CHAPTER VII.

NONE BUT THE BRAVE.

“REALLY, Mab,” said Dick irritably, “your horses are more bother than they are worth. Why don’t you set up a motor-car?”

“How horrid you are, Dick! Any one would think it was my fault that all these things happen. How could I help one of the other horses’ kicking Majnûn as they were coming back from watering? I am sure it was that wretched Bayard of yours—cross old thing! At any rate, the syce declares it’s impossible for Majnûn to go out to-day, and I can see it myself. You can go round and look at the state his leg is in.”

“Oh, all right; I’ll take your word for it. But what are you going to do?”

“The syce’s sole idea is to send down to Mr Anstruther’s for Laili, but I don’t care to ride her again just yet.”

“No, I certainly won’t have you mount her until Anstruther can give a better report of her proceedings. Well, you had better take Georgie’s old Simorgh, as she and I are to do Darby and Joan in the dog-cart.”

“He’s so horribly and aggressively meek. I don’t want a horse whose sole title to distinction is that in prehistoric days he carried his mistress to Kubbet-ul-Haj and back without once running away. I am going to ride Roy, Dick.”

“My dear Mabel, pray have some regard for appearances. Will nothing but a mighty war-horse satisfy your aspiring mind?”

“That’s just it. He’s so big that it must feel like riding on an elephant. I should love to ride him, and you know it’s perfectly safe. A child could manage him—you said so yourself.”

“No, really, Mab. An appreciative country doesn’t provide me with chargers merely to furnish a mount for you.”

“Then I shall borrow a horse from somebody. Mr Burgrave would lend me anything he possesses in the way of horseflesh—he said so,” declared Mabel vindictively.

“I daresay, and rejoice when it came to grief, so that he might nobly refuse any compensation. Oh, take Roy, and Bayard too, if you like, and make the whole show into a circus, but don’t put me under an obligation to Burgrave.”

Mabel retired triumphant, as she had intended to do. It was the last day of the Christmas holidays, and the Alibad festivities were to close, as usual, with a picnic organised by Major and Mrs North. Georgia had been up long before dawn, superintending the packing of provisions in the carts, which must set out as soon as it was light, and she was now resting in her own room. Without troubling to ask herself why, Mabel felt relieved by her absence. She would not have cared to employ the argument with which she had vanquished Dick, had his wife been at hand, but she had no fear of his bearing malice or alluding to the matter afterwards. Perhaps he thought she was sufficiently punished already, for when she was perched upon the back of the great roan charger, she found that her victory was its own sole reward. Roy was almost as uncomfortable to ride as a camel, and to Mabel, accustomed to her docile ponies, he seemed to have no mouth at all. She was thankful to receive a hint or two on managing him from his forgiving master, and thus forearmed, she would not own herself defeated. Her mount excited a good deal of surprise among her fellow-guests, and Mr Hardy asked her benevolently if she would not have preferred an elephant, while Mr Burgrave reminded her in reproachful tones of his offer of the loan of any of his horses. To this she replied promptly that she preferred a military mount as more trustworthy, an answer which bred great, if somewhat causeless elation in the minds of several young officers who heard it.

The scene of the picnic was a spur of the mountains about a dozen miles to the north-east, where there were curious caves to be seen, and also the ruins of an ancient fortress, among which fragments, or even whole specimens, of old glazed tiles, very highly prized by those learned in such things, were sometimes found. On this occasion everything was done in the orthodox way. The caves were duly explored and the ruins examined, with suitable precautions against finding scorpions instead of tiles, and a few rather disappointing sherds were discovered, and entrusted to the servants to take home. Mabel and Flora Graham chose to climb to the highest point of the ruins, escorted and assisted by all the younger men of the party, but when there they confessed that, but for being able to say they had achieved the ascent, they had gained nothing that was not equally obtainable down below. However, the provisions were excellent, and nothing material to their consumption had been forgotten, so that the guests all agreed that it had been a most successful picnic, and Georgia heaved a sigh of satisfaction as she watched the servants piling the last of the empty baskets on the carts.

These carts, with the three or four carriages which had conveyed the elder members of the party, were obliged to return home by the track across the plain, but it was possible for the riders to take a short cut through the hills for the first part of the way. While a discussion was going on as to the path to be chosen, Flora Graham moved close to Mabel.

