CHAPTER II

STRIKING A BARGAIN

“How the world is made for each of us!

How all we perceive and know in it

Tends to some moments’ product thus,

When a soul declares itself—to wit:

By its fruit, the thing it does!”

—BROWNING.

Where the foothills fold back upon one another in cool, blue shadows, and the tops of the Sierra, brushed with snow, look down on a rugged rampart of mountains falling away to a smiling plain, Dan Moreau and his partner had been working a stream bed since June. Placerville—still Hangtown—though already past the feverish days of its first youth, was some twenty-five miles to the southwest. A few miles to the south the emigrant trail from Carson crawled over the shoulder of the Sierra. Small trails broke from the parent one and trickled down from the summit, by “the line of least resistance,” to the outposts of civilization that were planted here and there on foothill and valley.

The cañon where Moreau and his “pard” were at work was California, virgin and unconquered. The forty-niners had passed it by in their eager rush for fortune. Yet the narrow gulch, that steamed at midday with heated airs and was steeped in the pungent fragrance which California exhales beneath the ardors of the sun, was yielding the two miners a good supply of gold. Their pits had honeycombed the stream’s banks far up and down. Now, in September, the water had dwindled to a silver thread, and they had dammed it near the rocker into a miniature lake, into which Fletcher—Moreau’s partner—plunged his dipper with untiring regularity, at the same time moving the rocker which filled the hot silence of the cañon with its lazy monotonous rattle.

They had been working with little cessation since early June. The richness of their claim and the prospect that the first snows would put an end to labors and profits had spurred them to unremitting exertion. In a box under Moreau’s bunk there were six small buckskin sacks of dust, joint profits of the summer’s toil.

Moreau, a muscular, fair-haired giant of a man, was that familiar figure of the early days—the gentleman miner. He was a New Englander of birth and education, who had come to California in the first rush, with a little fortune wherewith to make a great one. Luck had not been with him. This was his first taste of success. Five months before he had picked up a “pard” in Sacramento, and after the careless fashion of the time, when no one sought to inquire too closely into another’s antecedents, joined forces with him and spent a wandering spring, prospecting from bar to bar and camp to camp. The casual words of an Indian had directed them to the cañon where now the creak of their rocker filled the hot, drowsy days.

Of Harney Fletcher, Moreau knew nothing. He had met him in a lodging-house in Sacramento, and the partnership proved to be a successful one. What the New Englander furnished in money, the other made up in practical experience and general handiness. It was Fletcher who had constructed the rocker on an improved model of his own. His had been the directing brain as well as the assisting hand which had built the cabin of logs that surveyed the stream bed from a knoll above. The last remnants of Moreau’s fortune had stocked it well, and there were two good horses in the brush shed behind it.

It was now September, and the leaves of the aspens that grew along the stream bed were yellowing. But the air was warm and golden with sunshine. Above, in the high places of the Sierra, where the emigrant trail crept along the edges of ravines and crawled up the mighty flank of the wall that shuts the garden of California from the desert beyond, the snow was already deep. Fletcher, who had gone into Hangtown the week before for provisions, had come back full of stories of the swarms of emigrants pouring down the main road and its branching trails, higgledy-piggledy, pell-mell, hungry, gaunt, half clad, in their wild rush to enter the land of promise.

There was no suggestion of winter here. The hot air was steeped in the aromatic scents that the sun draws from the mighty pines which clothe the foothills. At midday the little gulley where the men worked was heavy with them. All about them was strangely silent. The pines rising rank on rank stirred to no passing breezes. There was no bird note, and the stream had shrunk so that its spring-time song had become a whisper. Heat and silence held the long days, when the red dust lay motionless on the trail above, and the noise made by the rocker sounded strangely intrusive and loud in the enchanted stillness that held the landscape.

