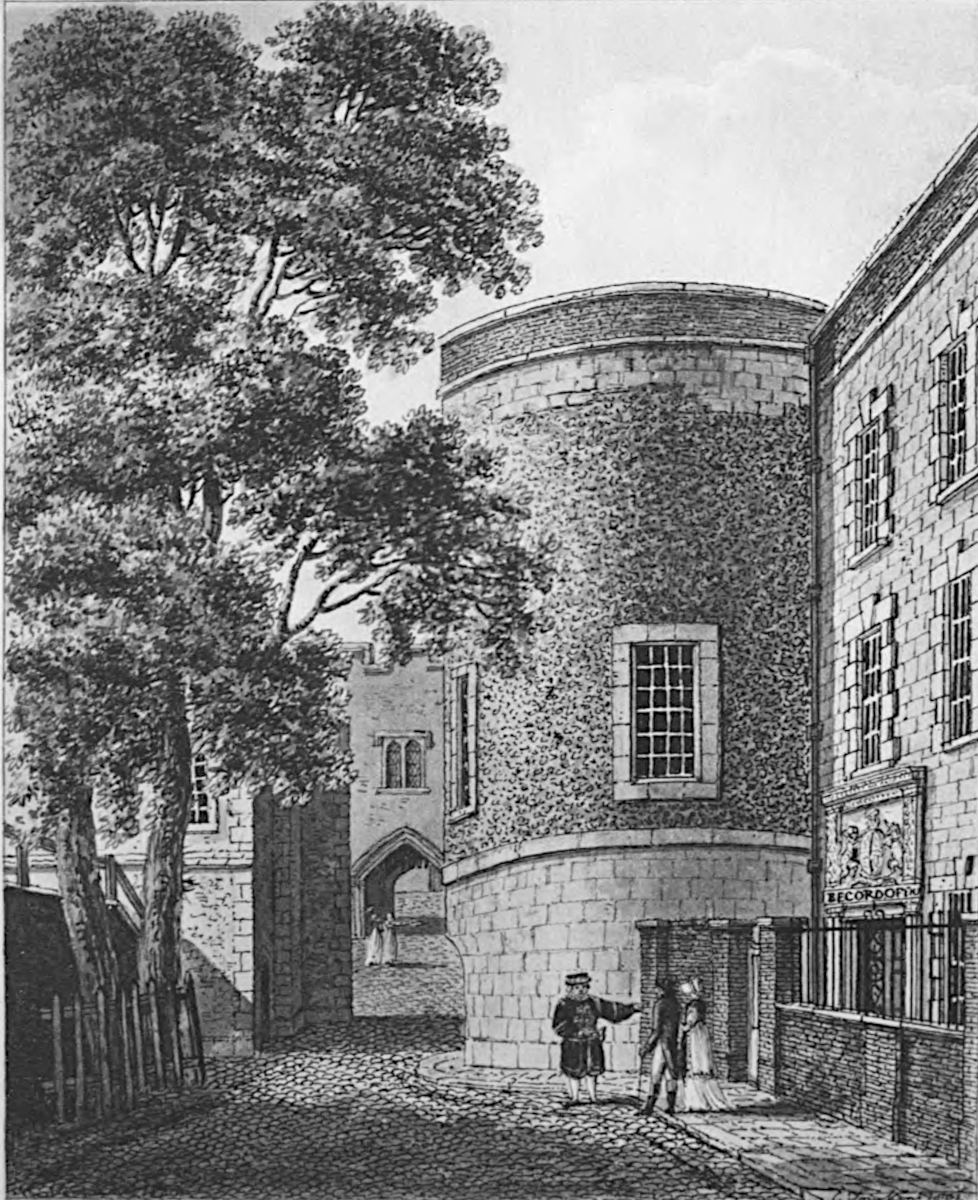

The Wakefield Tower, time of George III.

