CHAPTER XII.

HONOUR AND DUTY.

THREE or four days later, Mrs Hardy marched up the steps of the Norths’ bungalow with a purposeful mien, and requested an interview with the Commissioner. Mr Burgrave had finished his morning’s work early, and his couch had been placed in the drawing-room verandah. A table was close beside him, with a volume of Browning lying upon it, and there was a chair close at hand ready for Mabel, but she was out riding with Fitz, to whom Dick, in utter oblivion of the probable awkwardness of the situation, had hastily turned her over on finding that he himself was needed elsewhere. The Commissioner groaned impatiently when Mrs Hardy was announced. A talk with her was not the pleasure he had in view when he hurried through his work, but he consoled himself with the thought that she would not stay long. No doubt the Padri was anxious to get a new harmonium, or to enlarge the church, and they wanted him to head the subscription-list.

“Excuse my getting up,” he said, as he shook hands with her. “My sapient boy has put my crutch just out of reach.”

If the words were intended to convey a hint, Mrs Hardy did not choose to take it, for she sat down deliberately between the crutch and its owner. Then, without any attempt at leading up to the subject, she said, with great distinctness—

“I have come to talk to you about your policy, Mr Burgrave.”

The Commissioner stared at her in undisguised astonishment. “Pardon me; but that is a subject I do not discuss with—with outsiders,” he said.

“I only want to lay a few facts before you,” pursued Mrs Hardy unmoved.

“No, no; excuse me. I cannot consent to discuss affairs of state with a lady.”

“I mean you to listen to what I have to say, Mr Burgrave, and I shall stay here until you do.”

“I can’t run away,” said Mr Burgrave, with the best smile he could muster, and a side glance at the crutch; “and when a lady is kind enough to come and talk to me, it would be rude to stop my ears. Perhaps you will be so good as to let me know your views at once, then, that your valuable time may not be wasted?”

“I should like to ask you, first of all, whether you are aware that your confidential report to the Government on the frontier question is common property at Dera Gul? Of course, if you choose to tell your secrets to Bahram Khan and leave Major North in ignorance of them, I have nothing more to say.”

To her great joy, Mrs Hardy perceived that she had made an impression. The Commissioner looked startled and disturbed. “Impossible!” he said. “The report has been seen by no one but my secretary, and the clerks who copied portions of it.”

“It is for you to find out which is to blame. I can only tell you what is going on, just as it has been told to me. I was in my garden about an hour ago, when a woman peeped out from behind the bushes—a miserable, footsore creature. She told me she was a slave of the Hasrat Ali Begum’s—Bahram Khan’s mother—who had sent her to warn the Norths that you intend to withdraw the Nalapur subsidy, and leave Major North to face the result. I have no idea how Bahram Khan obtained the information, but he means to take advantage of it. Though she could not tell me what his plan is exactly, she seemed quite sure that it would end in a general rising, involving almost certain death to the Europeans in places like this. It was clear that she regarded you as a coward, running away from the consequences of your own acts, and deliberately exposing others to danger. That is not my opinion, I may say”—Mrs Hardy had seen the Commissioner wince—“but I thought you could not have looked at things in this light, and as soon as the poor creature was gone I came to you at once.”

“Confiding in Mrs North by the way, no doubt?”

“No, I came straight to you. Now let me ask you, have you realised what will be the result of your action? You know that Major North will resign rather than countenance what we all feel would be a gross breach of faith, and yet you place him in a position in which he must do one thing or the other. I don’t know what Miss North will think about it, but I know what I——”

“We will leave Miss North’s name out of the conversation, if you please.”

“Excuse me; we can’t. How do you expect her to feel towards you when you have set yourself deliberately to ruin her brother? You think worse of her than I do if you believe she will marry you after such a piece of cruel, unprovoked oppression.”

“Mrs Hardy, a lady is privileged——”

“Yes, I have no doubt you think I am taking an outrageous liberty, but I can’t and won’t be silent. All your interest in the frontier centres in a pretty, flighty girl who has no business to be here at all, and simply for the sake of showing your power you come and ride roughshod over us, whose lives are bound up in it. I know you’re a proud man, Mr Burgrave, and I don’t ask you to reverse your policy publicly, which you would naturally find a hard thing to do. But if this dreadful business has gone too far to be stopped, make Major North take a month’s leave, and carry it through yourself. Then the people will see that he is not responsible for the breach of faith, and he will come back and be your right hand when you most need him. What good could a stranger do when the tribes are out? Absolute ignorance of the country is not always the qualification it was in your case, you know. I know the frontier better than any other place in the world—we used to itinerate in the district for years before we were allowed to settle down—and I am certain there’s trouble coming. I can see it in the looks of the people, and hear it in the way they talk. And here on the spot are the Norths, the very people to deal with a crisis, and you have done your best to undermine their influence already. Can’t you stop there? What have they done that you should persecute them like this?”