On an afternoon like this the men were working in the stream bed—Moreau in the pit, Fletcher at his place by the rocker. There was no conversation between them. The picture-like dumbness of their surroundings seemed to have communicated itself to them. Far above, glittering against the blue, the white peaks of the Sierra looked down on them from remote, aërial heights. The tiny thread of water gleamed in its wide, unoccupied bed. Save the men, the only moving thing in sight was a hawk that hung poised in the sky above, its winged shadow floating forward and pausing on the slopes of the gulch.

Into this spellbound silence a sound suddenly broke—a sound unexpected and unwished for—that of a human voice. It was a man’s, harsh and loud, evidently addressing cattle. With it came the creak of wheels. The two partners listened, amazed and irresolute. The trail that passed their cabin was an almost unknown offshoot from the main highway. Then, the sounds growing clearer, they scrambled up the bank. Coming down the road they saw the curved top of a prairie schooner that formed a background for the forms of two skeleton horses, beside which walked a man who urged them on with shouts and blows. Wagon and horses were enveloped in a cloud of red dust.

At the moment that the miners saw this unwelcome sight, one of the wretched beasts stumbled, and pitching forward, fell with what sounded like a human groan. The man, with an oath, went to it and gave it a kick. But it was too far spent to rally, and settling on its side, lay gasping. A woman, stout and sunburned, ran round from the back of the cart, with a face of angry consternation. As Moreau approached, he heard her say to the man who, with oaths and blows, was attempting to drag the horse to its feet:

“Oh, it ain’t no use doing that. Don’t you see it’s dying?”

Moreau saw that she was right. The animal was in its death throes. As he came up he said, without preliminaries:

“Take off its harness, the poor brute’s done for,” and began to unbuckle the rags of harness which held it to the wagon.

The man and woman turned, startled, and saw him. Looking back they saw Fletcher, who was coming slowly, and evidently not very willingly, forward. The sight of the exhausted pioneers was a too familiar one to interest him. The dying horse claimed a lazy cast of his indifferent eye. Moreau and the man loosed the harness, lifted the pole, and let the creature lie free from encumbrance. The other horse, freed, too, stood drooping, too spent to move from where it had stopped. If other testimony were needed of the terrible journey they were ending, one saw it in the gaunt face of the man, scorched by sun, seamed with lines, with a fringe of ragged beard, and long locks of unkempt hair hanging from beneath his miserable hat.

This stoppage of his journey with the promised land in sight seemed to exasperate him to a point where he evidently feared to speak. With eyes full of savage despair he stood looking at the horse. Both he and the woman seemed so overpowered by the calamity that they had no attention to give to the two strangers, but stood side by side, staring morosely at the animal.

“What’ll we do?” she said hopelessly. “Spotty,” indicating the other horse, “ain’t no use alone.”

Moreau spoke up encouragingly.

“Why don’t you leave the wagon and the other horse here? You can walk into Hangtown by easy stages. The Porter ranch is only twelve miles from here and you can stay there all night. The poor beast can’t do much more, and we’ll feed it and take care of your other things while you’re gone.”

“Oh, damn it, we can’t!” said the man furiously.

As if in explanation of this remark, a woman suddenly appeared at the open front of the wagon. She had evidently been lying within it, and had not risen until now.

When Moreau looked at her he experienced a violent thrill of pity, that the evident sufferings of the others had not evoked. He was a man of a deeply tender and sympathetic nature toward all that was helpless and weak. As his glance met the face of this woman, he thought she was the most piteous object he had ever seen.

“You’d better come into the cabin,” he said, “and see what you can do. You can’t go on now, and you look pretty well used up.”

The man gave a grunt of assent, and taking the other horse by the head began to lead it toward the cabin, being noticeably careful to steer it out of the way of all stumbling-blocks. The woman in the sunbonnet called to her companion in the wagon:

“Come, Lucy, get a move on! We’re going to stop and rest.”

