CHAPTER I

THE BUILDINGS

NOTHING has come down to us of any authentic value regarding ancient London until Tacitus writes of Londinium as a place celebrated for the numbers of its merchants and the confluence of traffic. In the days of the Roman occupation St Albans, then called Verolanium, was a far more important place than Roman Londinium; and, perhaps, it was Verolanium whereto Cæsar marched in his second descent on Britain in B.C. 54, and which he described as a place “protected by woods and marshes.” Such a description would equally apply to Londinium, and, for aught we can know to the contrary, the town Cæsar describes as being surrounded by woods and marshes may have been our capital.

To the north of Roman London stretched vast primeval forests, and where St John’s Wood now stands, the wild boar roamed in trackless thickets. Marshes lay to the west and south, on the sites of Westminster and Southwark; a less likely place for the situation of a great capital, with the exception of St Petersburg, could not be found in Europe. On what is now Tower Hill stood a Celtic fortress, protected by the Thames on the south, and by forests and fens on the north. This fortress was admirably placed, protecting the approach from the seaward side of the river, and guarding against any attack from the land side. The Romans were evidently of this opinion, for after conquering the woad-stained Britons, they erected a fortalice, defended by strongly fortified walls, upon the same site.

This Roman fortress was the origin of the Tower of London.

Roman London, or rather Augusta, for so it was originally termed by the Romans, began at a fort named the Arx Palatina, overlooking the river a little to the south of Ludgate, a wall defended by towers, running in a south-easterly line along the river bank to another fort on the present site of the Tower, which was also named the Arx Palatina. Thence the wall took a northerly direction, reaching as far as the present Bishopsgate; it then turned due west to Cripplegate; then south by Aldersgate to Newgate, meeting the first wall at Ludgate. Roman London was indebted to the Emperor Constantine for these defences.[1]

Theodosius is supposed to have restored this wall in the reign of Valentinian, but we have no further records of any work upon it until A.D. 886, when Alfred the Great repaired it as a protection against the Danish invaders.[2]

The late Sir Walter Besant is my authority for saying “that there is a large piece of the Roman wall, extending 150 feet long, built over by stores and warehouses immediately north of the Tower, just where the old postern used to be, and where the wall abutted on the Tower.” It should be remembered, when judging of the circumference of the Roman wall, that London covered little more ground in those days than does Hyde Park at present: from Ludgate to the Tower the Roman wall extended only about a mile in length, and three and a half miles from the Tower to Blackfriars.

There are many fragments of this old Roman wall still above ground, and until 1763 a square Roman tower, built of alternate layers of large square stones with bands of red tiles, one of the three that guarded the wall, was still standing in Houndsditch. In 1857 a portion of the Roman wall was discovered near Aldermanbury postern, whilst a portion of a Roman bastion is still to be seen at St Giles’s Church, Cripplegate; another fragment being visible in a street called London Wall Street. There are more Roman remains at the Old Bailey and near George Street, Tower Hill. Fragments are also visible near Falcon Lane, Bush Lane, Scott’s Yard in Cornhill, and in underground warehouses and cellars near the Tower. In the Minories there are yet more remains of this ancient Roman wall. In Thames Street, oaken piles, which were the foundation of the wall, have been discovered. They supported a layer of chalk and stone courses, upon which rested large slabs of sandstone cemented with a mixture of lime, sand, and powdered tiles. The upper part of the wall was coated with flint, and this again was strengthened by rows of tiles.

The most interesting of these remains, however, is in the Tower itself—a fragment of the Roman fort or Arx Palatina (the place of strength), which was laid bare some few years ago when some buildings abutting on the White Tower were removed. It is built of the same materials as the fragments of the Roman wall, and shows that William the Conqueror not only erected the most formidable fortress in his newly-conquered country upon the site chosen by the Romans, but that he also incorporated the remains of their handiwork in his building. Whether Alfred the Great restored the Arx Palatina as well as the wall we do not know, but even if the fort were ruined, the fragment now at the base of the White Tower would have shown the Conqueror the value and importance of its defensive position, protecting as it did the eastern end of the city, and guarding the seaward entrance of the Thames. William’s site, however, covered part of the land belonging to the ancient boundary of the Roman occupation, and to provide the necessary space he pulled down a large portion of the Roman wall between the spot where the White Tower now stands and the river front of the fortress.

In the days of our first Norman kings, a single square tower or keep, usually situated on a hill surrounded by an artificial ditch or moat, was considered sufficient protection. One might give a long list of such towers or keeps both in England and Normandy, for William the First, not content with overawing the Londoners with his great tower in their city, built others at Dover and at Exeter, at Nottingham and at York, at Lincoln and at Durham, at Cambridge and at Huntingdon. Under Duke Rollo and his immediate successors the Normans built their fortresses by the side of navigable rivers, on islands, or near the sea, since these fortresses were not merely destined as defences, but also for places of safety. They were, in fact, places of refuge for the people of the surrounding country, who fled to them with all their possessions, and particularly their live stock, at the approach of an enemy. By their situation, safety, if necessary, could be obtained by taking flight on the neighbouring river or sea.

In Normandy—at Fécamp, at Eu, at Bayeux, at Jumiége, and at Oisel, to name but a few of these Norman keeps—this custom obtained. At Rouen, as in London, the principal fortress built by the Norman duke stood by the riverside, and not on the hills at the back of the town. None of these places mentioned above were stronger or more imposing than the great Norman keep in London, known for centuries as the White Tower, receiving that title at first, probably from the whiteness of its stone, and in later times from the continued coatings of whitewash which it received. Of the many castles in Normandy and Touraine of the same period as the White Tower, that of Loches resembles it most nearly in size and form. Loches is now almost a ruin, as are most of the Conqueror’s castles, but the great White Tower remains intact despite the storms, sieges, and fires through which it has passed during eight centuries. It is still the Arx Palatina of London and of the British Empire.

