CHAPTER IX

STOPPING A WAR

Bob hurried through the debris of dead timber till he got a clear view of the bee-yard. It was plain enough that something was seriously wrong, for the whole place was in a state of wild disorder. The air was full of circling bees, and the white fronts of most of the hives were brown with masses of bees, crawling and surging excitedly. One hive near him was actually almost hidden by the cloud that hovered about it. It looked as if a swarm was coming out, but Bob knew better. It was war in the apiary. The bees had gone on a robbing riot, and this hive had been overcome and was being sacked.

How this fearful state of things had started, Bob was unable to imagine. To be sure, there had been no honey coming in lately, and bees will always rob if they get a chance in a honey dearth; but all the colonies at this yard were now strong and should have been well able to defend themselves. Bob could not think how matters had ever got in such a state as this.

Advancing a little incautiously, a bee stung him on the nose, and he dodged back again into the shelter of a thicket. Keeping under cover, he skirted about the apiary, viewing the scene carefully, till at the other end he came upon the clue to the mysterious rioting.

Two hives had been upset, and supers, combs, covers, and bottomboards lay strewn about the stony ground. What had done it he could not guess. The thought of Larue passed through his mind, but this hardly looked like the work of any human honey-thief, for the parts of the hives were tossed pell-mell, and frames and combs were smashed and crushed on the ground. He was too far away to get a good view and was afraid to go nearer, for the air was alive with half-maddened bees. Not many bees appeared about the wrecked hives, however; and probably every drop of honey had been licked up from them long ago, but there was no doubt that all this broken honey in the yard had started the rioting.

There is something about stolen honey, especially when it is obtained close to the hives, that causes bees to become almost insane—sometimes entirely so. Virtually every hive seemed to be engaged in repelling robbers and trying itself to rob other colonies. The ground was covered with knots of fighting insects; in front of the hive that was being sacked there was fully a quart of dead and dying bees that had perished in the battle. As soon as this hive had been cleaned out the robbers would attack another, in greatly increased force, and after that a third.

Bob had no means of knowing how long this state of things had been going on, but it would greatly reduce the apiary if it continued much longer. He knew well what he ought to do; the colonies doing most of the robbing should be smoked well to take the courage out of them; the colonies that were being robbed should have wet grass piled all around the entrance. But he needed a veil, for it was really as much as his life was worth to venture unprotected into that cloud of maddened insects. Gloves would be useful, too, but above all he needed a smoker.

All these things were stored in the little hut that they had made in the center of the bee-yard, but to get to it he would have to pass right through the thickest of the fighting. He hung back for some time, hesitating and reluctant. He wished vainly for his brother, but at last he made up his mind, pulled his hat over his eyes, buried his hands in his pockets, turned up his collar, and made a bolt for the little storehouse.

He shot between the rows of hives so fast that for ten yards nothing touched him. Then he was stung on the chin, and again on the nose. But he had almost reached the hut when something caught him by the right ankle with such force that it seemed to break his leg. He tumbled headlong with a sharp cry, fell against a hive and knocked it sideways.

Fortunately it did not overturn, but a gust of savage bees surged into his face. He brushed at them, and tried to get on his feet. Something that hurt extremely was hanging to his right foot. He made a blind leap to get away from that vortex of stinging insects, but was pulled up short by the ankle and fell again, with a rattle of metal. And now he saw the great, rusty steel trap gripping his foot. He had walked squarely into Carl’s bear trap. He had forgotten that it had been set in this yard.

For the moment he was too bewildered to realize more than this bare fact. He crawled away as far as the chain would let him, lay flat on his face and tried to protect himself from the tormenting insects. It seemed to him that all the bees in the yard had turned upon him. They were in his hair, they got under his collar and up his sleeves. Probably there were in reality only a few hundred attacking him, but it seemed to him that he got a fresh sting every second, till his whole body was in agony.

He drew his foot under him to examine the trap, and see if it could not be taken off. Age and rust had taken a good deal of the strength out of the springs, and, luckily, Bob was wearing heavy shoepacks that day with his trousers tucked inside them, so that the combined thicknesses of stout leather, cloth, and socks had deadened the force of the springing jaws. But it hurt extremely; his foot was numb, and he could not see how to extricate himself.

He tried to press down the springs with his hands, but he was not strong enough. It needed a lever to set that trap. Reckless of stings, Bob stood up and tried to stamp down the spring with his free foot, but in his constrained posture he was barely able to stir it. It would certainly take a lever to open the jaws. If he could only escape into the security of the woods, away from these maddening bees, he felt sure that he could contrive to get himself free, but the chain would let him go no farther. The chain was riveted to the trap in a heavy swivel, and the other end was attached to a stout maple sapling. The tree was too large to break off, but Bob had a stout pocket-knife and thought he might hack through it if he had time enough.

