CHAPTER I

WRECK IN THE WOODS

Leaning from his saddle, Joe Marshall looked into the cup that hung on the turpentine-tree. One side of the great long-leaf pine had been stripped of its bark to a height of three feet, leaving a tall, livid scar, sticky with resinous exudation. A thick layer of hardened gum crusted over its lower edge, and two tin gutters near the top carried the gummy oozings into the two-quart tin cup suspended from a hook driven into the tree. It was only March, but the weather had been unusually warm, and the gum was running in thin viscous threads imperceptibly slow, but the cup was half full of the sticky whitish mass.

“I declare, we can begin dipping soon!” Joe said to himself, glancing around at the other pines, which were all similarly blazed and tapped.

This was the best corner of the Burnam turpentine “orchard.” The trees that grew here were splendid long-leaf pines, shooting up straight as arrows almost a hundred feet before they broke into palm-like branches; and many of them were so large that the turpentine gatherers had been able to chip them on both sides, and hang two cups on them.

For about two hundred yards this park-like growth lasted, where his horse’s feet trod silently on the thick layer of pine-needles; then a slight descent took him out into the open ground. The sunlight seemed blinding after the shade of the woods. The sky was hazily blue, radiating an intense heat. High overhead two buzzards soared in circles. The ground was a tangle of gallberry-bushes, and Joe rode through them by a trail that he followed daily on his rounds. From the gallberry flat it led down to a creek swamp, dense with titi and bay-trees and tangled with bamboo-vine, and it wound through this jungle across the creek itself.

“Want to drink, Snowball?” said Joe, as the black horse showed an inclination to pause at the clear water; and while Snowball drank Joe dismounted and dashed water over his face and arms. It was unusually hot for March, even in southern Alabama, and from the look of the sky he judged that there might be thunder before night.

Joe was one of Burnam’s three woods-riders, and it was his duty to keep his eye on the run of gum and the work of the negroes on a third of the big tract. As he rode on he encountered several of the “chippers” at work, making the regular enlargement of the blaze on the pine-bark; occasionally he found a tree neglected, and had to find the man in whose “furrow” it lay, reprimand him, and send him back; now and then he had to stop and readjust a cup that had become displaced. Once he found two negroes idling and swapping stories behind a thicket, and he sent them back to work with good-natured bullying, which they took with equal good nature. They understood Joe Marshall, and he understood them.

He swung through the woods in a wide circle that would at last take him back to the camp. It was growing late in the afternoon, and most of the negroes were also straggling out of the woods. Provided they finished their furrow, they could leave when they pleased; but from the top of a ridge Joe caught sight of a chipper still at work, going at a fast trot from tree to tree. His clothes were ragged and there were not many of them; his arms were bare, and his black face streamed with perspiration. He carried a “turpentine-hack,” a tool very like a small pick with a keen, gouging end, and at each tree he ripped away with a skilful stroke another inch of the gummy bark at the top of the slash.

“Seems to me you’re working mighty hard for a hot day, Sam,” Joe remarked as he rode up.

The chipper threw back his head and laughed loudly. Sam was one of the “Marshall negroes.” His father had been a slave, owned by Joe’s grandfather, and Joe and Sam had both been born on the Marshall estate, before the place was broken up. They were about the same age and had played together as white and negro children will. Sam had been Joe’s lieutenant in many a hunting and fishing expedition, and when Joe had taken this place as woods-rider Sam had come as chipper in order to work in the woods with him.

“Yes-suh, Mr. Joe!” he cried, “I shorely is hot, but I reckon de weather goin’ change, an’ I wants to finish my furrow. Jus’ you look down yander in de souf. What you reckon comin’ up dere, Mr. Joe?”

“Thunderstorm, maybe,” said Joe, looking at the haze over the sky, and the coppery clouds low in the south, rising out of the Mexican Gulf. Sam looked too, intent, seeming to sniff the air, and his eyes looked suddenly wise and far-seeing, like a wild animal’s.

“I dunno, suh. Some kind o’ storm, shore. Anyhow, I’s goin’ mek for camp soon’s I finish my few mo’ trees. Mr. Joe, you better ride back home.”