“I assure you,” said Mr Burgrave slowly, “that I have the highest possible respect for both Major and Mrs North personally, but personality is not policy.”

“Up here it very often is. But come, Mr Burgrave, if you don’t absolutely hate the Norths, why not do as I suggest?”

“I promise you that every suggestion you have made shall receive the fullest consideration,” replied the Commissioner, in his best Secretarial manner. “I may rely upon your silence as to the matter?”

Mrs Hardy thought she detected a relenting in his tone. “Of course you may, if you are really going to do something. I am glad to find you open to conviction, if only for Miss North’s sake and your own. You will have a very pretty wife, and I trust a happy one. Ah, there she is!” as the sound of horses’ feet was heard, and Mabel, cantering past, waved her whip gaily to the watchers—“and riding with Mr Anstruther!”

“And is there any reason why she should not ride with Mr Anstruther?”

“His peace of mind, that’s all. But perhaps you think he deserves no mercy? I may tell you I was glad to hear of your engagement, since it saved that fine young fellow for a more suitable woman.”

“A more fortunate woman, doubtless,” corrected Mr Burgrave, with majestic forbearance. “A better there cannot be.”

Mabel was in the highest spirits as she mounted the steps after Fitz had ridden away. When he had appeared with the message that Dick was detained at the office, and had sent him to ride with her, her first impulse was to refuse to go, but other counsels prevailed. Fitz had offered no congratulations on her engagement, and the omission rankled in her mind. She was nourishing a reckless determination to provoke a scene by asking him what he meant by it, but her courage oozed away very soon after starting. She would still have given much to know what he thought of the whole situation, but she durst not venture upon an inquiry. Fitz, on his part, made no allusion to the important event which had occurred since their last ride, speaking of the Commissioner as coolly as if she had no particular interest in him. Before they had been out long, she was content to accept his ruling, and conscious of a kind of horror in looking back upon the resolution with which she had started. She was on good terms with herself once more, and to such an extent did the gloom cast by Mr Burgrave’s impressive personality seem to be lightened at this distance, that she returned home feeling positively friendly towards him. It was unfortunate that Mrs Hardy’s disapproving glance, when she encountered her on the steps, should clash with this new mood of cheerfulness, and that another shock should be awaiting her when she looked into the drawing-room verandah on her way to take off her habit.

“Little girl,” said her lover, holding out his hand to draw her nearer him, “would you mind very much if I said I had rather you didn’t take these solitary rides with young Anstruther?”

The angry crimson leaped up into Mabel’s forehead.

“You have no right whatever to make such insinuations!” she cried hotly.

“Now, dearest, you mistake me. I make no insinuations—I should not dream of such a thing. All I say is—doesn’t it seem more suitable to you, yourself, that until I am able to ride with you again you should not go out except with your brother? You will do me the justice to believe that I am not jealous—I would not insult you by such a feeling—but other people will talk. Yes, I am jealous—for my little girl, not of her. No one must have the chance even of passing a remark upon her.”

Mabel stood playing with her whip, her face flushed and her lips pressed closely together. “He would like to make life a prison for me, with himself as jailer!” she thought, as she bent the lash to meet the handle, making no attempt to listen to Mr Burgrave, who went on to speak of the high position his wife would occupy, of the extreme circumspection necessary in such a station, and of the unfortunate love of scandal characterising the higher circles of Indian female officialdom. He did not actually say that the future Mrs Burgrave must be above suspicion, but this was the general idea underlying his remarks.

“Why, you have broken your whip!” The words reached her ears at last. “Never mind, you shall have the best in Bombay as soon as it can come up here. You see what I mean, little girl, don’t you?”

“Oh yes,” said Mabel drearily. “You forbid me ever to ride with any one but you, or to speak to a man under seventy.”

“Mabel!” he cried, deeply hurt, “can you really misjudge me so cruelly?”