“Oh, Mab,” she murmured hastily, “do you think you could get Mr Brendon to ride with you? He persists in sticking to me, and I know Fred won’t like it when he hears. He’s a little inclined to be jealous, you know, because once, before we were engaged, he thought I liked Mr Brendon. Besides, I want to ride with Mr Milton, and talk to him about Fred.”

Milton, the youth who was Fred Haycraft’s comrade at Fort Shah Nawaz, had cheerfully put up with the fag-end of the holidays that his senior might enjoy as much of Miss Graham’s society as possible. He was delighted with the proposed arrangement, and Mabel had little difficulty in attaching Mr Brendon to herself when he found that the post he coveted was already bespoken. It was obvious, however, to keen-eyed observers that Mr Burgrave and Fitz Anstruther had both been promising themselves the pleasure of riding with Mabel, and the sudden blankness of their faces when they found themselves forestalled by this outsider was much appreciated. Finally, either moved by a certain vague fellow-feeling, or each impelled by the determination to see that the other played fair, they fell in together behind Mabel and her cavalier, riding rather in advance of the rest.

As for Mabel, she felt it distinctly hard to be obliged to sacrifice herself in this way for Flora’s benefit. Mr Brendon, of the Public Works Department, was a most estimable young man, but he suffered from a plethora of useful knowledge. To ask him a question was like pulling the string of a shower-bath, which let loose a flood of information on the head of the unwary questioner. Mabel had intended to let him prose as he liked, while she thought about other things, and jerked the string, so to speak, at the requisite intervals, but he was far too polite to monopolise the conversation. He paused for her replies or invited her opinion so often, while clearly ready to supply the needed answer himself, that she had not a moment for meditation, and found the ride almost unendurable. She had just succeeded in hiding an irrepressible yawn when a happy idea came to her as she was approaching a state of desperation.

“Oh, here is quite a nice level piece of ground! Let us race, Mr Brendon.”

He could not well refuse, and for all too short a time Roy pounded gallantly through the sand. Brendon’s lighter steed won easily, and when Mabel reached the end of the course, she found him waiting for her. At this point their road entered a narrow ravine, leading down to the open desert, and the high rocks on either side looked black and threatening against the glowing sunset sky, a glimpse of which at the farther end of the gorge dazzled the eyes.

“I think you had better let me pilot you here, Miss North,” said Brendon. “The ground is strewn with loose boulders, and it is difficult to distinguish them in this light. You might get a nasty fall.”

It was desirable that Brendon should ride anywhere rather than beside her, and Mabel accepted the position he assigned to her with something more than resignation. He took the lead as they entered the ravine, his pony picking its way with infinite caution, and Roy followed securely enough.

“What a delightful Dürer engraving we should make!” exclaimed Mabel suddenly, “creeping along between these dark cliffs under such a gorgeous red sky. But it’s contrary to all symbolism that you should be riding first.”

“The colour of the sky would scarcely tell in an engraving,” answered Brendon, with a perceptible accent of reproof. “But the idea would work out well in black and white.”

“Oh dear, no!” persisted Mabel. “The sky is everything. It gives such a threatening touch. I feel quite weird myself, don’t——”

“Don’t you?” she was going to say, but the words were cut short, for a shot was fired among the rocks on the left, close beside her. Roy, accustomed to such sounds, merely started slightly and pricked up his ears, but the pony shied violently, and received a cut from its rider.

“Abominable carelessness!” shouted Brendon to Mabel, looking round as the animal dashed forward. “I’m coming back to hunt that fellow out. He might have shot one of us.”

The words were scarcely out of his mouth before the pony reared suddenly and then fell forward, throwing him over its head. At the same moment Mabel heard the sound of another horse’s feet behind her, and before she could look round some one dealt Roy a smart blow on the flank. She felt him rise for a leap, and was conscious that his heels touched something as he went over. It seemed a miracle that he did not land upon his head, but as it was, the shock, when his hoofs clattered down amongst the stones, nearly unseated Mabel, and before she could collect her scattered senses three mounted men appeared, as if by magic, from among the rocks on either hand. Before she had time to do more than realise that they wore turbans, a fourth man pushed up from behind, and seizing her bridle, forced Roy into a canter. She had a momentary vision of Brendon, his face streaming with blood, flinging himself between her horse and her captor’s, and trying to wrest the bridle from him; she saw the sweep of steel in the red light as one of the other men turned round; saw Brendon cut down by a murderous blow from a tulwar. It was all over in a moment, and before she could even scream, she and her captors were out of the gorge and riding swiftly to the right, away from Alibad and safety. From the fatal spot they had left there came faintly to her ears the sound of several shots.

