CHAPTER XXXI—WINONA, THE INDIAN MAIDEN.

Luckily for Tom’s comfort, the storm which had threatened when he left V. M. Ranch was turned by a changing wind toward the south; and, when the chill grey of daylight came, he found that he had ridden many miles to the north and that he was slowly crossing a vast, wild broken upland, which was gradually ascending toward a range of mountains that looked grim, lonely and forbidding.

In those barren walls of rock, Virginia had told him that he would find the almost hidden entrance to the Papago Indian village.

No creature was in sight at that early hour save a low sailing hawk, and, now and then, a lizard, frightened by the horse’s hoofs, darted across the trail. So near was it to the color of the sand that only by its quick flashing motion could it be discerned.

As Tom neared the seemingly impenetrable wall of rock, it was hard for him to believe that this was really a fortress surrounding a village of any kind. He was weary and hungry, but, try as he might, he could not find the entrance.

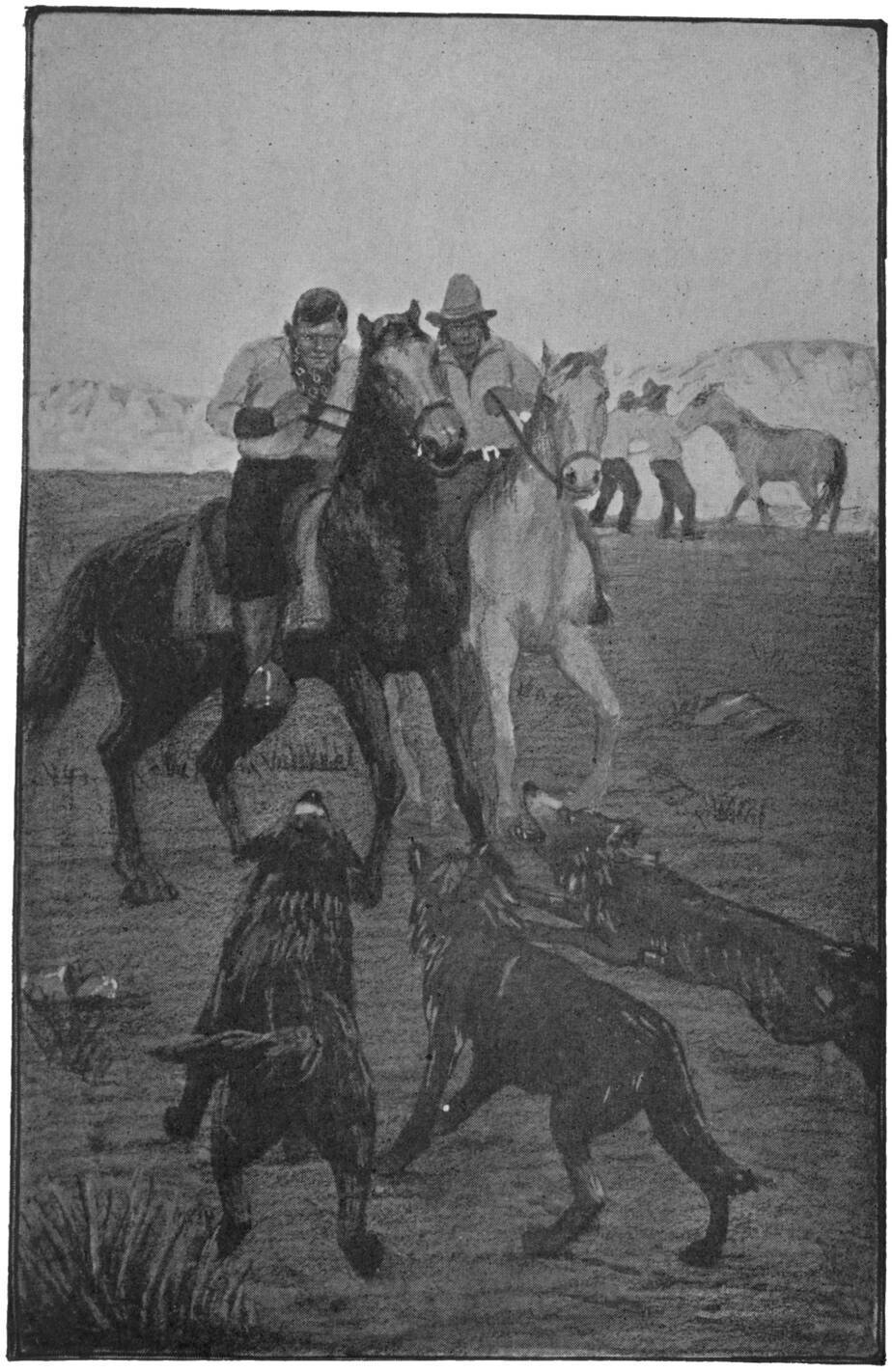

When the two riders appeared a pack of wolf-dogs made a mad rush at the stranger.