But he was beginning to feel sick and dizzy with the stinging. A professional bee-keeper thinks little of being stung, and Bob was pretty well hardened to it by this time, but not to such wholesale doses. His body was beginning to feel numb all over, and his tongue seemed swelling in his mouth. A horde of bees, he thought, roared and crawled over him, but his brain seemed stupefied, and he could hardly think connectedly of anything.

The idea dawned upon him that he was really going to be stung to death, and the horror of it whipped his brain to a last effort. He cast about for some expedient. If he only had a smoker! But why could he not make a smoke without one?

Instantly he struck a match and dropped it into a heap of dead leaves that lay beside him. They flamed up, and at the first puff of smoke the bees about his head drifted away. He piled on more leaves, using the dampest he could find, and created a suffocating cloud of smoke. He choked in it himself, but there were no bees about him now, except a few entangled in his clothing.

He crawled toward the maple sapling, raking the burning smudge along with him. Under cover of the smoke he began to whittle into the hard trunk with his knife. Between the thick smoke and a bee-sting that had nearly closed his eye, he worked rather blindly, and had hacked nearly half through the trunk before he discovered that no such work was necessary. The chain was merely wound around the tree a few times and hooked back into its own links. He might have known that it would be so fastened, and if he had been a little more clear-headed, he could have released himself a moment after being caught.

However, he cast the chain loose immediately and began to hobble toward the woods, trap and all. Once under cover, he pried open the trap without much difficulty, using a stout pole. There was a deep purple furrow on each side of his ankle, and his foot was blue and numb. He rubbed it a long time and bathed it in the lake before feeling came back to it.

He felt decidedly weak and shaky and had to take off all his clothes in order to get rid of the bees that were still crawling and stinging in their recesses. Being stripped, he ducked himself in the cool lake three or four times and felt better. Naturally, he selected a spot for his bath that was at a safe distance from the apiary, where the war was still raging.

He sat down and rested for half an hour after dressing, and then felt recovered sufficiently to make another attempt at subduing the fighting bees. It was imperative that the disorder be stopped at once, and his late experience had given him a hint how to do it.

Going to the windward side of the yard, he collected rubbish and lighted a number of smoky fires, so that the smoke drifted across the hives. Under cover of this smoke he advanced further into the yard and lighted more fires, till the whole apiary was veiled in clouds of vapor.

Fighting stopped instantly. The one thought in each bee’s mind was to get back to its own hive, and by myriads they flew or crawled home. In a few minutes Bob was able to make his way safely to the little store-hut, where he secured a veil and smoker, though really he now had little need of either. The few bewildered bees drifting about through the smoke were far too frightened to think of stinging.

Peace was restored, though it might be only a temporary one. Bob made haste to contract the entrances of all colonies that he thought might be weak. With a night’s rest and only an inch-and-a-half doorway to defend, he thought they should be able to take care of themselves.

Then he went to examine the cause and beginning of the trouble—the two overturned hives, and he had scarcely glanced at them when he uttered a loud exclamation. There was no doubt at all who had been the disturber here. Long claw-marks ripped the paint of the hives. The combs and frames had been chewed and mangled, showing plenty of tooth-marks on the splintered wood, and a wisp of black hair clung to one of the covers.

“Br’er Bear, and no mistake about it!” muttered Bob.

About half the combs had been chewed up, both the super combs of honey and the lower-story combs of brood. Apparently the bear had liked the taste of unhatched bees. What honey he had left had, of course, been cleaned up by the bees from the yard, and all the scattered wax was now dry as bone. No doubt the raid had been made during the night, and in the morning the neighboring bees had pounced on the spilled and scattered honey and gone mad with robbing.

There was not much that he could do now. He put the hives together again, gathered up the scraps of wax, and also straightened the hive that he had fallen against when the trap caught him. But he was much concerned for the future. It was very probable that the bear would return to this sweet corner, and the trap was very little likely to catch him. In any case, the bees would probably recommence their robbing the next morning. For some time that apiary would need careful attention.

He would have liked to leave his smudges burning so that the odor of the smoke would warn the bear away, but he decided that it would be unsafe. The lakeside slope was littered with all sorts of dry rubbish, and a little fire might easily burn up the entire apiary. Having done all he could, he took his rifle and limped home, rather painfully, for his ankle was very lame.

“How much honey did you find there?” Carl demanded when he entered the cabin.

“I don’t know. I forgot to look,” said Bob. “Only there isn’t so much as there was yesterday, and there’ll be still less if we don’t look sharp.”

“What on earth’s the matter?” cried Alice. “And how did you ever get so badly stung?”

“Robber bees—robber bears—steel traps!” said Bob succinctly; and he proceeded to tell them of the deplorable conditions he had discovered.

