CHAPTER XVI

THE BEE RAFT

“A raft?” said Joe, astonished. “Nonsense, Sam. Why, it would take a raft as big as the whole bee-yard.”

“Plenty of dry cypress logs down yander, all ’long de bayou. We’d mighty soon make a big raft,” Sam persisted.

At this moment Bob also appeared out of the gloom, roused by the sound of talking.

“It mightn’t take such a big raft,” he said. “We could pack the hives close together. I believe Sam’s hit on something. Can’t we have a light?”

Joe thrust a few fragments of pine, and scraps of an old gum, sticky with wax and resin, into the fireplace, and struck a light. The leaky old cabin looked more cheerful as the flame flared up, and while the rain still roared on the roof they discussed the new scheme.

“Let’s figure how big a raft it would really take,” said Joe, taking a bit of pencil and a piece of smooth board. “A hive is sixteen by twenty inches square.”

A little calculation showed that the raft would need to be at least fifty feet long and twelve feet wide, to hold the bees, placed in four rows.

“But it’s only about thirty miles down to the place where we’d want to land them,” said Bob. “Then we’ll be only four miles from the railroad. Isn’t that right? I should think we could float that far in one day. The river runs smoothly, and the bees would hardly know they were being moved. I don’t think we’d even need to close the hives. It’s a lot better way than the steamboat, and then think of all the freight we’ll save.”

Sam chuckled jubilantly at this support.

“It’d be a big job to build that raft,” said Joe. “There’s plenty of timber and nails, to be sure, but what about lumber for joining and flooring it?”

“Tear this old cabin to pieces!” Bob exclaimed. “We won’t need it any more.”

“Good idea! That’ll certainly give us all the boards we want,” said Joe, and he laughed. “What a joke on Blue Bob, if he comes back here and finds the rosin, bees, and cabin all gone!”

The plan seemed more and more possible as they discussed it. The heavy rain ceased while they talked; the fire burned down, and they at last retired to their damp couches and slept. But they were up early in the morning, and, after a hasty breakfast, they went out to look over the resources of timber.

The morning was clear, and the sun came up brilliantly. The bayou had risen considerably with the rain and flowed with a muddy and perceptible current. As Sam had said, there were plenty of fallen cypress logs along the bayou, as well as dead standing trunks, and the sloping bank would make it easy to get them into the water.

“I vote that we try it,” said Joe at last. “It seems to be our only chance to get away with the bees. We’ll have to cut out the logs for the body of the raft first, and then pull down the cabin, rush the bees aboard, and start quick.”

Without any delay they set to work, with muscles that had scarcely recovered from the stiffness of loading the rosin. Unfortunately they had only one ax, but they kept that busy. For twenty minutes Sam chopped furiously, then passed the ax to Joe, who in turn relinquished it to Bob. Then, while one chopped, the others rolled logs into convenient places, and began to pull out nails from the cabin walls and make what other preparations they could.

By dinner-time they had cut up ten twelve-foot logs and rolled them down to the water. All that afternoon they toiled hard, and all the next day. They were haunted with the idea that Blue Bob and his men might return at this last, critical moment. The sound of the echoing ax was dangerous; it would surely draw the river-men if they were within hearing, and the boys kept nervously on the alert, never without a weapon at hand.

But they were not interrupted in any way, and in two days they had forty stout logs of dry cypress cut out, which, as Bob said, looked enough to float a church.

The next thing was to rip the boarding off the cabin. This was to be the final step, for it would deprive them of shelter. It was too late to make any progress with it that evening, however.

“This may be our last chance to sleep,” Bob remarked. “Let’s have supper and then make the most of a roof while we’ve got it.”

“Nothin’ much for supper ’ceptin’ corn-meal, an’ mighty little of that,” put in Sam, after inspecting the larder.

“Good thing we’re going to be away to-morrow,” said Joe. “Break into that stuff under the floor and get a ham. There’s no time to hunt or fish now, and we’ve got to have lots to eat, with all this heavy work.”

Sam delightedly broke into the robbers’ hoard in the “cellar” and unearthed a ham, from which he fried several large slices. It was a little musty, but it was better food than they had had for a day or two, and after devouring it they took Bob’s advice and slept soundly, all of them being extremely tired.