Suddenly his horse snorted and stopped. Tom wondered what it had heard for surely there was nothing to see, but he was not long puzzled, for a second later a lean, shaggy pony, ridden by a small Indian boy, emerged from what seemed to be solid rock. Tom urged his horse forward and hailed the little fellow who, after looking at the stranger with startled eyes, seemed about to return by the way he had come. Then it was Tom remembered something. He had been told to say to the first Indian he met, “Virginia Davis sent me,” which sentence, he had been assured would prove an open sesame that would win for him admittance and welcome.

Nor had he been misinformed, for, when the small Indian boy who was about to disappear, heard the name which Tom called, he smiled, showing two rows of gleaming white teeth, and then, silently beckoning he led the way through a crevice, so narrow that Tom no longer wondered that it had escaped his observation.

It gradually widened, however, into a canyon which at last opened into a huge bowl-shaped valley where the grass was green and where clumps of scarlet flowers were blossoming.

Scattering about were a dozen or more low adobe huts and in the midst of them in a large corral were many wiry Indian ponies.

When the two riders appeared a pack of wolf-dogs made a mad rush at the stranger, barking furiously. However at a word of command from the small Indian boy, they slunk away, to Tom’s secret relief. The lad had evidently assured them that the intruder was a friend and not a foe.

The Indian boy knew little English, but he led Tom to the most imposing of the adobe huts. There he paused and uttered a cry like that of some wild bird.

Tom gazed curiously at the open door which was festooned with dried red peppers. He wondered who would appear. He hoped and believed that it would be Winona, the Indian maiden, who was Virginia’s friend, but instead a shriveled old Indian woman wrapped in a bright-colored blanket shuffled to the door and evidently asked the lad what he wished at the home of the chief.

Tom understood only one word in the lad’s reply and that was “Winona.” For answer the old woman silently pointed toward the nearest cliff. Tom, looking in that direction, saw a graceful Indian girl approaching and on her head she was balancing a very large red pottery jar which was almost brimming full of sparkling water from a mountain spring.

Whirling his pony, the little Indian had galloped toward the dusky maiden, who paused to listen to what he had to say with an eager interest.

Then, placing her water jar upon a large, flat rock, she approached the newcomer who had dismounted, having first assured himself that the pack of wolf-like dogs was not in evidence.

To his surprise the Indian maiden spoke in the English language and, without the least embarrassment held out her slim, dark hand as she said, “Welcome, Virginia’s friend. You have traveled far and are hungry. I am Winona and I will give you breakfast.”

Tom thanked her and, as she was about to lift the jar again to her head, he said with his frank, friendly smile, “I ought to offer to carry that, but I fear I could not manage it as skillfully as you do. Since it is without handles, it must be a difficult feat.”

Winona smiled up at him as they walked side by side; the Indian lad, whose name was Red Feather, having taken Tom’s horse to the corral.

“Perhaps,” she replied, “but we learn early and do not forget. Look yonder.”

Tom’s glance followed that of Winona and he saw a group of little Indian girls, the oldest not more than 10. They were coming from a mountain spring and each was balancing a water jar upon her head. The small girls gathered about gazing half shyly and half curiously at the newcomer, until Winona spoke a few words in a tone of gentle rebuke, then the little, wild, coyote-like creatures scattered and soon disappeared in different mud huts.

“What did you say to them, Winona?” Tom asked curiously.

The Indian girl’s smile was almost merry. “That it isn’t manners to stare at company,” was the reply. “For seven winters, as Virginia told you, I learned the white man’s way, and now I have a little class and teach what I learned. Here we are at my home. My father awaits to welcome you.”

Tom saw an old Indian squatted upon the mud porch, and about his jet-black hair was a band into which had been woven with garnet beads the emblem of the tribe.

“My father, Chief Grey Hawk, this is Tom, friend of Virginia.” The bronzed, wrinkled face had a kindly expression as the old man replied in his own tongue, offering hospitality.

“Sit and rest and I will bring refreshment,” Winona said as she went within, soon to return with steaming coffee and a hard cake made from Indian meal.

