CHAPTER VII

Elinor Benton’s worldly intuition that a crisis was imminent in her home, an inevitable clash with her mother in which one or the other would have to admit herself vanquished was not without foundation. Neither the girl nor her father were able to comprehend the mother’s attitude nor why she should herself be, or wish them to be so different from all those with whom they were in these days thrown in contact. Sixteen years of suppressing her emotions, of unsatisfied longings had made her incapable of showing her inner feelings, the tenderness that so passionately wished only for the good of those dear to her. From some remote ancestor she must have inherited the coldness and intolerance she showed outwardly, and which was to her husband and children their only criterion. Cold and hard outwardly, intolerant to the extreme of anything that did not agree with her puritanical convictions which the years of self-communing had made all but fanatical, Marjorie Benton did not, could not open her heart and plead with those she loved to understand her, to meet her half-way in her efforts to make them see all she wished was to stand for what was good, pure and true. A faulty reasoning, aided by that inherited stubbornness, had persuaded her her best source was to assert indomitable authority as wife and mother—to force her own to bend to her will, with no idea of the give and take that makes worlds go around smoothly. She had forgot to reason, too, that her children were her own, and had without doubt inherited some of that very stubbornness which so momentarily threatened the Benton ship with going on the rocks.

Elinor had felt—seen—the clash coming. But she had not expected it quite so soon after her confidential chat with her father.

The lateness of the hour—(it was past seven) when she arrived home from her afternoon at the matinée was the signal—the beginning of it all. Her father and mother had finished their dinner and were in the library, the father absorbed in his evening paper, but the mother sat with her hands idly clasped in her lap, her eyes never wandering from the clock in the corner until her daughter rushed in apologetically.

“Sorry to be so late,” she deplored. “I hope you haven’t waited dinner for me.”

“Your father and I have had our dinner.” Her mother seemed not to notice the breathless apology. “I have ordered yours kept warm for you.”

“Thanks, mother, you are very kind, but I can’t eat a mouthful. We had a rather sumptuous luncheon, and it was 6:30 when we finished having tea at the Waldorf.”

Marjorie walked across the room and pressed the bell. When the butler entered she ordered him to inform the cook that “Miss Elinor had already dined.” Then she turned and faced her daughter.

“It strikes me, Elinor,” she said slowly, “that for a young girl so recently introduced into society, you are assuming unwarranted privileges.”

Though he at first attempted to assume a neutral attitude and kept his eyes on his paper, Hugh Benton stirred uneasily, his very attitude showing that the scene he felt sure would ensue was most distasteful to him. He set his jaws at a belligerent angle. Well, if it must come——

Elinor Benton flushed dully at her mother’s words. Her glance sought her father, and what she saw there apparently gave her courage. With a calmness and coldness matching Marjorie’s own, and with her dainty chin tipped at a dangerously belligerent angle that showed her as much like one parent as the other, she faced her mother, and, as though addressing an insolent stranger, her answer came icily.

“I fail to understand you, mother,” was what she said. “As usual you are speaking enigmatically.”

“In that case I shall lose no time in making myself clear,” the mother began, but her words were cut short.

“I say,” Hugh interrupted hurriedly as he dropped his paper, and glanced up with a smile as though some remarkable idea had come to him. “How about you two dressing as quickly as you can and driving into town with me. We can make one of the Roof shows! Eh, what?”

Elinor clapped her hands delightedly.

“Fine, Dad!” was her enthusiastic acceptance. “It won’t take me five minutes to dress. I’m dying to attend a Roof revue—I hope you can get tickets.”

“In case I can’t, we will go over to ‘The Palais Royal,’ ” Hugh answered, with a man’s natural eagerness to avert the inevitable argument between Marjorie and Elinor.

“One moment, please,” Marjorie cold, wide-eyed, forbidding, addressed her husband. “Your attempt to silence me, Hugh, is obvious. Besides, you know perfectly well I never attend a Roof show, and I surely will not permit my daughter to do so.”

With a pertness she had not before considered when addressing her mother, the daughter exclaimed with a toss of her head:

“Well I can’t see why you should object if Dad proposes taking us!” Angry tears rushed to her eyes.

“I consider it unnecessary to state my reasons. It should be sufficient that I do object—most strenuously. There are a great many things that I wish to say to you, Elinor. This is probably an opportune time. Perhaps it would be better for you to come with me to my room.” Marjorie rose and started toward the door.