“A bear—a real bear this time!” exclaimed his brother. “He’ll be certain to come back to-night for more. I’m going to lay for him. Allie, I’ll get you your bearskin after all.”

“Then I’ll see you do it,” said Alice. “For if you’re going after it to-night I’ll go too.”

“Nonsense! We may be up all night. Bob’ll go with me.”

“Not on your life!” returned Bob, wearily. “I wouldn’t walk back there this evening to save all the bees from destruction. There’s no sense in going to-night anyway. The bear will never come back with that strong smell of smoke in the yard.”

“You can’t tell. I believe he would,” Carl argued. “His mouth will water for honey too hard to resist. Anyhow, I’m going to take a chance on it and wait for him with some buckshot shells.”

“And I’m certainly going!” affirmed Alice. “You don’t want to go alone—and Bob says the bear won’t come, so there’ll be no danger.”

Carl really did not want to spend the night in ambush alone, and as Bob was in no condition for the adventure, he agreed to allow Alice to go with him. There would be a moon that night, but not till after eleven o’clock, and if they were to reach the apiary before dark, it would be necessary to start immediately after supper.

Alice put on a short skirt, a jersey, and a tam-o’Shanter, and took the shotgun, for which Carl carried half a dozen buckshot shells in his pocket. He carried Bob’s rifle himself, and they took a lunch with them, for if the vigil lasted all night, they would be decidedly exhausted before daylight. Bob jeered mildly at the whole proceeding, and after watching them off went immediately to bed.

It was a long tramp through the twilight to the lake apiary, and it was almost dark when they arrived. A faint smell of smoke still lingered in the air from Bob’s smudges, and from the hives arose a dull, uneasy roar. Honey had been won and lost that day, but by no honest means, and all the bees were still suspicious and restless. By morning the fighting would probably recommence.

There was a very faint air blowing from south to north, and Carl and Alice ambushed themselves on the leeward side of the yard. The ground rose slightly there, so that they had a good view of the whole apiary. Clumps of small cedars grew all around them, and a big fallen log in front made an excellent breastwork.

They placed their weapons across the log and sat down, glad of the rest. The evening air was cool, almost frosty, and the wilderness was very still. They barely dared converse, even in the faintest whispers.

For an hour or so they were both on tenterhooks of expectation, but as time passed this wore off, and they began to feel weary and drowsy. Carl would have found more difficulty in keeping awake, only that from time to time his ears caught some rustle or crackle in the underbrush that set him thrilling with excitement. But nothing ever appeared in the bee-yard, where the roaring had gradually quieted.

At last the sky lightened over in the east, and the moon gradually appeared between the trees. It was almost full, and the forest changed marvelously into deep black and pale silver. Voices began to be heard from the wilderness as if this were the dawning of the forest day.

The long trail of a swimming muskrat crossed the surface of the lake. A raccoon cried plaintively behind them, and away at the other end of the water they heard the uncanny, cackling laugh of a loon. There were strange murmurings and stirrings everywhere in the undergrowth, and then, far away to the north, sounded a single long shriek, savage and shrill, that caused a sudden long silence in the woods. Probably it was a lynx on his night’s hunting.

Moonrise put them both wide awake again for a time. But as an hour passed and nothing in particular happened, they grew drowsy once more. Alice frankly put her head on the big log and dozed, but Carl kept awake with determination, scrutinizing the edge of the woods all along the ghostly rows of beehives.

Time passes very slowly in such a vigil, and the moon was getting lower in the sky. Carl was growing very tired of it, and he had nudged Alice awake several times, when it suddenly struck him that something had moved in the woods behind him. He was not sure what he had heard, or whether he had heard anything, but the next instant a black figure passed between him and one of the nearest rows of hives.

Almost breathless, he squeezed Alice’s arm and she looked up, blinking. Carl pointed. The dim figure moved forward, with a stealthy, heavy, noiseless swing, till it came out in the clear moonlight, and they both saw the figure of the bear distinctly.

It stopped and seemed a trifle uneasy, swinging its head and evidently sniffing the air. Then, seeming reassured, it suddenly reared up on its hind legs, and with one sweep of its paw, sent the cover of the nearest hive flying.

They saw the bees boil up like smoke into the bright moonlight. Carl grasped the rifle, and cocked it noiselessly. The bear plunged his nose into the super, and they heard the delicate combs and frames smash under his teeth.

A tearing flash from Carl’s rifle split the shadows. Alice uttered a shriek of excitement. The bear was down, rolling over beside the hive, and apparently done for. Carl dashed out in triumph.

But as he approached the animal it reared up unsteadily, and launched a vicious sweep with its iron-clawed paw. Carl sprang back, threw up the rifle and pulled the trigger. Only a soft snap answered. He had forgotten to throw another shell into the chamber.