Although in situation the Tower cannot compare with such grandly-placed castles as Dover or Bamborough, Conway or Carnarvon, or vie in beauty of scenery with Warwick or Windsor, it remains the most historic building in our land; not even the mausoleum fortress of Hadrian in old Rome can compete in interest with the Norman fortress—palace—and State prison of London; Edinburgh Castle alone approaches it as regards its influence on the history of the capital it defended, for the northern fortress was also the home of its national sovereigns for centuries, its country’s chief prison, the store-house of its regalia, and its city’s strong place of defence; and, like the Tower, it has been guarded from its foundation up to the present time without a break, by its country’s armed defenders.

Every part of the Tower of London is pregnant with history and tradition. The proudest names of England—Howard and Percy, Arundel and Beauchamp, Stafford and Devereux—gain added interest from their association with the Tower and its story. Above all, it is for ever honoured as having been the last home of Eliot, of Russell, and of Sidney; it has been sanctified by More and Fisher, “Martyrs,” as a writer on the Tower has well said, “for the ancient, as also was Anne Askew for the purer faith.” And to Anne Askew’s name I would add that of Sir John Oldcastle, Lord Cobham, one of the first and noblest of English martyrs.

When William lay dying in the Priory of Saint Gervais, near Rouen, in the summer of 1087, the Great White Tower which he had built in London had been in existence for some ten years. Probably only that tower was then completed, with the great ballium wall between the Keep and the river. Stowe, the earliest English writer on antiquarian subjects, writing in Queen Elizabeth’s reign, has told us in his priceless “Survey of London,” that the White Tower was completed in 1078. Its architect, Bishop Gundulf of Rochester, was not consecrated until 1077, and was then occupied in building Rochester Cathedral and a portion of Rochester Castle; the keep, which still rears its ruined walls over Rochester and the Medway, was not built until a century later. In Mr G. J. Clarke’s work on “Mediæval Military Architecture”—a work as important to students of English architecture of the Middle Ages as is that of Viollet le Duc to French architecture—we are told that Gundulf died about the year 1108, at the good old age of eighty-four, in the reign of the first Henry. Possibly the Palace at the Tower and even the Wakefield Tower had been commenced by Gundulf, as well as some buildings of the inner ward, but this is uncertain. These buildings would include the great curtain wall extending from the Wakefield Tower to the Broad Arrow Tower, and the cross wall of the Wardrobe Gallery, and the building known as Coldharbour, these being the buildings which formed the nucleus of the palace of the Norman kings.

The Wardrobe, the Lanthorn, and Coldharbour Towers have perished; the Lanthorn Tower has been rebuilt. In 1091, according to Stowe, the White Tower was, “by tempest and wind sore shaken,” so much so that it had to be repaired by William Rufus and Henry I. In the same year that Rufus built the Great Hall at Westminster he surrounded the Tower with a wall, causing his subjects much discontent thereby, especially as he forced them to work at these defences.