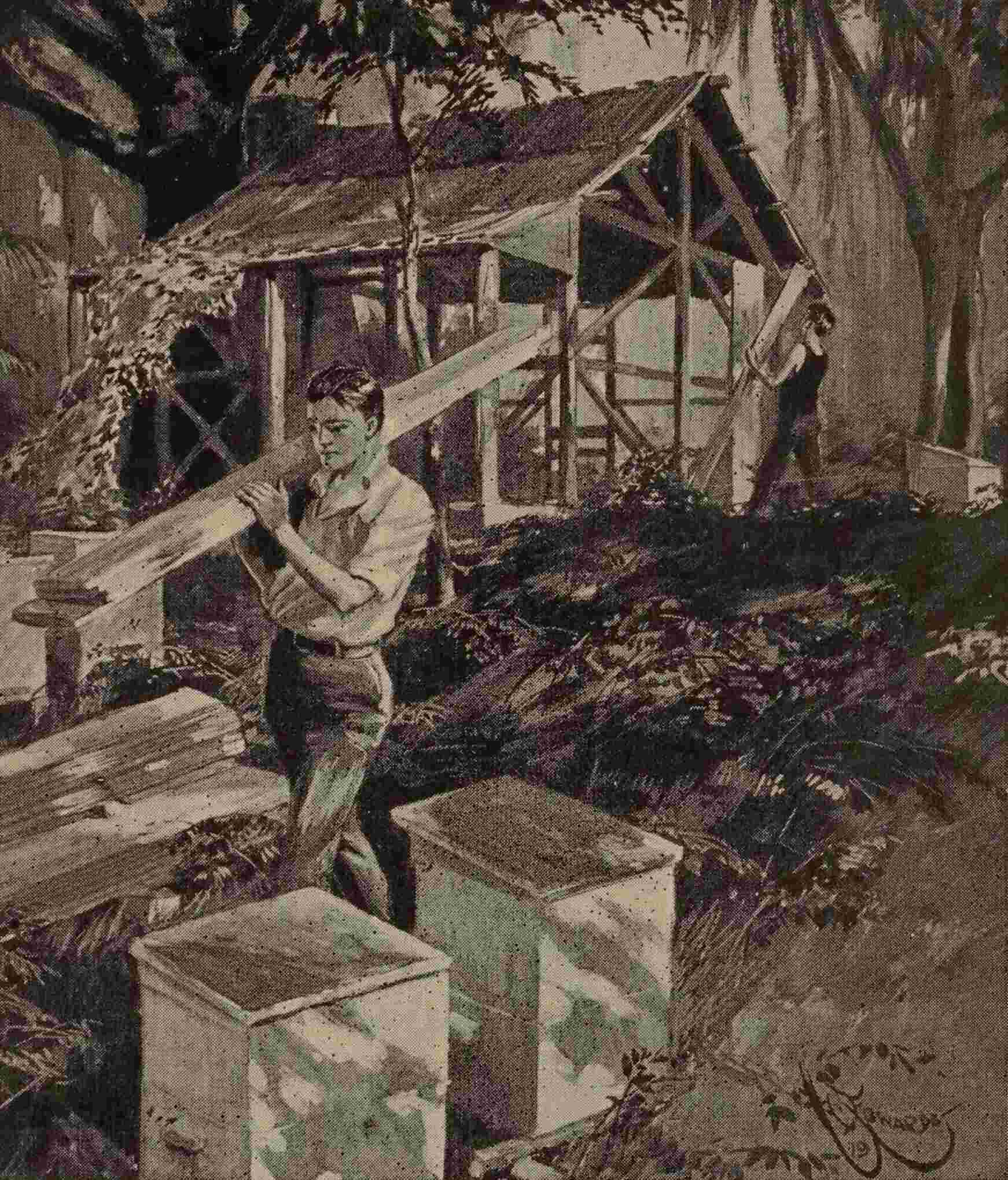

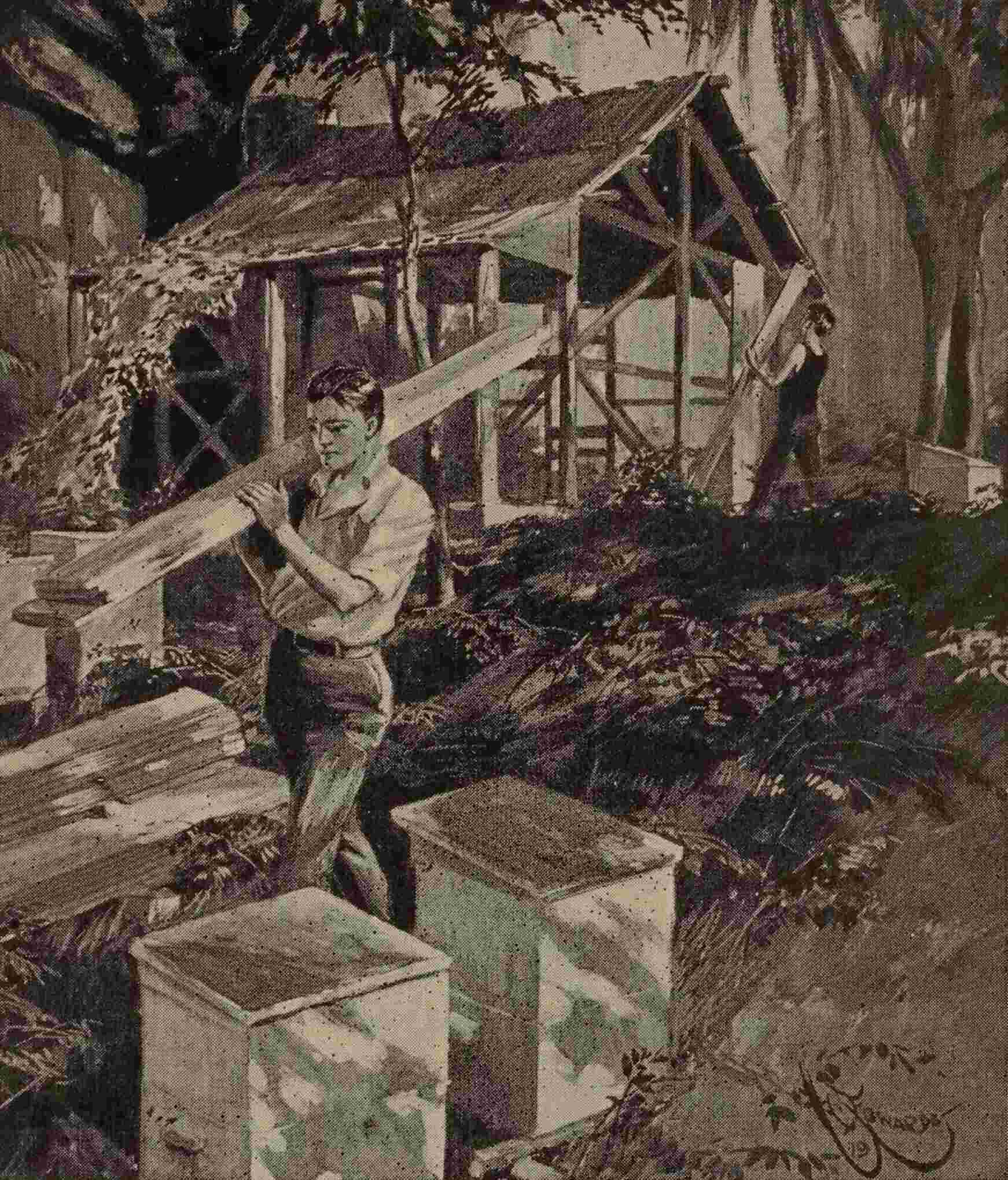

With the next daylight they began the work of tearing down Old Dick’s cabin. The boards were old, many of them were badly rotted, but most of them would serve in some way. Rapidly they ripped them off with ax and hammer, until the building that had been so useful to them was a mere skeleton. It was then noon; they cooked more of the stolen ham, and, growing reckless, Bob delved into the buried hoard and brought up a tin of biscuits and a can of tomatoes.

“We can keep track of what we use, and settle for it later with—with somebody,” he explained.

After eating, they laboriously carried the lumber down to the bayou, rolled half a dozen logs into the water, and began to put the raft together. It was a hot day, and the moist heat near the water was intense. Worried by mosquitoes and yellow-flies, soaked to the skin by constantly splashing into and out of the water, the boys labored and sweltered. They flung the boards across the logs and nailed them down as rapidly as possible, and the raft grew before their eyes. But it was going to be a bigger job than they had anticipated, and they had to stop at dark with only a third of the craft completed.

After seven hours of furious labor the next day they had laid all the flooring of the raft. Nothing was left now but to load the bees and the supplies; but they looked dubiously at the task of carrying more than a hundred two-story hives fifty yards down-hill to the water. It would take two of them to handle one hive, and they would have to walk slowly.