As he tried to protect himself, the gun was dashed out of his hand, and he might have been struck down the next instant, but Alice charged up and fired both barrels of the shotgun at a range of two yards. As it appeared afterwards, she missed the bear cleanly with both shots; but the buckshot, clustering like a bullet, blew the nearest beehive almost to pieces.

But the shots turned the animal’s attention, and it wheeled and charged straight through the shotgun smoke. Carl uttered a shout of horror, but Alice had already dodged and was running like a deer across the bee-yard, with the bear hotly in chase.

Carl groped desperately for the rifle that had flown out of his hands, but failed to find it. Bees from the damaged hives seemed to be crawling all over the ground. He gave up the search and rushed wildly after the bear, shouting at the top of his voice to distract its attention. It paid no heed, but at that moment Alice, with most remarkable gymnastic skill, scrambled into a small hemlock just in time.

But a bear can climb trees better than any girl! Carl saw the animal rear up against the trunk and he flung a knotted lump of wood with all his force. It hit the beast on the back. It turned with a fierce snarl, and Carl in his turn had just time to scramble into a tree to escape its charge.

The moment he had done so he was sorry, for now he was sure to be clawed out of the branches; but man has an almost uncontrollable instinct to climb a tree to avoid a danger. The bear did indeed rear up against the trunk, clawing the bark and trying to draw himself up. But he did not actually climb, and it came into Carl’s mind that perhaps his first bullet had so injured the animal as to make him unable to climb.

He looked down at it with the most intense anxiety. It really did seem either unable or unwilling to ascend the tree. It walked about uneasily; then went over to the hemlock where Alice was perched, and finally returned to Carl. After sniffing about the foot of the tree it lay down as if on guard.

Carl’s hopes rose as he looked at it. For some minutes it hardly seemed to stir, though he could not doubt its intense vigilance. Perhaps it was remaining quiet in the hope that he would be tempted to come down.

“Are you all right, Carl? Where is it?” called Alice, in a low tone.

“Lying like a dog at the foot of my tree,” Carl responded. “Are you all right?”

“Fairly comfortable. I’ve got a lot of bees on me, though,” she added.

Carl presently became aware that he had bees on him also. The ground must have been covered with them where the bear had torn the hive open; some had probably flown from the combs and settled on the two apiarists. Carl felt one crawling on his neck; he brushed it off, and a moment later was stung by another that had crept up the inside of his trouser-leg. He seemed to have bees crawling all over him, and no doubt Alice, whose skirts afforded less protection, was in even worse case.

In fact, he could hear her squirming about on her branch, and brushing at her clothing.

“They’re stinging me all over,” she called piteously at last. “There must be more than a million bees on me. I believe I’ll get down and run.”

“Don’t do it!” Carl implored. “Try to stand it for a little while. Maybe the bear’ll go away.”

But in his heart he knew that the bear was not at all likely to go away before daylight, and that was a long time to wait. The annoyance of the bees was growing intolerable. In the semi-darkness they would not take wing; they merely crawled, and when they became entangled, they used their stings. Carl could hear the continual “biz-zz” of insects somewhere out of reach under his clothing, and every few minutes he felt the keen thrust.

“I simply can’t stand this,” groaned Alice, and Carl felt that he had had enough of it too.

“Hold on! Don’t move!” he cried. “I’m going to see if I can’t slip down and get the gun.”

He was perching in a beech tree with long and spreading branches, and he had already observed that one of these lower limbs drooped to less than a man’s height from the earth. Carl began to creep out on this branch, as soundlessly as he could, but despite his care he thought he saw the bear move its head and look at him.

The branch sagged heavily under his weight as he went further out. He was six or eight feet from the trunk, and on the side farthest from the bear, and he hesitated for several seconds. He could see Alice watching him anxiously from her tree.

Finally he made up his mind, swung off, and dropped to earth with the spring of the bough. It swished back with a tremendous crackling of twigs, and Carl bolted headlong for the place where he had lost the rifle.

He had no doubt that the bear was pursuing him. He dodged around a beehive and glanced over his shoulder, but saw nothing of the animal. Striking a match, he bent over the earth and was lucky enough to catch the blue glint of the rifle-barrel almost at once.

With a great feeling of relief he picked it up, tried the action and put in a fresh cartridge. The bear had made no sign, and now Carl assumed the aggressive and marched back toward his tree, holding the rifle ready.

He could see the bear plainly, lying in the shadow of the beech, but it did not stir. A suspicion began to grow in Carl’s mind. Advancing a little nearer, he threw a lump of wood, hitting the prostrate animal fairly, but still it did not move. Carl chuckled to himself, walked closer, inspected the bear cautiously, and ventured to punch it in the side with the rifle-muzzle.