“Oh, a thunderstorm won’t hurt us,” said Joe, laughing, and he rode on, intending to finish his usual round. He was anxious to give especial attention to his tract that day, for the next three days were to be a vacation. The other two wood-riders had agreed to look after his duties, and he was going to ride over to Uncle Louis’s plantation, ten miles south, to meet his cousins from Canada.

He had never seen these cousins—Carl, Bob, and Alice Harman—children of his father’s sister who had married a Canadian, for they had never been south before, and he had never been north of Tennessee. Both their parents had been dead for some years. The three lived together, and, Joe understood, were in bee-keeping. It seemed to Joe an odd and shiftless sort of pursuit, especially in the land of snow and ice which he dimly conceived Canada to be. They had been in Alabama now for several weeks, and had been ten days at Uncle Louis’s place, where they were to remain till spring. Joe understood that they were looking for more bees, and he chuckled at the idea. He knew where there were at least a dozen bee-trees. “Reckon I can show ’em all the bees they want!” he reflected. He had planned great entertainments for them. He would take them fishing for the giant Alabama catfish, take them ’possum hunting, show them the turpentine woods.

He rode on his wide curve through the pines, looking after the turpentine-cups, thinking of the Canadian visitors, when he suddenly became aware that the sun had disappeared. Glancing up through the feathery pine crests he saw a huge bank of tumbled, coppery-black clouds rolling up fast from the south. The air seemed dead still, but a chill had come into it. Far away he heard a growl of thunder, still faint and distant, and Snowball tossed his head, snorted, and stamped, looking back nervously at his master.

It was not the usual time of the year for tornadoes, but he knew how terrific these Gulf thunderstorms sometimes are, and he did not want to be caught in the pine woods where any tall tree might draw the flash. But he remembered a bare, open flat not half a mile away, and, kicking Snowball in the ribs, he started through the woods at a reckless gallop, over logs and brush without ever swerving.

A wind rushed heavily over the trees, carrying a curtain of black cloud. Twilight seemed to fall in a single instant. Snowball was almost uncontrollable with fright, but he saw the open space ahead. As he tore out of the woods, Joe saw behind them a wall of blackness sweeping up the sky with an appalling roar. He jumped from the horse, scared, uncertain what to do, knowing well now that this was no mere thunderstorm. Snowball reared, jerking the bridle from Joe’s hand, and bolted. The next moment the storm burst.

The sheer force of the wind swept Joe off his feet and rolled him over and over. The air was thick with torn pine-needles, flying branches, and strips of bark; trees were crashing and rending, and there was an uproar as if a giant were treading down the forest like grass. Rain suddenly came down in a blinding torrent. Half dazed, Joe tried to get to his feet, made a staggering run without knowing where he went.

A sheet of bluish lightning seemed to explode just over the tree-tops. In the midst of the deafening thunder a great pine snapped at the butt, not a hundred feet away. Joe heard the roaring swish as it came down through the air, straight towards him. He made a plunge to get away, but stumbled; and the next instant he was struck down in a whirl of snapping branches.

That was the last he knew for several minutes at least. When he came to his senses, rain was still pouring down upon him. The ground was streaming with water; a cold river seemed running under his back. The wind still blew fiercely but the lightning was more distant, and the worst of the storm seemed to have passed. He had no idea how long he had lain there, but the darkness now seemed to be, not of the storm, but of night.

He endeavored to raise himself, and found that something held him down with apparently enormous weight. It hurt, too; there was a pain in his chest, a sharp pain in his head. Dimly Joe imagined that the tree had fallen on him, and that he must be seriously wounded; but by groping with his hands he found that the trunk of the big pine had missed his body by a scant yard. His last jump had just saved his life, but one of the smaller branches had caught him across the body and pinned him down, though the mass of twigs had saved him from being crushed. Something had hit him on the head, too, but as he gradually came to himself he decided that he was not as badly broken to pieces as he had imagined. But for all his efforts, he could not work his way out from under the branch that pinned him fast down.

He wormed himself this way and that; he tried to hollow out the earth under him, until he had exhausted his strength. Then he shouted at the top of his voice, but in that roar of wind and splash of rain he knew that there was scarcely a chance of any one’s hearing him. Nearly all the men had left the woods.