With the next daylight they began the work of tearing down Old Dick’s cabin

“Better sit down and rest for an hour,” Bob advised.

They did rest for half an hour, but, tired as they were, they were nervously impatient to finish. The end was in sight, but they might still be caught at any moment, and the whole enterprise collapse in disaster and possibly in bloodshed.

Since the honey was extracted, the hives were not extremely heavy, but they were awkward to handle. According to Bob’s suggestion, they had not closed the hive-entrances, and the bees had to be smoked to keep them from boiling out in a rage when their hives were lifted. It was with the greatest difficulty that they induced Sam to do his share of this ticklish and dangerous work; he was willing to carry double loads of anything else, but not bees; and, in fact, Joe and Bob did most of it. To preserve the balance they loaded the raft from each end, and by sunset a third of the apiary was on board. To their joy, the raft seemed to bear the weight buoyantly.

They rested for a little after supper, but they were determined to get the work finished that night, and they went at it again. Sam built a big blaze of pine and broken-up gums at the bee-yard and another beside the raft, where the bees murmured uneasily at the glare and disturbance. At eleven o’clock a hundred hives were aboard. Greatly encouraged now, they made coffee and rested for another half-hour; and by one o’clock every hive stood on the raft.

Carrying down their tools, bedding, and personal possessions, the honey extractor and the guns, they stowed them in the already crowded space.

“Got everything? Ready to go?” Joe demanded, gazing about the wreck of the cabin and apiary in the fire-glare.

“Got everything? Why, you-all ain’t a-goin’ leave all dis yere val’able stuff?” cried Sam wildly, indicating the pirates’ treasure that had been under the floor, now laid open to the sky.

“I don’t know. What do you say, Bob?” said Joe, undecidedly.

“Might as well take some of the most valuable stuff,” Bob advised, at which Sam gave a yell of delight. “Of course we’ll hand it over to the authorities when we get anywhere. It’s all marked with the name of the owner or shipper.”

Sam’s countenance fell heavily. However, they hastily picked out what appeared to be the most valuable portions of the stolen goods, put them into a couple of empty beehives, and carried them aboard. They fastened the rowboat by a scrap of rope to the stern of the raft. The flatboat would have to be left in the bayou; they had no further use for it. Sam brought buckets of water and put out the fires.

“All ready now. All aboard!” cried Joe.

He tried to push the raft off with a pole. It scarcely stirred. It seemed fast to the place as if anchored. All the boys heaved their weight on poles, and at last, inch by inch, they got the heavy affair away from the shore and out into the channel. But even there the current seemed hardly capable of moving it.

“This’ll never do!” Bob cried in alarm. “It’ll take us two days to get out of the bayou at this rate.”

“Heave hard on the poles,” said Joe.

They poled vigorously against the muddy bottom. It was a long time before their efforts had much perceptible result; but the big raft slowly gathered some speed, and at last attained a rate of something like a mile an hour.

It was a nervous period. It seemed impossible to work the speed any higher. The usual river mist had risen, making the woods and the water gray and indistinct. The boys sat on the bee-hives, hot, damp, alert, watching the trees crawl slowly past through the dim fog. It seemed to them that hours went by before a wider space showed dimly in front, and the head of the raft veered under a new current.

“The river at last!” muttered Joe, with immense relief.

They were really emerging into the Alabama. The boys fended off from the shore, fearful of sticking on the sand-bar as the raft slowly poked its nose out into the big river. Through the fog they could see little, but they could hear the rush and surge of the deep waters, running high with the heavy rain. They were fairly under way at last, and the anxiety began to fall from their minds.

But before the raft was entirely out of the bayou Bob suddenly gripped his cousin hard by the arm. Joe had heard it too, and so had Sam—the rattle and splash of oars up the stream. A boat was coming; it was invisible in the fog, but a few seconds later they heard a loud, reckless voice that they all recognized.

“Blue Bob! Oh, lordy! Now we’s sure ’nuff cotched!” Sam groaned.

“Hush!” Joe whispered, with a savage glance.

The boys crouched on the raft, scarcely daring to breathe, for their slowly-moving craft still blocked the mouth of the bayou. But fortunately the pirates’ boat was not so near as they imagined. Sound carries clear and far through fog, and the gray mist lay like a blanket on the water. The boys could not see from one end of the raft to the other; and they did not know for certain whether they were actually out until the raft began to show a brisker activity and to swing ponderously round in the Alabama current.