“It’s not that,” she said, kneeling down beside him with a sudden burst of frankness. “I know how fond you are of me, and I can’t tell you how grateful and ashamed it makes me. But you don’t understand things. You want to treat me like a baby, and I have been grown-up a long, long time. Think what I have gone through since I came here, even.”

“I know, I know!” he said hoarsely. “Don’t speak of it, my dearest! The thought of that evening in the nullah comes upon me sometimes at night, and turns me into an abject coward. I mean to take you away where you will be safe, and have no anxieties.”

“Then have you never any anxieties? Because they will be mine.”

“No,” he said, with something of sternness, “my anxieties shall never touch my wife. I want to shake off my worries when I leave the office, and come home to find you in a perfect house, with everything round you perfectly in keeping, the very embodiment of rest and peace, sitting there in a perfect gown, long and soft and flowing, for me to feast my eyes upon.”

He lingered lovingly over the contemplation of this ideal picture, to the details of which Mabel listened with a cold shudder. “My dear Eustace,” she said brusquely, to hide her dismay, “please tell me how you think the house and the servants are to be kept perfect, if I do nothing but trail round and strike attitudes in a tea-gown?” She caught his wounded look, and went on hastily, “And what did you mean by that invidious glance you cast at my habit? I won’t have my things sniffed at.”

“It’s so horribly plain,” pleaded the culprit.

“And why not?” demanded Mabel, touched in her tenderest point. “I’m sure it’s most workmanlike.”

“That’s just it. Workmanlike—detestable! Why should a woman want to wear workmanlike clothes? All her things ought to be like that gown you wore at the Gymkhana, looking as if a touch would spoil them.”

“I shall remind you of this in future, you absurd man!” laughed Mabel, regaining her cheerfulness as she thought she saw a way of establishing her point; “but please remember, once for all, that I shall choose my clothes myself—and they will be suitable for various occasions, for business as well as pleasure. Your part will only be to admire, and to pay.” There was a seriousness in her tone which belied the jesting words. Surely he would understand, he must understand, that there was a principle at stake.

“And that part will be punctually performed,” said Mr Burgrave indulgently, gazing in admiration into her animated face. “I know that you will remember my foolish prejudices, and gratify them to the utmost extent of my desires, if not of my purse. That is all I ask of you—to be always beautiful.”

In her bitter disappointment Mabel could have burst into tears.

“Oh, you won’t understand! you won’t understand!” she cried. “I don’t want piles of clothes; I don’t want everything softened and shaded down for me. I want to be a helpmate to my husband, as Georgia is to Dick.”

“Dear child, I am sorry you have returned to this subject,” said Mr Burgrave, taken aback. “I thought we had threshed it out fully long ago.”

“Ah, but we can speak more freely now!” she cried. “Don’t you see that I should hate to be stuck up on a pedestal for you to look at, or to be a kind of pet, that you might amuse yourself smilingly with my foolish little interests out of office hours? I want you to tell me things, and let us talk them over together, as Dick and Georgia do.”

“I know they do,” said Mr Burgrave, trying to smile. “The walls here are so thin that I hear them at it every evening. A prolonged growl is your brother soliloquising, and a brief interlude of higher tones is Mrs North giving her opinion of affairs. It is a little embarrassing for me, knowing as I do that my doings are almost certainly the subject of the conversation.”

“Well, and if they are?” cried Mabel. “It is only because you and Dick don’t understand one another that he and Georgia criticise you. Now think about this very matter of the frontier. If you would only talk to me, and tell me what you thought was the proper thing to be done, I could talk to them, and you might find out that your views were not so much opposed after all. Do try, please; oh, do! I would give anything to bring you to an agreement.”

Mr Burgrave’s brow was clouded as he looked into her eager eyes.

“Am I to understand,” he said, with dreadful distinctness, “that your brother and Mrs North are trying to make use of you to extract information from me? No, I will not suspect your brother. No man would stoop to employ such an expedient—so degrading to my future wife, so affronting to myself. It is Mrs North’s doing.”

Mabel, who had listened in horrified silence, sprang to her feet at this point as if stung. “I think it will be as well for me to return you this,” she said, laying upon the table the ring of “finest Europe make,” which the Commissioner had been fain to purchase from the chief jeweller in the bazaar as a makeshift until the diamond hoop for which he had sent to Bombay could arrive. “You have grossly insulted both Georgia and me, and—and I never wish to speak to you again.”

