CHAPTER XVI.

THE DARKEST HOUR.

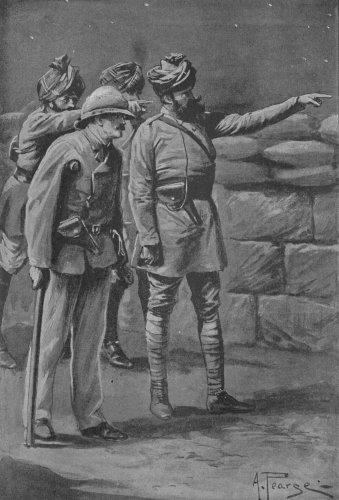

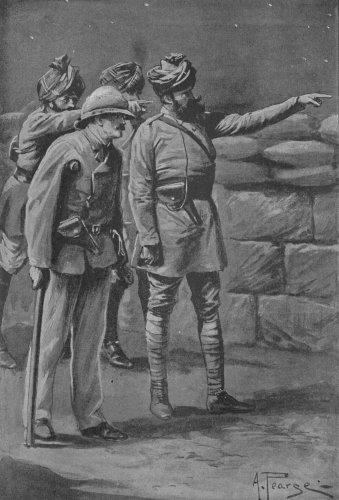

“SAHIB, there is a man under the wall on the east side.”

“How did he come there?” demanded Colonel Graham angrily. “What are the sentries doing?”

“The night is so dark, sahib, that he crept up unnoticed. He is the holy mullah Aziz-ud-Din, and desires speech with your honour.”

“The Amir’s mullah? You are sure of it?”

“I know his voice, sahib. He is holding his hands on high, to show that he has no weapons.”

“I suppose we may as well see what he has to say,” said the Colonel to Mr Burgrave, with whom he had been making final arrangements, and the two men climbed the steps to the east rampart. Once there, and looking over into the darkness, it was some little time before their eyes could distinguish the dim figure at the foot of the wall.

“Peace!” said Colonel Graham.

“It is peace, sahib. I bear the words of the Amir Ashraf Ali Khan. He says, ‘It is now out of my power to save the lives of the sahibs, and I will not deceive them, knowing that a warrior’s death amid the ruins of their fortress will please them better than to fall into the hands of my thrice-accursed nephew, who has stolen the hearts of my soldiers from me. But this I can do. The houses next to the canal on this side of the fort are held by my own bodyguard, faithful men who have eaten of my salt for many years, and I have there six swift camels hidden. Let the Memsahibs be entrusted to me, especially those of the household of my beloved friend Nāth Sahib, and I will send them at once to Nalapur, where they shall be in sanctuary in my own palace, and I will swear—I who kept my covenant with the Sarkar until the Sarkar broke it—that death shall befall me before any harm touches them.’”

“Why is this message sent to-night?” asked Colonel Graham.

“Because Bahram Khan is preparing a great destruction, sahib, and the heart of Ashraf Ali Khan bleeds to think that the houses of his friends Sinjāj Kīlin Sahib and Nāth Sahib should both be blotted out in one day.”

“Carry my thanks and those of the Commissioner Sahib to Ashraf Ali Khan, but tell him that the Memsahibs will remain with us. Their presence would only place him in greater danger, and he would not be able to protect them. But we can. They will not fall into the hands of Bahram Khan.”

“It is well, sahib.” The faint blur which represented the messenger melted into the surrounding blackness, and Colonel Graham turned to his companion.

“It will be your business to see to that, if the enemy break in. Haycraft comes with me. We must leave Flora in your charge. Don’t let her fall into their hands, any more than Miss North.”

“I promise,” said Mr Burgrave, and their hands met in the darkness.

“Thanks. I think we have settled everything now. We don’t start for an hour yet, and if you like to explain things to Miss North——”

“I should prefer to say nothing unless the necessity arises.”

“I never thought of your going into details, but she must know something, surely? Flora will learn the state of affairs from Haycraft; Mrs North will pick it up from the Hardys and her ayah, and Miss North will probably expect—— But please yourself, of course.”

“I will go and talk to her for a little while. I have scarcely seen her all day.”

Mr Burgrave’s tone was constrained. It seemed to him almost impossible to meet Mabel at this crisis, and abstain from any allusion to the terrible duty which had just been laid upon him. He was not an imaginative man, and no forecast of the scene burned itself into his brain, as would have been the case with some people, but the oppression of anticipation was heavy upon him. For him the dull horror in his mind overshadowed everything, and it was with a shock that he found Mabel to be in one of her most vivacious and aggressive moods. She was walking up and down the verandah outside her room as if for a wager, turning at each end of the course with a swish of draperies which sounded like an angry breeze, and she hailed his arrival with something like enthusiasm, simply because he was some one to talk to.

