CHAPTER VII

REAPING THE HARVEST

A roaring black cloud that looked almost like the vortex of a tornado swirled over the log barn. There was a smaller cloud hovering about the house, and the whole clearing was alive with bees, coming and going, looking for something, all extremely irritable.

Approaching the barn as closely as they dared, they saw that the whole building was like a vast beehive. The insects covered the logs; they swarmed in and out of every one of the wide chinks between the timbers. Myriads were continually emerging and flying off, and myriads more took their places.

“Gracious!” exclaimed Carl, looking rather wildly at his brother. “I didn’t know we had so many bees. The honey’s here in the barn all right.”

“It won’t be here long, at this rate,” returned Bob. “But I wonder what’s happened to Larue and his family and live stock. Perhaps they’re all dead!”

The boys really felt seriously uneasy at the overwhelming success of their scheme. Except for the bees, no living creature was in sight, but Carl presently spied a dead hen near the barn. Evidently she had been killed by the bees, and this increased their uneasiness. Bob made an attempt to reach the cabin, but a host of savage bees drove him back, despite his veil. The insects were fighting-mad.

The boys crept around the edge of the clearing, keeping in the shelter of the woods, where the bees did not molest them. They had made about half the circuit when they caught sight of a heavy cloud of smoke rising a little way back among the thickets.

“S-sh! There they are!” whispered Bob.

