CHAPTER XXII

A NIGHT’S WORK

“Have is have, however men may catch.”

—SHAKESPEARE.

Under cover of the darkness Essex hurried down the street toward where the city passed from a place of homes to a business mart. He had at first no fixed idea of a goal, but after a few moments’ rapid march, realized that habit was taking him in the direction of Bertrand’s. An illumined clock face shining on him over the roofs told him it was some time past his dinner hour. He obeyed his instinct and bent his steps toward the restaurant, throwing the cloak over the fence of a vacant lot and wiping the trickle of blood from his cheek with his handkerchief.

He was cool and master of himself once more. His brain was cleared, as a sky by storm, and he knew that to-night’s interview must be one of the last he would have with the woman who had come to stand to him for love, wealth, success and happiness. He must win or lose all within the next few days.

Bertrand’s looked invitingly bright after the tempestuous blackness of the streets. Many of the white draped tables were unoccupied. His accustomed eye noted that the lady in the blue silk dress and black hat, and her companion with the bald head and cross-eye, who always sat at the right-hand corner table, were absent. He had fallen into the habit of bowing to them, and had more than once idly wondered what their relations were.

“Monsieur Esseex” to-night ate little and drank much. Etienne, the waiter, a black-haired, pink-cheeked garçon from Marseilles, noticed this and afterward remarked upon it to Madame Bertrand. To the few other habitués of the place, the thin-faced, handsome man with an ugly furrow down his cheek, and his hair tumbled on his forehead by the pressure of his hat, presented the same suavely imperturbable demeanor as usual. But Madame Bertrand, as a woman whose business it was to observe people and faces, noticed that monsieur was pale, and that when she spoke to him on the way in he had given a distrait answer, not the usual phrase of debonair, Gallic greeting she had grown to expect.

She looked at him from her cashier’s desk and reflected. As Etienne afterward repeated, he ate little and drank much. And how pale he looked, with the lamp on the wall above him throwing out the high lights on his face and deepening the shadows!

“He is in love,” thought the sentimental Madame Bertrand, “and to-night for the first time he knows that she does not respond.”

He sat longer than he had ever done before over his dinner, blowing clouds of cigarette smoke about his head, and watching the thin blue flame of the burning lump of sugar in the spoon balanced on his coffee-cup.

Everybody had left, and he still sat smoking, leaning back against the wall, his eyes fixed on space in immovable, concentrated thought. Bertrand came out of his corner, and in his cap and apron stood cooling himself in the open door watching the rain. Etienne and Henri, the two waiters apportioned to that part of the room, hung about restless and tired, eagerly watching for the first symptoms of his departure. Even Madame Bertrand began to burrow under the cashier’s desk for her rubbers, and to struggle into them with much creaking of corset bones and subdued French ejaculations. It was after nine when the last guest finally pushed back his chair. Etienne rushed to help him on with his coat, and Madame Bertrand bobbed up from her rubbers to give him a parting smile.

A half-hour later he was lighting the gas in his own room in Bush Street. The damp air of the night entered through a crack of opened window, introducing a breath of sweet, moist freshness into the smoke-saturated chamber. He threw off his coat and lit the fire. As soon as it had caught satisfactorily he left the room, crossed the hall noiselessly, and with a slight preliminary knock, opened Harney’s door. The man was sitting there in a broken rocking-chair, reading the evening paper by the light of a flaming gas-jet. He had the air of one who was waiting, and as Essex’s head was advanced round the edge of the door, he looked up with alert, expectant eyes.

“Come into my room,” said the younger man; “there’s work for you to-night.”

Harney threw down his paper and followed him across the hall. It was evident that he was sober, and beyond this some new sense of importance and power had taken from his manner its old deprecation. They were equals now, pals and partners. The drunken typesetter and one-time thief was still under Barry Essex’s thumb, but he was also deep in his confidence.

He sat down in his old seat by the fire, his eyes on Essex.

“What’s up?” he said; “what work have you got for me such a night as this?”

“Big work, and with big money behind it,” said the younger man; “and when it’s done we each get our share and go our ways, George Harney.”