“Flora is crying on Fred’s—I mean Mr Haycraft’s—shoulder somewhere,” she said; “and Mrs Hardy and Georgia are having a prayer-meeting with the native Christians. They wanted me to come too; but I don’t feel as if I could be quiet, and I shouldn’t understand, either. What is going to happen, really?”

“The Colonel proposes to make a sortie and capture the two guns which the enemy have brought up. There is, I trust, every prospect of his succeeding.”

Mabel stamped her foot. “Why can’t you tell me the truth, instead of trying to sugar things over?” she demanded. “It would be much more interesting.”

“You must allow me to decide what is suitable for you to hear,” said Mr Burgrave, his mind still so full of that final duty of his that he spoke with a serene indifference which Mabel found most galling.

“I don’t allow you to do anything of the sort. I wish you wouldn’t treat me as if I was a baby. It’s like telling me yesterday that all the fresh milk in the place was to be reserved for us women and the wounded, as if I wanted to be pilloried as a lazy, selfish creature, doing nothing and demanding luxuries!”

“My dear little girl, I am sure there isn’t a man in the garrison who would consent to your missing any comfort that the place can furnish.”

“That’s just it. I want to feel the pinch—to share the hardships. But of course you don’t understand—you never do.” She stopped and looked at him. “I don’t know how it is, Eustace, but you seem somehow to stir up everything that is bad in my nature. I could die happy if I had once shocked you thoroughly.”

He recoiled from her involuntarily. “Do you think it is a time to joke about death when it may be close upon you?” he asked, with some severity.

“That sounds as if you were a little shocked,” said Mabel meditatively. “But you know, Eustace, whenever you tell me to do anything—I mean when you express a wish that I should do anything—I feel immediately the strongest possible impulse to do exactly the opposite.”

“But the impulse has never yet been translated into action?” he asked, with the indulgent smile which was reserved for Mabel when she talked extravagantly.

“I’m ashamed to say it hasn’t.”

“Then I am quite satisfied. I can scarcely aspire to regulate your thoughts just at present, can I? But so long as you respect my wishes——”

“Oh, what a lot of trouble it would save if we were all comfortably killed to-night!” cried Mabel, with a sudden change of mood. Mr Burgrave was shocked, and showed it. “I’m in earnest, Eustace.”

“My dear child, you can hardly expect me to believe that you would welcome the horrors which the storming of this place would entail?”

“Oh no; of course not. You are so horribly literal. Can’t you see that my nerves are all on edge? I do wish you understood things. If you won’t talk about what’s going to be done to-night, do go away, and don’t stay here and be mysterious.”

“Dear child, do you think I shall judge you hardly for this feminine weakness? You need not be afraid of hurting or shocking me. Say anything you like; I shall put it down to the true cause. If your varying moods have taught me nothing else, at least I have learnt since our engagement to take your words at their proper valuation.”

“If you pile many more loads of obligation upon me, I shall expire!” said Mabel sharply, only to receive a kind smile in return. Anything more that she might have said, in the amiable design of shocking him beyond forgiveness, was prevented by the appearance of Mrs Hardy.

“Is it true that you are going to arm all the civilians in the place, Mr Burgrave?” she demanded of the Commissioner.

“It is thought well—merely as a precautionary measure.”

“Then I do beg and beseech you to give Mr Hardy a rifle that won’t go off, or we shall all be shot.”

“We will get the Padri to go round and hand out fresh cartridges, instead of giving him a gun,” said Mr Burgrave seriously, but Mabel burst into a peal of hysterical laughter, which was effectual in putting a stop to further conversation, and he returned to the outer courtyard, where the men chosen for the forlorn hope were mustering in readiness for the start. Fitz and Winlock and their small party had left already, officers and men alike wearing the native grass sandals instead of boots, as they had been accustomed to do in their hunting expeditions, and it was known that they had scrambled along the wall and round the base of the south-western tower in safety. The ferry had by this time been successfully constructed by Runcorn and his assistants, one of whom had undertaken the very unpleasant task of swimming across the ice-cold canal to pass the first wire rope round one of the posts which registered the height of the water on the opposite bank. Ball ammunition in extra quantities was served out to the whole force, for although Colonel Graham hoped to confine himself entirely to cold steel, for the sake of quietness, he was determined to be able to reply to the enemy’s fire, should their attention unfortunately be aroused. The men were marched down in parties to the water-gate, and ferried over as quickly as the confined space would allow, and when all had crossed, the raft was drawn back to the gateway, and the wire disconnected. It had been decided that this was imperative, lest the enemy should take advantage of the ferry to cross the canal while the attention of the garrison was occupied by an attack in front. If the forlorn hope returned victorious, it would be easy to reconstruct the ferry by throwing a rope to them from the rampart, while if they were compelled to retreat, the raft was so small that to employ it under fire would entail a useless sacrifice of life, and the fugitives would do better to swim.