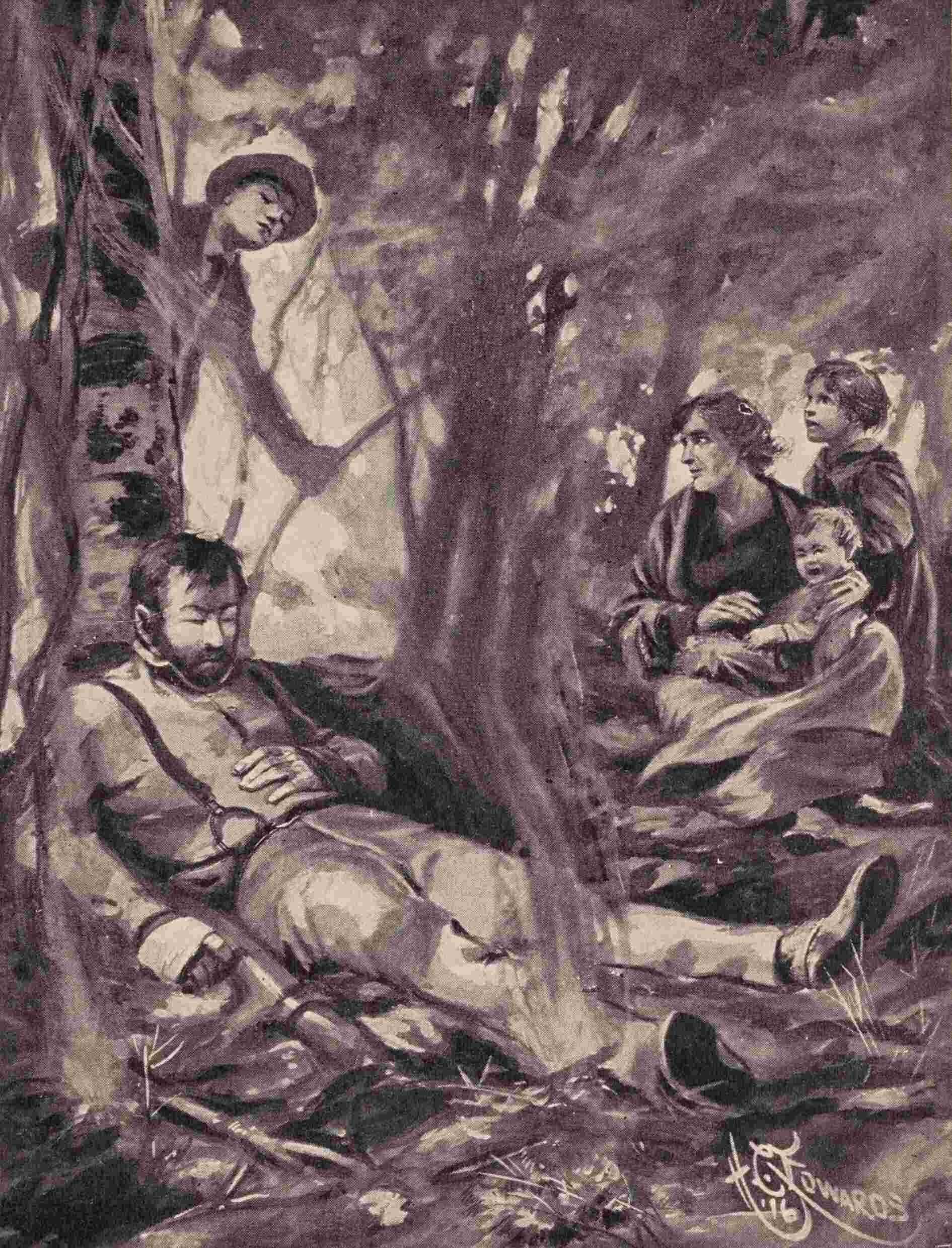

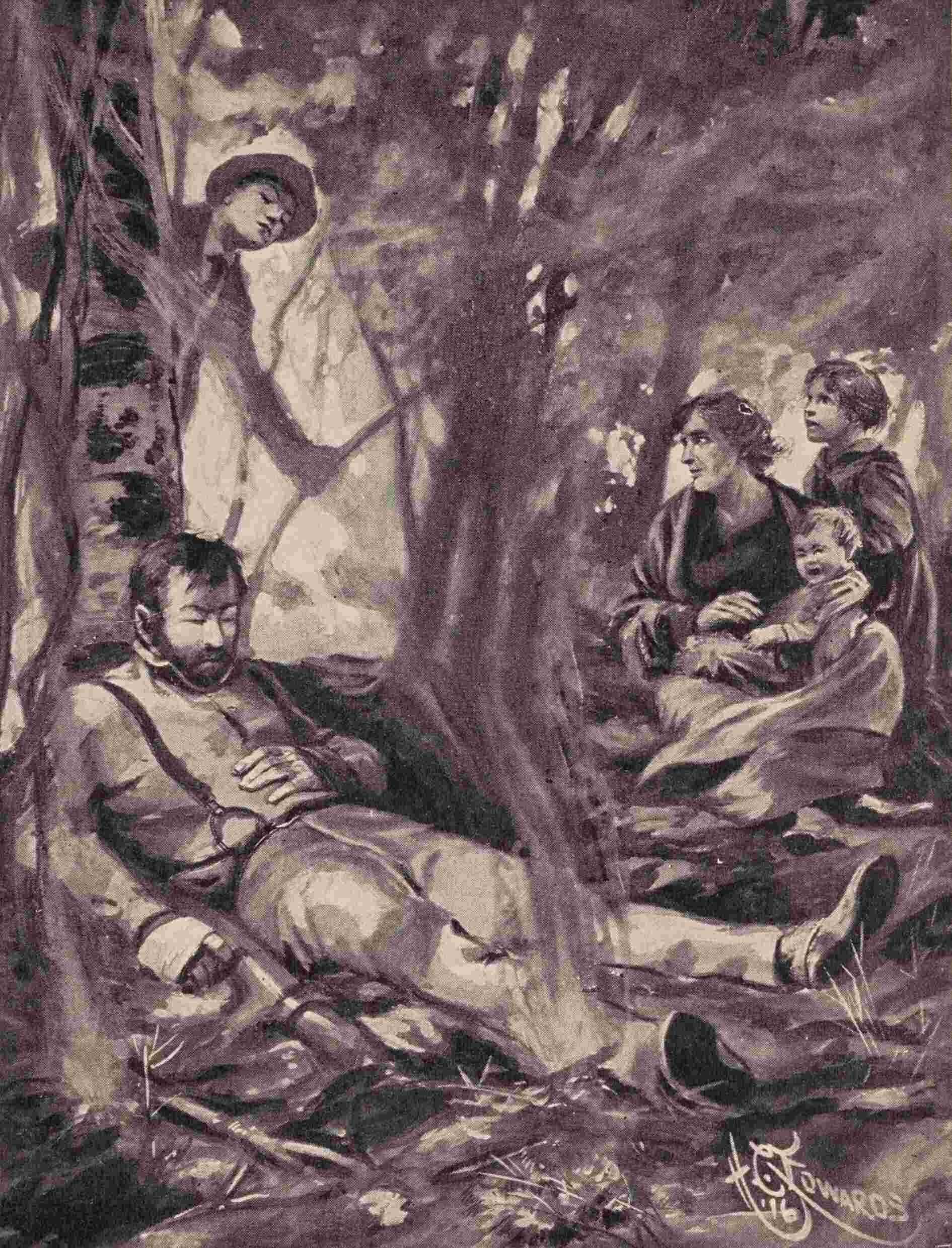

They lay low for a minute, then, hearing no sound, crept up close enough to gain a view of the camp. The squatter’s family were sitting dejectedly in the shelter of smoke from a heavy smudge. Larue himself reclined against a tree, but he was hardly recognizable. Both his eyes seemed to be swollen shut. He had two big lumps on his forehead, his lips were puffed, and one ear was twice its rightful size. It was clear that he was in no fighting condition, and the boys walked up without any hesitation.

He was plainly in no condition to show fight, and the boys advanced without hesitation

“You seem to be having trouble,” said Bob innocently.

The squatter tried to screw his eyes open far enough to get a glimpse of them.

“Nom d’un nom!” he ejaculated, thickly through his swollen lips. “Dose bees! Dey come—dey swarm—!” and he trailed off into a mixture of French and English indistinguishably distorted in his puffy mouth. They could hardly make out a word.

“What’s been happening, Mrs. Larue?” said Carl, turning to the woman. She also bore marks of stings, and so did the two children.

“Your bees!” she cried. “Dey come in by t’ousands—millions! We stay in de house—no! Pas possible! Dey kill my two best poulets. Kill us too, if we not get out!”

“What do you suppose they could have been after?” asked Bob.

The woman cast a quick glance at her husband, and said she didn’t know, but in her queer dialect she gave an excited account of what had happened—from her point of view.

That forenoon they had suddenly been invaded by a whirlwind of bees. The family had tried at first to shut themselves up in the house, but the bees forced an entrance through hundreds of crevices, and they had had to take to the woods. Larue had been terribly stung while trying to get a cow out of the barn, and two hens had been killed by the bees. Afraid to leave cover, the family had been sitting all day under the smudge-smoke, without food, not daring to go to the house to find any. She knew, of course, that these were the Harman bees, but the boys were relieved to find that she seemed to have no sort of suspicion that the raid had been planned.

“We must get this thing stopped,” whispered Carl, drawing his brother aside. “The bees’ll kill everything on the place.”

“Yes, and after dark we can carry away the rest of the honey ourselves,” replied Bob. “These people won’t try to stop us. In fact, now will be a good time to try to make up a peace with them.”

“You’ll be all right by to-morrow, Mr. Larue,” said Carl, reassuringly. “Perhaps you know better than we do what attracted the bees down here, but we’ll try to fix it so they won’t bother you any more.”

“I move away from zis place!” cried the squatter, energetically. “Ze bee—he make my life one misery!”

“Well, I’m sorry it happened,” returned Bob. “Here’s a dollar to pay for your two hens, and we’ll send you some honey—for the children.”