She meant to sweep impressively from the room, but the angry tears that filled her eyes made her blunder against the table, and Mr Burgrave, raising himself with a wild effort, caught her hand. “Mabel, come here,” he said, and furious with herself for yielding, she obeyed. “Give me that ring, please.” He restored it solemnly to its place on her finger. “Now we are on speaking terms again. Dear little girl, forgive me. I was wrong, unpardonably wrong, but I never thought your generous little heart would lead you so far in opposing my expressed wish. I admire the impulse, my darling, but when you come to know me better you will understand how unlikely it is that I should yield to it. Come, dear, look sunny again, or must I make a heroic attempt to go down on my knees with one leg in splints?”

“Oh, if you would only understand!” sighed Mabel. She was kneeling beside him again, occupying quite undeservedly, as she felt, the position of suppliant. “If only I could make you see——”

“See what?” he asked, taking her face in his hands and kissing it. “I see that my little girl thinks me an old brute. Won’t she believe me if I assure her on my honour that I am trying to do the best I can for her brother, and that I hope I have found a way of putting things right?”

“Have you, really?” Her bright smile was a sufficient reward. “Oh, Eustace, if it’s all settled happily, I shall love you for ever!”

The assurance did not seem to promise much that was new when the relative position of those concerned was considered, but the unsolicited kiss bestowed upon him was very grateful to Mr Burgrave, and he smiled kindly as he released Mabel and bade her run away and change her habit. She left the room gaily enough, but once outside, a sudden wave of recollection swept over her, and she wrung her hands wildly.

“I was free—free!” she cried to herself. “Just for a moment I was free, and I let him fetch me back. Oh, what can I do? I believe I could be quite fond of him if he would let me, but he won’t. And if he wasn’t so good I should delight to break it off in the most insulting way possible, but his virtues are the worst thing about him. I hate them! Is this sort of thing to go on for a whole lifetime—beating against a stone wall and bruising my hands, and then being kissed and given a sweet, and told not to cry? Mabel Louisa North, you are a silly fool, and you deserve just what you have got. I hate and despise you, and with my latest breath I shall say, Serve you right!”

“Oh, Dick, has it come?” Georgia sprang up to meet her husband, as he entered the room with a gloomy face.

“No, but so far as I can see, it’s close at hand. I can’t quite make things out, but Burgrave seems to have altered his plans astonishingly. Instead of travelling down to the coast at once, he is going to stay here another week, and hold a durbar at Nalapur. I have to send word to Beltring at once to get the big shamiana put up in the Agency grounds, and to see that all the Sardars have notice. What does it mean?”

“He’s going to see the thing through on his own account,” said Georgia, with conviction. “But it will make no difference to us, will it, Dick?”

“Rather not! The breach of faith is the same, whether I announce it at first, or merely come in afterwards to carry it out. I wish Burgrave hadn’t such a mania for mysteries. Ismail Bakhsh tells me he has been sending off official telegrams at a tremendous rate all day, and yet when I ventured to hint that some idea of the proposed proceedings at the durbar would be interesting, he turned rusty at once, and said he had not received his instructions. This system of government by thunderbolt doesn’t suit me. It’s enough to make a man chuck things up now, without waiting for the final blow.”

“Oh, but you will stick on as long as you can? It’s some sort of security for peace.”

“A wretchedly shaky one, then,” said Dick, with an angry laugh. “Here’s the Amir sending his mullah Aziz-ud-Din to say that he learns on incontestable authority that the subsidy is to be withdrawn, and imploring me to say whether I have any hand in it. The poor old fellow’s faith in me is quite touching, but what could I say except that I knew nothing about it, and repeat the assurance I gave him before?”

“But what could Ashraf Ali mean by incontestable authority?”

“How can I tell? Some spy, I suppose. By the way, though, it didn’t strike me. That must be what the Commissioner meant!”

“Why, what did he say?”

“He doesn’t intend to stay on in this house. Now that he can be got into a cart, he thinks it better to return to his hired bungalow. I imagine I looked a bit waxy, for he graciously explained that he had reason to believe we have spies among the servants here.”

“Dick! you don’t mean to say that he accused you——?”

“No, he was so good as to assure me that he had the best possible means of knowing I had nothing to do with it. But when I reminded him that all the servants, except those Mab brought with her from Bombay, have been with us for years, he intimated that he made no accusations, but official matters had got out, and he didn’t mean to allow that sort of thing to go on. No doubt it was that sweetseller fellow, as we thought.”