Then began a weary waiting-time for those in the fort. The night was moonless, so that it was impossible to distinguish any movement, whether on the part of friend or of foe. At last a rocket, rising from the cliff which overhung the town on the north-west, and which Fitz and Winlock had indicated as their goal, showed that they, at least, had so far been successful. The rocket sent up from the fort in reply was answered by another from the cliff, and this was immediately followed by the distant sound of brisk firing, which seemed to cause considerable perturbation in the parts of the town occupied by the enemy. Lights moved about hurriedly from place to place, horns were blown, and there was a confused noise of angry shouting. The garrison did their best, by opening fire from the wall and towers, to increase the effect of the surprise, but without much hope of hitting anything, for the moving lights did not afford very satisfactory targets. In reply, a dropping fire broke out from the houses opposite, which was maintained for some time, but with little spirit, and slackened gradually. Scarcely had Mr Burgrave given the order to cease fire, however, when a heavy fusillade was heard on the west of the fort, though not from the hill. The sound appeared to come from the point at which the bridge, now in ruins, had crossed the canal, a point which it had not hitherto been known that the enemy were occupying, and which Colonel Graham had not intended to approach. His force should have been far to the left of it by this time, and already mounting the hill. The most probable explanation seemed to be that they had missed their way in the darkness, and following the bank of the canal too far, had fallen into an ambuscade posted at the ruins of the bridge to guard against any attempt to cross for the purpose of capturing the guns. The Commissioner and his garrison waited and listened in the deepest anxiety, straining their eyes to try and perceive, from the flashes of the rifles, which way the fight was tending. But the firing ceased suddenly, as that on the farther side of the enemy’s position had done some time before. There was nothing to do but wait.

Suddenly, after a long interval, a piteous wailing arose at the rear of the fort, from the opposite bank of the canal. A native stood there, one of the water-carriers who had accompanied the force, abjectly entreating to be fetched over, since the enemy were at his heels. To employ the ferry at such a moment was not to be thought of, but a rope was thrown from the steps of the water-gate, and the miserable wretch, plunging in, caught it, and was drawn across. He told a terrible tale as he stood dripping and shivering in the passage leading to the gate. Colonel Graham’s force had been attacked, shortly after leaving the canal-bank, by overwhelming numbers of the enemy, who had first poured in a withering fire, and then rushed forward to complete the destruction with their knives and tulwars. The bhisti himself was the only man who had escaped, and the enemy had pursued him to the very edge of the canal. The sharpest-sighted men in the fort, sent to the rampart to test the truth of this statement as far as they could by starlight, were obliged to confirm it. There was undoubtedly a large body of the enemy on the other side of the canal. They were lying down behind the high bank, so as to be sheltered from the fire of the garrison.

“To cut off fugitives, I suppose,” muttered Mr Burgrave, half to himself and half to Ressaldar Ghulam Rasul. “That looks as though the massacre were not quite so complete as—Hark! I thought I heard a sound from the hill. Can our glorious fellows have made a last dash for it after all—some few who escaped?”