The woman took the dollar bill, muttered a word of thanks, but did not seem much propitiated. As for stopping the raid, the boys could do nothing till the bees stopped of themselves for the night. It was really dangerous to venture out of the shelter of the woods. Even sunset brought little cessation of the uproar, and it was not till it was quite dark that the bees gradually ceased to hover about the barn and cabin.

Bob and Carl then accompanied the Larues to their house, which was strewn with dead and half-dead bees. On the table were several unmistakable pieces of section honey, which the boys wisely pretended not to see. No doubt Larue had brought them in for breakfast, but the bees had taken all the honey out of the combs. After finishing the honey, they had licked up everything sweet in the house, including two quarts of maple syrup and a jar of raspberry jam.

The barefooted children were at once stung by treading on the stupefied bees that crawled over the floor. Larue flung himself down on the bed and started up again instantly, with a loud ejaculation. There were bees in the bed, too. The woman took a broom and began to sweep the insects out, but the boys judged it more politic not to stay.

“Can you lend us a lantern?” inquired Bob. “We want to look into the barn. There’s some honey of ours there that we want to take away. When it’s gone, the bees will leave you alone.”

“Oui, I get you ze lantern,” said the woman. “Look in ze barn. Look anywhere. But I see no honey. I know nottings about it. I get you anyt’ing, only you take dose bees away.”

Though the bees had ceased flying, there were many of them still crawling about the log barn, and in the lantern-light they perceived a big pile of something lightly covered with hay.

“There it is!” exclaimed Carl, with satisfaction.

It was indeed the stolen shipping cases and supers, and the hay covering had not prevented the bees from getting at them. At a glance the honey seemed to be all there. At the worst, not many of the sections were missing, though the honey was presumably all cleaned out of them. There were a good many bees still in the boxes, and the floor was covered with dead insects. Evidently they had fought ferociously over the plunder.

“Quite a load of stuff to take home in the boat,” remarked Carl, as they surveyed the rescued honey.

“Yes, but if all the honey is out of it, it won’t be heavy, I fancy,” said Bob. “I saw an old wheelbarrow around here, and we’ll use it to take the stuff to the boat. We absolutely must get it all home to-night, before these people recover from their shock.”

The top cases of honey were indeed light, and seemed to contain nothing but empty combs—hardly that, in fact, for the wax sifted out in fine powder, for it had been torn to pieces by the frenzied bees. But as they went deeper the boxes grew heavier; some of them seemed almost full weight, though no doubt they were all damaged enough to be unsaleable.

It took three boat-loads to get the honey back home, and it was hard and heavy work pulling it up against the current. Alice was jubilant, and when they came up with the second load she had a supper of bacon, trout, cold partridge, and hot coffee ready for them. They needed it; food had never tasted so good; and after finishing everything in sight, they went back for the last load.

“We ought to bring those six hives of bees home, too,” said Carl, uneasily.

“I suppose we should, but who cares?” replied Bob. “I’m dead tired, and I wouldn’t row up that river again for a whole apiary. Larue doesn’t know where they are. We’ll bring them up at sunrise in the morning. I’m going to bed.”

But it was then considerably after midnight. The boys overslept, and did not waken till eight o’clock. The bees at home were flying already, showing signs of much excitement, and could be seen going down the river as on the day before. They were still looking for stolen honey.

“Won’t they hang around and bother the Frenchman again to-day?” Bob asked.

“I’m afraid so,” said Carl. “But it can’t be helped, and they’ll soon find that there’s nothing more to be had, and go about their business. It’ll be better when we get those six hives home.”

It was after nine o’clock when they reached the ambushed hives, and at the first glance Carl uttered a loud cry of dismay.

“Why, they’re all shot to pieces!”

They both ran up. One hive was overturned, with a great, splintered hole blown through its side; a second was nearly as bad, and all the remaining four had been more or less perforated with buckshot. Honey had run out on the ground, and the bees were crawling about stupidly, seeming too much disconcerted to gather it up.