“What’s that?” said a voice that sounded scarce twenty feet distant. “I see somethin’ movin’ yander.”

The oars stopped. A faint blur showed through the fog. Joe noiselessly cocked his little rifle.

“Timber raft!” Blue Bob declared. “Blackburn’s gang has been raftin’ logs all the week down ter Mobile. I kin see it right plain.”

“Well, that’s what you reckon. I want to go an’ make shore,” returned another voice.

“Aw, shucks!” retorted the chief. “Nothin’ but a gang of river niggers aboard. We’ve got too heavy a load here to row back against this current.”

The stroke of the oars began again. The boat seemed to pass within a stone’s toss of the end of the raft, and the sound of rowing grew fainter up the bayou.

“Safe!” Bob ventured to whisper, after silence had fallen.

“I reckon so,” Joe murmured. “My hair almost turned gray for a minute. Luckily we put out those fires.”

“Yes-suh, Mr. Joe,” said Sam hoarsely. “But don’t you reckon dey’ll see right quick that we’ve done took de rosin an’ busted de cabin an’ moved de bees—an’ dey’ll be right after us?”

“They can’t see anything to-night,” returned Joe. “Likely they’ll sleep late to-morrow, and by noon we ought to be nearly at the end of our journey.”

“Besides, they’ll think we’ve gone by the steamboat,” said Bob, “and no use chasing us. They’ll never dream of a raft. I don’t believe they’ll give us any more trouble at all.”

They all tried to adopt this optimistic view. The raft was well out in the big river now, drifting at fair speed but proving quite unsteerable. The water was too deep to reach the bottom with the poles, and it was impossible to see anything ahead through the haze, so the boys were compelled to sit still upon the bee-hives, letting the raft drift, and trusting to blind luck to keep clear of sand-bars.

But the night was drawing to an end. Presently the fog paled and then reddened over in the east, and began to disperse. As the sun came up the drifting clouds split and melted; the boys saw themselves at last in the wide, yellow river, nearly in mid-channel, with low banks of intensely green swamp on both sides. The river was several hundred yards wide at this point, running fast with great surging eddies.

They were delighted to see how well the raft that they had built carried the weight of the hives. The flooring was dry; the hives stood a good four inches above the water. The framework seemed to hold together rigidly and strongly. Hardly a bee was in sight, though all the entrances were wide open. They had all crept inside, discomforted by the damp and by the steady swaying motion.

“How about breakfast?” Joe suggested.

“Just the thing,” said Bob. “I brought some of the stolen grub from the cabin. But we’ll have to eat raw ham, I guess, for we can’t build a fire here.”

“Why not?” Joe laughed, and he got into the small boat, rowed himself ashore, and overtook the raft with a bushel of sand and gravel and mud. With these materials they made a fireplace on the planking of the raft and ventured to kindle enough of a blaze to boil coffee and fry ham, putting it out immediately afterward, though Joe said that the timber rafts carry fires burning continually on a mud bed.

The food did them a great deal of good, and they began to feel much more cheerful. The sun shone brilliantly over the river, promising another hot day. The bees, warmed up, began to stir uneasily, crawling out, taking wing, and then returning, confused by the strangeness of the locality.

“I do believe they’re going to try to gather honey while they travel,” exclaimed Joe. “If they do, they’ll never get back to the raft again.”

But the intelligent insects were far too knowing to be thus caught. They flew about within a few yards of the hives, evidently looking the situation over. Then, deciding that conditions were far too mysterious and uncertain for work, they settled about the hive entrances in clusters and flew no more.

All through that forenoon the boys kept a watchful eye on the river behind them, continually in dread of seeing Blue Bob’s pursuing boat dart around a bend. But their apprehensions gradually diminished as time passed. The raft was making quite creditable speed now, for the current was unusually strong since the rain. The river wound and doubled on itself through the trees, always curving, always bordered by the dense swamps, gray with drooping Spanish moss. Twice they passed a solitary and deserted riverside warehouse—stopping-places for the boat. Once in a long time there was a patch of “bottom-land corn,” growing rankly in the rich mud; but the only human being they saw was a negro fisherman in a canoe. He was so stupefied by the sight of the big raft of bee-hives that he was incapable of even answering the boys’ hail.