All signs of neutrality vanishing and with a sternness and a fire in his eyes his wife did not recognize, Hugh Benton threw down his paper and rose, too. He made his way to his daughter’s side.

“Elinor!” he said gently as he placed his arm about her. “Please go to your own room for awhile. I wish to speak with your mother, alone.”

“You just heard me request Elinor to come to my room?” Marjorie was astounded. “Surely you——”

“Elinor, do as I say,” Hugh repeated. His wife he ignored.

Marjorie’s glance at his white face and tightly compressed lips showed her a new Hugh. With an indifferent shrug of her shoulders she sat down to wait.

Frightened by what was occurring, Elinor’s arms went up to close about her father’s neck. Marjorie winced unconsciously as she saw the gesture. It proclaimed so plainly who her daughter believed to be her best friend—which one she loved.

“I’m sorry, Dad,” the girl stammered with a sob as she slowly left them.

Marjorie Benton’s eyebrows went up in disdain as the door closed behind Elinor and her husband came over to stand before her wordless, hands in pockets.

“I suppose,” she commented, bitterly, “you are greatly elated at having humiliated me before Elinor.”

“You know that is not true!” Hugh’s voice was tense as he gave his wife the lie for the first time in his life. He was thoroughly exasperated, out of patience with her and what he believed were her ideals. “I am only sure of one thing. You have got into the way of making a tragedy out of every little thing that does not suit you, and this is just another example. But if you are looking for tragedy, something real to dramatize over,” and his lips tightened into a grim line as he accentuated every word, “I just want to tell you that this time you may succeed beyond your wildest expectations!”

“Why, Hugh—what do you mean—I—” Marjorie’s voice was tremulous as she sought to understand what had brought this storm of her husband’s about her ears.

“I think this time you’ll have no cause to complain about not understanding what I mean. And for once, I expect you to listen to every word I say!”

There was no doubting the earnestness of Hugh Benton’s tone, or that he was wrought up to a pitch rarely known to his easy-going nature. For once, the cloak of her authority dropped from his wife’s shoulders and she shrank in her chair as her meek reply came.

“Very well—I’m listening. I suppose,” and there was a flicker of her sternness and sarcasm, “I may as well try to comprehend you and your very peculiar attitude——”

Hugh Benton flicked his cigarette into the wide fireplace, staring after it a moment before he turned to face his wife. With arms folded, he towered over her, his whole manner that of a stern, unyielding judge.

“Marjorie,” he began, “I realize that you are my wife, and as such, entitled to many privileges. But there is such a thing as carrying your prejudices too far. The way matters have been going on in this house for some time now simply cannot continue. Not only the children, but I, myself, have reached the limit of my endurance. We came to New York sixteen years ago at your suggestion, not mine. I always wish you to remember that. When I realized that your one ambition was for me to become a success in this great metropolis, I determined to use all my energies and capabilities to satisfy your desires. Financially and socially I believe I have reached your expectations. In everything else my life is a complete failure.”

“Failure?” Marjorie’s voice trembled as her face showed her genuine surprise.

Hugh nodded emphatically. “Yes, failure,” he emphasized. “My children love me, not for myself, but because I am able to gratify all of their whims and desires, and strange to say, I am perfectly willing to pay for their show of affection, because it is the only tie that binds me to my home.”

Tears of distress which in spite of her pride forced themselves to unwelcome eyes, trembled on Marjorie Benton’s eyelids and splashed down on the hands folded so quietly over her somber gray gown.

“Hugh!” she cried, distressed. “Surely you don’t know what you say! What about your wife?”

“You asked the same thing years ago, Marjorie,” Hugh answered bitterly, “when we discussed the advisability of coming to New York. You were all the world to me then, and——”

“And now I am nothing.” Marjorie’s quivering lips completed the sentence. “I—I understand, Hugh.”

“You are still the mother of my children, despite the fact that they are both disappointments to me.”

Hugh was calm in the face of his wife’s tragedy, but his very calmness gave back to his wife some of her fighting spirit.

“If they are disappointments to you, it is your own fault,” she flared. “You humor them beyond all reason. I try to enforce strict discipline, and you invariably interfere. This very evening when I attempted to reprimand Elinor, you resorted to almost childish subterfuge to prevent an argument.”