Thus addressed, the woman moved to the back of the cart, drew the flap aside and slipped out. She came behind the others, and Moreau, looking back, saw that she walked slowly, as if feeble, or in pain.

Advancing to the sunbonneted figure in front of him he said, with a backward jerk of his head: “What’s the matter with her? Is she sick?”

The woman gave an indifferent glance backward. Like the man, she seemed completely preoccupied by their disaster.

“Not now,” she answered, “but she has been. But good Lord!”—with a sudden burst of angry bitterness—“women like her ain’t meant to take them sort of journeys. If it weren’t for her, Jake and I could go on all right.”

She relapsed into silence as the cabin revealed itself through the trees. It appeared to interest her, and she went to the door and looked in.

It was the typical miner’s cabin of the period, consisting of a single room with two bunks. Opposite the doorway was the wide-mouthed chimney, a slab of rock before it doing duty as hearthstone. There was an armchair formed of a barrel, cushioned with red flannel and mounted on rockers. Moreau’s bunk was covered with a miner’s blanket, and the ineradicable habits of the gentleman spoke in the very simple but sufficient toilet accessories that stood on a shelf under a tiny square of looking-glass. Over the roof a great pine spread its boughs, and in passing through these the slightest breaths of air made soft eolian murmurings. To the pioneers, the wild, rough place looked the ideal of comfort and luxury.

A small spring bubbled up near the roots of the pine and trickled across the space in front of the cabin. To this, by common consent, the party made its way. The exhausted horse plunged its nose in the cool current and drank and snorted and drank again. The elder woman knelt down and laved her face and neck and even the top of her head in the water. The man stood looking with a moody eye at his broken animal, and joined by Fletcher, they talked over its condition. The miner, versed in this as in all practical matters, deemed the beast incapacitated for journeys of any length for some time to come. Both animals had been driven to the limit of their strength.

The pioneer asserted:

“I had to get acrost before the snows blocked us, and they’re heavy up there now,” with a nod of his head toward the mountains above; “then I wanted to get down into the settlements as soon’s I could. I knew there weren’t two more days work in ’em, but I calk’lated they’d get me in. After that it didn’t matter.”

“The only thing for you to do is to walk into Hangtown, buy a mule there, and come back.”

The man made a despairing gesture.

“How the hell can I, with her?” he said, indicating the younger woman.

Fletcher turned round and surveyed her with a cold, exploring eye where she had sunk down on the roots of the pine, with her back against its trunk.

“She looks pretty well tuckered out,” he said. “Your wife?”

“Yes.”

“And the other one’s your sister?” he continued with glib curiosity.

“She’s my wife, too.”

The inquirer, who was used to such plurality on the part of the Utah emigrants, gave a whistle and said:

“Mormons, eh?”

The man nodded.

Meantime Moreau had entered the cabin to get some food and drink to offer the sick woman. In a few moments he reappeared carrying a tin cup containing whisky diluted with water from the spring, and approached the woman sitting by the tree trunk. Her eyes were closed and she presented a deathlike appearance. The shawl she had worn round her shoulders had fallen back and disclosed a small bundle that she held with a loose carefulness. The man noticed the way her arms were disposed about it and wondered. Coming to a standstill before her, he said:

“I’ve brought you something that’ll brace you up. Would you like to try it?”

She raised her lids and looked at him, and then at the cup. As he met her glance he noticed that her eyes were a clear brown like a dog’s, and for the first time he realized that she might be young. She stretched out her hand obediently and taking the cup drank a little, then silently gave it back.

“You’ve had a pretty rough time I guess,” he said, holding the cup which he intended to give her again in a minute.

She nodded. Then suddenly the tears began to well out of her eyes, quantities of tears that ran in a flood over her cheeks. She did not sob or attempt to hide her face, but leaning her head against the tree, let the tears flow as though lost to everything but her sense of misery.

“Oh, poor thing! poor thing!” he exclaimed in a burst of sympathy, “you’re half dead. Here take some more of this,” and he pressed the cup into her hand, not knowing what else to do for her.