The men on the rampart stood like statues to listen, but failed to distinguish anything that might confirm the Commissioner’s surmise. The air seemed full of sound—footfalls, a murmur from the town, a stray shot or two from the same direction, and on the west a kind of shuffling noise. The enemy were taking up their positions for the attack. Mr Burgrave sent orders to the guard at the water-gate to let the air out of the inflated skins which supported the raft, so as to sink it to the level of the water, and this was at once done. When he had posted a sentry in the passage and another on the rampart above it, he was able to leave that side of the fort to defend itself, since the enemy had no means of crossing to assail it. To occupy the whole range of wall with the absurdly small force at his disposal was obviously impossible, and he therefore placed ten men in each of the larger towers, from which, with the usual amount of trouble and risk, a flanking fire could be obtained, and twelve in the two gateway turrets, retaining the Ressaldar and sixteen men as a reserve, ready to make a dash for any point that might be specially threatened. If the garrison should be driven from the walls, those who escaped were to rush for the hospital, where the women and children would take refuge, and the last stand was to be made. Having ordered his forces to their stations, the Commissioner went the round of the towers to encourage the men. His own Sikhs he could deal with well enough, but he felt that it was the irony of fate which obliged him to urge the sowars of the Khemistan Horse to show themselves worthy of their first commander, General Keeling, and it seemed as if the same thought had occurred to the men, for they scowled at him resentfully when they heard the mighty name from his lips.

The bad news brought by the fugitive spread through the fort with astonishing rapidity. The native women, whom Georgia had succeeded in soothing into some sort of calmness before the departure of the forlorn hope, filled the air with their wailings, until Ismail Bakhsh, who was head of the civilian guard detailed for the defence of the hospital, threatened to fire a volley among them if they were not quiet. Flora Graham’s ayah was gossiping with a friend among these women when the news arrived, and she rushed with it at once to her mistress’s room. Poor Flora had shut herself up alone to pray for the safety of her father and lover, and was following in thought every step of their perilous march. She had just reached with them the summit of the hill, and rushed upon the guard round the guns, when the ayah burst in with the news that the worst had happened. The sudden revulsion of feeling was too much for Flora. Her usual self-control deserted her, and she ran wildly across the courtyard to Georgia’s room. Georgia was lying down, talking softly in the dark to Mabel, who sat beside her, and both sprang up at Flora’s entrance.

“What is it? Have they come back?” they demanded, with one voice.

“No, no; they are killed—all killed! Papa and Fred both—oh, Mrs North, what can I do?” She dropped sobbing on the floor at Georgia’s feet, and buried her face in her dress.

“Perhaps it isn’t true,” suggested Georgia faintly. She had sunk down again on the bed.

“There’s no hope—one man has come back, the only survivor. Both of them at once! and I was praying for them, and I felt so sure—and even while I was praying they were being killed.”

“Is the whole force cut off?” asked Georgia, almost in a whisper.

“All but this one man.” Flora checked her sobs for a moment to answer.

“Fitz Anstruther too?” cried Mabel sharply.

“All, I tell you! It doesn’t signify to you, Mab; you have your Eustace left, but I have lost everything. Oh, Mrs North, you know how it feels. Help me to bear it.”

“Flora dear,” began Georgia, with difficulty. “I—I can’t breathe,” she gasped, struggling to stand up. “Please ask Mrs Hardy to come. I feel so faint. She will understand.”

Rahah, who had been crouched in the corner as usual, sprang up and ran out, returning in a moment with Mrs Hardy, who fell upon both girls immediately, and drove them out with bitter reproaches.

“You pair of selfish, thoughtless chatterboxes! I should have thought you had more sense, Flora. Just be off, both of you. You can have my rooms for the rest of the night; I shall stay here. Even if all our poor fellows are killed, is that any reason for killing Mrs North too?”

“Oh, please don’t, Mrs Hardy! I never thought—Mrs North is always so kind, and I am so miserable,” sobbed Flora.

“You shouldn’t be miserable unless you’re quite certain it’s necessary. You wouldn’t believe a native who told you he was dead, as they are always doing; so why should you when he says other people are dead?” demanded Mrs Hardy, with a brilliancy of logic which somehow failed to satisfy. “I haven’t a doubt that the bhisti took to his heels in a panic at the sound of the first shot, and if he hadn’t fortunately been in the rear, the panic might have spread to all the rest. There, go away, do, and don’t cry so. We’ll hope all will go well.”

“Why have you left your post, doctor?” asked Mr Burgrave, meeting Dr Tighe crossing the courtyard.

“The hospital will have to look after itself a good deal to-night, but I have left the Padri and my Babu in charge there. Mrs North is taken ill.”

“Good heavens! It only needed this to make the horror of the situation complete.”

“From our point of view, it may be the best thing that could happen. It will make the men fight like demons. Here, you girl, where are you going?” He had caught the shoulder of a veiled woman who ran up and tried to slip past him into the passage, but she let her chadar fall aside, and disclosed herself as Rahah.

