CHAPTER IX.

THE MIDNIGHT ATTACK.

WHISTLER’S wounded finger continued to heal rapidly, and it now occasioned him but little trouble. He did not use his left hand much, however; and one day he was a good deal surprised, and a trifle alarmed, on discovering that the arm itself had become much smaller than the other. He at once showed it to his aunt, who relieved his apprehensions by assuring him that its shrunken appearance was owing to its not being used. She also improved the opportunity to give him a few hints on the importance of exercise to bodily health.

“If you should keep your arm motionless for a long time,” she said, “it would finally wither and become useless. So it is with our whole bodies,—they suffer, and fall away, if they do not get exercised enough. The reason that Clinton is stronger and stouter than you is, that his body has been exercised more than yours. He was quite slender when he was a little child. And it is precisely the same with our minds. If we want to increase any of our faculties, we must make a good use of them, and they will be sure to grow. But, if we don’t exercise them, they will fall away, just as your arm has done.”

One morning, a few days after the picnic, there was a great commotion on the premises, occasioned by the discovery that some murderous marauder had visited the yard in the night, and taken the lives of a score of Clinton’s hens and chickens. A brood of young chickens, which slept in a barrel laid upon its side, apart from the other fowls, were all murdered, together with their mother; while in the hen-house the ground under the roosts was strewn with the bodies of the slaughtered. Clinton rushed into the house in a high state of excitement, on making the discovery, and the whole family hastened to see the bloody spectacle. Many were the exclamations of sorrow and pity, as they gazed upon the bodies of plump, matronly hens, and exemplary pullets, and feeble, infantile chickens, now stiffened in death, their plumage ruffled and stained with blood. Several of the fowls, however, were missing, having evidently been either devoured or carried off. Among these was one of the lords of the poultry-yard, who, perhaps, had attempted to defend his family from the midnight assassin, and had been carried off bodily, as a trophy of victory. The survivors were silent and melancholy, and the shadow of a great calamity seemed to have settled upon them. The remaining rooster, to be sure, was so ungracious as to crow lustily over the bodies of his murdered household, in the presence of all the family. Whistler charitably suggested that this was a song of triumph for his own escape; but Clinton, who knew the jealous rogue better than his cousin did, thought it was quite as likely that he was exulting over the tragic downfall of his rival. Perhaps, however, with the bravado natural to his race, he affected an indifference and stoicism which he did not feel, and crowed, as boys sometimes whistle in a grave-yard, merely to “keep his courage up.”

After the first outburst of regret and pity which the spectacle called forth from all present, their curiosity was thoroughly awakened to ascertain what animal had committed this cruel outrage upon a happy and peaceful family. After a careful examination of the premises, no track or trace of the creature could be found. All was mystery. There was nothing but the slaughtered victims upon which to found a speculation, and these told no tales against their murderer. Clinton was the first to hazard a guess in regard to the assassin.

“It must have been either a fox or a wild-cat,” he said; “don’t you think so, father?”

“If I were going to guess, I should say it was a skunk,” replied his father.

“O, no, father,—a skunk wouldn’t have killed so many of the fowls, would it?” said Clinton, who was unwilling to admit that so common and despised an animal had done the mischief. “Besides,” he added, “we have skunks around here all the time, and why didn’t they ever do such a thing before?”

“If I remember right, they have done just such things before,” replied his father.

“Well, it was a long time ago, before I owned the fowls,” said Clinton.

“It isn’t many months since Mr. White caught a skunk in the act of killing his fowls,” added Mr. Davenport.

“But they have never disturbed our fowls since I owned them, and that is over five years,” suggested Clinton.

“And there is a good reason for that; you have always kept your fowls well secured against wild animals, until this summer,” replied his father.

This was true. Clinton was at first very particular to shut up the poultry at night, so that no animal could get at them; but their exemption from attack for several years had gradually allayed all fears on this score, and of late he had not properly secured his charge from the midnight attacks of their natural enemies.

“Well,” said Clinton, “I don’t believe it was a skunk; I think it was a fox or a wild-cat, or it may have been a ’coon. I mean to borrow Mr. Preston’s trap, and see if I can’t catch him, to-night.”

“I’ll give you fifty cents for his skin, if you catch a ’coon, a wild-cat, or a fox,” said his father, as he turned away from the scene to resume his morning work.