“Looks as if Larue had got his eyes open again,” said Carl, as they surveyed the wreck.

“Yes, and he’s on the warpath!” Bob lamented. “Just when I had planned to make peace with him! I hoped he’d never find out that we had engineered this riot, and we’ve paid him for his hens, and I was going to send him some honey to sweeten him up. And now it’s all off.”

“Well, I don’t believe this is a particularly safe spot for us if he’s out with his gun,” said Carl. “Let’s get these hives moved away.”

First Bob peeped through the thickets into the clearing. A good many bees still hung about the barn and cabin, and no doubt they were fiercely cross at finding no honey where they had expected it. There was no sign of the French family; very likely they were under their smudge again.

“I can’t say I blame Larue for being mad,” said Bob, “after being driven out of his house for two days running. I suppose he expected to find all quiet this morning, and it’s almost as bad as ever. Then he found these hives and he naturally bombarded them.”

“Well, if he hadn’t brought our honey down here it wouldn’t have happened!” returned Carl, hard-heartedly. “He’ll bombard us, too, if we hang around here long.”

They carried the dilapidated hives down to the boat with a good deal of difficulty, and rowed them up-stream. Two of them were ruined, but it was likely that the bees themselves and the combs would do very well if lodged in fresh hives. The outfit was nearly double its former weight and a later investigation showed that the bees had crammed every available cell with honey and had built fresh scraps of comb in any corner where there was room.

On their return Alice met them with a joyful face.

“What do you think?” she cried. “I’ve been sorting over the cases of sections you brought back, and there are a lot that haven’t been touched by the bees at all—perhaps three or four hundred; and there are quite a lot more that have only little torn places; so they can go as ‘No. 1’ anyway. Then there are all the sections that weren’t stolen at all. We’ll still have some honey to sell.”

“Maybe a hundred dollars’ worth,” returned Carl. “That won’t go far toward our big payment next week.”

“Yes, it will—with our extracted honey,” urged Bob. “We must get it all off, extract every drop we have, and sell it quick—sacrifice it if necessary. Anything to get returns at once!”

“There must be four hundred dollars’ worth on the hives. We can make the payment, if we’re quick,” said Alice.

“Anyway, we won’t have a cent left over,” insisted Carl, who seemed determined to look on the black side.

“But we have the bees. Next year they’ll make our fortunes,” said Alice, cheerfully.

Tired as he was, Bob paddled down to Morton that afternoon, wrote a letter of explanation to Brown & Son, and ordered by telegraph nine hundred five-pound honey pails, to be shipped by return freight. The pails cost forty dollars, and he groaned inwardly as he parted with the money.

It was with some uneasiness that he navigated his boat past the squatter’s clearing, but he saw nothing of any of the Larue family, either coming or going. When he got back to the bee-yard he found that Alice and Carl had been busy. They had brought in the old honey extractor, cleaned and oiled it and set it up, along with the honey-tanks. Carl had improvised an uncapping-box from the rain-water barrel, and they had already extracted the honey from a great number of the damaged and unfinished sections of comb.

The three of them finished up that part of the work during the afternoon and cleaned out all the honey from the unsaleable sections and from those that the bees had torn in Larue’s barn. From these they got more than a thousand pounds of fine, clear honey. It was an excellent beginning.

But it was only a beginning. In five days they would have to pay Mr. Farr five hundred dollars with interest. To sell the honey might well take two days. Consequently they had something more than two days in which to take off, extract, and pack a crop of perhaps four thousand pounds of honey. It would have been a fairly large undertaking for skilled men, and the Harmans were quite unaccustomed to extracting on a large scale.

But they had determination enough to make up for lack of experience. They went to bed early, in order to have as long a rest as possible. By daylight Alice was preparing breakfast, and the sun was not more than fairly above the trees when they attacked the big job.