She took it, and then, through the tears, he saw her cast a look of furtive alarm toward her husband. She was within his line of vision and tried to shift herself behind Moreau.

With a sensation of angry disgust he understood that she feared this unkempt and haggard creature to whom she belonged. He moved so that he sheltered her and watched her try to drink again. But her tears blinded her and she handed the cup back with a shaking hand.

“It’s been too much,” she gasped. “If I could only have died! My boy did. Out there on them awful plains where there ain’t a tree and it’s hot like a furnace. And they buried him there—Bessie and he.”

“Bessie and he?” he repeated vaguely, his pity entirely preoccupying his mind for the moment.

“Yes, Bessie,—the second wife. I’m the first.”

“Oh,” he said, comprehending, “you’re from Utah?”

“Not me,” she answered quickly, “I’m from Indiana. I’m no Mormon. He wasn’t neither till he married Bessie. He wanted her and he did it.”

Here she was suddenly interrupted by a weak whining cry from the bundle that one arm still curved about. She bent her head and drew back the covering, and Moreau saw a strange wizened face and a tiny, claw-like hand feeling feebly about. He had never seen a very young infant before and it seemed to him a weirdly hideous thing.

“Is it yours?” he said, amazed.

“Yes,” she answered, “it was born in the desert three weeks ago.”

Her tears were dry, and she bent over the feeble thing that squirmed weakly and made small, cat-like noises, with something in her attitude that changed her and made her still a woman who had a life above her miseries.

“Wouldn’t you like to go into the cabin?” said the man, feeling suddenly abashed by his ignorance of all pertaining to this infinitesimal bit of life. “You might want to wash it or put it to sleep or give it something to eat. There’s a basin and soap and—er—some flour and bacon in there.”

The woman responded to the invitation with a slight show of alacrity. She stumbled as she rose, and he took her arm and guided her. At the cabin door he left her and as he passed to the back where the rest of the party had gone, the baby’s feeble cry, weak, but insistent, followed him.

The emigrant, Bessie and Fletcher, had repaired to the brush shed where Moreau’s horses were stabled and had put the half-dead Spotty under its shelter. Here the exhausted beast had lain down. The trio had then betaken themselves to a bare spot on the shaded slope of the knoll and were eating ship’s biscuits and drinking whisky and water from a tin cup, that circulated from hand to hand. As Moreau approached he could hear his partner volubly expatiating on the barrenness of the stream-beds in the vicinity. The stranger was listening to him with a cogitating eye, his seamed, weather-worn face set in an expression of frowning attention. Her hunger appeased, Bessie had curled up on her side, and with her sunbonnet still on, had fallen into a deep, healthy sleep.

Moreau joined them, and listened with mingled surprise and amusement to Fletcher’s glib lies. Then, when his partner’s fluency was exhausted, he questioned the emigrant on his trip. The man’s answers were short and non-committal. He seemed in a morose, savage state at his ill luck, his mind still engrossed by the question of moving on.

“If I’d money,” he said, “I’d give you anything you’d ask for them two horses ’er your’n in the shed. But I ain’t a thing to give—not a red.”

“Your wife, your other wife,” said Moreau, “doesn’t seem to me fit to go on. She’s dead beat.”

The man gave an angry snort.

“She’s been like that pretty near the whole way,” he said. “Everything’s been put back because of her.”

He relapsed into moody silence and then said suddenly: “We’re goin’ if she’s got to walk.”

Moreau went back to the cabin. They had half killed the woman already; now if they insisted on her walking the wretched creature might collapse altogether. Would they leave her on the mountain roads, he wondered?