“I have been telling the men of the regiment, sahib, and they have all sworn great oaths that so long as one of them has a spark of life left Sinjāj Kīlin’s daughter shall not be without a protector in her need, and that the corpses of foes without and friends within shall be piled as high as the ramparts before the enemy shall gain a footing on the wall. I told also those in the hospital”—there was a hint of malice in Rahah’s voice—“and every wounded man who can sit up in bed is crying out for a gun. They will serve as hospital guard, they say, and set Ismail Bakhsh and his men free to fight on the walls.”

“Good idea, that!” said Dr Tighe, turning to the Commissioner. “You see how the men take it. Well, I shall keep Mrs North in her own quarters if I can, but there is a passage through to the hospital courtyard, and we must carry her over if it’s necessary. But I don’t think it will be, now.”

Mr Burgrave nodded, and returned to his station on the west curtain. Why the enemy did not advance to the attack was a mystery. In the opinion of Ghulam Rasul and his most experienced subordinates, they had moved out from their position in the town, and were occupying the irrigated land on both sides of the canal in large numbers, sheltered against any volley from the walls by the rows of trees which marked the lines of the water-courses. They could not be seen, nor could it precisely be said that they were heard, but as the old soldiers in the garrison said, it could be felt that they were there. The situation was eerie in the extreme, and Mr Burgrave was unable to find comfort in a phenomenon which made his men cheerful in a moment. It was the Ressaldar who called his attention to it as they stood straining their ears in the attempt to distinguish some definite sound in the murmuring silence, and at once he himself heard clearly the faint tramp of a galloping horse far away to the north-east.

“He rides!” breathed Ghulam Rasul in an ecstasy, and “He rides!” cried the sowar nearest him, catching up the words from his lips. “He rides!” went from man to man, until the defenders of the towers looked at one another with glistening eyes, and even the unsympathetic Sikhs, who held themselves loftily aloof from the contemptible local superstitions of their Khemi comrades, repeated, with something of enthusiasm, “He rides!” “He rides; all is well,” said Ismail Bakhsh, puffing out his chest with pride, in his temporary guardroom on the clubhouse verandah. “Sinjāj Kīlin Sahib is watching over his house and over his children. The power of the Sarkar stands firm.”

“HE RIDES”

All unconscious of the moral reinforcement which was doubling the strength of the garrison, Mabel and Flora sat disconsolately over the charcoal brazier in Mrs Hardy’s room, listening for the sounds of the attack, which they expected to hear each moment. Mrs Hardy’s vigorous rebuke had nerved them both to put a brave face on matters, and for some time they vied with one another in discovering reasons for refusing to credit the report of the fugitive, and deciding that all might yet be well. But as time went on, and there was no sign of the triumphant return of Colonel Graham and his force, their valiant efforts at cheerfulness flagged perceptibly. Mrs Hardy, running across to say that Georgia was doing pretty well, advised them to lie down and try to sleep, but they scouted the idea with indignation, and still sat looking gloomily into the glowing embers and listening to the night wind, which wailed round the crazy old buildings in a peculiarly mournful manner.

“Doesn’t it seem absurdly incongruous,” said Mabel at last, in a low voice, “that you and I—two fin de siècle High School girls, who have taken up all the modern fads just like other people—should be sitting here, expecting every moment that a band of savages will break in and kill us—with swords? It feels so unnatural—so horribly out of drawing.”

“How can you talk such nonsense?” snapped Flora, upon whose nerves the strain of suspense was telling severely. “I never heard that a High School career protected people against a violent death. Do you think it felt natural to the women in the Mutiny to be killed—or the French Revolution, or any time like that?”

“I don’t know. It really seems as if they must have been more accustomed to horrors in those days. Just imagine, Flora, the little paragraph there will be in the South Central Magazine: ‘We regret to record the death of Miss Mabel North, O.S.C., who was murdered in the late rising on the Indian frontier. Miss Flora Graham, a distinguished student of St Scipio’s College, St Margarets, N.B., is believed to have perished on the same sad occasion.’ Your school paper will have just the same sort of thing in it, and the two editors will send each other complimentary copies, and acknowledge the courtesy in the next number. It will all be about you and me—and we shall be dead.”

“Of course we shall; you said that before. But I don’t see what good it does to die many times before our deaths.”

“How horrid of you to call me a coward!” said Mabel pensively.

“I don’t call you anything of the sort. I think you must be fearfully brave to look at things in this detached, artistic kind of way, but what’s the good of it? Death must come when it will come, but naturally no one could be expected to look forward with pleasure to the mere fact of dying. Unless, of course”—Flora’s blue eyes shone as she turned suddenly from the general to the particular—“my dying would save papa or Fred. Then I should be glad to die.”