The rain ceased to fall in torrents, slackening to a drizzle. The thunder already sounded far away. The storm was passing over as swiftly as it had come up. It had grown almost completely dark when at last Joe heard the far-away voice of a negro calling, echoing strangely through the woods. He yelled in answer; the voice approached; and presently he heard some one crashing through the bushes.

“Who dat a-callin’?” he heard a well-known voice. “Where is you?”

“Sam!” shouted Joe in delight. “Here—this way! I’m down under a tree.”

Sam appeared, a vague black shape in the blackness.

“Fo’ de land’s sake, Mr. Joe!” he exclaimed. “How you git dere? Is you hurted bad? Wait—I git you out!”

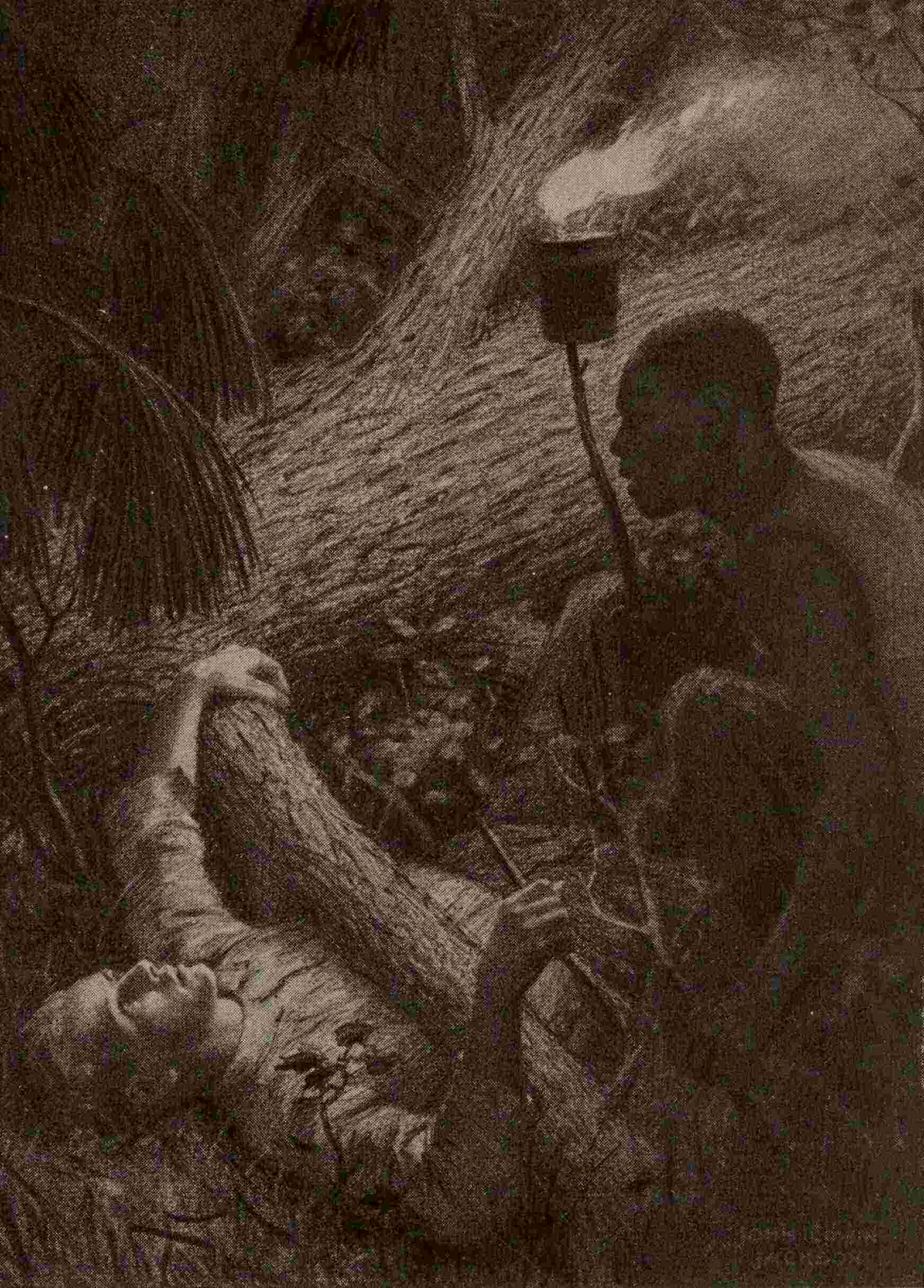

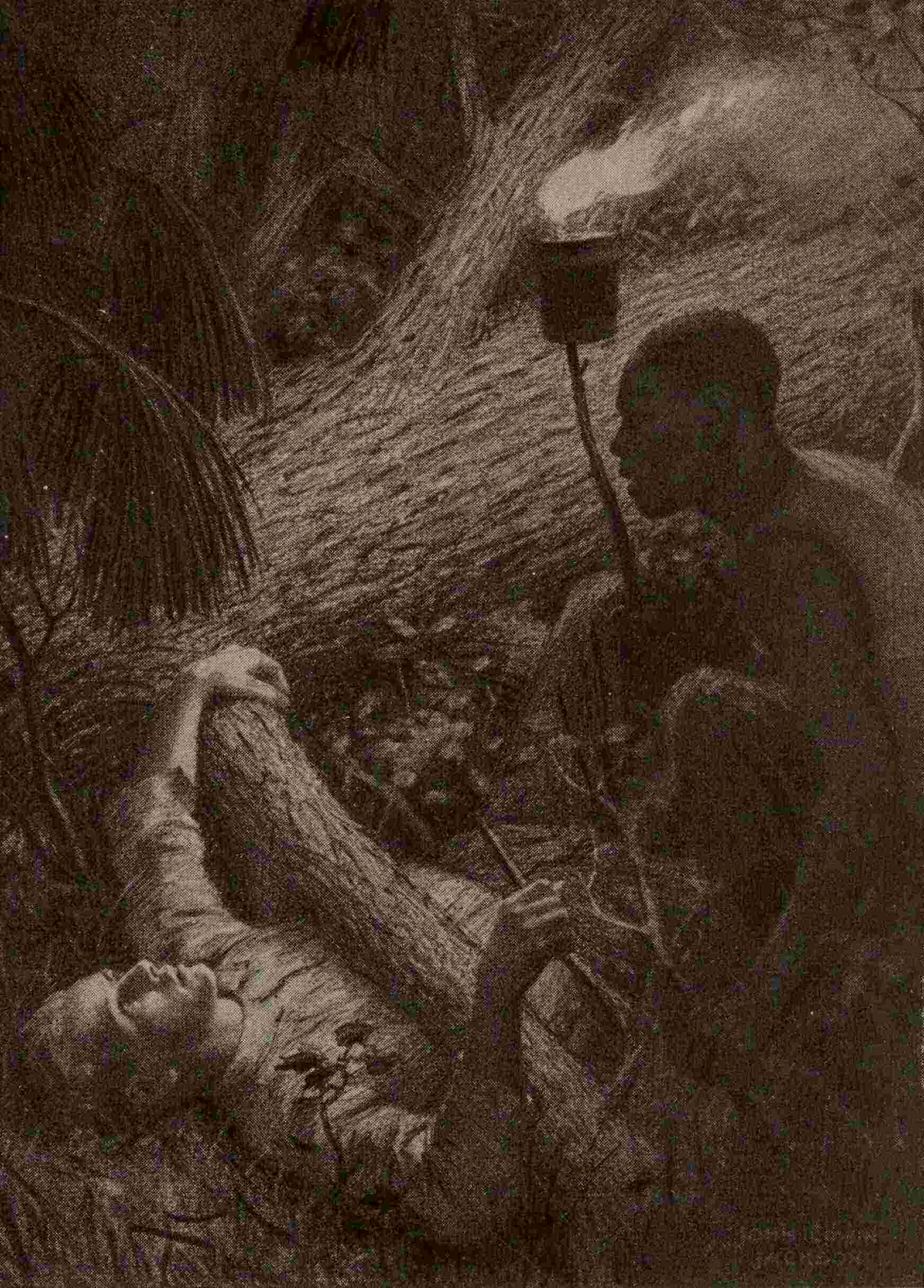

Sam pulled and hauled, aiding Joe’s fresh efforts. He tried to shift the branch in vain, and it was too dark to see what he was about. Presently he stopped, groped about in the dark for some time, and then, squatting in a sheltered spot, began to scratch matches.