“I’ll tell you why I interfere.” Hugh was getting to the gist of his lecture. “It is for the simple reason that I consider you the real culprit. The children are not to blame because they are selfish, worldly, way beyond their age, and lacking in love and respect for their parents. You raised them both in schools and colleges where they were thrown in contact with the wrong companions. Had you kept your children with you and reared them in the environment of home and love, everything would have been different.”

“How like you to put the blame on me.” Marjorie’s lip curled in scorn, and her foot in its common sense high shoe tapped impatiently on the soft-toned rug. But Hugh Benton was in too deadly earnest to be switched from his main topic by a side remark. He went on, as though his wife had not spoken.

“And now, you expect a girl and boy, grown up, to obey you implicitly, and change in a few days the training they have received for years. I tell you, Marjorie, you are employing the wrong method. You must realize it is too late for you to command, and if you persist in continually arguing with Elinor, and criticising her every act, you will drive her to desperation, that’s all. She is a self-willed and headstrong girl, and it is necessary to handle her with caution and the utmost diplomacy.”

Marjorie could not forbear one bitter reminder. “As long as you find so much fault with your family, why don’t you devote less time to your club and try to remodel them?”

“If you were the kind of a wife I once believed you to be I shouldn’t have to find diversion at my club,” Hugh answered sadly. “But what do I ever find at home now, save criticism.”

“You really are a badly abused man, Hugh. First it is your children, and now your wife—I don’t see how you manage to bear up under your heavy burden.”

The tinge of sarcasm in Marjorie’s voice stung Hugh to the quick. His fist banged down on the table with rage.

“What is the use?” he exclaimed violently. “I may as well try to reason with an infant. We have been drifting further and further apart until we haven’t a single idea in common. Our lives together under this roof is a mockery, but up to now I have always remembered that you are my wife and have never as much as permitted myself to indulge in the thought of another woman; but from this moment I am through with conventionality. I am going to drift wherever the tide takes me. If you don’t care to be a wife to me, to interest yourself in at least some of my interests—I can’t find happiness in my own home, I shall seek it elsewhere!”

In his old manner of having said the last word on a subject, Hugh Benton jammed his hands in his pockets and stalked to the door. Marjorie heard him call out an order to have the limousine at the door in fifteen minutes. Then she looked up to see him standing with his hand on the door knob as he looked back into the room for one last word.