The sound reached other ears as well as Mabel’s. Mr Burgrave and Fitz, riding leisurely, as they had been when Mabel and her cavalier left them behind in their race, started when they heard it, and put spurs to their horses. Entering the gorge they could see nothing but dark rocks and lurid sky. No! what was that?—a bright flash, followed by another report, coming from a spot close to the ground at the farther end. Riding headlong down the ravine, regardless of the shifting boulders, they distinguished at last the form of Brendon, his light clothes dyed with blood. He was dragging himself painfully towards them, holding his discharged revolver in his left hand.

“They’ve got Miss North!” he gasped, as they neared him.

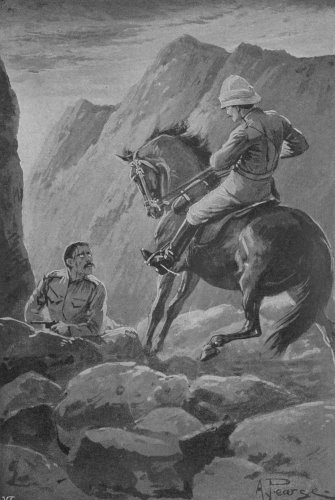

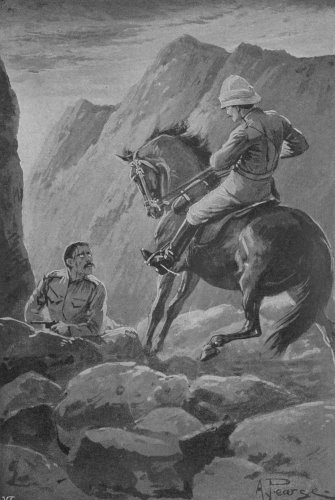

With a sharp exclamation Mr Burgrave dug his spurs deeper and dashed on, but Fitz, catching the look of agony on Brendon’s face, drew rein for a moment.

“FITZ CAUGHT THE LOOK OF AGONY IN BRENDON’S FACE”

“She’s riding—a troop-horse. Yell to him—to ‘Halt!’” came in broken sentences. “And look out. There’s a—rope.”

Even as he sank down exhausted from loss of blood, there was a crash in front. The Commissioner and his horse had gone down in a heap, marking only too accurately the position of the rope. Fitz galloped forward, his pony taking the obstacle like a bird.

“Ride on, for Heaven’s sake! Never mind me!” came in a despairing shout from the man who lay helpless under the struggling horse, and Fitz obeyed. He was out of the gorge now, and could see far away to the right the dark moving mass which represented the object of his pursuit. Ramming in his spurs, he followed at breakneck speed, his whole soul absorbed in the savage determination to catch up the robbers and their prey. Whether he and Sheikh lived or died, they must reach that goal. Thundering on, his eyes fixed upon his quarry, he perceived presently, with a fierce joy, that it was becoming clearer to his view. He was gaining! Now he could distinguish the forms of the men and their horses, and presently he was able to assure himself that the wiry little native steeds were undoubtedly handicapped by the necessity of accommodating their pace to that of the heavier Roy. That the robbers he was pursuing were four to one did not occur to Fitz, even in face of the ominous fact that they made no attempt to interfere with him, too confident in their superior numbers to take the trouble to separate and cut him off. The moment that he felt sure of his advantage, his plan was ready, formed complete in his mind, and without any volition of his own, his revolver was in his hand, cocked, the moment after. As he diminished the distance between himself and the robbers, he saw that they were no longer in a compact body. The three unencumbered riders were leading, and Mabel and the man who held her bridle came after. Mabel had recovered her presence of mind by this time. She was striking furiously with her whip at the hand which gripped her rein, in the hope of forcing the robber to loose his hold, but in vain. He could not spare a hand to snatch away the whip, but his grasp upon the bridle never relaxed. Suddenly a voice sounded in her ears. Standing in his stirrups, Fitz put all the power of his lungs into the one word, “Halt!” and at the well-known shout Roy stopped dead, his feet firmly planted together. The shock dragged the robber from his saddle, and his own horse, terrified, continued its headlong career. Still grasping Mabel’s bridle with his left hand, he drew his tulwar and sprang at Fitz. A bullet from the ready revolver met him as he came, and he fell forward, the tulwar dropping harmless from his fingers, which gripped for a moment convulsively at the sand under Sheikh’s hoofs.