“Come down, Allie!” he called. “It’s all right. He’s dead!”

There was a crackling of twigs as Alice slipped down, and then came to look, astonished and almost unbelieving.

“Dead? What killed it?”

“That first shot of mine must have fatally wounded it. Anyway it’s as dead as a door-nail, and seems to have been dead for some time. I expect we might have come down a lot sooner if we had known.”

“I wish we had,” said Alice. “I think I’m a pincushion of beestings.”

“Well, go and get the bees off you. I’ll light a fire, and then I’ll do the same.”

Alice retired into the shadows and loosened her clothing. Carl built a blaze from light wood, got rid of his own bees by brushing and slapping, and dragged the carcass of the bear up to the firelight. It was a medium-sized animal, with a beautiful, black, glossy pelt, but nearly the whole of one side was soaked and stiffened with blood. There was, also, a large pool of blood where it had been lying. It was plain that Carl’s first bullet had cut an artery somewhere, and the bear had gradually weakened and lain down to die quietly by the tree.

There was something rather pathetic about this ending of the wild animal, Alice thought, when she had come back and had it explained to her.

“Well, you’ll have your bearskin anyway. That’ll partly compensate for the honey we’ve lost through him.”

“Do you know how to skin a bear?” Alice demanded.

“No,” replied her brother, “but I’ve got a knife, and I’m going to try.”

It was then shortly after two o’clock in the morning. They got out their lunch gladly, and ate it by the fire, and then Carl undertook the task of skinning the game. The light was not very good, and he had only a large pocket-knife, so that the operation proved longer and more fatiguing than he had expected.

“I don’t know whether I’m doing this in the orthodox manner,” he said as he wrestled with it. “But anyway I’m getting the hide off all in one piece.”

He finished removing it at last, and rolled it up to be taken home. It would need to be washed free of the blood-stains and combed as well, for there were at least a hundred bees tangled in the fur, where they had died in defense of their homes and honey. The carcass was fat and in fine condition.

“Want some bear steaks, Allie?” Carl demanded.

Alice thought not. The stripped carcass of the bear looked somewhat horribly human.

It was between three and four o’clock by that time, and as the moonlight did not penetrate the woods very well, they determined to wait for dawn before returning. The air was decidedly sharp; the warmth of the fire was welcome. They arranged themselves as comfortably as possible beside it, sat talking for a time, fell silent, dozed, and fell asleep.

They were awakened by a shout. It was broad day, and the east was crimson. By the old roadway Bob was just coming into the bee-yard. He had felt uneasy about them and had started for the lake at dawn, despite his lame foot, bringing a honey-pail full of coffee. At sight of the bear his chagrin was boundless.

“Think what I missed!” he exclaimed. “I’ve been hoping for a chance at a bear all this fall, and I’m laid up at the last moment and Carl kills the bear with my own rifle. Hard luck? I should say so!

“But we certainly ought to take one of this fellow’s hams back with us,” he continued. “They say it’s better than pork, and we’ve no fresh meat except what game we can pick up. Give me that knife.”

It was no easy matter to detach the hind quarter with nothing but a jack-knife, but Bob did manage at last to get it off, though he mangled it badly. It must have weighed twenty-five pounds, and the hide and meat would make heavy enough trophies to carry home.

How to dispose of the rest of the carcass was another problem. They did not want to leave it to putrefy in the apiary; they had no means of digging and did not care to throw it in the lake. Finally Carl discovered a little hollow back in the woods, and they scraped it out somewhat with sticks, put in the bear’s body, covered it with what loose earth they could gather, and piled stones over it.

“I suppose one of us ought to stay here to-day and watch the bees, in case of more robbing,” said Alice, doubtfully.

None of them felt much inclined for this duty. Bob pointed to the sky, where heavy clouds were rolling up already.

“No use. It’ll be raining by noon,” he said. “Rain will keep everything quiet, and if it should clear off sooner, one of us can come out again this afternoon.”

So they heated the pail of coffee at the last coals of the fire, drank it, and started homeward, well burdened with the bearskin, the meat, and the two guns. The sky continued to darken; a few drops fell before they gained the cabin, and by ten o’clock a cold, sharp rain was falling. It looked like the first of the autumnal rains; a fire was welcome in the cabin, and Carl and Alice made up for their hard night by a long nap. There was no danger of the bees fighting that day.

It cleared and turned warmer the next morning, and shortly after noon Carl and Bob walked over to the lake. All was quiet; the bees were flying a little, but were not attempting to rob. Evidently the intermission of that rainy day had caused them to recover from their demoralization.

But they were alarmed to notice that Carl’s fire, imperfectly extinguished, had spread among the dry rubbish on the ground till it had been put out by the rain. If the rain had held off, it might have done a great deal of damage. The beehives, made of dry pine, and full of wax and propolis would burn like so many torches.