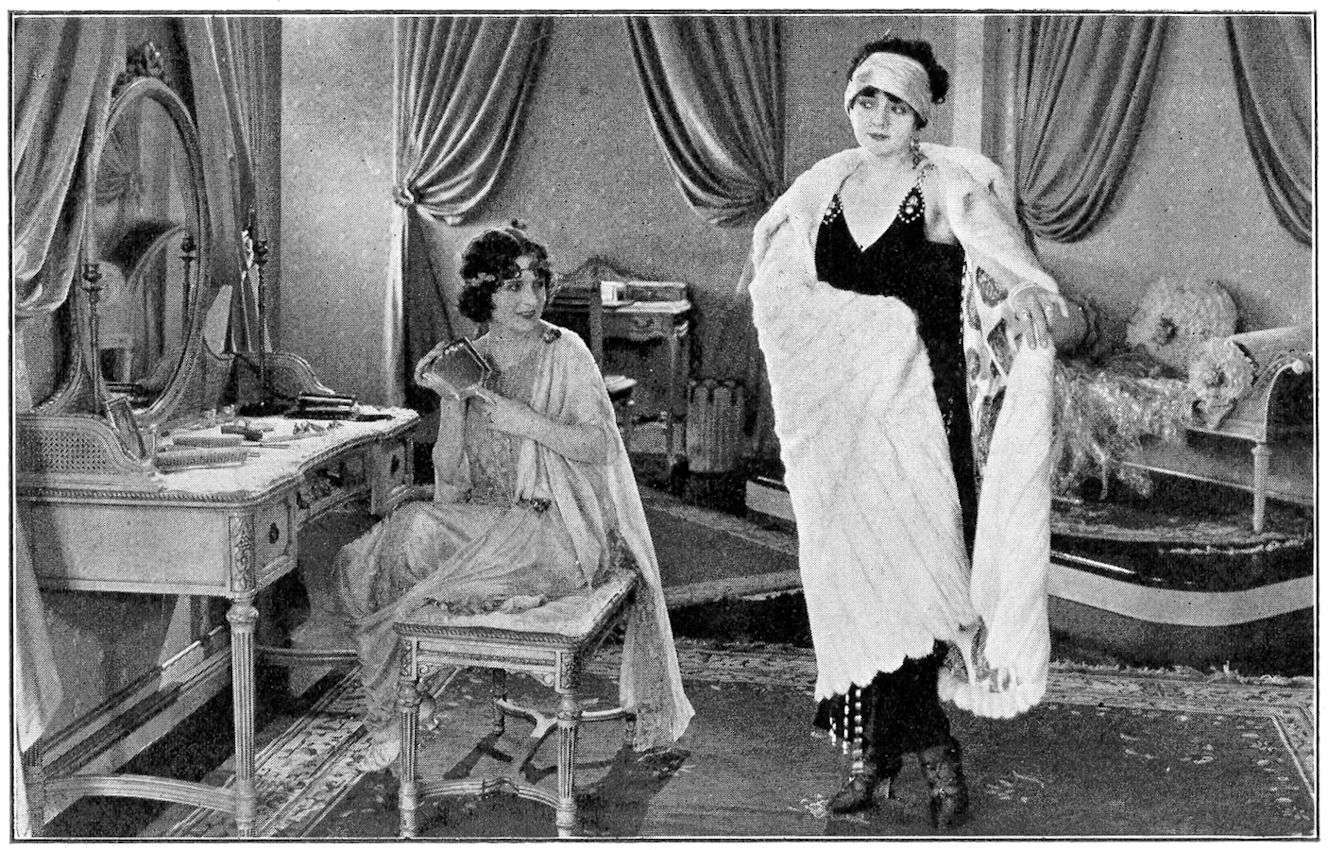

Elinor Benton realizes that Geraldine (Winifred Bryson) has stolen her father’s affection.

(“The Valley of Content” screened as “Pleasure Mad.”)

“And another thing!” He fairly bit off his words. “I understand you’ve decided to decline our invitation to the Thurston’s ball on the seventeenth through some foolish notion of not approving of some of their relations or guests. You are to accept at once—understand? I intend going and taking Elinor!”

Marjorie nodded dully—and with no other word he was gone.

For long minutes after the door had banged after her husband, Marjorie Benton sat quietly in her chair, almost too stunned to think. Surely she must have been dreaming. Hugh had never before displayed such a temper. The things he had said were positively indecent. She was aroused from her reverie by the slamming of the front door and the sound of the machine going down the driveway. She sighed as she got slowly to her feet. She remembered she must talk to Elinor. She must not let what Hugh had said interfere with her duty. At the locked door she rapped softly.

“Who is it?” called the girl.

“It’s mother, dear! I have come to have a talk with you.”

“Sorry, mother, but I have a dreadful headache,” was the languid response. “You will have to wait until another time.”

“I am not going to scold—I just want to have a heart-to-heart chat with you, dear.” Marjorie was surprised at her own pleading voice as a lump rose in her throat.

“I’d rather not talk to-night, mother—please excuse me.”

“Very well,” Marjorie faltered, but as she turned toward her own rooms, the hot tears rolled down her cheeks.

On Tuesday afternoon, at precisely two o’clock, Templeton Druid parked his classy little roadster near the 57th Street entrance of the park, and paced slowly up and down. He was waiting for Elinor Benton. Time after time he glanced impatiently at his watch. He had never before waited for anyone—this was a new experience.

It was twenty minutes past two when he saw her alight from a taxi in front of the Plaza. He hastened forward to meet her. All his anger at her tardiness melted away immediately at sight of the beautiful girl in her stunning sport suit and hat of Chinese blue.

“I’m so sorry to have kept you waiting,” was her breathless greeting. “I—I—was unavoidably detained.”

She felt she just could not confess to this man her difficulties in endeavoring to get away from her mother.

Marjorie always attended a settlement meeting on Tuesday, so usually Elinor was free to do as she pleased; but to-day, the president had been reported ill and the meeting was postponed.

So it had been only through soliciting the aid of Mrs. DeLacy over the telephone that Elinor finally managed to keep her appointment. Mrs. DeLacy called for her in the Thurston car, begging that she accompany her to the dentist. Before her mother had a chance to utter a protest, Elinor had consented, so there was nothing for Marjorie to do. As soon as they were a safe distance from home, Elinor summoned a taxi and hastened to her rendezvous. But had she been able to read her dear Geraldine’s thoughts as that fair chaperone lounged comfortably on her way to the shopping district, the Benton heiress might not have felt so grateful as she went light-hearted to meet her matinée idol. For Geraldine DeLacy, widow, social parasite, chaperone de luxe, was racking her clever brains for a plan whereby she might most advantageously use the confidence Elinor had been obliged to place in her.