The boys lounged back on their blankets and let the raft drift. Sam went soundly asleep on his back in the sun. It was pleasant to rest, for they had been under a great physical strain for days and had been cutting the nights short at both ends. But now they began to feel well on the way to safety, and they let the warm sun take the ache out of their sore muscles.

“The worst is over now,” said Bob. “We ought to be able to land the bees to-night. No fear of pursuit now, I guess. In a month from now we’ll have a car-load of bees up in Ontario, at Harman’s Corners, and we’ll all be independent for the rest of our lives.”

“You bet we will!” Joe responded with enthusiasm. “I’m going to learn the bee business for all I’m worth. With the money from the rosin and everything we ought to be on velvet, and I don’t see how we can possibly lose on the thing now.”

It was clear, however, that it would be late that evening before they could reach the spot where Joe counted on unloading the bees, whence they could be hauled across country to the railway. The river continued to unroll its endless, solitary windings. Wild ducks whirred up occasionally; once two small alligators flopped off the sand-bar into the water. Bob tried a little fishing but caught nothing. Sam was asleep again, and the two white boys finally lapsed into a doze.

They were sharply awakened by the raft touching on a hidden sand-bar, half grounding, and them swinging off, end for end. Startled by the jar, the bees were roaring and crawling out. The boys, scarcely less startled, sprang to the poles to push off, but the danger was already over, and the raft was under way again.

“That won’t do!” exclaimed Joe. “We must keep better watch than that. The river’s falling now; it may be a foot lower by morning, and if we’d got hung on that bar we might never have got off.”

For the rest of that afternoon they slept no more, but kept on the lookout for dangerous shallows. The raft did not ground again, but once it went over a submerged snag with a grinding jar that set all the bees rushing out. The collision might have ripped the bottom out of a boat, but the raft was unsinkable.

The sun went down over the swamps, and Sam lighted the fire again on the bed of sand and prepared supper. Mosquitoes began to be bad; a cool dampness, full of the smell of rotting vegetation, rose from the water. But it did not look as if there was going to be any fog that night, and they were determined to keep on as long as they could see. It could not be many miles, Joe thought, to their destination.

So they kept on through the twilight. It was almost dark when the raft went round a bend, and, carried by the shoot of the cross-current, went straight for the other shore, where a long peninsula extended, piled with a rick of dead drift-timber.

“Steer her! Fend off!” Joe shouted, but the momentum was too great. Nor would the poles touch bottom, and the raft ran heavily into something, recoiled, and swung sideways into the mass of fallen trees. There was a tremendous rending and crashing, and for a moment the heavy craft seemed likely to sweep the obstruction away. Then it slackened, the snapping of twigs ceased. The raft stood motionless, with the river current surging under its timbers. There was a great roaring from the troubled bees.

“Hung up for sure!” said Bob, peering through the twilight at the tangle of dead branches. “We’ll have to chop and saw all that stuff clear. It’ll be an all-night job.”

They were close to the shore, and mosquitoes began to swarm out in vicious hordes. Slapping at the pests, the boys in perplexity tried to examine the trap they were in by the light of splinters of blazing pine.

“I vote we go ashore somewhere and camp,” Joe suggested. “We can’t do this job in the dark. The mosquitoes’ll eat us alive if we stay here all night, and we might get a dose of chills and fever besides. Let’s go back to high ground.”

“Think it’s safe?” Bob asked, doubtfully.

“Of course. The raft can’t get loose, and nobody is going to touch it. We must be far out of Blue Bob’s range now. We’d have seen him before if he’d been after us.”

The others were willing to be persuaded, and they put the blankets and guns into the boat and went ashore. It was hard to find a spot dry enough to land. They got involved in a swamp, groped through fifty yards of mud and jungle, and came at last to rising “hammock-land.” A hundred yards further the ground was still higher, and a bare, open space seemed to promise comparative freedom from mosquitoes. It was so warm that they needed no fire; they spread their blankets on the bare ground and went promptly asleep.

Nothing disturbed them during the night, and they slept late, making up for their lately broken rests. The sun was well up when they awoke, and the night fog was thinning on the river. They were chilly and wet with dew as they tramped stiffly down to the shore, found their boat, and started to row down to the raft. There was still a drifting haze on the water. It was impossible to see clearly to the opposite bank, but the long point at the river bend, the rick of dead driftwood, was plain enough. But—

They let the boat drift, staring incredulously.

“Oh, Joe!” cried Bob in a heart-broken voice.

The tangle of drift had been pried and cut apart. The raft was no longer there.