“I’m afraid I was careless that time,” said Carl. “But we’ll have to come over here with our axes and clear away all this rubbish.”

“Yes, and cut a regular fire guard around the yard,” Bob agreed. “We can’t take any chances on this outfit, and there are always forest fires up here in the fall.”

Just now the woods were wet, and there was no immediate danger, so they resolved to put off this duty till after extracting. For another week the honey was allowed to remain on the hives. Frost fell on three successive nights, but the days were sunny and warm. The maples crimsoned; the woods became a flare of color. They had dried again too, and when Bob went to Morton to order a team to haul the honey, he came back with the report that the village was smoky, and fires were burning in the woods to the westward.

Extracting the honey was not such a hurried task this time. First they cleared out the home yard; then had the full supers hauled in from the lakeside apiary; they took a whole week in taking off the crop, extracting the honey, and packing it in sixty-pound tins, and shipping cases.

The crop of fireweed honey turned out a little over seven thousand pounds of liquid honey, and eighty dozen sections, nearly all of the “Fancy” grade. Besides, they had about two hundred pounds of honey reserved for their own consumption, and for giving away. A generous amount was allotted to Mr. Farr, and they planned to supply Larue with a rich helping if there was any chance of thereby healing up the feud.

“Well, we’re not making the $1,800 we hoped for,” said Bob. “But we ought to get $700 for this extracted honey, and about $200 for the sections. Counting what we sold before, that comes to over $1,500.”

“Besides, we won’t need to feed an ounce of sugar for winter,” Alice added. “The hives are so heavy now that they feel as if they were nailed down. How we’ll lift them into the winter cases I don’t know.”

“Yes, and they’ve mostly got young queens,” said Carl. “With plenty of food and young queens they’re sure to winter well and make money for us next year. We’ve got over two hundred and ten colonies now. Next year we’ll almost certainly clear a couple of thousand dollars.”

But they did not get so much for this crop of honey as they expected. The fireweed honey was not quite equal in quality to that from the raspberry. They received only nine cents for the extracted honey, and $2.25 a dozen for the sections. That brought them $810, however; beside they got $40 for a hundred pounds of beeswax from the melted-up cappings and bits of comb. The boys voted that $40 to Alice as her fee for doing the uncapping.

There was not much left to be done now, but prepare the bees for winter, but that meant making new winter cases for nearly all the hives at the lakeside apiary. They had already had a load of lumber and a keg of nails taken there, and were waiting till they should have leisure to do the carpenter work.

A few days after shipping the last of the honey, the two boys went over to the lake with their axes, intending to clear the place up as well as possible. When they came within half a mile of the yard they heard the distant, resonant bay of a hound somewhere to the west.

“Some one’s breaking the game laws,” remarked Bob, for the open season for deer was still far off. “Probably it’s one of those fellows from Morton.”

The voice of the hound was coming nearer, and by the time they approached the lake, it sounded so close that they stopped in the underbrush to watch for signs of the hunt.

