CHAPTER II.

LOOKING ABOUT.

DINNER was on the table when Whistler arrived at Mr. Davenport’s, and he found his uncle and aunt, and his little cousin Annie, ready to welcome him to their hospitalities. These, with Clinton, constituted the whole family. The young stranger soon felt quite at home in their society. He was much pleased with his cousins at first sight, for he had never seen either of them before. Annie, who was about seven years old, was a beautiful child, with golden curls and fair blue eyes, and a face full of gentleness and affection. She seemed to be the pet of the household. Clinton, though but a month or two older than Whistler, was a stouter and taller boy, and his browned skin and hardened hands told that he was not unacquainted with labor and out-door exposure. He had, moreover, an intelligent, cheerful, and frank expression of countenance, that could not help prepossessing a stranger in his favor. The parents of these children Whistler had previously seen at his own house, and he had always numbered them among his favorite relatives.

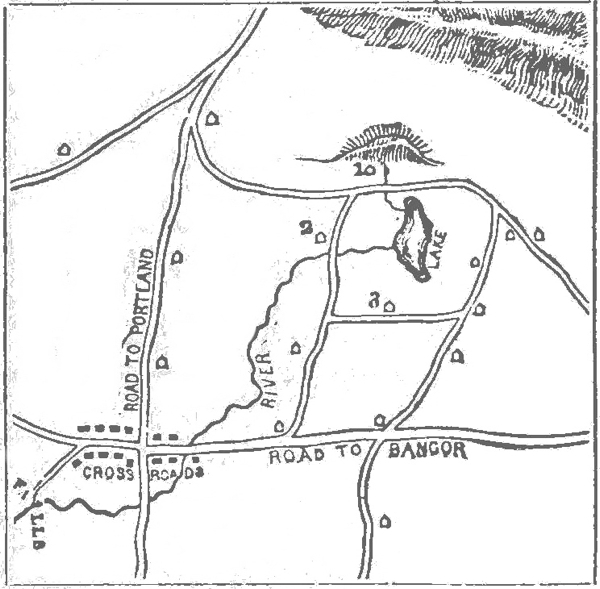

Whistler’s first movement, after dinner, was to make an inspection of the premises. He found that his uncle’s farm lay at the base of a range of hills, and embraced a wide extent of land, a good part of which seemed to be under skilful cultivation. The house itself was set back a few rods from the street, and was pleasantly situated, with its front towards the south. It was a snug, plain-looking building, a story and a half high, with a kitchen and wood-shed attached in the rear. A noble oak tree, in front, afforded a grateful shade; and climbing roses and honeysuckles were trained around the front door, giving a neat and tasteful aspect to the cottage. In the rear, upon an elevated pole, was a perfect fac-simile of the house, in miniature, erected for the accommodation of the birds; and there never was a spring-time when this snug tenement failed to secure a respectable family as tenants for the season. On the next page is a view of the premises.

The barn, which the picture is not large enough to take in, was a short distance from the house, on the left. It was much larger than the cottage, and attached to it were buildings for the hens and pigs.

Clinton, who had been busy, now joined his cousin, and offered to accompany him around the premises.

“This is what we call the shop,” he said, opening the door into a small room adjoining the pantry.

“Why, what a snug little place! and what a lot of tools you have got!” said Whistler.

“Father used to be a carpenter before he went to farming,” added Clinton, “and he has always kept a set of tools. They are handy in such a place as this, where carpenters are not to be had.”

“I suppose you work here some, don’t you? If I had such a place, I should spend half my time in it,” said Whistler.

“Yes,” replied Clinton; “I use the tools a little. There’s a windmill I’m making now; but I don’t know when it will be finished. I haven’t much time to work in the shop in summer.”

“Clinty made this cart for me,” said Annie, who had followed the boys; and she pointed to a neat little wagon.

“Did he? Why, he is a real nice workman,” said Whistler.

“And he made the vane on the barn, and the bird-house, too,” added Annie.

“Can’t you think of something else that I made, Sissy?” said Clinton, laughing at the pride Annie evidently took in his ingenuity.

“Yes,” she promptly replied; “he made the arbor over the front door.”

“Why, Clinton, you are a carpenter, sure enough!” said Whistler. “I should think you might almost build a house; I mean a real house, not a bird-house.”