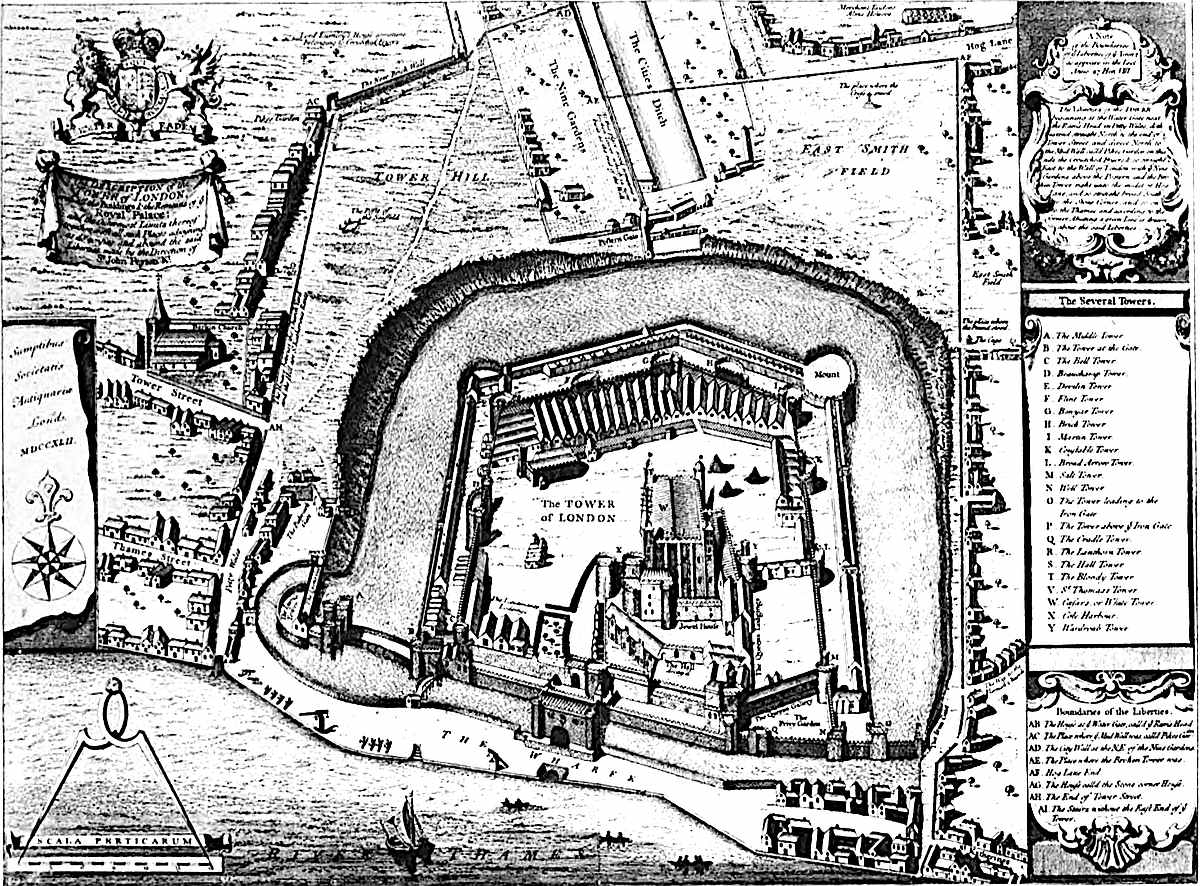

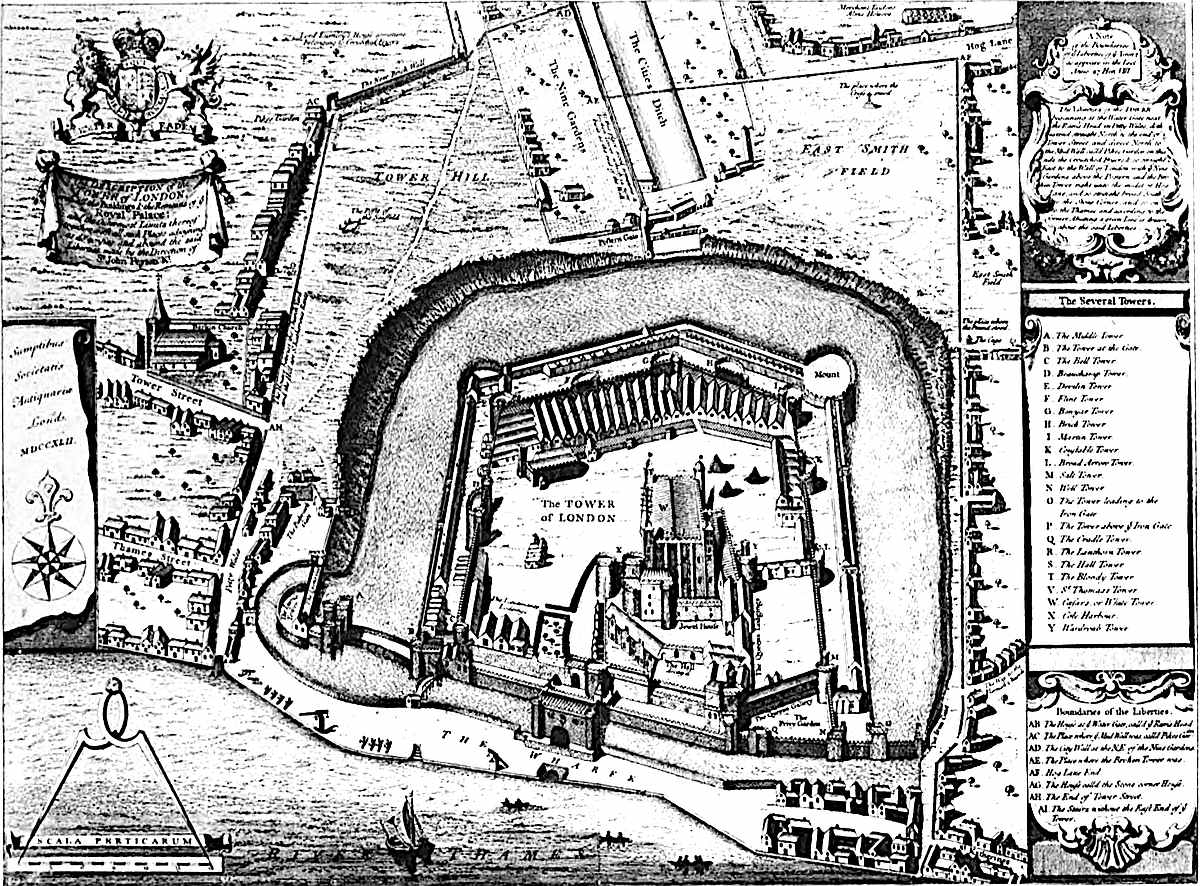

Sir Walter Besant recommended—and no one spoke with higher authority on aught appertaining to old London and its history—any one who desires to make himself acquainted with the appearance of the Tower in the days of Queen Elizabeth, to study the plan drawn up by Haiward and Gascoigne in 1597, which they styled “A True and Exact Draught of the Tower Liberties.” In that plan it will be seen at a glance that the fortress, palace, armoury, arsenal, and State prison of England’s capital, had its principal entry towards the west—in fact, that the western approach was the only entrance by land, the eastern entrance, known as the Iron Gate, being but seldom used. Supposing that the visitor of Elizabeth’s day had passed through the no longer existing Bulwark Gate, he would next pass under another gate, called from its proximity to the menagerie of wild animals, the Lion Gate, which was connected by a walled causeway over the moat, about a hundred feet in width, with the Lion Tower, which has disappeared; from the Lion Gate, which has also been pulled down, the scarp would be reached.

Plan of the Tower in 1597

by Haiward and Gascoyne.

The Lion Tower, with its barbicans and tête-du-pont, had the honour of a moat to itself, but all this has disappeared, Lion Gate, tower, barbican, tête-du-pont, have all vanished with the lions and other wild beasts which were kept here from the days of the Norman kings until the year 1834, when they were removed to Regent’s Park and formed the nucleus of the Zoological Gardens.