“Well, I think that to go is the best thing the Commissioner can do. It will give Mab a little peace.”

“Yes, I shouldn’t say she looked exactly festive.”

“How could she? She feels that she has cut herself off from us, for of course we can’t discuss things before her as we used to do, and I don’t think she finds that he makes up for it. I have great hopes.”

“Now, no coming between them!” said Dick warningly, and Georgia laughed.

“I trust it won’t be necessary,” she said.

A week later she happened to be again sitting alone in the drawing-room, busy with the fine white work on which she expended so many hours and such loving care at this time, when Dick came in. To her astonishment, he was in uniform, and laid his sword upon the table by the door as he entered.

“Why, Dick, you are not going to Nalapur with the Commissioner after all?” she cried.

“Burgrave can’t go, and I have to hold the durbar instead.”

“But how—what——?”

“It seems that he had a fearful blow-up with Tighe this morning, after taking it for granted all along that he would be allowed to leave off his splints and go. Tighe absolutely howled at the idea, told him that in moving from this house to his own he had jarred the knee so badly as to throw himself back for a week, and that the splints must stay on for some time yet. Of course he can’t ride in them, and to take him through the mountains in a doolie would be madness.”

“I wondered at his being allowed to ride so soon,” said Georgia, “but I thought Dr Tighe must have found him better than we expected. Of course I haven’t seen the knee for some time lately. But did he tell you what the object of the durbar was?”

“He did. It is just what we thought it would be, Georgie.”

“Nonsense!” cried Georgia sharply. “As if you would go to Nalapur in that case! Are you joking, Dick?”

His set face brought conviction slowly to her mind.

“You are not joking, and yet you came home, and got ready, just as if you meant to hold the durbar, and never told me!” she cried.

“I do mean to hold the durbar,” said Dick.

She sat stunned, and he went on: “I thought I wouldn’t tell you till the last moment, because I knew how you would feel about it, and I didn’t want to worry you more than could be helped.”

“To worry me!” she repeated. “And yet you come here and try to tease me with this absurd, impossible story? You are not going.”

Dick looked her straight in the face. “But I am,” he said.

“But you said you would resign first.”

“I must resign afterwards, that’s all. There are some things a man can’t do, Georgie, and one is to desert in the face of the enemy.”

“But it’s wrong—dishonourable!”

“It’s got to be done, and Burgrave has managed to engineer matters so that I have to do it. I talked about resigning, and he said very huffily that he wasn’t the person to receive my resignation, which is quite true. He anticipates danger, I can see, for he tells me he has had information that Bahram Khan has some sort of plot on hand, and do you expect me to hang back after that?”

“I never thought you would care what people said. If it’s right to resign, do it, and let them say what they like.”

“If I wasn’t a soldier I would, but I have no choice.”

“No choice between right and wrong?”

“Not as a soldier. It isn’t my business to criticise my orders, but to execute them. Oh, I know all you are thinking. I see it perfectly well, and from your point of view you are absolutely in the right, and as an individual I agree with you, but I am not my own master.”

“And your personal honour?”

“I’m afraid it has got to look after itself. Don’t think me a brute, Georgie. I want to be on your side, but I can’t.”

“Then I suppose it’s no use my saying anything more?”

“I really think it would be better not. You see, it would only make us both awfully uncomfortable, and do no good.”

“Oh, don’t!” burst from Georgia. “I can’t bear to hear you talk like that. Remember your promise to Ashraf Ali. The poor old man has relied on that, and pledged himself to all the Sardars that the Government doesn’t intend to forsake them. The whole honour of England is at stake. Dick, these people have learnt from you and my father to believe the word of an Englishman, and are you going to teach them to distrust it now?”

“When you have quite finished——” began Dick.

“I can’t! I can’t! Oh, Dick, our own people, who know us and trust us! Have you the heart to forsake them? Dick, won’t you listen to me? I have never urged you to do anything against your will before, but when it is a matter of right and conscience—! I know you believe you’re right now, but how will you feel about it afterwards? Think of our friends betrayed, our name disgraced, through you!”

“Hang it, Georgie!” cried Dick, losing his temper, “you make a man feel such a cur. I tell you I have got to go.”

