IV

MOODS of the night pass with their tragic glooms, and the first lines of sorrow fade into dull distaste and distant apprehension. Husband and wife met day by day, and slowly the black cloud between them became imperceptibly mist: the man dared raise his eyes to that pitiable face, and the silent wife began to speak. Doctors had come and applied their poultices against panic,—the vast circle of probabilities, the excellences of regimen.

Then the engineer, in the fulfilment of his business engagements, had gone away for six weeks, which the mother and child had spent at the seacoast for a change of air. Early in September they were living once more in the pleasant country house outside the great city, and husband and wife were talking almost confidently of what they should do in this matter and that, speaking with more and more certainty as the days slipped past. Something grave in the woman’s voice, a touch of doubt in the glance between them—those signs alone remained, and the memory.

Another trip to the mines was to be made; the date of departure Simmons put off, in order that he might take his wife to the large dance at the Bellflowers’. On this day he returned from the city by an early afternoon train. When the coachman drew up before the house, no one could be seen about the place. Simmons called out heartily:

“I say, where are you? Is any one about? Evelyn!”

Windows and doors were open; the summer wind blew through the house. There was a vacancy about it all which impressed the man.

“There was somethin’ or other goin’ on when I hitched up,” the coachman ventured to remark. “There were a lot of hollerin’ and screamin’, sir; somethin’ up with the children.”

He had the air of being able to tell more if necessary. Mr. Simmons jumped to the ground and entered the house. A servant, who finally appeared in answer to his repeated calls, told him that she had seen Mrs. Simmons crossing the meadow below the lawn, in the direction of the little river at the bottom of the grounds. She had little Oscar with her, so said the maid, and she seemed to be hurrying.

He hastened to the little boat-house on the river. Hot summer afternoons it was a common thing for his wife to row upon the river, yet every moment he quickened his steps until he was on the run. From the meadow wall he could see his boat tied to a stake in the stream, riding tranquilly. Evelyn was not on the river. He followed the foot-path, hesitatingly, beside the sluggish stream, calling in a voice which he tried to make quite natural:

“Evelyn! Oscar! Evelyn—where are you?”

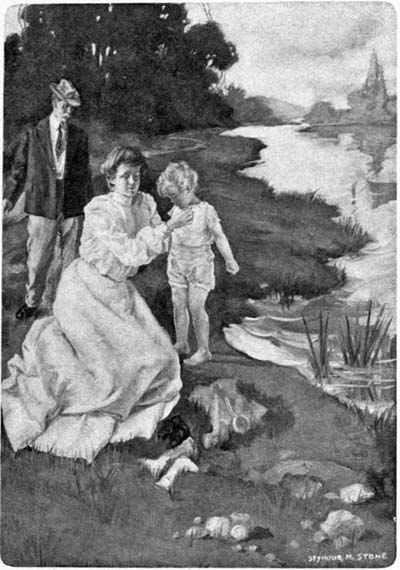

There was a yard or two of sandy beach beside the boat-house, and there he found them. His wife was kneeling down on the sand, her face to the river, engaged in hurriedly undressing the child. She had him almost stripped of his clothes, and she was talking to him, while he listened with the attention, the thoughtfulness, of a man. Suddenly spying his father, he laughed and broke from his mother’s arms.

“There’s Dad!” he cried. “Are you going away, too, with mamma and me? She’s going to take me far out into the river, away and away, and we are never coming back any more, never going to play any more up there on the lawn!”

His voice rose in the childish treble of wonder, and he added, after a moment:

“HIS WIFE WAS ... HURRIEDLY UNDRESSING

THE CHILD.”

“Now you come, too, Dad.”

“Evelyn! What does this mean?”

She had risen hastily when little Oscar called out to his father. Her eyes were red with tears, and her hands shook with nervousness.

“I thought it would be all done, all over, before you came,” she murmured. “But he would not come with me unless I took off his clothes. I tried to take him in my arms, but he broke away.”

The man shuddered as he gradually comprehended what it meant. Little Oscar ran back to his mother and put his face close to hers.

“Mamma is sick,” he said gently. “You must take her home and put her to bed and have Dora sing to her.”

His lithe little body danced up and down. The hot wind waved his black curls around his neck. His mother pushed him away.

“Take him,” she groaned. “It kills me to look at him.”

Simmons gathered up the child’s clothes and began to put them on the dancing figure.

“What has crazed you?” he demanded roughly of his wife.

“I will tell you—when he is gone,” she answered wearily, leaning her head against the shingled wall of the boat-house.