Henry I. had kept some lions and leopards at his palace of Woodstock, and on the occasion of Frederic II. of Germany sending three leopards to Henry III., these animals were sent to the Tower. Besides lions and leopards, an elephant and a bear were also about that time in the Tower menagerie. In 1252 the Sheriffs of London were ordered to pay fourpence a day for the keep of the bear, and also to provide a muzzle and chain for Bruin while he caught fish in the Thames. During the reign of the three first Edwards, the lions and other animals had food given them to the value of sixpence a day, their keeper only receiving three half-pence per diem. One of the Plantagenet Court officials held the office, and was styled “The Master of the King’s Bears and Apes.” In old views of the Tower can be seen the circular pit or pen in which, down to the days of James I., bear-baiting took place—to watch this brutal “sport” being one of this not altogether admirable monarch’s favourite amusements.

In his account of a visit paid to the Tower in the reign of Elizabeth, the German traveller, Paul Hentzner, writes of the Royal menagerie as follows:—

“On coming out of the Tower we were led to a small house close by, where are kept variety of creatures—viz. three lionesses, one lion of great size, called Edward VI., from his having been born in that reign; a tyger; a lynx; a wolf excessively old; this is a very scarce animal in England, so that their sheep and cattle stray about in great numbers, free from any dangers, though without anybody to keep them; there is besides, a porcupine, and an eagle. All these creatures are kept in a remote place, fitted up for the purpose with wooden lattices at the Queen’s expense.”

Hentzner, who visited England as tutor to a young German nobleman, gives a vivid account of what was considered most noteworthy in London in the days of Elizabeth, and in this the Tower looms large. His Journal was translated into English from the German and published by Horace Walpole, who had it printed at Strawberry Hill. We shall meet with Hentzner again in the White Tower.

Early in the eighteenth century there were eleven lions in the Tower, and in the Freeholder Addison alludes to the Tower menagerie; later on, Dr Johnson would growlingly inquire of newly-arrived Scotchmen in the metropolis, “Have you seen the lions?” In the place where formerly lions roared and bears were baited, the ticket office and visitors’ refreshment rooms now stand. In France or Germany here would probably be an attractive restaurant or café; but in these matters we English are woefully behind our neighbours, and it would be as difficult to find an appetising luncheon in the Tower as it is to understand why the art of cooking is so neglected in our country.

Near here, in 1843, when the moat of the fortress was drained of its waters and cleared of its rubbish, many stone cannon shot were found, shot which had probably been used when the Yorkists besieged the Tower in 1460 and cannonaded it from the other side of the Thames. In Elizabeth’s day this portion of the fortress was named the Bulwark or the Spur-yard—the origin of the latter term is not known.