Clinton smiled at this rather extravagant estimate of his mechanical skill, and led the way towards the barn, through which he conducted his cousin, from the cellar almost to the ridge-pole. The hayloft was very large, and was nearly filled with new-mown hay, the fragrance of which was delightful. Swallows were darting in and out of the great door, and gayly twittering among the lofty rafters, where they had made their nests. A large quantity of unthreshed grain, bound up in sheaves, was stacked away on the main floor, in one end of the barn.

“There’s a good lot of straw,” said Whistler, as they passed by the grain.

“And something besides straw, too; that is rye,” replied Clinton.

“Is it rye?” said Whistler. “Well, I’m just green enough not to know straw from grain, or one kind of grain from another. Father told me I should make myself so verdant that the cows would chase me, and I don’t know but that he was right.”

“They laugh about country people being green, when they go to the city,” said Clinton; “but I guess they don’t appear much worse than city folks sometimes do in the country. I don’t mean you, though,” he added; “for you haven’t done anything very bad yet.”

Whistler broke off a head of rye, and found concealed beneath the bearded points several hard, plump kernels, that had a sweet and pleasant taste. Following his cousin, he then visited the pig-pen, which was behind the barn, and connected with a portion of the barn cellar. Half a dozen fat porkers were lazily stretched about, in shady places, presenting one of those familiar groups that, if they do not appeal to the artist’s sense of the beautiful, do appeal most forcibly to the plain farmer’s sense of lard and “middlings.” If not picturesque, they are decidedly baconesque, which some people consider much better.

“Now you must go and see my biddies,” said Clinton; and he led the way to a large hen-coop, near the piggery.

“Are these your fowls?” inquired Whistler.

“Yes, they are all mine,” replied his cousin. “Father gave me all of his fowls, five years ago, and I have managed them just as I pleased ever since. I have to find their food, and I have all their eggs and chickens. Even the eggs mother uses she has to buy of me.”

“That is a first-rate plan,” said Whistler. “I should think you might make lots of money in that way.”

“This isn’t all,” added Clinton; “I have a flock of turkeys, and a lot of ducks, besides. The turkeys are off, somewhere; they roam all over the farm. The ducks are in that little house down by the brook; we’ll go and see them by-and-by.”

“I should think I was rich, if I owned so many creatures,” said Whistler. “But you have to buy corn for them,—I suppose that takes off the profit, doesn’t it?”

“I haven’t bought a bushel of corn since the first year I had them,” replied Clinton. “Do you see that cornfield, just beyond the brook? That is my field. I planted and hoed it myself, and I shall have all the corn that grows there.”

“But how did you come by it?—did you buy the land?” inquired Whistler, more astonished than ever.

“No, I don’t own the land,” replied Clinton. “Father has got more than he can cultivate, and he lets me have the use of that piece for nothing. He helps me plough and harrow it, too; but I have to do everything else myself. If I want any manure, I pay him for it. If the corn does well, I shall have enough to carry all my fowls through another year. There will be a lot of corn fodder too, that I shall sell to father for the cows; and I have a lot of pumpkins scattered in among the corn, that will be worth something in the fall.”

“Well, you’re a real farmer, as well as a carpenter, that’s a fact,” said his cousin. “How I should like to be in your shoes!—and not in yours, either, but in another pair just like them. Come, don’t you want a partner? I’ll buy in, and we’ll start a new firm—‘C. & W. Davenport, Farmers, Poultry Dealers and Carpenters.’ Won’t that sound tall! What will you sell out one half of your business for? I haven’t much capital, and don’t know much about the business; but I’ll try to make myself useful.”

“I’m afraid you would get sick of the bargain,” replied Clinton. “You’d find it pretty tough work to hoe an acre of corn down there in the sun, when the thermometer is up to ninety in the shade. It’s a good deal of trouble, too, to take care of so many fowls every day, in summer and winter. I like to do it, to be sure; but a great many boys would think they were real slaves if they had to do what I do.”

“It doesn’t take all your time, does it?” inquired Whistler.

“O, no,” replied Clinton. “I suppose it doesn’t take me more than two hours a day, on an average, to take care of my fowls and cornfield; but I do other work besides. I have had the whole care of the garden this summer. Come and look at it.”

They proceeded to a large patch of ground in the rear of the house, which was devoted to a kitchen garden. It had been sown with peas, beans, radishes, lettuce, onions, early potatoes, sweet corn, cucumbers, and other vegetables. Some of the crops had already been gathered, such as the lettuce, radishes, and green peas; and the others seemed to be in a flourishing condition.