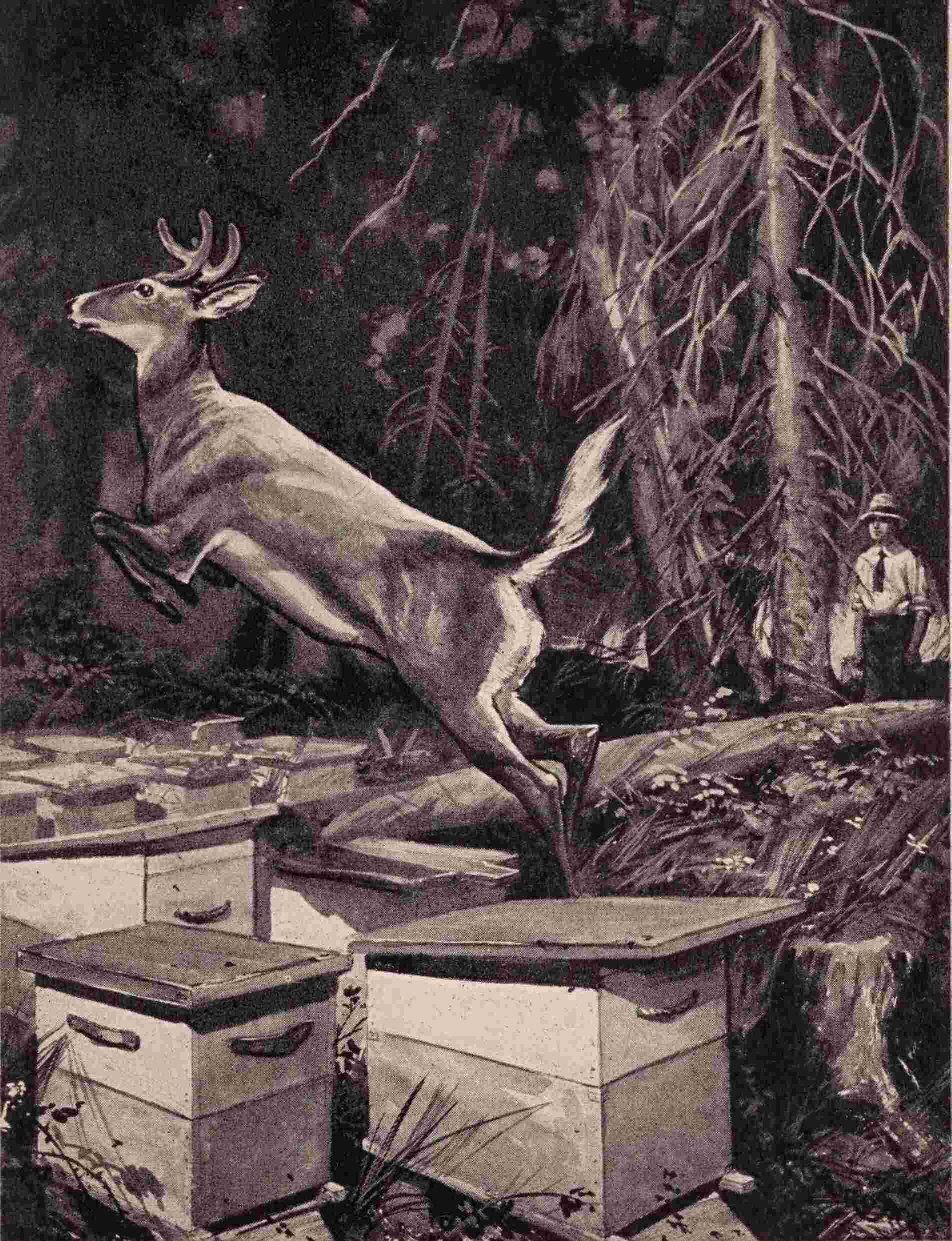

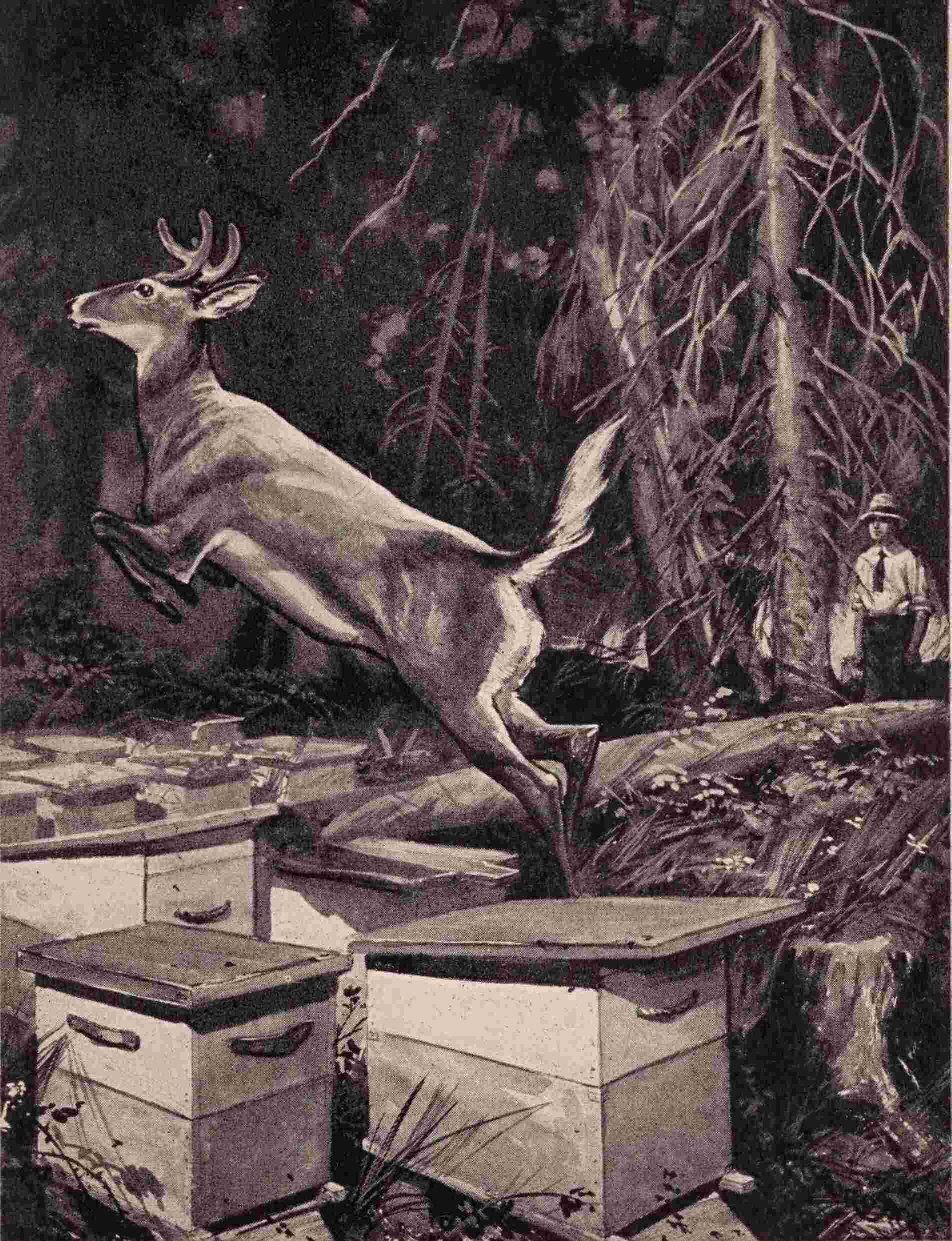

In a few minutes a crash sounded in the woods, and a small buck dashed out and plunged into the shallow water. Instantly a rifle cracked from somewhere down the shore. The deer wheeled, turned straight toward the boys, and had come close before it caught sight of them. It swerved again in a panic and went across the bee-yard, clearing the hives in great bounds.

It wheeled in a panic and went straight over the bee yard, clearing the hives in great bounds

“Crack! crack! crack!” came the reports of the invisible rifle. But the buck, apparently untouched, vanished into the woods. It left a hive with the cover kicked off, and a cloud of angry bees hovering over it.

In another minute the dog came up on the hot trail, yelping and quivering with excitement.

“Why, that’s Larue’s hound,” whispered Carl.

A moment later the squatter himself emerged from the thickets a hundred yards down the shore and came walking slowly up, with his rifle over his shoulder. The dog had been doubling about where the buck had swerved and now, catching the trail, he dashed into the bee-yard with a loud bay, which was followed by a sharp yell. He had blundered right into the hive that the deer had struck, and he was rolling over and over, with brown knots of bees clinging to his hide. Larue ran toward him, but the dog leaped up and bolted into the woods, yelping with pain and fright. He was evidently done with hunting for that day.

The boys squatted down close under the cedars. They heard Larue muttering angrily, and half expected him to shoot up the apiary. But no shot sounded. Perhaps he had grown afraid to meddle with the bees, and after a time they heard him tramp into the woods again.

“Now isn’t that the toughest kind of luck?” Carl muttered. “We’re always running afoul of that fellow. Now I suppose he thinks he has a new grievance against us, though it wasn’t our fault.”

“I don’t see how we dare go away and leave all this bee outfit alone for the winter,” said Bob. “He’d have it all destroyed before spring. We’ve got to make peace with him somehow.”