“Nothing matters, now that you are here,” was Templeton’s gallant reply to the girl’s apology. “I was only beginning to fear you would not come—but now——”

Elinor’s eyes were on the actor’s car as he led her to it. She glowed.

“What a stunning little car!” she cried, in delight.

To praise any of Templeton Druid’s possessions was the next best thing to praising him. But it was with a blasé air that he consented to agree with his guest, as he turned the wheel to head toward Long Island.

“Yes, she is a good little car,” he admitted, a bit boredly, as though condescending to praise the machine. “When we get out on the road, I’ll let her out a bit and show you what she can do.”

Elinor’s eyes gained a new sparkle as the air colored her cheeks.

“It seems wonderful to be riding like this,” she enthused. “I’m so tired of always riding behind a chauffeur. Dad wanted to buy me a car of my own, but mother wouldn’t consider it. He is going to buy one for my brother when he graduates, and then I’ll coax Howard into teaching me how to run it.” And Elinor’s eyes brightened with anticipation.

“You don’t have to wait for that,” Templeton answered magnanimously. “I’m going to teach you how to run mine this very day. Just as soon as we strike a nice stretch of road, I’ll put you at the wheel.”

“How perfectly splendid! But I’m afraid you will find me an awkward pupil.”

“I promise not to become impatient,” Templeton laughed, “but I warn you I may exact a tiny payment.”

Elinor caught her breath a little as she recognized the eager boldness with which the actor looked into her eyes, as they paused at a crossing at the command of the uplifted white hand of a traffic officer. But already she had determined that her companion should not put her in the class of the unsophisticated. For this one day she would put behind her all thoughts of prudishness, all the reminders of her mother’s teachings she had come so to despise, but had not quite forgotten. So her blush was belied by the boldness of her words as she pertly retorted:

“I’ve never yet heard a complaint that I don’t pay my debts!”

Templeton Druid smiled complacently as he turned in at the ferry entrance. This was going to be easier than he thought. But—oh, well, wasn’t that always the way. There was certainly something in being Templeton Druid.

It was a glorious day. The sun shone radiantly, and the balmy breath of spring with bewildering fragrance flooded the atmosphere.

Gradually her companion persuaded Elinor Benton to talk of herself and family. Before long she was telling him her life’s history without once suspecting that he had purposely encouraged her to do so.

“By the way,” he suddenly seemed to remember. “I forgot to tell you something. Through Mrs. DeLacy’s kindness I have received an invitation to a dance at the Thurstons’ on the 17th.”

“Splendid!” Elinor exclaimed, her eyes dancing her pleasure. “Of course, you’ll accept?”

The man shook his head slowly. “I have thought of declining because I can’t get there until after the theater,” he demurred, “and that will be so late, but of course, if you wish me to come——”

“Why, of course, I do—ever so much!”

“You’ll promise to save a dance for me?”

“Two,” promised the girl, her mind busily engaged with the thought of a wonderful new frock for the occasion.

True to his word, he put her at the wheel, and she thoroughly enjoyed her first lesson in driving. The rose color flamed in her cheeks, and her eyes sparkled like twin stars. Templeton Druid, glancing at her from the corner of his eye, caught his breath in admiration. “She is only a slip of a girl,” he thought. “But what a magnificent woman she will be!”

As they stood up to leave the little inn where they had their sandwiches and tea, the actor, in his most courtly manner bent over, and reaching for her hand, pressed his lips gently to the tips of her fingers.

His was a vast experience with women. It had taught him much, enough to realize that, impetuous and pampered as this girl was, he must use the utmost discrimination in endeavoring to arouse her admiration.

Elinor’s heart pounded bewilderingly as she withdrew her hand and turned toward the car. It had not resumed its rhythmic beating even when they reached the Plaza where they were met by Mrs. DeLacy, who was true to her promise to see Elinor through her escapade. Templeton Druid found time for one confidential whisper.

“Now don’t forget your promise,” he reminded, his tone languishing as though nothing else in the world meant so much. “Be sure to ’phone me to-morrow morning and let me know when I can see you again.”

Elinor nodded but her eyes betrayed much to that wise little lady when she took her seat by Geraldine DeLacy’s side in the Thurston limousine.