Armed with veils, gloves, smokers, and bee-brushes, the boys went out to the yard, while Alice waited for the honey to come in. The big extracting supers were full of bees, that rushed up furiously when the cover was lifted off. Carl drove them down with smoke, while Bob quickly lifted out comb after comb, shook and brushed off the bees in masses before the hive, and put the combs into an empty super. When that was full, he carried it with some difficulty into the house. While he was gone Carl removed the now vacant super, closed the hive, and smoked another. Bob came back in a moment and cleared the bees from this super, carrying it likewise into the cabin. Super after super came off, and when seven or eight of them were stacked in the honey-room they began extracting operations.

Alice had volunteered to do the uncapping, as she had been accustomed to do it at home, and she had the huge, razor-edged honey-knife already standing in a pail of hot water, since the edge cuts much better when warm enough to melt the wax.

She rested one of the full honeycombs on the rim of the barrel, and with a single sweep of the great knife she sliced off the entire outer sealed surface of the comb, so as to leave the cells open. Repeating this operation upon the other side, she handed the comb to Carl, who slipped it into the extractor. When four combs had been uncapped and put into the machine, he turned the crank vigorously. The reel whirred as the combs spun round; impelled by centrifugal force, the honey flew out of the cells against the sides of the extractor and dribbled slowly down to the bottom.

When he stopped the machine to take out the now empty combs Carl put his finger down into the extractor and scraped up a dripping fingerful of honey, which he put into his mouth.

“Delicious!” he exclaimed, with high appreciation.

Meanwhile Alice had uncapped a fresh set of four combs, and a pool of honey was forming in the bottom of the extractor. It was so thick that it ran very slowly down the sides, but within a few minutes it stood several inches deep. Bob drew off a pailful through the gate, and poured it through the cheese-cloth strainer into one of the tanks. It was almost water-clear, thick and rich—honey of the very highest grade.

Bob then returned to the hives and began to bring in supers single-handed, taking back the sets of emptied combs and replacing them on the hives. He was able to attend to this duty as fast as Alice and Carl could uncap and extract. At noon, when Alice stopped work to prepare dinner, they had extracted almost six hundred pounds of honey. It was the harvest from fourteen hives.

“Why, that isn’t half bad,” said Alice, after making this calculation. “That amounts to about forty-five pounds per hive. Better than I expected from this poor season.”

“We may have more honey than we think,” said Carl, brightening. “But we must get ahead faster, or it’ll take us all the week.”

During the afternoon they managed to empty the supers of twenty-one colonies. But these were not quite so well filled, and yielded only a little more than seven hundred pounds.

That night it rained—the longed-for rain, now too late to be of service. Early the next morning they set to work again, but had to stop taking off honey on account of a fresh downpour. In the midst of the rain the wagon arrived from Morton with the nine hundred honey-pails.

“Couldn’t we send some of it back with him?” suggested Alice.

So they begged the teamster to wait a few hours, and set to work furiously, filling the tins from the tanks. Bob sat by the tank with a mountain of five-pound pails beside him, filling them rapidly from the open honey-gate. Once full, he passed them to Alice, who wiped them clean and put on the covers; then Carl nailed them up again in their shipping crates.

At noon they ate a hasty, cold luncheon, and again set feverishly to work at the pails. They made such speed that at four o’clock they were able to start the wagon back with a load of two hundred five-pound pails of honey.

The rain had stopped, and they began to take off honey and extract again. They were getting rather tired, and the task before them seemed endless. It was the twenty-ninth of the month. It seemed hardly possible that they could put up all that honey and turn it into cash in less than three days.

All that afternoon they toiled, weary and silent, but still determined. The uncapping barrel was nearly full of oozy masses of comb, from which the honey drained slowly into a pail through a hole in the bottom. The three Harmans were smeared to the eyes with honey. They were stiff with stings, too, for the whole room was crawling with bees that had been brought in on the combs. They were underfoot, on the walls, in the cappings and the strainer, and a great mass had clustered on the window like a swarm.