“I wish I had died when baby died at Iskandarbagh, rather than lived to hear you say that.”

Dick turned away without answering, and took up his sword from the table where he had laid it down. It was always Georgia’s privilege to buckle the sword-belt for him, and she rose mechanically, rousing herself with an effort from her stupor of dismay. He took the strap roughly out of her hands.

“No,” he said, “you’d better have nothing to do with it. The blame is all mine at present, and you can keep your own conscience clear.”

She sank upon a chair again and watched him miserably as he buckled on the sword and went out. On the threshold he looked back, softening a little.

“Graham has changed his mind, and is not coming to the durbar. If there should be any attempt at a rising, you are to take refuge in the old fort. Tighe will come and sleep in the house these two nights if you are nervous.”

“I’m not nervous,” said Georgia indignantly.

“Oh, very well. After all, we shall be between you and Nalapur.”

He crossed the hall to the front door, Georgia’s strained nerves quivering afresh as his spurs clinked at each step. Suddenly she realised that he was gone, and without bidding her farewell.

“Dick!” she cried faintly, “you are not going—like this?”

There was no answer, and she moved slowly to the window, supporting herself by the furniture. He was already mounted, and was giving his final directions to Ismail Bakhsh. The sight gave Georgia fresh strength, and stepping out on the verandah, she ran round the corner of the house. There was one place where he always turned and looked back as he rode out. He could not pass it unheeded even now, that spot, close to the gate of the compound, where she had so often waited for his return. As she stood grasping the verandah rail with both hands, the consciousness that for the first time in their married life he was leaving her in anger swept over her like a flood.

“Oh, it will kill me!” she moaned, seizing one of the pillars to support herself, but almost immediately another thought flashed into her mind. “No, he is not angry—my dear old Dick! he is only grieved. He durst not be kind to me, lest I should persuade him any more, and he should have to give way. God keep you, my darling!”

In the rush of happy tears that filled her eyes, the landscape was blotted out, and when she could see distinctly again, Dick had passed the gate. She could just distinguish the top of his helmet above the wall as he rode. He had gone by while she was not looking. Would it have been any comfort to her to know that he had looked back, and not seeing her, had ridden on faster?

“I had to behave like a brute, or I should have given in—and she didn’t see it,” he said to himself remorsefully. “Of course she was right, bless her! She always is, but I couldn’t do anything else.”

Her pale reproachful face haunted him, and had there been time he would have turned back, but he was obliged to hurry on. As he entered the town, he came upon Dr Tighe.

“Doctor,” he said, laying a hand on the little man’s shoulder, “look after my wife while I’m away. She’s awfully cut up at my going like this.”

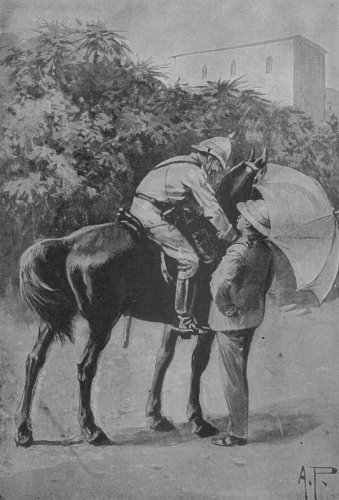

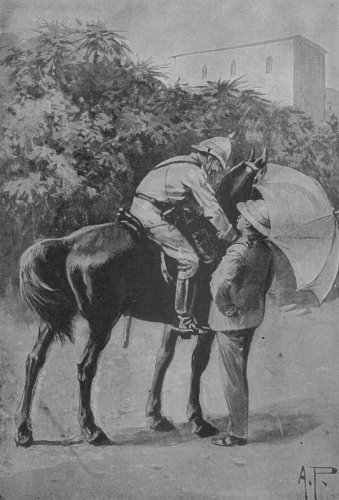

“LOOK AFTER MY WIFE WHILE I’M AWAY”

“All right!” said the doctor cheerfully; “and don’t you be frightened about her. Mrs North is a sensible woman, and knows better than to go and make herself ill with fretting.”

“The Memsahib parted from the sahib without kissing him!” said one of the servants wonderingly to the rest.

“What foolish talk is this?” asked Mabel’s bearer scornfully. “My last Memsahib never kissed the Sahib unless he had gained her favour by a gift of jewels.”

The tone implied that the subject might be dismissed as beneath contempt, but the man’s actions did not altogether tally with