By its light he was able to find a strong enough piece of wood for a lever

They were damp, and it was some time before he produced a flame. Then there was a sizzle, a flash, and a brilliant flare sprang up. Sam had found a cup half full of gum, and stuck the match down into the resinous stuff. It flamed up like a huge torch, blown in the wind, casting a lurid light on the chaos of the fallen timber, and Sam elevated it on a stick where it would illuminate his proceedings.

By its light he was able to find a strong enough piece of wood for a lever, which he inserted under the pine branch, and he raised it just enough to let Joe wriggle out. The negro solicitously looked him over; Joe felt himself anxiously, but he could not find any worse damage than a few bruises and a slight cut on the head just above his ear.

“No bones broken, Sam,” he said. “I’ll be all right now in no time. But why weren’t you back at camp?”

“Couldn’t mek it,” said Sam. “De big wind cotched me in de woods, an’ I just crawled under a log an’ laid still, scared most to death. Seemed like all de woods was goin’ down, an’ I reckon de best of ’em is down. Where de turpentine goin’ to come from now? Say, Mr. Joe, don’t you reckon dis de end of Mr. Burnam’s turpentine camp?”

The same question had already occurred to Joe and troubled him. It meant a great deal.

“I don’t know, Sam,” he answered rather irritably. “Let’s try to get back to camp and see how things are there. Do you know where we are? I feel dizzy and turned around.”

“Yessuh, Mr. Joe, I shore knows de way!” cried Sam with a loud burst of laughter. “I’s a piney-woods nigger, I is. Bawn an’ raised right in dese hyar woods. Couldn’t lose my way here no-ways, no suh, capt’n!”

To show his confidence he started at once, conducting his young master with one hand and holding the flaring torch with the other. It was hard traveling. The ground was covered with trees, large and small, blown criss-cross in every direction, and Joe’s heart sank more and more at the sight of the destruction of the turpentine pines.

For he was not merely an employee of Burnam’s camp. He was a shareholder. Everything he possessed in the world was tied up in that turpentine business. At the death of his father he had inherited a little money, placed in the hands of Uncle Louis as trustee and guardian. As he grew out of boyhood Joe had formed the plan of entering the turpentine business, a commerce which had been familiar to him from childhood, and Uncle Louis had invested the capital in the new camp which Burnam was starting. Joe went in as woods-rider, and it was supposed to be a good job and a safe investment. Burnam was well known as a successful operator, and the business promised a good return.

Uncle Louis, however, had carelessly failed to ascertain Burnam’s financial responsibility. He was thought to be solid; but of late Joe had heard rumors that the camp had been started on a little money borrowed here and there like his own, and that it was now being carried mainly by the bank. Instead of a good investment it was a shaky speculation. Burnam was a skilful and experienced turpentine man. With luck he might pull through successfully: but a stroke of misfortune would be likely to put him into bankruptcy. And it looked as if that stroke had come.

Sam burned two or three more cups of gum before they finally came out of the wrecked woods, and sighted the camp, built a hundred yards back from the main road that led in from the river landing. From a distance they could see a swarming and rushing of torches, and hear the voices of men, but the camp did not seem to be demolished as he had feared. It was less a camp than a small village of nearly fifty negro cabins and dwellings for the white officers, built in a hollow square around the turpentine-still, the cooper-shop, the storehouse, and the commissary-store. The road and the square were running with water, but everybody was out, and, to Joe’s relief, he saw that the buildings seemed to be intact.

Just at the edge of the camp he met Tom Morris, one of the other woods-riders.

“Gracious, Joe!” he exclaimed. “You look as if you’d been through a mill. Snowball came in half an hour ago, covered with mud and scared to death. Your saddle and rifle were on him, and we thought you’d sure gone up. We were just getting ready to go out to look for you. How are the woods?”

“Smashed up. How’s the camp?”

“No damage to speak of. The still’s all right, by good luck. The roofs of two or three cabins blew off, but the main track of the storm went a little west of us. But, say! isn’t this going to hit Burnam pretty hard?”