“You really mean that you wouldn’t mind being killed if somehow it would save either of their lives?”

“Of course I do, just as you would gladly die to save your Eustace.”

“But I wouldn’t!” cried Mabel involuntarily, then tried to minimise the effect of her admission by turning it into a joke. “I think it’s his privilege to do that for me.”

“I wish you wouldn’t say that sort of thing!” said Flora reproachfully. “Happily there’s no one else to hear it, but if I didn’t know you, I should think you were perfectly horrid.”

“No, Flora, really,” cried Mabel, in a burst of honesty; “I can’t say confidently that there is one person in the world I would die for. I feel as if I could die to save Georgia, but I don’t know whether I could do it when the time came. I used to think that people—English people, at any rate—became heroic just as a matter of course when danger happened, but now I begin to believe that it depends a good deal on what they have been like before.”

“You always try to make the worst of yourself.”

“No, I don’t. I’m trying to look at myself as I really am. I have never in all my life done a thing I didn’t like if I could help it. What sort of preparation is that for being heroic? Flora,” with a sudden change of subject, “suppose the enemy had stormed the fort before this evening, would you have asked your father or Fred to kill you?”

“No,” was the unexpected reply. “It would have been so awfully hard on them. I keep a revolver in this pocket of my coat. You just put it to your eye—and it’s done.”

“Oh, I wish I was like you! I know I should be wondering and worrying whether it was right, and all that sort of thing, until it was too late to do it.”

“I don’t care whether it would be right or not,” said Flora doggedly. “I should do it. Do you think I would make things worse for papa and Fred, or let them have the blame of it if it was wrong?”

“I suppose Eustace would do it for me,” drearily. “He would if he thought it was the proper thing. He always does the proper thing.”

“I wish you wouldn’t talk in such a horrid voice. It makes me feel creepy. And I don’t think it’s fair to say that sort of thing about the Commissioner. He’s perfectly devoted to you, and you know it would break his heart to have to—do what we were talking about. I don’t believe you’re half as fond of him as he is of you.”

“Have you found that out now for the first time?”

“Then it’s a shame!” cried Flora. “Why do you let him think you care for him? He worships you, and you pretend——”

“I don’t pretend. He took it into his head that I cared for him, and wouldn’t let me say I didn’t. And he doesn’t worship me. He thinks that I shall make a nice adoring sort of worshipper for him when he has got me well in hand.”

“Well, I think you ought to be ashamed of yourself!” said Flora crushingly.

“You needn’t be horrid. I’m sure I have quite enough to bear as it is. What with thinking every morning when I wake that I shall have to be pleasant to him whenever he chooses to come and talk to me all day, when I should like to be at the other end of the world——”

“What do you mean to do when you are married?”

Mabel shivered. “I don’t know,” she said. “I rather hope we shall be killed instead.”

“You needn’t expect to get out of difficulties in that way. If you want to be killed, you are quite sure not to be. And to go on living a lie——”

“Don’t!” entreated Mabel. “Whichever way you look at it, it’s dreadful. I don’t know what to do. What’s that? I’m sure I heard a step.”

It must have been Mr Burgrave’s evil genius which prompted him to present himself at that particular time. The enemy had made no movement, and the Commissioner thought he might safely leave the wall for a moment, in order to obtain a sight of Mabel, and inquire after Georgia. He entered the room with a creditable assumption of cheerfulness, which the girls did not even observe.

“How are we getting on?” asked Mabel hastily.

“Oh, well, we must hope for the best,” was the unsatisfying answer. In his own mind Mr Burgrave had no doubt that the enemy were only waiting for dawn to make their attack, and would advance on the fort at the same moment that their guns opened fire from the hill.

“No news yet of the forlorn hope?” asked Flora.

“No news,” he answered, then hesitated with his hand on the door, and looked at Mabel. She rose, as if in response to his glance, and went out on the verandah with him.

“Poor little girl!” he said, putting his arm round her. “This waiting-time is very hard upon you, isn’t it? God knows I would give you comfort if I could, but I dare not raise false hopes.”

Mabel freed herself from his clasp. In the dim light cast by the brazier through the small window, he could see that she was very pale, and that her eyes looked unnaturally large and dark in the whiteness of her face. “I want you to take this back, please,” she said, holding out her engagement ring. “I can’t die with a lie upon my soul.”

“A lie