By six o’clock there were scarcely half a dozen hives left uncleared in the apiary, though a large pile of unhandled supers had accumulated in the workroom. They stopped work, and the boys helped Alice to get supper.

“But we’re not going to get through in time,” said Bob, anxiously. “It’ll take us nearly all of to-morrow to extract and can up the rest of the honey. Then it’ll take some time to get it sold.”

“But we’ve got to get through in time!” cried Alice. “Are we going to fail now by just a few hours?”

“Well, let’s finish the extracting to-night—work till it’s done,” Bob proposed.

“All right,” replied Carl, wearily. “I’m game!”

So after supper they attacked their task afresh. The boys tried to get all the supers into the house while daylight lasted. They worked hard, but the last supers were very heavy, the bees were cross as night came on, and darkness had fallen before they got the last one in. Alice placed several beeswax candles about the room, and they began to extract.

Hour after hour the whir and rattle of the extractor went on. It was almost the only sound in the room, for they were too tired to talk. The pile of full supers went down, and the empty ones went up, till they clogged the room, and had to be carried outdoors. Alice uncapped till she could no longer hold the slippery knife-handle, and Carl took her place, while she drew off honey from the extractor into the tanks. It was hot in the choked little room, reeking with the odor of honey and the smell of the candles and the tankful of wet cappings, and occasionally they went outdoors for a few minutes to cool off and breathe a little.

“Alice said that bee-keeping was kid-glove work—nothing heavy or hard about it,” remarked Carl ironically during one of these rests.

It seemed to be tacitly understood that they were to keep at it till the honey was all extracted, and they stayed doggedly at work despite weariness and stings. It was shortly after one o’clock when they emptied the last super; they were all saturated with honey and perspiration; the uncapping tank was heaped with wax, and the candles had burned low. All the tanks were brimful, and there was over a hundred pounds in the reservoir of the extractor.

“Going to can it up?” asked Carl, faintly.

“Not much!” Bob ejaculated. “I’m going to bed.”

They were all ready to go. Alice retired to her room, and the boys spread blankets on the floor of the living-room. They were tired enough to doze the moment their heads touched the pillow, but Bob had not been in bed for five minutes when he bounced up with a yell. A bee had stung him on the leg.

The floor and the blankets were alive with bees. Bees seemed to be everywhere. The boys shook out their bedding, swept up the floor, and tried again. There were fewer bees now, but still enough to make their presence felt, and finally the boys became nervous and wakeful, imagining that they felt crawling bees even where there were none. After a restless half-hour Bob got up and lighted a candle.

“I can’t sleep. I’m going to can up honey,” he announced.

Carl wearily followed him, and after they had been at work a few minutes Alice came out and joined them. There had not been so many bees in her room, but more than enough to make sleeping impossible.

Hour after hour they drew off honey from the big tanks into the little pails, and packed them in the crates. They worked till after three o’clock, stopped for hot coffee and bread, and completed their great task soon after sunrise. There were altogether 675 five-pound tins, beside the two hundred already sent to Morton—a total crop of 4375 pounds. At least fifty pounds more would still drain from the uncapping tank.

But they were too dead weary to rejoice. They ate a hastily prepared breakfast, then carried the blankets to a sunny spot outdoors and went sound asleep. Not one of them woke till nearly noon, when they were aroused by the hallooing of the teamster, who had been ordered to come back that day for another load.

It made a big load, and the man was unwilling to take it. But they could not think of another day’s wait, and finally persuaded him with arguments and increased pay. Bob was to go out with the load, they had agreed. He was to ship the honey and go to Toronto with it. There he was to make the quickest possible sale and send the money back by telegraph.

“You’d better come over to Morton on the first of August, day after to-morrow,” he said to Carl, as he was leaving. “Probably you’ll find the money waiting for you at the telegraph office. If it isn’t there, wait at the hotel, and I’ll telephone you some time during the day. In case there’s any delay, get old Farr to let us have a few days’ grace. He ought to do that, especially if we pay him for the accommodation.”