“Agreed; and you shall have it for nothing, if it’s a skunk,” replied Clinton, with a laugh.

“No, I thank you,—I shan’t accept that offer,” replied his father.

“Come, Annie, I wouldn’t look at the poor things any longer,” said Mrs. Davenport, leading her little daughter away.

“Here, mother,” said Clinton, “what am I to do with them? Wouldn’t some of those large ones be good to eat?”

“They may be good enough, for all I know; but I should not like to eat anything that was killed in that way,” replied his mother. “Besides, they are hardly fat enough to eat well. You had better bury them in the garden; I don’t think they are good for anything else.”

“I will do it right away, then,” said Clinton; and he and Whistler procured shovels, and began to dig the holes.

“I should like to see a skunk,” said Whistler; “do they show themselves around here very often?”

“Yes, I see them occasionally,” replied Clinton. “One moonlight evening, last spring, I had been away, and when I came home, I saw one sitting on our door-step; but he walked off as soon as he heard me, and I didn’t think it best to follow him.”

“They are nasty-looking things, I suppose,” said Whistler.

“Why, no; there is nothing very bad-looking about them,” replied Clinton. “Their fur is brown, with white stripes, and if it wasn’t for their odor, they would be hunted for their skins. People sometimes eat skunks when they can’t get anything else, and they say the meat is very well flavored.”

“What kind of a trap is it you are going to borrow?” inquired Whistler; “will it kill the animal, or only make a prisoner of him?”

“It is a steel trap, such as they catch wolves with,” replied Clinton. “It catches the creature by the leg, and he can’t get away, unless he leaves his leg behind.”

“Perhaps you will catch a wolf,” suggested Whistler.

“No, a wolf didn’t do this. He would have eaten or carried off more of the hens,” replied Clinton.

“Don’t you suppose the wolves come down here from the forests, sometimes?” inquired Whistler.

“Yes, I know they do,” replied Clinton. “Last winter two men were in the woods, about a dozen miles north of Brookdale, when a deer dashed out from a thicket, within two rods of them, with a large wolf close on to his heels. Before they could raise their rifles the wolf had the deer by the neck; but they fired, and shot them both dead. I saw both of the animals over to the Cross Roads. The wolf was over seven feet long, and he was a savage-looking fellow, I can assure you. Another man, last winter, was crossing a pond on skates, when a pack of wolves made after him, and, in his hurry and fright, he skated into a hole in the ice, and was drowned.”

“Do the wolves ever come this way in the summer?” inquired Whistler.

“Yes,” replied Clinton; “there are often great fires in the woods, in summer, that burn for weeks, and then the wolves, and bears, and moose, get driven from their quarters, and sometimes they pay us a visit. Mr. Oakley, who lives on the Passagamet river, fifteen miles from here, had ten sheep killed by wolves, about a year ago. A part of the flock came round the house, and looked frightened, and the folks went over to the pasture where the sheep were kept, to see what the matter was. They found seven of them dead, and some of them were torn dreadfully; but three of them were alive, and were hurt but very little. They only had a little scratch on the throat, that looked as if it might have been made with the point of a pin. They carried these three home, and clipped off the wool around their wounds, and washed off the blood, and put on some salve; but they all died in an hour or two. The wolves poisoned them, or else they were frightened to death.”

“And you say bears sometimes prowl around here, too,” said Whistler.