He reached the cabin door, knocked and heard her answering “come in.” She was sitting on an upturned box beside the bunk on which the baby slept. Her sunbonnet was off, and he noticed that she had bright hair, rippled and thick, and of the same reddish-brown color as her eyes. She had washed away the traces of her tears, but her clothes, hardly sufficient covering for her lean, toil-worn body, were dirty and ragged. No beggar he had ever seen in the distant New England town where he had spent his boyhood, had presented a more miserable appearance. She looked timidly at him and rose from the box, pushing it toward him.

“I put the baby on the bunk,” she said apologetically, “but I can hold her.”

“Oh, don’t disturb her,” he said quickly. “It’s the only place you could have put her.” Then, seeing her standing, he said, “Why don’t you sit down?”

She sat charily and evidently ill at ease.

“They’ve been eating out there,” he said, “and I thought you might like something, too. There’s some stuff over there in the corner if you’ll wait a moment.”

He went to the corner where the supplies were stored and rifled them for more ship’s biscuit and a wedge of cheese, a delicacy which Fletcher had brought from Hangtown on his last visit, and which he carefully refrained from offering to the hungry emigrants. Coming back with these he drew out another box and spread them on it before her. She looked on in heavy, silent surprise. When he had finished he said:

“Now—fall to. You want food as much as anything.”

She made no effort to eat, and he said, disappointed: “Don’t you want it? Oh, make a try.”

She “made a try,” and bit off a piece of cracker, while he again retired to the supply corner for the tin cup and the whisky. He tried to step softly so as not to wake the child, and there was something ludicrous in the sight of this vast, bearded man, with his mighty, half-bared arms and muscular throat, trying to be noiseless, with as much success as one might expect of a bear.

Suddenly, in the midst of her repast, the woman broke down completely; and, with bowed head, she was shaken by a tempest of some violent emotion. It was not like her tears of an hour before, which seemed merely an indication of physical exhaustion. This was an expression of spiritual tumult. Sobs rent her and she rocked back and forth struggling with some fierce paroxysm.

Moreau, cup in hand, gazed at her in distracted helplessness.

“Come now, eat a little,” he said coaxingly, not knowing what else to suggest, and then getting no response: “Suppose you lie down on the bunk? Rest is what you want.”

“Oh, I can’t go on,” she groaned. “I can’t. How can I? Oh, it’s too much! I can’t go on.”

He was silent before this ill for which he had no remedy, and she wailed again in the agony of her spirit:

“I can’t, I can’t. If I could only die! But now there’s the baby, and I can’t even die.”

He got up feeling sick at heart at sight of this hopeless despair. What could he suggest to the unfortunate creature? He felt that anything he could say would be an insult in the face of such a position.

“Oh God, why can’t we die?” she groaned—“why can’t we die?”

As she said the words the sound of approaching voices came through the open door. Her husband’s struck through her agony and froze it. She stiffened and lifted her face full of an animal look of listening. Moreau noticed her blunt and knotted hands, pitiful in their record of toil, as she held them up in the transfixed attitude of strained attention.

“What now?” she said to herself.