“Mr. Farr said that he’d never forget a good turn. I’d take a lot of trouble to do him one, if somebody would only show me how!” said Carl.

For some time they discussed methods of placating him. As soon as they felt sure that he had gone a safe distance from the apiary, they set to work to clear up the fire danger.

It was really too great a task for two pairs of hands. They worked most of that day, cleared up a great deal of the brushwood, dragged fallen logs out of the way, and even made some attempt at cutting a fire guard along the shore. But when evening came they seemed to have made little impression.

“We’d best hire a couple of regular woodcutters to clear up the whole place and burn the rubbish,” said Carl. “We can afford it now.”

“Well, we might take another whack at it ourselves, when we come over to make the winter cases,” suggested Bob.

They did not return to the lake for nearly a week, being busy at putting the home hives into their winter boxes again, but the place was constantly and heavily on their consciences. The woods had grown very dry again. No more rain had fallen, and the ground was covered with dead leaves, dry brush, and bark that any spark would set ablaze. Near the cabin there was not so much danger, for the river made a good fire guard on one side, and the woods on the other were mostly of small green spruce and hemlock, which would not burn very readily.

There was fire somewhere certainly. For several days smoke had hung in the west, and the sun had gone down in a sullen haze of red. Almost every day the boys planned to attend to the lake apiary, but some other duty intervened, till, one morning, Alice ran into the cabin with a frightened look on her face.

“There’s smoke in the northwest—toward the lake!” she exclaimed.

Bob and Carl hurried out to look. Smoke was certainly rolling up from the direction of the lake, and there was a light breeze from the north.

“That dry stuff along the shore must have caught somehow!” exclaimed Bob. “What fools we were not to clear it up. But maybe it hasn’t come near the bee-yard yet. Get your ax, quick, Carl—and run!”