Bob went off on the loaded wagon. Carl and Alice were too thoroughly tired to feel inclined to clear up the sticky litter in the extracting-room and they spent most of the day in sleep.

Next morning, however, they put things in order. The tank of wet cappings was left to drain still longer, but Alice washed down the floor, removed the extracting outfit, and restored the boys’ bed. All the live bees in the room were by this time clustered in a quiet lump on the window, and Carl was able to brush them off gently into a bucket and carry them out to a hive like a natural swarm. He put most of the wet supers back on the hives whence they had been taken, and was surprised to notice that the bees paid no attention to these fresh, sticky combs when they were exposed in the yard. A little honey seemed to be coming in. He could not guess its source, but it was enough to keep the bees from robbing.

All this did not take them more than a couple of hours, and Alice had even time to wash, dry, and iron a blouse before starting for the village which represented civilization for them just then. Carl also paid civilization the homage of brushing his shoes and putting on a tie under his low collar, and then they made an early start down the river.

They rather disliked to leave the cabin unguarded, but this time it contained little of value. As they passed Indian Slough they spied Larue on the shore; he looked long and steadily after them, but neither made any sign.

“Don’t like it!” remarked Carl. “He knows we’ve gone away now, and goodness knows what he may do to the bees!”

“I don’t think he’ll touch them. He must have had enough of fighting bees,” returned Alice.

Anyhow, it was a chance that had to be taken, for they could not stand on guard by the apiary forever. They reached Morton about ten o’clock and went straight to the telegraph office, where they were bitterly disappointed to find no waiting message from Bob.

A feeling of impending misfortune crept over both of them. They had fully expected the money to be there.

“I do hope Bob doesn’t try one of his wild bluffs for a high price and miss a sale altogether!” Carl muttered.

Alice went to the hotel, to be on the lookout for a telephone call, while Carl hung about the telegraph office. At every clicking of the keys he thrilled with anticipation, but noon arrived, and one o’clock, and still no word from Toronto. Carl then hunted up Mr. Farr and explained the situation.

“I don’t know why Bob hasn’t wired,” he said, “but we’ve got the honey and it’s as safe as money in the bank. It’s only a matter of a few hours, or days, at the most. If you’ll give us a little extension of time we’ll gladly pay you for it. Anything you wish, five dollars, or ten dollars a day, even.”

But the postmaster shook his head with a grim smile.

“I’ll give you all the time the law allows, and not an hour longer!” he said.

“Yes, but can’t you—”

“No, I can’t. I told you out and out at the start that you’d get no kindness from me—straight business and nothing further.”

He refused to hear a word of Carl’s protestations, and at last the boy went to the hotel, indignant and keenly anxious. Alice had had no message. They waited, staying near the telephone, unable to read, unable to talk, till, about four o’clock, a call came for Carl.

Almost breathless, he took the receiver, and recognized Bob’s long-distance voice.

“Is that you, Bob?” he cried. “What have you done? Farr won’t give us an hour’s time.”

“Never mind!” came his brother’s reassuring voice. “It’s all right. I sold at ten and a half. I’ve got the money and I’ll wire it at once.”

Ten and a half! They had not expected to get over ten cents for the extracted honey. Carl almost shouted, and Alice gasped with relief when he told her. It seemed as if a mountain’s weight had been lifted off their shoulders.

But there must have been some delay about sending the money, for it had not arrived by six o’clock. Carl hung about the telegraph office all the evening, growing uneasy once more as hour by hour went by. Surely something had not gone wrong at the last minute!

But the money-bearing message did finally arrive towards ten o’clock. It was an order for $612, which included the returns from what was left of their comb-honey crop. The telegraph clerk wrote a check, and Carl and his sister hastened to Farr’s house. It was dark from top to bottom. Carl knocked loudly once, twice. There was no reply.