He drew his chair to the other side of the fire and began to talk—his voice low and quiet at first, growing urgent and authoritative, as Harney shrank before the dangers of the work expected of him. The moments ticked by, the fire growing hotter and brighter, the roaring of the storm sounding above the voices of the master and his tool. The night was half spent before Harney was conquered and instructed.

Then the men, waiting for the hour of deepest sleep and darkness, continued to sit, occasionally speaking, the light of the leaping flames catching and losing their anxious faces as the firelight in another room was touching the face of the sleeping girl of whom they talked.

It was nearly three when a movement of life stirred the blackness of the Garcia garden. The rushing of the rain beat down all sound; in the moist soddenness of the earth no trace lingered. The pepper-tree bent and cracked to the gusts as it did to the additional weight of the creeping figure in its boughs.

This was merely a shapeless bulk of blackness amid the fine and broken blackness of the swaying foliage. It stole forward with noiseless caution, though it might have shouted and all sound been lost in the angry turmoil of the night. Creeping upward along the great limb that stretched to the balcony roof, a perpendicular knife-edge of light that gleamed from between the curtains of a window, now and then crossed its face, sometimes dividing it clearly in two, sometimes illuminating one attentive eye, a small shining point of life in the dead murk around it, one eye, aglow with purpose, gleaming startlingly from blackness.

The loud drumming of the rain on the balcony roof drowned the crackle of the tin under a feeling foot. To slide there from the limb only occupied a moment. The branch had grown well up over the roof, grating now and then against it when the wind was high. The thin streak of light from between the curtains made the man wary. Why was she burning a light at this hour unless she was sleepless and up?

Pressed close to the pane he applied his eye to the crack which was the widest near the sill. He saw a portion of the room, looking curiously vivid and distinct in the narrow concentration of his view. It seemed flooded with unsteady, warmly yellow light. Straight before him he saw a table with a rifled tea-tray on it, and back of that another table. The one eye pressed to the crack grew absorbed as it focused itself on the second table. Among a litter of books, ornaments and feminine trifles, stood a small desk of dark wood. It was as if it had been placed there to catch his attention—the goal of his line of vision.

Shifting his position he pressed his cheek against the glass and squinted in sidewise to where a deepening and quivering of the light spoke of a fire. Then he saw the figure of the sleeping woman, lying in an attitude of complete repose in the armchair. He gazed at her striving to gage the depth of her sleep. One of her hands hung over the arm of the chair, with the gleam of the fire flickering on the white skin. The same light touched a strand of loosened hair. Her face was in profile toward him, the chin pressed down on the shoulder. It looked like a picture in its suggestion of profound unconsciousness.

He pushed fearfully on the cross-bar of the pane, and the window rose a hair’s-breadth. Then again, and it was high enough up for him to insert his hand. He did so, and drew forward the curtain of heavy rep so as to hide from the sleeper the gradual stages of his entrance. By degrees he raised it to a height sufficient to permit the passage of his body. The curtain shielded the girl from the current of cold air that entered the room. He crept in softly on his hands and knees, then rose to his feet.

For a moment he made no further movement, but stood, his gaze riveted on the sleeper, watching for a symptom of roused consciousness. She slept on peacefully, the light sound of her breathing faintly audible.

The silence of the hushed house seemed weirdly terrifying after the tumult of the night outside. The thief stole forward to the desk, his eye continually turned toward her. When he reached the table she was so far behind him that he could only see the sweep of her wrapper on the floor, her shoulder, and the top of her head over the chair-back.

He tried the desk with an unsteady hand. It was locked, but the insertion of a steel file he carried broke the frail clasp. It gave with a sharp click and he stood, his hair stirring, watching the top of her head. It did not move, the silence resettled, he could again hear her light, even breathing.

There were many papers in the desk, bundles of letters, souvenirs of old days of affluence. He tossed them aside with tremulous quickness until, underneath all, he came on a long, dirty envelope and a little chamois leather bag. He lifted the latter. It was heavy and emitted a faint chink. The old thief’s instincts rose in him. But he first opened the envelope, and softly drew out the two certificates, took the one he wanted, and put the other back. Then he opened the mouth of the bag. The gleam of gold shone from the aperture. Stricken with temptation he stood hesitating.