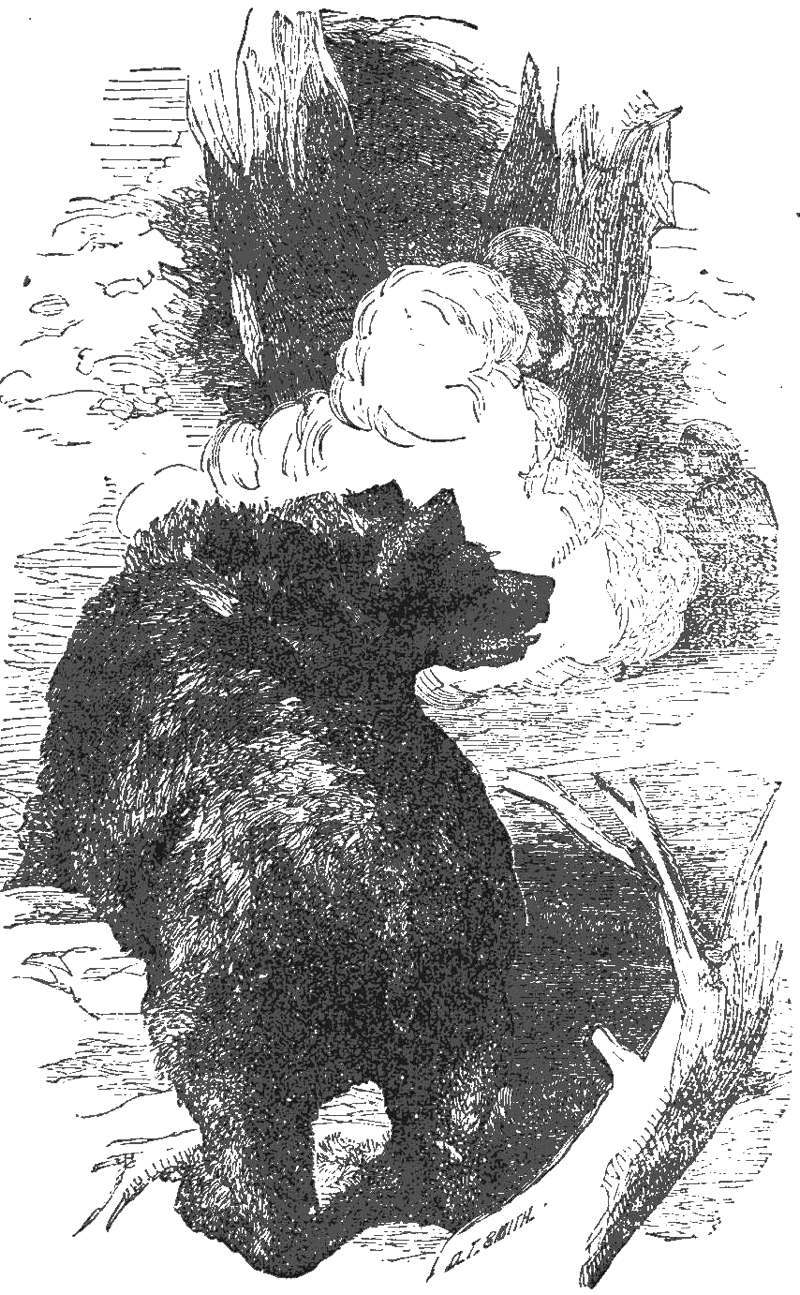

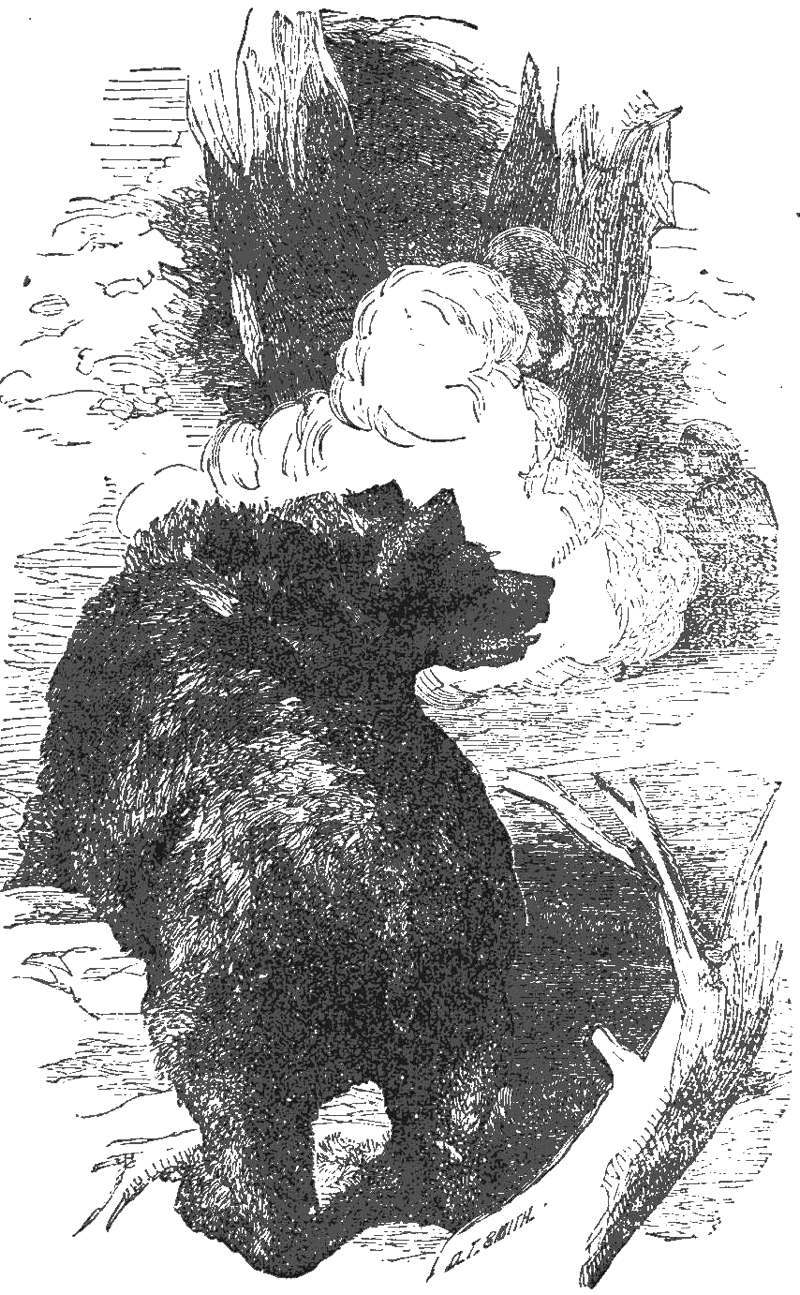

“Yes,” replied Clinton; “four or five years ago, one was seen over in the woods, where we went the other day when we saw Dick Sneider. Last winter father and I rode over to a logging-camp, in a sleigh, and spent two or three days with the loggers. We had a capital time. We ate with the men, and slept on heaps of leaves, in their log huts. They had rousing fires, burning all night, in the middle of the huts; and, instead of chimneys, the smoke went off through a large hole in the roof. But that isn’t what I was going to tell you about. We stopped one night at ‘Uncle Tim’s,’ as they call him, about half way between here and the camp. He lives in a ‘clearing’ in the woods, and there’s no other house for miles around. He told me a good many stories about wild beasts, and one of them was about a bear that he killed last fall. One morning he discovered that some creature had made great havoc in his cornfield in the night, and he found the tracks of a bear all over the lot. He saw, by the tracks, that it was a very large and heavy animal; and, as he had a bear-trap, he thought he would try to catch him with it, rather than have a fight with him. So he baited the trap, and set it in the cornfield; but the next morning he found it just as he left it. The bear had walked all around it two or three times; but he knew too much to go into it, and he made his supper off of green corn again. Well, Uncle Tim said his dander was up, then, and he made up his mind that if the bear got any more of his corn, he should take some of his bullets with it. So, in the evening, he took his rifle, and hid himself among the trees just by the edge of his clearing, pretty near the place where the bear’s tracks were. Well, he waited, and waited, hour after hour, but he couldn’t hear nor see anything of the bear. It wasn’t very dark, as there was a moon. His wife and two boys, and his big dog, were in the house, waiting and watching as patiently as they could; for Uncle Tim told them not to show themselves unless he gave a loud whistle. Well, about one o’clock in the morning, he thought he heard a slight noise, and, sure enough, there was the old fellow within a few feet of him, and looking directly at him. Uncle Tim took good aim, and then blazed away, with as heavy a charge as his gun would bear. The ‘varmint’ gave one spring towards him, and fell dead almost at his feet. He weighed about five hundred pounds, and I don’t remember how much oil Uncle Tim got out of him, but it was a good lot. He got a bounty from the state, too, for killing him.”

“He must be a brave man,” said Whistler.