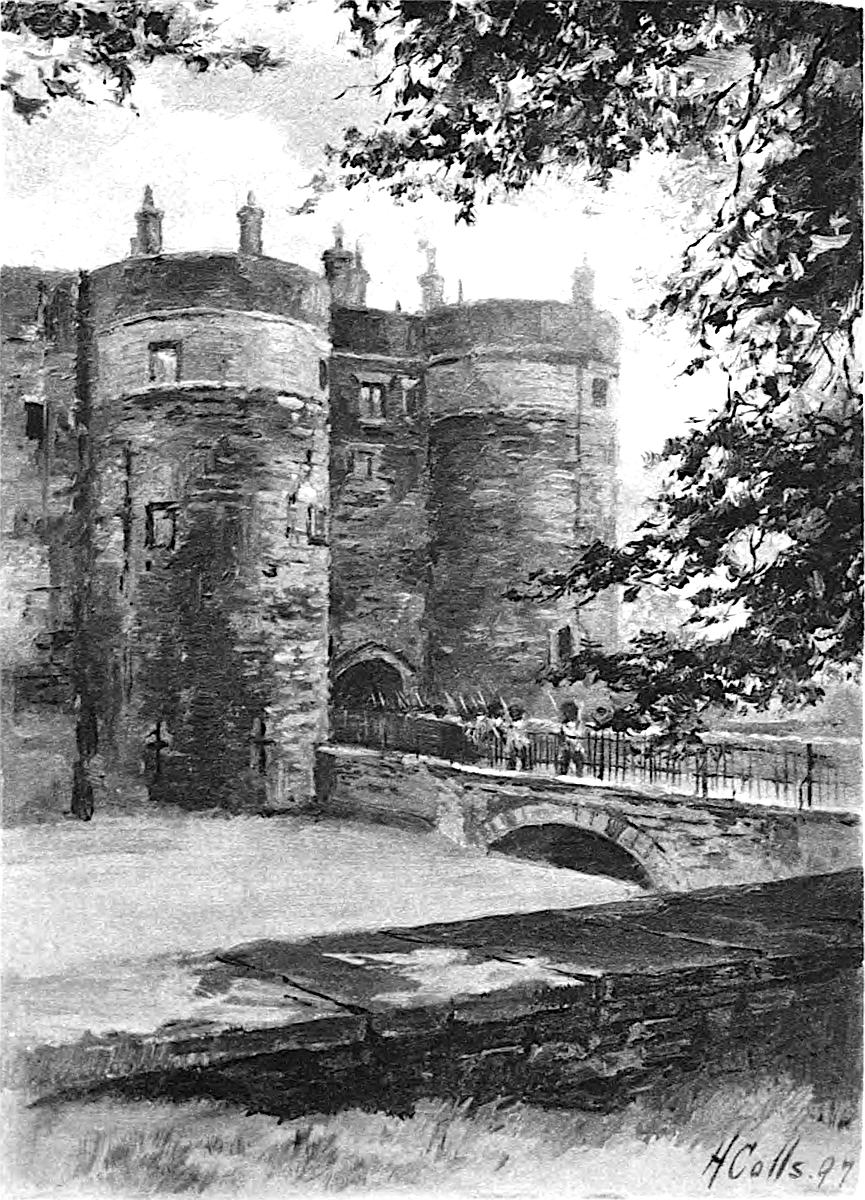

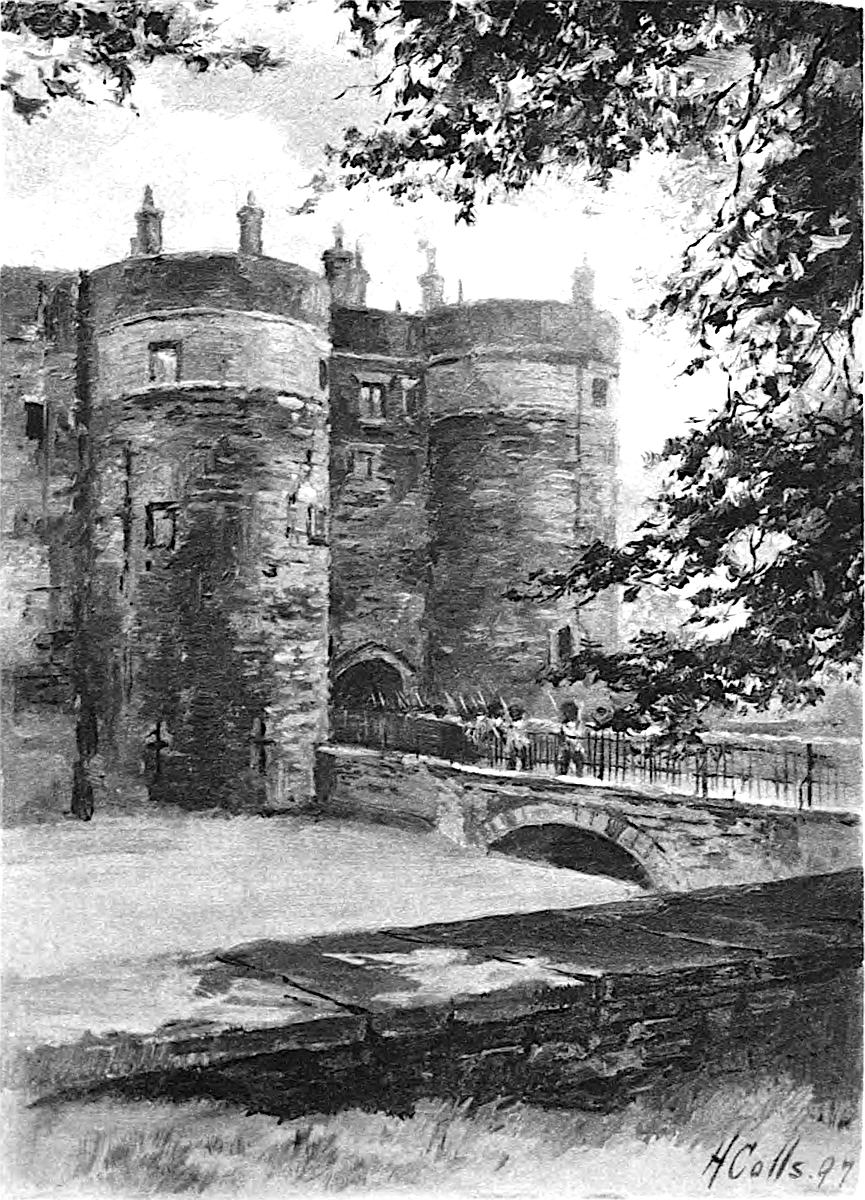

The Byward Tower.

The moat, some hundred feet wide at its widest, was formerly flooded with the waters of the Thames, and is now used as a parade and playground for the garrison. It dates back to the Norman Conquest, and was deepened by William Longchamp, Bishop of Ely in the reign of Richard I. Death was the penalty for bathing in its waters in the reign of Edward III.—a severe law, but one may hope that a sentence so severe for so apparently trivial an offence was not actually enforced; perhaps death was the result of some one having taken his bath in the Tower moat in the unsanitary days of Edward III. When the Duke of Wellington was Constable of the Tower, he had the moat filled up to its present level, and the river waters which had, daily, during eight centuries supplied it by their ebb and flow, ceased to encircle the old walls. Doubtless the fortress gained in healthiness by the change, but from a picturesque point of view the general effect of the building has been greatly lessened since the days when the old walls and bastions were reflected by the waters of the moat, nor can its towers and turrets appear so effective as when they were mirrored in surrounding water.

Four bridges with their causeways spanned the moat. To the west stood the Lion Gate bridge; a second was (and still is), that of the Middle Tower; the third faces the river at Traitor’s Gate under St Thomas’s Tower; and the fourth is that at the eastern extremity of the fortress, near to a dam which connected the tower above the Iron Gate with the tower formerly called Galleyman’s Tower, or “the tower leading to the Iron Gate.”

Middle Tower, the first by which the present visitor to the Tower enters the fortress, has been greatly modernised in its upper part. Since the destruction of the Lion Tower it has become the first gate of the Citadel, its name having been gained by its original position between the Lion and Byward Towers, to the latter of which it formed the outwork: it protects the western and landward approach to the fortress. Originally the Middle Tower was coated with Portland stone. It has a double portcullis, which can still be used if required. In front of this Tower, in mediæval days, stood a drawbridge, of which however, no trace remains, the moat now being spanned by a bridge of stone 130 feet in length and 20 feet in width at its narrowest part.