“Afraid so, Tom,” said Joe seriously. He did not want to discuss the matter; he felt too sore and uneasy. He avoided Burnam, who was hurrying about with Wilson, the camp foreman, to ascertain the damage. He went to look at Snowball, whom one of the negroes had unsaddled and brushed down a little, and then he slipped into his room at Wilson’s house, where all the woods-riders boarded. He went to bed, intensely tired and aching, intending to think it all over; but he was scarcely there when he fell soundly asleep.

It was a little late when he awoke, to find brilliant sunshine at the windows. Morris, who shared his room, had already gone. Joe still felt somewhat stiff and sore, but he dressed and quickly went out.

The sky was as clear as if there had never been a storm, and the air was full of sparkle and lightness. The hard sand of the camp square was dry and firm already; the surrounding pines were a fresh-washed, vivid green. There were not many signs of the tempest visible here—only an unroofed cabin or two, a pine that had fallen right into the camp area, and the brook beside the road that flowed muddy and bank-full.

The routine of the camp was disorganized that morning. Negro women and children swarmed about the cabins, calling to one another; the chippers from the wrecked area loafed in the sun, smoking cigarettes, waiting for orders. Joe found Tom Morris near the still, talking with the foreman.

“I was waiting for you, Joe,” said the rider. “Feel all right this morning? Burnam was up at daylight and rode off to look at the woods. He left word for you and me to go over your tract and report. Had your breakfast? Well, go get it quick.”

Joe hurried over the meal, had Snowball brought round, and they rode off, Wilson going with them. The former wagon-trail into the woods was badly choked with fallen timber; they had to make continual detours, and pick their way among the pines. The big turpentine tract lay in a rough rectangle north and south, and the storm, passing right down the middle, had raked it from end to end. The magnificent pines strewed the ground, were broken off at mid-height, stood leaning against one another, ready to fall at the next wind. Some of the gum-cups still clung to the trees; others lay scattered over the ground, spilling their thick contents. They rode through this scene of wreck for a mile or two, and then Wilson stopped his horse.

“I don’t want to see no more, boys,” he announced. “Looks to me like this camp’s plumb ruined. I reckon we’ll all have to hunt another job right soon.”

“Oh, I don’t know,” said Morris, encouragingly. “It ain’t all as bad as right here. And then, Burnam’s got the river orchard.”

The river orchard was a tract of about five hundred acres lying close to the Alabama River, three miles away. The remainder of the turpentine woods had been merely leased for three years, but this tract belonged to Burnam outright. He had never turpentined it, because the tapping of the trees materially injures them for timber.

“Burnam won’t turpentine the river orchard,” said Wilson. “He’s saving it for timber.”

“Well,” he continued, after a gloomy pause, “I s’pose I’d better go back to camp and get some niggers and gather up these here cups. Better save what we can.”

For two or three hours Joe and Morris rode through the woods, finding it a depressing spectacle. In the direct track of the storm, fortunately not very wide, it looked as if hardly anything was left fit to turpentine. Outside that belt the damage was not so great, but the woods were so choked with fallen trees and debris that it would take weeks of labor, it seemed, to clear them enough to carry on operations.

“I was going off on a holiday to-day,” Joe remarked. “I reckon that’s indefinitely postponed.”

“I don’t see why,” Morris returned. “This is just the time. There won’t be much woods-riding done for a week. The men’ll all be busy clearing up the mess.”

“Well, I’ll see what Burnam thinks. I want to talk to him anyway,” said Joe. “I’ve got to find out if this camp is busted or not.”

Burnam had come in by the time the riders got back, and Joe found him in his little office in the rear of the commissary-store, bending over a heap of papers and looking worried. The turpentine operator was past middle age, tall, spare, and wiry, burned brown by the Alabama sun. He had spent all his life among the pines, working in turpentine and rosin and lumber; he had a reputation for success and luck and for generosity and for a violent and uncontrollable temper. He had been known to draw a gun on one of his men, threaten him with death, discharge him and be ready to forget it all the next day. He was dressed as he had come in from riding, in flannel shirt and khaki leggings; his soft black hat was pushed on the back of his head, and he met Joe’s entrance with a glance of irritation. He was in no smooth temper, but neither was Joe.