“O, these old pioneers don’t mind such things,” said Clinton; “they soon get used to bears and wolves. But I saw in a newspaper, the other day, an account of a fight a little boy had with a bear, that was really worth bragging about. He lived near Lake Umbagog, which is on the line between Maine and New Hampshire, and I believe he was only nine years old. He saw a bear in an oatfield, near the house, and he thought he would pepper him with a few buck shot. The bear was wounded, and showed fight; so the little fellow picked up a club, and went at him. The boy’s mother saw the fight, and she gave the alarm to his father and an older brother, who were at work near by; but when the bear saw them coming, he made off as fast as he could. The family gave chase, but they were not well armed, and were obliged to let him escape. Well, a few days after, that same bear was seen near the same place, with a sheep in his mouth; and that same little fellow went at him again, with a club, and made him drop the sheep, and scamper off into the woods. At another time this bear came to the house, when the woman was alone. He put his fore paws on the window sill, and stuck his head and shoulders into the room, and, after he had looked around a little, he walked off without touching anything.”

“That is being a little too neighborly. I shouldn’t like to live quite so near the bears as that,” said Whistler.

“I should want something more than a club, if I had got to meet one,” said Clinton.

“But I shouldn’t be afraid to meet a fox, or a wild-cat, or a ’coon, in the woods,—should you?” added Whistler.

“I shouldn’t want any better fun than to meet a ’coon or a fox,” replied Clinton; “but if I had got to tackle a wild-cat, I should want to be pretty well armed. It isn’t every man that can ‘whip his weight in wild-cats,’ as they say out west.”

“Why, I had an idea they were a good deal like our house-cats, only they are not tame,” said Whistler.[2]

“They do look something like a cat,” replied Clinton, “but they are twice as big, and almost as savage as tigers. I saw a dead one, once. They have little short tails, and very strong, ugly-looking jaws. A boy that lives at the Cross Roads killed the one I saw. He was hunting rabbits, about half a mile from the village, when he saw the head of a strange-looking animal in a tree right over him. He didn’t know what it was, but he concluded to fire; and, just as he did so, the creature sprang right at him. The shot didn’t seem to hurt him much, but he was in a terrible rage. The boy dodged him as he leaped from the tree, and then they had a pitched battle for three or four minutes. The fellow got some pretty hard scratches, and had his clothes torn; but he beat the wild-cat with the breach of his gun until he killed him. He lugged the body home, and he felt as grand as any body you ever saw, for a month afterwards. The wild-cat weighed about twenty-five pounds, and he had the skin stuffed, and has got it now.”

The slaughtered fowls were now all buried, and the boys went in to breakfast. In the course of the forenoon, after Clinton had done his work, he and his cousin went down to Mr. Preston’s, to get the trap. The story of the catastrophe awakened the interest and sympathy of the neighbors, and quite a discussion ensued as to the nature of the enemy that had done the mischief. Mr. Preston said it would not be at all strange if a wild-cat or fox was prowling around the neighboring woods, but he thought it quite as probable that a skunk had killed the fowls. He did not think it was a raccoon, as, he said, this animal eats only the heads of the poultry it kills. As Mr. Preston was an old logger, having spent his winters in the forests for many years, he was well acquainted with the wild animals in that quarter, and Clinton placed considerable confidence in his opinion. Still, he was not quite satisfied that his chickens had fallen a prey to the despised skunk, and Mr. Preston accordingly hunted up his rusty wolf-trap, and gave him some directions in regard to baiting and setting it.

Ella, who listened to this conversation, seemed somewhat alarmed to hear that the woods around Brookdale were ever visited by such strangers; and when Whistler told her that even wolves and bears sometimes came down into the neighborhood, she declared most vehemently that she should not dare to go out of sight of the house again while she stayed there.

“O, yes, you will; you will come over and see us,” said Clinton.

“No, I shan’t; you have wild-cats around your neighborhood,” she replied.

“But Willie and I will come down with guns, and escort you up and back again, if you’re afraid,” added Clinton.

“I hate guns; I should be afraid to go with you, if you carried them,—boys are so careless with fire-arms,” replied Ella.

“Then we’ll come without guns,” remarked Willie.

“Yes; and I’m thinking you would run as fast as I should, if you saw a wild beast coming,” said Ella, laughing.

“No, I shouldn’t, either; I’d stand my ground as long as any body would,” replied Whistler, with some warmth.