At that moment the fire, a heap of red ruins, fell together with a small, clinking sound. It was no louder noise than he had made when opening the desk, but it contained some penetrating quality the former had lacked. Still hesitating, with the sack of money in his hand, he turned again to the chair. A face, white and wide-eyed, was staring at him round the side.

He gave a smothered oath and the sack dropped from his hand to the table. The money fell from it in a clattering heap and rolled about, in golden zigzags in every direction. The sound roused the still unawakened intelligence of the girl. She saw the paper in his hand, half-opened. Its familiarity broke through her dazed senses. She rose and rushed at him gasping:

“The certificate! the certificate!”

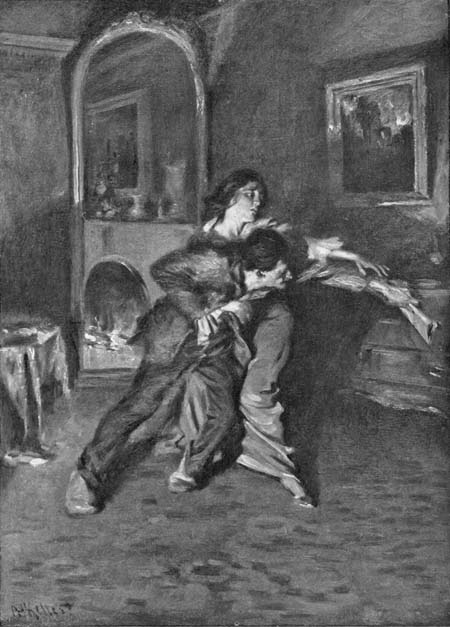

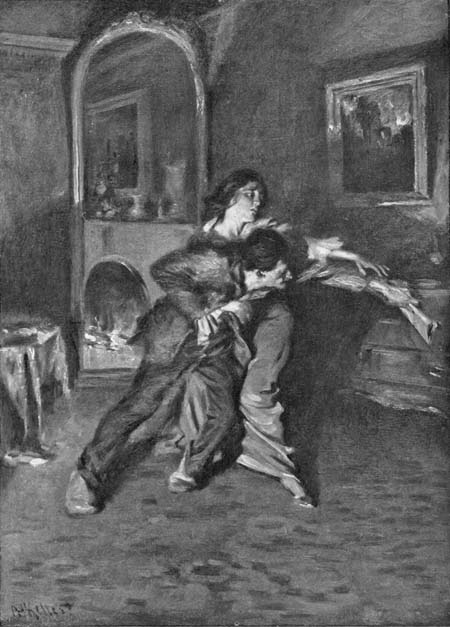

Harney made a dash for the open window, but she caught him by the shoulder and arm, and with the unimpaired strength of her healthy youth struggled with him hand to hand, reaching out for the paper he tried to keep out of her grasp. In the fury of the moment’s conflict, neither made any sound, but fought like two enraged animals, rocking to and fro, panting and clutching at each other.

He finally wrenched his arm free and struck her a savage blow, aimed at her head but falling on her shoulder, which sent her down on her knees and then back against the fire. He thought he had stunned her, and raised his arm again when she sprang up, tore the paper out of his grasp and pressed it with her hand down into the coals beside her. As she did so, for the first time she raised her voice and shrieked:

“Mr. Barron! Mr. Barron! Come, come! Oh hurry!”

From the hall Harney heard a movement and an answering shout. With the cries echoing through the room he beat her down against the grate, and tore the paper, curling with fire on the edges, from her hand. With it, he dashed through the open sash, a shiver of glass following him.

Almost simultaneously, Barron burst into the room. He had been reading and had fallen asleep to be waked by the shrieks of the girl’s voice, which were still in his ears. The falling of broken glass and a rush of cold air from the opened window greeted him. Piled on the table and scattered about the floor were gold pieces. Mariposa was kneeling on the rug.