“After we had planted the garden last spring,” resumed Clinton, “father told me that if I would take the whole care of it, I might have one fourth of all the profits. I thought it was a pretty good offer, and so I took it up, and I’ve never been sorry for it yet. The garden has done very well, so far. We keep an account of everything that is raised; and next fall I can tell just how much my share will come to. I haven’t had to work so hard as I expected I should, either. I do a little every day, and the weeds don’t have a chance to get the upper hand of me. That is the way to manage a garden. If I should let my work get behindhand, I suppose I should very soon be discouraged.”

“Mr. Preston told us that you did almost as much work as a man,” said Whistler; “and I think he was about right. One thing is pretty certain: you can’t have much time to play.”

“O, no, I don’t work so hard as a man,” replied Clinton. “It only takes about one half of my time to do all my work; but then I have some errands to do, and my lessons to study.”

“I heard about your studying at home, and reciting to your mother: is that the way you do?” inquired Whistler.

“Yes,” replied Clinton; “our school doesn’t keep in the summer, and, as I have some spare time, I study a little at home. Last summer my rule was to study two hours a day; but this year I have had more work to do, and haven’t studied quite so much.”

“What do you study?” inquired his cousin.

“Arithmetic and grammar, principally,” replied Clinton; “but I write a composition once a fortnight and now and then get a spelling or a geography lesson.”

The boys now proceeded towards the duck-house. This was a small, rough shed; but it answered the purpose for which it was intended very well. It was situated near a small brook, and there was a little artificial pond connected with it, in which the ducks could swim when the water in the brook was low. Clinton himself made both the pond and the duck-house, the summer previous. There were about a dozen ducks in the pond, several of which were very small, being but a few weeks old. They gracefully sailed off as the boys approached; but when Clinton spoke to them they recognized his voice, and wheeled about towards him.

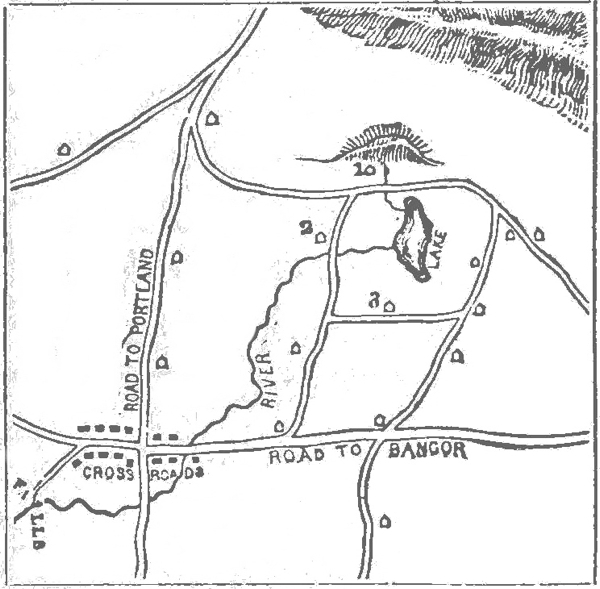

Having visited the principal objects of interest on the farm, Whistler began to manifest some curiosity about the geography of Brookdale. He got a pretty good idea of the natural features of the town, by ascending a high hill back of his uncle’s house. Before him lay a beautiful lake, or pond, as the Brookdale people called it, which looked like a bright mirror set in emerald. A narrow river, glistening in the sunlight like a silver thread, stole along through the meadows towards the southwest. There were but a few widely scattered houses in sight, for Brookdale was only a small farming settlement. On the north and east the view was hemmed in by high hills, covered with trees; but in other directions the prospect was extensive. Clinton pointed out to his cousin a mountain which he said was twenty miles distant. It looked like a faint cloud on the horizon.

But I can give you a better idea of the geography of Brookdale by the aid of a little map, which will show you at a glance an outline of the objects which Whistler saw from the hill, and also some things which he could not see from that position. The house numbered 1 is Mr. Davenport’s, and behind it is the hill from which Whistler obtained his view. No. 2 is Mr. Preston’s house, and No. 3 is the schoolhouse. The map shows the position of the lake, the river, and the brook near Mr. Davenport’s house. It also shows the Cross Roads village, and the principal roads passing through the town.