The earliest historian who wrote an account of this double murder was the French chronicler, Philip de Commines, a contemporary of Richard III. In his Chronicles occurs this passage relating to the King: “il fist mourir ses deux nepheux, et se fist roy appellé Richard III.” Two contemporary English authors have also written to the same effect. The first of these is a Londoner named Arnold, who, in his “Chronicles of the Customs of London,” states that in the year 1484 “the two sons of Kynge Edward were put to silence.” The second is Fabyan, from whom I have already quoted in these pages. He writes, “Kynge Edward V., and his broder the Duke of York, were put under suer Kepynge within the Tower, in such wyse that they never came abrode after,” and he adds, “common fame went that Kynge Richard hadde within the Tower put unto secrete deth the two sons of his broder Edward the IV.” Sir Thomas More, in a history which he did not write himself, for it was written by Morton, the Bishop of Ely, but which More published, also asserts as a fact that the Princes were murdered. Polydore Vergil, Hall, Stowe, and Bacon have all written to similar effect.

Horace Walpole amused himself—much in the same way as did Archbishop Whateley in later days—by writing a clever skit entitled, “Historic Doubts of the Life and Reign of King Richard III.,” in which that amusing and prolific writer of gossiping letters casts doubt on the very existence of such a being as King Richard III., which, if proven, would do away with the existence of the little Princes. But I imagine that “Horry” had as firm a belief that the Princes were destroyed by their uncle in the Tower, as the Archbishop had in the existence of Napoleon.

The tragic death of the sons of the fourth Edward has been a favourite subject both with poets and painters. Two of Paul de la Roche’s finest paintings represent the brothers in the Tower, and one of Millais’ most successful and characteristic works is a group of the two boy princes standing together on the prison stairs, and seeming to listen for their murderers’ approach. And who does not recall, when thinking of that tragedy, the matchless pathos of the lines describing the scene as spoken by Tyrell in Richard III.:

“The tyrannous and bloody act is done:

The most arch deed of piteous massacre,

That ever yet this land was guilty of.

Dighton and Forrest, whom I did suborn

To do this piece of ruthless butchery,

Albeit they were flesh’d villains, bloody dogs,

Melting with tenderness and mild compassion,

Wept like two children, in their death’s sad story.

O thus, quoth Dighton, lay the gentle babes,—

Thus, thus, quoth Forrest, girdling one another

Within their alabaster innocent arms:—

Their lips were four red roses on a stalk,

Which, in their summer beauty, kissed each other.

A book of prayers on their pillow lay;

Which once, quoth Forrest, almost changed my mind;

But, O, the devil—then the villain stopp’d;

When Dighton thus told on,—We smothered

The most replenished and sweet work of nature,

That from the prime creation, e’er she fram’d.

Hence both are gone with conscience and remorse,

That could not speak; and so I left them both,

To bear the tidings to the bloody King.”

A curious event occurred to one of the State prisoners in this reign, Sir Henry Wyatt—the father of the poet, Sir Thomas Wyatt, and grandfather of the Thomas Wyatt who lost his life for the part he played in the rebellion against Mary in favour of Jane Grey—was a Lancastrian in politics, and had been imprisoned in the fortress on more than one occasion; “once,” the Wyatt papers say, “in a cold and narrow tower, where he had neither bed to lie on, nor meat for his mouth. He had starved then, had not God, who sent a crow to feed his prophet, sent this and his country’s martyr a cat both to feed and warm him. It was his own relation unto them from whom I had it. A cat came one day down into the dungeon unto him, and, as it were, offered herself unto him. He was glad of her, laid her on his bosom to warm him, and, by making much of her, won her love. After this she would come every day unto him divers times, and when she could get one, bring him a pigeon. He complained to his keeper of his cold and short fare. The answer was, ‘he durst not better it.’ ‘But,’ said Sir Henry, ‘if I can provide any, will you promise to dress it for me?’ ‘I may well enough,’ said the keeper, ‘you are safe for that matter’; and being urged again, promised him, and kept his promise; dressed for him, from time to time, such pigeons as his acater the cat provided for him. Sir Henry Wyatt, in his prosperity, for this would ever make much of cats, as other men will of their spaniels or their hounds; and perhaps you shall not find his picture any where, but like Sir Christopher Hatton, with his dog, with a cat beside him.”

Prison beneath the Wakefield Tower.

Sir Henry had the faithful cat portrayed with a pigeon in its claws offering it through the grated bars of his prison window. There is a similar story of a cat befriending Lord Southampton when a prisoner in the Tower in the reign of Elizabeth.