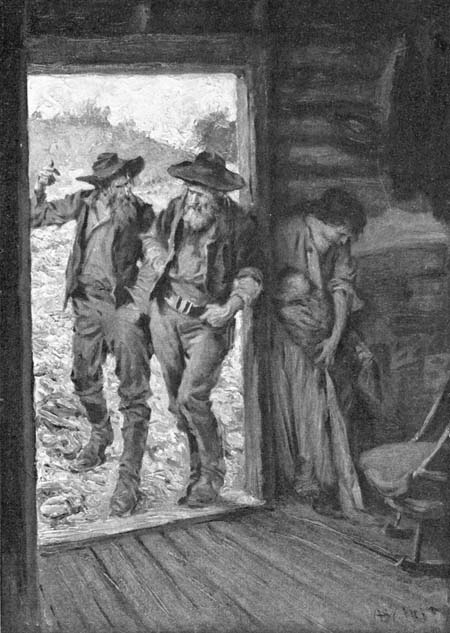

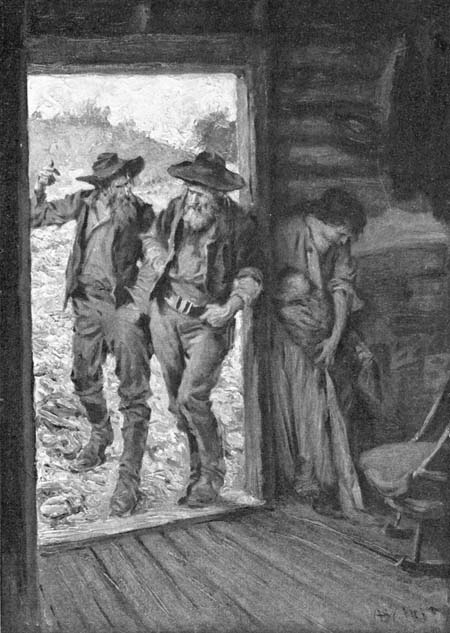

The pioneer, Fletcher and Bessie came slowly round the corner of the cabin. Bessie looked sleepily anxious, Fletcher lazily amused. As Moreau stepped out of the doorway toward them he realized that they had come to some decision.

“Well,” said the man, “we got to travel.”

“You’re going on?” said Moreau. “How about the wagon?”

“We’re goin’ to leave the wagon, and I’ll come back for it from Hangtown. It’s the only thing to do.”

“And the horse?”

“He calk’lates,” said Fletcher, “to mount his wife—the peaked one—on the horse and take her along till one or other of ’em drops.”

“Take your wife on that horse?” exclaimed Moreau. “Why, it can’t go two miles.”

“Well, maybe it can’t,” returned the man with an immovable face.

There was a pause. Moreau was conscious that the woman was standing behind him in the doorway. He could hear her breathing.

“Come on, Lucy,” said the husband. “We got to move on sometime.”

Here the second wife spoke up:

“I don’t see how the horse is goin’ to get Lucy twelve miles, and this man says the first place we can stop is twelve miles farther along.”

“Don’t you begin with your everlasting objections,” said the husband, furiously. “Get the horse.”

The woman evidently knew the time had passed for trifling and turned away toward the brush shed. Fletcher followed her with a grin. The situation appealed to his sense of humor, and he was curious as to the outcome.

Moreau and the emigrant were left facing each other, with the first wife in the doorway.

“Your wife’s not able to go on,” said the miner—his manner becoming suddenly authoritative; “no more than your horse is.”

“Maybe not,” said the other, “but they’re both goin’ to try.”

“But can’t you see the horse can’t carry her? She certainly can’t walk into Hangtown, or even to Porter’s Ranch.”

“No, I can’t see. And how’s it come to be your business—what they can do or what they can’t?”

“YOUR WIFE’S NOT ABLE TO GO ON, NO MORE THAN YOUR

HORSE IS”

“It’s any one’s business to prevent a woman from being half killed.”

“Since you seem to think so much about her, why don’t you keep her here yourself?”

The man spoke with a savage sneer, his eyes full of steely defiance.

Before he had realized the full import of his words, burning with rage against the brutal tyrant to whom the wife was of no more moment than the horse, Moreau answered:

“I will—let her stay!”

There was a moment’s pause. The emigrant’s face, dark with rage, was suddenly lightened by a curiously alert expression of intelligence. He looked at the woman in the background and then at the miner.

“I’m not giving anything away just now,” he answered. “When she’s well she’s of use. But I’ll swap her for your two horses.”

In the heat of his indignation and disgust Moreau turned and looked at the woman. She was leaning against the door frame, chalk-white, and staring at him. She made no sound, but her dog-like eyes seemed to speak for his mercy more eloquently than her tongue ever could.

“All right,” he said quietly. “It’s a bargain.”

“Done,” said the emigrant. “You’ll find her a good worker when she pulls herself together. You stay on here, Lucy. Bessie,” he sang out, “bring around them horses.”