“Quick! Get behind me! Crouch between the horses!” cried Fitz to Mabel, urging the panting Sheikh in front of Roy. The three men in front had faced round, and seemed to be meditating a charge, but they were without firearms, and Fitz, standing behind his pony, had them covered if they should approach. Left to themselves, they might have distracted his attention by coming at him from different directions, and taken him in the rear, but the other members of the party had now emerged from the gorge, and were riding down on them with shouts. Prudent counsels prevailed, and they turned their horses’ heads again, and rode off into the gathering darkness, leaving the victorious Fitz with two trembling, sweating horses, and Mabel, crouched on the sand, clutching wildly at his feet. She tried to speak as she looked up at him, but no words would come, and only a hoarse scream issued from her lips. The sight of her utter prostration almost unmanned him.

“Don’t, don’t, Miss North!” he entreated, trying to lift her up. “You’re safe now, and the others will be here in a minute. Don’t let them see you like this.”

She swayed to and fro as he raised her, and staggering to Roy’s side buried her face in his mane. Fitz turned away. It would be taking an unfair advantage, he felt, to speak to her in this forlorn state, and he began to pat Sheikh, and praise his gallant efforts in a low tone. Many a time afterwards did he curse himself as a fool for this backwardness of his, but at the moment it was impossible to him to take her in his arms and comfort her, as his heart urged him to do. She had been saved from death or worse by his means, and he could not presume upon the service he had rendered her.

The moment’s constraint was quickly ended by the eager questions of the men who came galloping up. Fitz stepped forward to meet them.

“Look out!” he said hastily, jerking his head in Mabel’s direction, “Miss North is awfully knocked up. Leave her to herself for a moment. Is Tighe here?”

“He stopped at the nullah. It’s a bad job there. Brendon’s gone, poor old chap! and the Commissioner’s pretty extensively damaged. Jolly good job the doctor was able to ride out this afternoon.”

“I say, look here,” said Fitz, “we mustn’t let her know about this. Can’t we get her straight home?”

“Must go back to the nullah. The Colonel and one or two more whose horses were no good stayed with Tighe to help him dig out the Commissioner. He had managed to shoot his horse, lest it should kick his brains out, but it was lying right across him. They’ll want help in getting him home, and poor Brendon too.”

“Well, say nothing to Miss North, and we’ll try to keep it dark. There, she’s coming. Can’t you say something ordinary?”

Milton, to whom the request—or rather command—was addressed, gasped helplessly. The circumstances seemed to preclude him from saying anything at all, but as Mabel came towards them, her face still white and her lips trembling, a happy thought seized two of the other men simultaneously.

“We’ve never even looked at the rascal you potted!” they cried to Fitz. “Here, come along. Who’s got a match?”

Mabel shuddered, and caught at Fitz’s arm, but a dreadful fascination seemed to draw her to the place where the dead robber lay. Some one produced a box of matches, and kneeling down, struck a light close to the face of the corpse. Fitz knew as well as Mabel what face she expected to see, and he could hardly keep himself from echoing her cry of surprise and relief when they realised that a stranger lay before them.

“Wait a minute, though,” said one of the officers, pressing forward. “Lend us another match, old man. Yes, I thought so! It’s Mumtaz Mohammed, the sowar who deserted five or six weeks ago. See, he has his carbine on his back.”

“Then it was only a common or garden raid, and not a planned thing,” said another. “I know it was said he had got away to those fellows who broke out of prison at Kharrakpur.”

“No,” said Mabel suddenly; “it was a plot.”

“Why, Miss North—how do you know?” they asked, astonished.

“Because my syce was in it. He told me this morning my pony could not be ridden, and wanted me to send for Laili, whom Mr Anstruther is training for me. She bolts at the sound of a shot. It was a shot fired in the nullah that began this—this——”

“And you didn’t ride Laili after all?”