The chief having retired, Winona sat beside Tom on the adobe porch and asked many questions about Virginia.

An hour later Tom bade the Indian girl farewell, and with little Red Feather as guide, he again rode toward the north. As he looked ahead at the rugged, uninviting mountains, in his heart there was an impulse to whirl his horse about and gallop back to the V. M. Ranch, whatever the consequences, but instead he followed the lad who led the way across an ever rising sandy waste where there was no sign of a trail. Had there been one the frequent whirlwinds would have hidden it with sand.

Tom wondered if the Indian boy had the same unerring instinct that a bird seems to have in its flight. Once only did the small guide pause and listen. Tom, too, drew rein, but heard nothing, although it was evident that the Indian lad did. He was intently watching a sandhill nearby, around which, in another moment, there appeared a bunch of wild, shaggy ponies, but, upon seeing Tom and Red Feather, with a shrill whistle-like neighing, they whirled about and galloped in the other direction and were soon hidden in a cloud of sand.

The Indian lad looked back and his white teeth gleamed as he said, “Much pony-wild.”

That was his first attempt at speaking the English language and would have surprised Tom greatly had he not recalled that Red Feather was probably a pupil in Winona’s little class, and so, riding closer, he asked, “Is it far yet we go? Long way?”

The lad shook his head. He had understood. “One up, one down,” was his curious reply. Tom decided that the little fellow meant that they would cross one more range of mountains and then descend into a valley, nor was he wrong, for they were soon climbing a clearly defined mountain trail and at last reached a high point from which Tom could see, far below them, a wide, fertile valley.

Red Feather drew rein and pointed. “Sheep,” he said. “I go back.” Not waiting for Tom to express his gratitude, and without a formal farewell, the Indian lad returned by the way he had come.

Tom, believing that the sheep ranch he sought lay in the valley below, started the descent.

As he neared the group of low, white-washed buildings, Tom felt in his heart a strange loneliness and a sense of homesickness for the V. M. Ranch.

After years of wandering, the few days he had spent there had meant so much to him, but it had been Virginia’s wish that he seek refuge on this sheep ranch, and so he rode on, wondering what manner of welcome he would receive.

Mr. Wilson and his 18-year-old son, Harry, were mounted and apparently about to ride away from the big white-washed ranch house when they perceived the newcomer and drew rein to await him. They wondered who the visitor might be, as few riders passed that way, the sheep ranch being isolated and difficult of access.

When the lad was within hailing distance, Mr. Wilson, in his bluff, hearty manner, called:

“Welcome, stranger!”

Tom responded to the greeting and said:

“Mr. Wilson, I am from the V. M. Ranch. An old cattleman, whom they call ‘Uncle Tex,’ brought word that you were in need of help and I have come to apply for a position.”

“Good! We do indeed need help,” was the hearty response. “Have you any knowledge of sheep?”

“None whatever,” was the frank reply, “and before I accept a position with you, I would like to tell you just who I am.”

“That is not at all necessary,” Mr. Wilson replied, heartily. “Your honest face and manner are all the recommendations that you need. Your past, my boy, is past. Your present will be what you make it now.” Then he added, “This is my son, Harry. What shall we call you?”

“Tom,” was the simple reply.

“Tom,” Mr. Wilson repeated, “you have come at a very opportune time. Harry and I were just setting out for the Red Canyon camp. Our herder there, Juan, reports that many sheep are being killed in his flock, but that alone he cannot watch them at all hours. Of course he must have sleep, and although I am really needed on the home ranch, I am so short of help that I was about to accompany Harry. Will you go in my place?”

“Gladly, sir,” Tom replied.

“Then first come within and have refreshments and meet the Little Mother who makes home for us.”

Mrs. Wilson welcomed the lad with the same kindliness that her husband extended to him and led him at once to the big, comfortable kitchen where he was soon given a bountiful dinner, which he greatly appreciated.

An hour later, with Harry and on a fresh mount, Tom started again toward the north. The boys liked each other at once. Tom was soon asking many questions about sheep ranching, which the other lad seemed glad to answer.

Then, for a time, they rode on silently. Tom was thinking how pleased Virginia would be if she could know of the kindly welcome he had received. How he wished that he could write to her.

“Can one send a letter from here to the V. M. Ranch?” he inquired.

“Yes,” Harry replied; “about once a month we send our mail to Red River Junction, which is thirty miles away. Little Francisco will go to town in about a week.”