It was in front of this gateway that Elizabeth, on returning a Queen to the Tower, which she had left five years before a prisoner, alighted from her horse and kneeling on the ground returned thanks to God, “who had,” as Bishop Burnet writes in his “History of the Reformation,” “delivered her from a danger so imminent; and for an escape as miraculous as that of David.” To the right of the Middle Tower a road leads to Tower Wharf, from whence one of the most striking views in the whole of London is seen. Before the spectator stretches the famous “Pool,” that wide space of ever-shifting water on which rides all the shipping of the mighty river. It is a view which combines past and present; all the stir, the toil and traffic of the Thames lies before one, and for background rise the pinnacles, towers, and embattled walls of the grim old fortress, looking down on the ever-changing but time-defying stream.

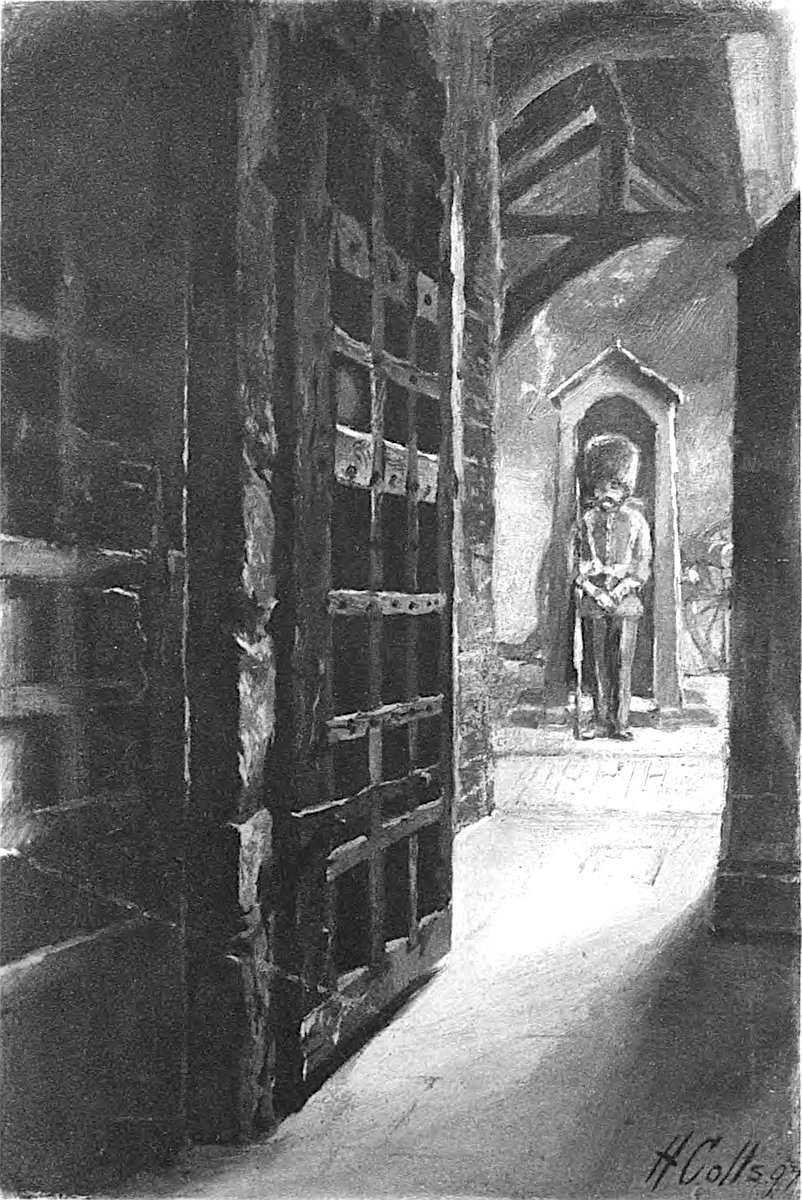

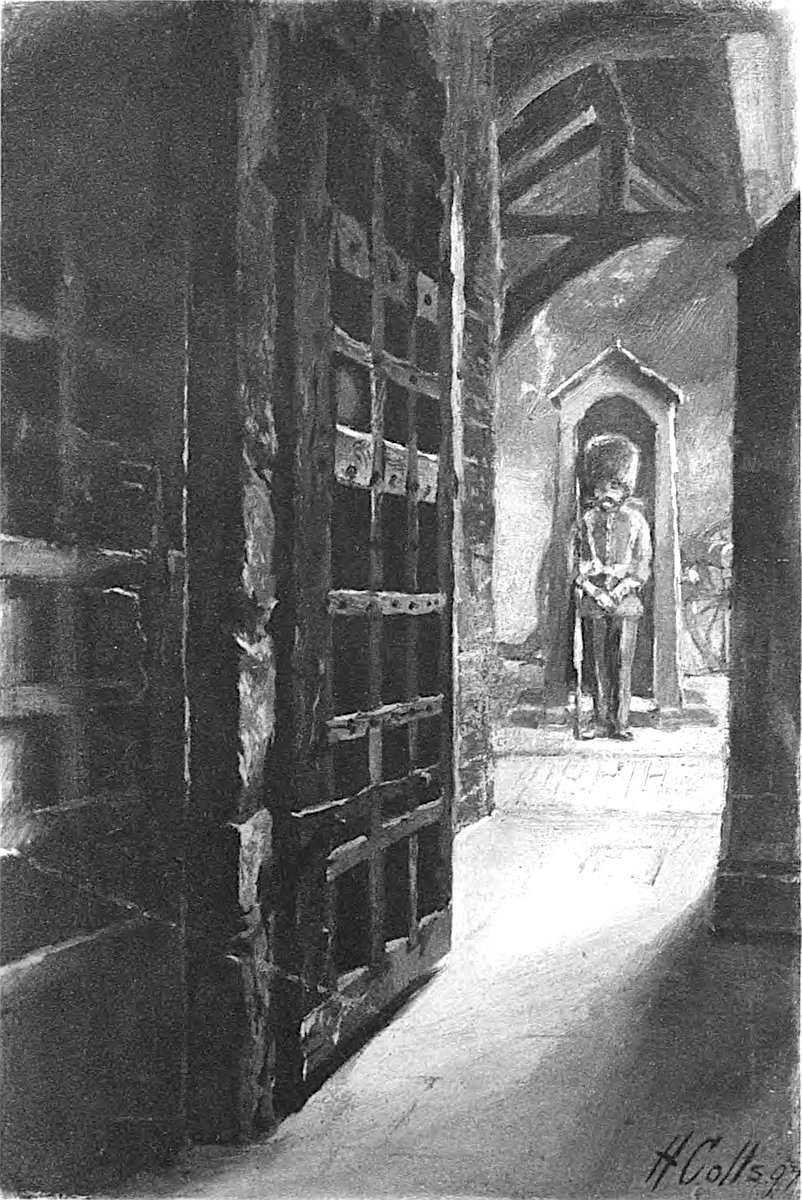

Returning to the Middle Tower, and passing along the causeway which spans the moat, the Byward Tower is reached. The Byward Tower forms the gatehouse of the Outer Ward of the Tower, and dates back to the reign of Richard II. In form this tower is rectangular, it has three floors, and rejoices in a portcullis which, like that of the Middle Tower, could still be worked. In the time of Henry VIII. the Byward Tower was known by the name of the Warding Gate. Upon the right-hand side of the entrance there is a fine vaulted chamber, some 15 feet in size, which is supposed to have been used as an oratory during the Middle Ages. It is now occupied by the Warders of the Tower, and is called the Warders’ Parlour; with its loopholed windows and ancient stone fireplace, it is one of the best preserved interior portions of the fortress. There is a corresponding chamber on the opposite side of the gateway. Attached to the Byward Tower, on its south-eastern side, is a low tower intended to protect the postern bridge which here crosses the moat towards the river side. It has an old oak door, half hidden by a sentry box, over which is a vaulted roof dating from the reign of Richard II., and this, with the narrow tortuous passage, forms a picturesque corner of the Tower buildings.

Postern Gate in the Byward Tower.

To mention the Warders of the Tower necessitates something more than a passing allusion to that most worthy body of veterans, since the Warders of the Tower of London belong to the most interesting of the old fortress’s institutions. Yeomen-Warders is the proper designation of the forty or so old soldiers who guard the Tower, who show and describe its different parts to visitors, and whose civility and patience are matters for the highest encomium. Originally these guardians were employed by the Lieutenant of the Tower to guard the prisoners