“No, I would ride Roy. I asked for him just to see what Dick would say, and when he didn’t want me to have him, I persisted, simply to tease him. And it has saved my life!” she cried hysterically.

“Not much doubt who stood to benefit by the plot!” muttered one of the men who had stood behind Mabel at the Gymkhana, but Fitz nudged the speaker fiercely.

“I don’t know what we’re all standing here for—in case our deceased friend’s sorrowing relations like to come back and wipe us out, I suppose. Let me mount you, Miss North. Are you fellows going to stop out all night? Had we better bring that along, do you think?”

This was added in a lower tone, as he pointed to the robber’s corpse. After some demur it was decided to lay it across the saddle of Brendon’s pony, which had found its way back to the rest with a pair of broken knees, and they rode back towards the gorge, the last man leading the laden pony, so that it might be kept out of Mabel’s sight. As they approached the entrance to the ravine Dr Tighe came forward hastily to meet them.

“Look here,” he said, “I want some one to ride on to Alibad at once. The Commissioner has broken his knee-cap and a few other things, and Major North’s is the nearest house, but Mrs North mustn’t be frightened. Milton, your pony’s a good one, I know, so just take it out of him. Say nothing about Miss North or Brendon or anything, but tell Mrs North the Commissioner has had a nasty fall, and I am bringing him to her house with a fractured patella and a pair of smashed ribs. She can get things ready, and send on to my house for anything she doesn’t happen to have.”

“Surely the ladies had better go back with me, Doctor?” asked Milton, pausing as he was about to start.

“No, we don’t want any more kidnapping to-night. We must travel slowly, all of us, but they’ll be safer than with you. Feel shaky, Miss North? Drink this,” and he handed her a flask-cup. “Miss Graham is waiting to weep tears of joy over you. What, aren’t you gone yet, Milton?”

“Tell Major North to arrest the syce,” Fitz shouted after the messenger as he disappeared in the darkness.

“Off with your coats, you young fellows!” cried Dr Tighe, as the thud of the pony’s steps upon the sand died away. “The Commissioner has to be carried home somehow, and there’s not so much as a stick to make a stretcher of. We must tie the coats together by the sleeves, and manufacture a litter in that way.”

No one dared to scoff, although no one could understand what the doctor meant to do; but working energetically under his directions, they succeeded in framing a sufficiently practicable litter. Six of the party were chosen as bearers, and the others were to relieve them, their duty in the meantime being to lead the riderless horses and keep watch against a surprise. Mabel and Flora, who had been enjoying the luxury of shedding a few tears together in private, were placed at the head of the procession, and the march began. At first the litter containing the wounded man followed close after the two girls; but presently Fitz, who was one of the bearers, felt his arm grasped.

“Let the ladies get ahead of us, please. I—I can’t stand this very well.”

Fitz understood. Mr Burgrave was suffering acutely in being carried over the rough ground, and he feared lest some sound extorted from him by the pain should acquaint Mabel with the fact. The litter and its bearers dropped behind, and if now and then a groan was forced from the Commissioner’s lips, his rival, at any rate, felt no contempt for the involuntary weakness. Before half of the journey had been accomplished, a relief party, headed by Dick, met them, and Mr Burgrave was transferred to a charpoy carried by natives, after Dr Tighe had made rough and ready use of the splints and strapping Georgia had sent. A little later a detachment of the Khemistan Horse passed at a smart trot in the direction of the gorge. It was not now the rule, as in the early days of General Keeling’s reign, for the regiment to sleep in its boots, but it was still supposed to be ready day and night to trace the perpetrators of any outrage and bring them to justice—rough justice, sometimes, but none the less impressive for that. The sight gave Mabel a sense of safety and comfort, and she scouted Flora’s proposal that she should come home with her for the night.

“As if I would leave Georgie alone, with all this extra work on her hands!” she said, as they turned in at the gate.

“Oh, Mab, is it true about the Commissioner?” cried Georgia, coming out to meet them on the verandah.

“Yes; I am afraid he’s dreadfully hurt, poor man!”

“Was he riding with you when he fell?”

“He—he was riding after me,” said Mabel cautiously.

Georgia threw up her hands. “Oh, if you could only have hurt any other man, or taken him to any house but this!” she cried; and Mabel thought it both unkind and unfair, considering the circumstances.