“Morris and I have looked over most of the tract, Mr. Burnam,” Joe began. “Nearly half the timber looks to be down, or all tangled up. We can save a lot of gum by gathering up the cups right away, but everything is in bad shape.”

Burnam said nothing, but frowned as if he knew this already.

“Is the camp going to go on, or shut down?” Joe ventured.

“That’s my business!” Burnam snapped.

“Mine, too. You’re forgetting that all my money is tied up in this outfit. It was supposed to be a good investment.”

“Well, ain’t you getting ten per cent. on it?” Burnam demanded.

“Yes—so far. But will I ever get the principal back?”

Burnam gave him a furious glance. For a moment Joe expected one of the turpentine man’s famous explosions of rage; but then Burnam leaned back in his seat, took off his hat and put it on the table, and grinned.

“I don’t blame you much for being worried, Joe,” he said. “You can bet that I’m worried myself. But I’ll pull through. I’m going to turpentine the river orchard.”

“All right,” said Joe, surprised and relieved. “Do you want me to ride it?”

“Sure. I hadn’t intended to turpentine that tract, but now I’ve got to. I was looking over it this morning, and there’s right smart of good pine there.”

“All right,” said Joe. “I’ll do the best I can—I’ll work like any nigger—for myself as well as for you.”

“I reckon you’ll pull us through, then,” returned Burnam, with some dryness. “You were fixing to take a few days off now, I think.”

“I was—but of course I won’t now,” Joe hastened to say. “I wouldn’t leave the camp in this fix.”

“No, that’ll be all right. For the rest of this week the men’ll be doing nothing but clearing up fallen timber. You go and visit with your kin-folks for three days if you like; we can spare you as well as not. I can’t let you have the car to-day, but to-morrow’s boat day, and you can ride down to the landing and take your horse with you on the boat.”

Joe had no hesitation about accepting this offer. He had been looking forward to seeing his Canadian cousins, and now he particularly wanted to talk to Uncle Louis about the financial prospect. He knew that Burnam would not let him go unless he could really be well spared, and he thanked the turpentine operator and went out, feeling as if he had been treated with more generosity than he deserved.

The rest of that day he spent with Morris and Wilson, setting the negroes at clearing up the woods, collecting the scattered gum-cups, opening trails for the wagons again, and planning to get what turpentine could still be obtained from the wrecked “orchard.”

While he was still at breakfast the next morning he heard the deep roar of the river-steamer’s whistle resounding tremendously through the woods. There was no hurry; she was still far away, for her great siren would carry fifteen miles in calm weather; but as soon as he could finish eating he jumped on Snowball and rode at a gallop from the camp and down the road to the landing.

It was three miles to the landing. The road, of yellow sand and clay, had already dried hard since the rain, and it ran between banks of brilliantly-colored clay, vermilion and greenish and white like striped marble. A rivulet of clear water ran on each side of the road, and on each side rose the vivid green of the pines. As he approached the end he passed through a belt of dense swamp, a tangle of creepers and thorns and titi-shrubs and bay-trees, and then he came in sight of the Alabama River.

There was no wharf, merely a freight warehouse and a cotton-shed at the landing, and three or four men were already there looking out for the boat. The river was a quarter of a mile wide here, running full and strong after the heavy rain, wallowing around its great curves, muddy and opalescent. Down to the water’s edge the shores were densely wooded with sycamore and willow and cypress, overrun with yellow jessamine and hung with gray Spanish moss, and, except for the freight-shed, the scene must have been exactly as it had been when the first Spanish explorers came up from the Gulf to look for the fabled Indian treasure-cities.

The steamboat’s whistle roared again, perhaps four or five miles away. As Joe rode up to the landing he saw a black object drifting slowly down the river. It was a houseboat—a flatboat with a rough cabin that covered the whole deck, except for a small deck-space at each end. It was painted or tarred a rusty black; it looked heavy in the water, and it moved sluggishly. A big steering-sweep trailed idly astern, and no one showed his face aboard her.

Joe had seen many such houseboats before. There is a migratory population using them upon all the large rivers of the South; but the somber appearance of this one caught his attention. It looked vaguely sinister to him.