Little Oscar ran to and fro in his drawers, wet the tips of his feet, and threw sand into the water, while his father was trying to dress him. Finally the mother took the child, put on his shirt, and told him to run home. He dashed into the thicket of alders beside the river with a shout. Soon they heard his voice in the meadow, ringing with the joy of living, the animal utterance of life.

“It was this afternoon,” the mother explained. “The Porters’ children and the Boyces’ boy were playing on the terrace. Dora was away. I was reading in my bedroom—I had told Dora I would look after the children. I must have dropped asleep with the heat—perhaps a minute, perhaps longer. Suddenly, I felt something fearful. I seemed to hear a choking, a gurgling. When I jumped up, awake, everything was still, quiet,—too quiet, I thought; and I ran to the window over the terrace.”

She covered her face with her hands to shut out the sight of it, and the rest came brokenly through her smothered lips:

“Oscar was there—he and little Ned Boyce. Ned was lying—down on the brick floor—and Oscar had his hands about his throat choking him. I must have screamed. Oscar jumped up, and looked around. He said—he said just like himself,—‘What is it, mamma?’”

She stopped again and swallowed her tears.

“When I got down there, Ned was white and still. I thought he was dead. It was a long, long time before he got his breath, before he was himself. If, if I hadn’t wakened just then—”

Above them in the mottled sunshine on the lawn they could see little Oscar running, then stopping and listening, like some sprite escaped from the river alders. The man watched him springing over the turf, his little shirt fluttering in the breeze, and gradually his head sank. Then he straightened himself, and taking his wife’s hand led her back along the river path into the meadow.

“Ned Boyce is a bad-tempered little fellow: he irritated and exasperated Oscar until with the heat and all that he clutched him. We must think so at any rate. I’ll lick it out of him, if I catch him at it!” He ended with this feeble, masculine threat, this desire to take his exasperation out on somebody else—to be paid for his distress of mind. “But it frightens me to think of your coming here and thinking of doing such a thing!”

He turned his mood of reproach directly to her.

“If you had seen Ned lying there so white—it was whole minutes before he opened his eyes,”—she protested; and then it seemed to come over her in a wave that in her struggle with this evil she was alone,—her husband did not really understand what it meant. To him it was trouble, like difficulty with servants,—something which his buoyant nature refused to take altogether seriously. For him there was always a way out of a situation: to her there was no avenue out in this situation. She took her hand from his arm and stepped forth steadily by herself.

She had done him wrong! In his slower, less vivid mind, the tragedy was printing itself. He no longer could talk comfort. Something heavy and hard settled down on his spirit: he saw himself and this tender woman caught in a rocky bed of circumstance. In the gloom of his mind he could see no light, and he groaned.

Thus, together they mounted the slope of the lawn to the pleasant cottage, side by side and yet withdrawn from one another. As they reached the terrace little Oscar darted out, like a fleet arrow, from the big syringa where he had lain hidden. His voice rippled with joy:

“You’re so slow, you two! Do you see what I got? A piece of Mary’s Sunday cake. And that’s what’s left. I’ll give you that, mamma, if you’ll be good.”

“Take him away!” his mother exclaimed fretfully. “I can’t look at him yet. I have had enough for one day.”

She entered the house and locked herself in her room. Later, when her husband knocked, she opened the door; she had been sitting before her dressing-table, looking vacantly into the mirror.

“I don’t suppose you want to go over there to their party?” he ventured timidly. “I’ll send Tom over with a note.”

“Why would I not go? Why should I stay at home? Is this the sort of place a woman would want to stay in all the time, do you think? Heavens! if anything could make me forget for one quarter of an hour this idea,—anything, I would go—and sin for it too! Do you understand?”

The man’s face winced for the pain she had to bear. Again she burst out, looking into the mirror, her hair fallen about her strong young breast and shoulders:

“You brought this to me, you! Why didn’t something tell me of all that was hidden away in you, all that some day would come out from you and be mine? You did not let me know. Now I cannot get away from it! O my God! Why do you make me live? What right have you to make me live and endure?”

He did not resent her bitter reproaches. It was the instinctive recoil of her young body from terrible suffering, the first twitch of the flesh from the knife. There were no tears left in the eyes now; nothing shone there but passion and resentment.

“Stay at home? It’s the night of all others I’d go somewhere—get something. No! I won’t give in. I’ll get away from it, forget it, and be happy again. I will—see me do it.... They dine at half-past eight. Have the carriage at eight. I shall be ready.”

He walked to and fro in the dressing-room, wishing to say something that could soften her mood. At last he put his hand gently on her beautiful bare shoulders and lowered his face to hers.

“We must take this together, love,” he whispered simply.

“Don’t speak of it!” she cried, drawing herself from his touch. “Don’t touch me. I shall go mad, mad! You will have two instead of one, then.”