committed to the State prison under his charge. But in the reign of Edward VI. the Duke of Somerset, after his liberation from the Tower, caused those warders who had had charge of his person during his imprisonment to be appointed, as a reward for their attention, extra Yeomen of the Guard. And from that period dates, with some modifications, the costume still worn by the Tower Yeomen. The Warders of the Tower are all picked men, and have all been appointed to their posts for good service in the Army. In the old days when the State trials were held at Westminster Hall the “Gentleman-Gaoler”—as that Warder was named whose affair it was to escort and guard the State prisoner to and from his trial, and who carried the processional axe (still kept in the Queen’s House) before the prisoner with the edge turned away from him on the journey to Westminster, and almost always with its edge towards him as he returned, as a sign that he was condemned to die—was the principal of the Tower Warders. The office is still maintained, inasmuch as he takes the front place on State occasions of ceremony, when the old axe is taken from its honoured repose in the Lieutenant’s study in the Queen’s House.

The Warders of the Tower must not, however, be confounded with the Yeomen of the Guard, the latter of whom are more usually known by the name of Beefeaters, and who, in their picturesque and striking uniform, make so effective a display on State occasions, such as the Levées at St James’s Palace, and State balls and concerts at Buckingham Palace. Whether the designation “Beefeater” originated from a supposed, but non-existent French word “buffetier” or not is a matter of no importance; but what is interesting is the fact that this body of men, with the exception of the Pope’s Swiss bodyguard, are the only set of attendants belonging to a European Court who retain a costume similar to that worn by their predecessors over three centuries ago.

Passing under the Byward Tower the Inner Ward is reached, into which entrance was gained from the river by Traitor’s Gate, the steps to that famous portal running below St Thomas’s Tower. Formerly cross walls, guarded with strong gates, defended the Inner Ward, but these have long since disappeared, together with the grated walls which shut in the passage across the Ward from Traitor’s Gate to the Bloody Tower.

As recently as the year 1867 this portion of the Inner Ward was covered with storehouses, engine-rooms and the lodgings of the warders, and most of these buildings, according to Lord de Ros, were in a state of total dilapidation, “the result of many years of neglect on the part of the former Board of Ordnance.” Since that time a great improvement has been made here, as well as in other parts of the fortress: of these improvements a list is given in the Appendix.

Yeoman Porter of the Tower.