“He’s got it!” she cried wildly, and struggling to her feet rushed to the window. “He’s got it! Oh go after him! Stop him!”

“Got what?” he said. “No, he hasn’t got the money. It’s all there.”

He seized her by the arm, for she seemed as if intending to go through the broken window.

“Not the money—not the money,” she shrieked, wringing her hands; “the paper—the certificate! He’s got it and gone, this way, through the window.”

Barron grasped the fact that she had been robbed of something other than the money, the loss of which seemed to render her half distracted. With a hasty word of reassurance, he turned and ran from the room, springing down the stairs and across the hall. In the instant’s pause by the window he had heard the sound of feet on the steps below and judged that he could get down more quickly by the stairs than by the limb of the tree.

But the few minutes’ start and the darkness of the night were on the side of the thief. The roar of the rain drowned his footsteps. Barron ran this way and that, but neither sight nor sound of his quarry was vouchsafed to him. The man had got away with his booty, whatever it was.

“WITH THE STRENGTH OF HER HEALTHY YOUTH SHE STRUGGLED WITH HIM”

In fifteen minutes Barron was back and found the Garcia ladies in Mariposa’s room, ministering to the girl who lay in a heavy swoon, stark and white on the hearth-rug.

The old lady, in some wondrous and intimate déshabille, greeted him eagerly in Spanish, demanding what had happened. He told her all he knew and knelt down beside the younger Mrs. Garcia, who was attempting with a shaking hand to pour brandy between Mariposa’s set teeth.

“We heard the most awful shrieks, and we rushed up, and here she was standing and screaming: ‘He’s got it! He’s got it!’ And then she fell flat, quite suddenly, and has lain here this way ever since.”

“It was a robber,” said the old woman, looking at the scattered gold, “but he didn’t get her money. What was it he took, I wonder?”

“Some papers, I think,” said Barron, “that were evidently of value to her. I’ll lift her up and put her on the bed and then I’ll go. As soon as she’s conscious ask her what the man took and come and tell me, and I’ll go right to the police station.”

“Oh, don’t leave us,” implored Mrs. Garcia, junior—“if there are burglars anywhere round. Oh, please don’t go. Pierpont’s away and we’d have no man in the house. Don’t go till morning. I’m just as scared as I can be!”

“There’s nothing to be scared about. The man’s got what he wanted, and he’ll take precious good care not to come back.”

“Oh, but don’t go till it gets light. The window’s broken and any one can come in who wants.”

“All right, I’ll wait till it gets light. I’ll lift her up now, if you’ll get the bed ready.”

With the assistance of old Mrs. Garcia he lifted her and carried her to the bed. One of her arms fell limp against his shoulder as he laid her down, and the old lady uttered an exclamation. She lifted it up and showed him a curious red welt on the white wrist.

“It’s a burn,” she said. “How did she get that?”

“She must have fallen against the grate,” he answered. His eyes grew dark as they encountered the scar. “As soon as she’s conscious tell me.”

A few minutes later, the young widow found him sitting on a chair under a lamp in the hall.

“Well,” he said eagerly, “how is she?”

“She’s come back to her senses all right. But she doesn’t seem to want to tell what he took. She says it was a paper, and that’s all, and that she never saw him before. Mother doesn’t think we ought to worry her. She says she’s got a fever, and she’s going to give her medicine to make her sleep, and not to disturb her till she wakes up. She’s all broken up and sort of limp and trembly.”

“Well, I suppose the señora knows best. It’ll be light soon now, and I’ll go to the police station. The señora and you will stay with her?”

“O yes,” said Mrs. Garcia, the younger. “My goodness, what a night it’s been! It’s lucky the man didn’t get her money. There was quite a lot; about five hundred dollars, I should think. Oh, my curl papers! I forget them. Gracious, what a sight I must look!” and she shuffled down the stairs.

Barron sat on till the dawn broke gray through the hall window. He was beginning to wonder if this girl was the central figure of some drama, secret, intricate and unsuspected, which was working out to its conclusion.