Under the phlegm of his manner there was a sudden expanding heat of shame that he strove to hide. The woman neither stirred nor spoke, and Moreau stood with his back to her, struggling with his passion against the man who had been her owner. The impulse under which he had spoken had full possession of him, and his main feeling was his desire to rid himself of the emigrant and his other wife.

“Here,” he said, “go on and tell them that you’ll take the horses. Hurry up!”

The man needed no second bidding and made off rapidly round the corner of the cabin.

Moreau and the woman were silent. For the moment he had forgotten her presence, engrossed by the rage that filled his warmly generous nature. Instinctively he followed the man to the angle of the cabin whence he could command the brush shed. The trio were standing there, Fletcher and the woman listening amazed to the emigrant’s explanation. Moreau turned back to the cabin and his eye fell on the woman in the doorway.

“Well,” he said—trying to speak easily—“you don’t mind staying on here for a while, do you? I guess we can make you comfortable.”

She made no answer, and after waiting a moment he said:

“When you get stronger I’ll be able to find you something to do in Hangtown. You know you couldn’t go on, feeling so bad. And this air round here”—with a wave of his hand to the surrounding pines—“will brace you up finely.”

She gave a murmured sound of assent, but more than this made no reply. Only her dog-like eyes again seemed to speak. Their miserable look of gratitude made Moreau uncomfortable and he could think of nothing more to say.

The sound of the trio advancing from the shed came as a welcome interruption. They appeared round the corner of the cabin, leading the miner’s two powerful and well-fed horses. Evidently the situation had been explained. Fletcher’s face was enigmatical. The humorousness of the novel exchange had come a little too close to his own comfort to be quite as full of zest as it had been earlier in the afternoon. He had insisted that the emigrant leave his horse, which the man had no objection to doing. Bessie looked flushed and excited. Moreau thought he detected shame and disapproval under her agitated demeanor. But to her work was a matter of second nature. She put the horses to the tongue of the wagon and buckled the rags of harness together before she turned for a last word to her companion. This was characteristically brief:

“So long, Lucy,” she said, “let’s see the baby again.”

It was shown her and she kissed it on the forehead with some tenderness. Then she climbed on the wheel of the wagon and took from the interior a bundle tied up in printed calico and laid it on the ground. It contained all the personal belongings and wardrobe of the first wife. There were a few murmured sentences between them and then she turned to ascend to her seat. But before she had fairly mounted a sudden impulse seized her and whirled her back to give Lucy a good-by kiss.

There was more feeling in this action than in anything that had passed between the trio during the afternoon. The two wives had been women who had mutually suffered. There were tears in Bessie’s eyes as she climbed to her place. The husband never turned his head in the direction of his first wife. But as he took the reins and prepared to start the team, he called:

“Good by, Lucy.”

He clucked at the horses, and the wagon moved forward amid a stir of red dust. The woman on the front seat drew her sunbonnet over her face. The man beside her looked neither to the right nor the left, but stared out over his newly-acquired team with an impassively set visage. His long whip curled out with a hiss, the spirited animals gave a forward bound, and the wagon went clattering and jolting down the trail.

Moreau stood watching its canvas arch go swinging downward under the dark boughs of the pines and the flickering foliage of the aspens. He watched until a bend in the road hid it. Then he turned toward the cabin. Fletcher was standing behind him, surveying him with a cold and sardonic eye:

“Well, you’ve done it!”

“I guess I have.”

“What the devil are you going to do with her?”

“Don’t know.”

“And the horses gone; nothin’ but that busted cayuse left!”

They stood looking at each other, Fletcher angrily incredulous, Moreau smilingly deprecating and apologetic.

As they stood thus, neither knowing what to say, the emigrant’s wife appeared at the doorway of the cabin.

“I’ll get your supper now if it’s the right time,” she said timidly.