“Well, Ella,” said Clinton, “I really wish you would come over once more, before you and Willie go home; and Em, and Hatty, too,—I want you all to come.”

“Well, perhaps we will, after you have caught your wild-cat,” said Ella, as the boys moved off.

“She is pretty good at quizzing,” said Clinton to his cousin, as they walked away. “I really hope I shall catch something; if I don’t play a joke upon Ella, then, no matter.”

“If you do, you will be paid off, with interest, I can promise you that,” replied Whistler; and he related an instance in which Ella “came up” with a boy who took the liberty to play a practical joke upon her.

The day was very warm, and the heat of the sun almost overpowering. Mr. Davenport took a long “nooning,” as was his custom when the weather was oppressively hot. Throwing himself upon a settle, after dinner, in the coolest room he could find, he sometimes indulged in a nap, but more frequently employed the hour of rest with a book or newspaper, or in conversation with his wife or children, or in thinking over the affairs of the farm. On this occasion, Clinton brought in the trap, and showed it to him. After examining it in silence, he inquired:

“How much is your loss, Clinty?—have you figured it up?”

“No, sir; I haven’t thought anything about that,” he replied.

“Then it doesn’t trouble you much, I presume,” said his father.

“No, sir; I care a good deal more for the poor hens than I do for the money,” replied Clinton.

“That’s right!” said his father; “you’ve made considerable profit out of your poultry, and you must expect to meet with some losses, once in a while. Losses are inseparable from business; and the wisest way is to make the best of them when we can’t avoid them. If a man meets with nothing but prosperity, he is apt to grow reckless in his management, and oppressive towards others; or he becomes wholly absorbed with the world, and forgets that there is a God or a future life. But adversity, if a man knows how to profit by it, will correct these faults. I have met with some pretty serious losses in my day; but I can see, now, that I am better off than I should have been if they had never befallen me.”

“Do you think you are better off for being cheated out of everything you owned, when Mr. Jellison failed?” inquired Clinton.

“I have no doubt of it, now, although it was a severe blow to me at the time,” replied his father. “I was a young man then, and had set my heart too intently on making money, as though that were the great object of life. Perhaps, if I had not met with that loss, I should have grown up a miser. I have learned this lesson, on my way through the world: that a man’s happiness doesn’t depend on the amount of money he owns. In one sense, in fact, we do not own anything—we are only stewards. The property is lent to us for the time, and we are bound to make a good use of it. It belongs to the world, or, rather, to God. It was in the world before we came, and it will remain here after we have gone; and we shall have to give an account of the use we make of it while it is in our hands. As I have a claim on all you own, so there is One who has a claim on whatever I possess.”

“But I didn’t know you had a claim on my money,” replied Clinton.

“Have you ever settled for your board, and clothing, and education, and all the other expenses of your bringing up?” inquired his father.

“No, sir,” said Clinton.

“Well, your hundred dollars would not go far, if you undertook to pay those bills,” continued his father. “More than that, the law of the land gives me a right to all your earnings until you are twenty-one years old; did you know that?”

“No, sir; I never heard of that before,” replied Clinton.

“It is so,” resumed his father; “but, in return, the law obliges me to support you, during that time, unless you run away from me, or refuse to obey me. And you will find that this dependence upon others will follow you through life. We never outgrow it, no matter how old or how rich we become. We are all of us beholden to others, but most of all to God, every day of our lives.”

This conversation led Clinton to make an estimate of his pecuniary loss during the afternoon, and he found that it amounted to the sum of five dollars and fifty cents. He showed Whistler his account book, which was kept in a neat and accurate manner. In this book he set down all his receipts and expenses on account of the poultry, and at the close of each year he “struck a balance,” and ascertained the amount of his profits. At this time he had one hundred dollars in a savings bank, on interest, besides about five dollars in his own hands,—all of which his fowls, and the labor of his own hands, had earned him. He also owned his stock of poultry, which, before the disaster of the previous night, he valued at about twenty dollars.

After tea the boys baited the trap, and set it in the garden, near the hen-house. They skilfully concealed it under leaves and other litter, leaving only the bait prominent; and, after watching it from the chamber window as long as there was light enough to distinguish anything, they went to bed, to dream of bears, and wolves, and wild-cats, and to see visions of nondescript beasts not to be found in any work on natural history.