Bounded by the Bloody and St Thomas’s Towers ran a narrow street called Mint Street, from the adjoining building occupied by the offices of the Mint, which consisted of a row of mean houses that hid and defaced the fine old Ballium wall of the fortress. Regarding this Ballium wall, Lord de Ros, in his account of the Tower, explains the word “Ballium” as “a military term,” but wishing for some further knowledge as to the meaning of the word, I referred to my learned friend Mr W. Peregrine Propert of St David’s, who informed me that it was probably derived from the French term “bailler,” meaning “to deliver possession, to lease, to hold, keep, contain.” The Latin form Ballium would accordingly mean something that is held, contained, or enclosed. Castles in ancient times were usually enclosed by several circuits of walls, fences, or ramparts. Sometimes there was a ditch or moat built outside these defences, as was the case in the Tower of London. The space between these walls was called the “Ballium.” On the site of the prison of Newgate stood a Roman fortress which was no doubt surrounded by ramparts, and the space so defended has retained its old appellation Ballium in the present term Old Bailey. “It is quite natural,” adds Mr Propert, “to suppose that if one wall disappeared the remaining wall would be called the ballium popularly: in the same manner a wall in the Tower of London might be called a Ballium, though not correctly according to its etymology.”

The Ballium wall at its highest is some forty feet high, and dates probably as far back as the Conquest; it is, therefore, one of the most ancient parts of the Tower, and coeval with the White Tower. It commences at the Main Gate of the outer rampart at the Bell Tower, and forms the angle of the Queen’s or Governor’s House, whence it runs for some fifty yards to the north-west until it joins the Beauchamp Tower: this tower forms a bastion near the centre of the Ballium wall. To the right the restored Tower of St Thomas overlaps the Traitor’s Gate. This tower dates back to the reign of Henry VIII., and was entirely rebuilt in 1866 by Salvin, only a portion of the interior retaining the walls of the original building.

Among a crowd of dingy wine-shops, offices, storehouses, and buildings which, according to good authority, were mostly “in a condition of ruin and dilapidation,” stood the old Mint, of which some account must here be given:

In the twenty-first annual account of the Deputy Master of the Mint for the year 1890 is the following account of the Mint when it was still within the Tower walls:—

“Among the old records of the Mint a discoloured parchment has been discovered, which is described as ‘An exact survey of the ground plot or plan of His Majesty’s Office of the Mint in the Tower of London.’ It bears the date February 26, 1700, and is of special interest as having presumably been prepared by order of Sir Isaac Newton, who was appointed Master of the Mint in 1699, having previously held the office of Warden.... The Mint buildings were situated between the rampart, which is bounded by the moat, and the inner ward or ballium of the fortress, which they entirely surrounded, except on the river frontage.... There are ample data as to the nature of the machinery and appliances which filled the various workrooms at the time when the plan was prepared. The more important machinery would be the rolling mills. The rolling mills were drawn by horsepower, and the rolls were of steel and of small dimensions. The coining presses were screw presses, and must have been the same as were introduced by Blondeau in 1661, under the direction of Sir W. Parkhurst and Sir Anthony St Ledger, Wardens of the Mint, at a cost of £1400. Blondeau, who greatly improved the system of coining, did not, however, invent the screw press, as Cellini described it accurately in 1568.”

The Wakefield and Bloody Towers.

In 1698 Sir Isaac Newton writes from the “Mint Office, October 22nd,” as follows:—“Sir, Pray let Mr James Roettier have the use of the great Crown Press in the Long Press Room for coyning of the Medalls, and let some person whom you can confide in, attend to see that Mr Roettier make no other use of the said press room than for coyning of medalls.—To Mr John Braint, Provost of the Moniers.”

Sir Isaac was evidently suspicious of the uses that Roettier might make of the Crown press, and not overconfident of the honesty of the old Dutch medallist. We shall have more to say regarding Roettier when describing the Tower under the Stuart king’s Restoration.

It is uncertain if Sir Isaac Newton occupied the house of the Master of the Mint in the Tower, although it is recorded in the Conduit MSS. that Halley once dined with Sir Isaac at the Mint. At the end of the seventeenth century and the beginning of the eighteenth, Newton had a house in Jermyn Street, St James’s. The lodgings in the Tower of the Master of the Mint were immediately to the north of the Byward Tower, whilst those of the Warden were to the left of the Brass Mount, on the north of the Jewel or Martin Tower.

The debasement of the coin of the realm, especially during the reigns of the Tudor Sovereigns, caused great loss to the State, the matter becoming so serious that Latimer denounced this criminal practice from St Paul’s Cross, Sir John Yorke being then Master of the Tower Mint. In 1550–51 it is recorded that there was “great loss, 4000 weight of silver, by treason of Englishmen, which he (Yorke) bought for provision for the minters. Also Judd, 1500; also Gresham, 500; so that the whole came to 4000 pound.” There is a letter to the Treasurer, dated 22nd August 1550, ordering him “to waie and cause to be molten downe into wedges all such crosses, images, and church and chapelle plate of Gould as remains in the Towere.” This letter was accompanied by a warrant signed by Henry VIII. for “VIJM pounds appointed to be delivered to Sir John Yorke for such purposes as his Lordship knoweth.” This act of spoliation of all the Church treasure in the Tower by the rapacious Henry, accounts for none of the plate in the Chapel of St Peter’s dating further back than the reign of Charles I.

The famous Traitor’s Gate is perhaps the most historic plot of ground in England, for here some of the noblest of our race have played the last scene but one of their lives. More tragic pathos attaches to this black water-gate than to the Bridge of Sighs in Venice; it is more deeply dyed with gloom than the glacis of Avignon, the dungeons of St Angelo, or the Austrian Spilberg. But a few steps had to be traversed by the prisoners, when landed at these steps, before they entered the Bloody Tower on the opposite side of the Ward, not to pass thence until the day of their execution. The Traitor’s Gate was the principal of the Barbicans or water-gates of the fortress; it commanded the passage between the Thames and the moat. The stone arch which spans Traitor’s Gate springs from two octagonal piers, and is 61 feet across. On the old steps, that can still be traced below the modern stone stairs by which they are overlaid, many an illustrious victim landed from the barge, in which the prisoners of State were generally taken to and from their trial at Westminster.