CHAPTER II

TROUBLE IN THE DARK

At first they saw nothing of Carl, but as the wagon lumbered up through the stumpy clearing, he came dashing around the cabin with a whoop of delight. He was carrying his shotgun and was accompanied by a fox-terrier, which rushed to the wagon, barking loudly with joy.

“Hurrah!” cried Carl. “I’ve been looking for you all day. Here’s your dog,” he added to the wagoner. “Thanks. He’s been a great help to me.”

“Carl!” Alice screamed. “What in the world is the matter with your face?”

“Haven’t been fighting with Jack, have you?” inquired the driver. “You and him both look as if you’d been up against it.”

Carl grinned rather sheepishly. His face was badly scratched. A long strip of sticking-plaster extended from his ear to his chin, and there was a crisscross of red lines across his cheek. His hands were marked too; one thumb was tied up in a rag, and the white back of the fox-terrier showed half a dozen deep, fresh scratches.

“Oh, nothing,” he said, hastily. “Only skin-deep scratches. Nothing but a bad scare, really. Got our freight all right? Want something to eat?” he added, winking furiously at his brother as a hint to drop the subject of his wounds.

Bob took the hint, nudged Alice, and, though they were both full of curiosity, they said no more, but busied themselves with taking the load off the wagon and hauling the boxes inside the house.

“Oh, what a delightful place!” cried Alice, at the doorway. “And how frightfully dirty!”

“Dirty?” returned Carl, indignantly. “You wouldn’t say that if you’d seen it when I came. The whole place was full of dead leaves and rubbish. The door had stood open all winter, I guess. I’ve been cleaning it out ever since I got here, and I call it in pretty fair shape, considering. Why, the chimney was full of dead leaves and old birds’ nests. There was a family of squirrels living in the roof, and down under the floor there was—well, I’ll tell you later,” he added in a whisper.

“I don’t want to wait,” complained Alice, peering curiously about the place that was to be their home for the next few months.

The building was about twenty feet wide and thirty long, and was divided across the middle by a partition of boards. One of the rooms so formed was evidently the main living-room and kitchen; the other was subdivided into two small bedrooms. Each of these contained, by way of furniture, a rough wooden bunk and a large shelf fastened to the wall, which might serve as a dressing-table.

The large room had a big fireplace of rough stone, with a fire that Carl had lighted still smouldering. The floor was of planks, and at one point stained and splintered, as if by a gun-shot. It had been a rather well-made cabin, and the logs were chinked with lime plaster, but much of the chinking had fallen out, and the cracks yawned wide. There were two windows in the larger room, and one in each of the small ones, with a good deal of their glass remaining. A ladder ascended to a black hole in the ceiling that formed the entrance to a loft under the rafters. Dust and soot were on the log walls, and a decided odor of smoke clung about the whole place.

“Everything is all right now,” Carl assured them. “And the bees are in splendid shape. I’ve been looking at them. Now I know this man wants to start back to Morton as soon as he has rested his horses a little, so as to get home before dark, and I propose that we all have something to eat.”

“Good idea!” said Bob. “I’ll open the box that has our provisions in it.”

“Hold on. I’ve got something better than that!” cried his brother. “Just come with me.” And he led the way around the cabin to an old rain-water barrel that stood beneath a trough from the eaves. It was half full of water, and, as they bent over it, there was a swirl and a flash of orange below the surface.

“Twenty-seven trout!” said Carl. “I caught ’em all in about an hour and a half this morning, and put ’em here to keep alive till you came. One of ’em must weigh four pounds. I tell you, we won’t starve here till the river runs dry.”

“Fried trout and bacon! Splendid!” exclaimed Alice. “Get out about three pounds of those fish, Carl, and clean them. I’ll build up the fire, while Bob gets out the frying-pan and all the eatables he can find.”

In less than an hour they had their first wilderness meal, which their appetites would have made delicious, even if Alice had been a worse cook than she was. The fried trout, rolled in meal, were excellent; so was the bacon and homemade bread; and if there was a shortage of forks and plates, and neither chairs nor table, nobody minded it at all.

As soon as they had finished, the driver started back toward Morton, followed by the fox-terrier. The three apiarists were left alone on their new kingdom, and Alice at once fixed expectant eyes upon Carl.

“Now tell us about it,” she demanded. “What on earth happened to you before we came, and what was the horrible thing you found under the floor of the house?”

Carl smiled in the same uneasy fashion as before, and touched his wounded face tenderly.

“I didn’t want that fellow to hear it,” he explained, “for it’s a queer sort of thing, and very likely he’d have thought it was a lie. It’s rather a joke on me, too, though it didn’t seem funny at the time. I don’t think I was ever so scared in my life.

“We were late in getting off from Morton, and had delays on the way,—one of the tires came off,—so that it was nearly sunset when we got here. It was a chilly, dark evening, and looked like rain. The old shanty was about the dreariest-looking place I ever saw. I’d seen it before, but it looked different in the sunshine. The door was standing open, half-blocked by a great drift of leaves and rubbish. The chimney wouldn’t draw; it was choked with birds’ nests, and, of course, there wasn’t a stick of furniture in the place.

“The driver was in a hurry to start back, for he wanted to get home before midnight, and he helped me to carry my trunk inside, and got ready to go. I didn’t like it; I hadn’t any taste at all for being left there all alone, and I proposed that he leave Jack, the terrier you saw, to keep me company. I knew you would be coming out in a couple of days, and the dog could be sent back.

“So we tied Jack up in the house, and the man went off. I cleared away the leaves so that the door would shut and got in some firewood for the night and poked out the chimney with a pole, so that I could make a fire without being choked with smoke. Then I opened the trunk and got out the grub that I’d brought.

“A bright fire made all the difference in the world, and the house didn’t seem so lonely. Jack was awfully interested in a broken hole in the floor, and I thought a groundhog probably had its den under there. I called him and untied him, and we ate bread and cold ham, sitting on my trunk in front of the fire, and were quite comfortable.

“All my bones were sore with the rough ride out from Morton, and I felt sleepy. It wasn’t long after dark when I made up a pile of dead leaves and old spruce twigs from one of the bunks in the bedroom, and lay down on my blanket. I was tired, but I couldn’t go to sleep. I felt nervous and on the alert. I fancied I heard something moving under the house, and Jack kept startling me by constantly bristling up and growling. I was awfully glad I had him, though, and I was glad I had my gun. I had it standing loaded against the trunk.”

“Goodness! I wouldn’t have spent the night alone in this place, not for—for a million hives of bees,” said Alice, shuddering.

“Well, I don’t know that I would have either, if there had been any chance to get away,” Carl admitted. “But I had to stay, and at last I did go to sleep. I must have slept soundly, too, for I woke in a kind of daze at hearing Jack bark. The fire had almost burned out; there was just a glimmer from the coals. I couldn’t see anything, but off in the corner Jack was barking furiously.

“I thought he had found a rat. I was sleepy and cross and called him to come back. He must have thought I was encouraging him, for I heard him make a rush. There was an awful snarling, and a yowl like a scared cat’s, and a wild rough-and-tumble scrimmage across the floor in the dark. I jumped up, wide awake, you can bet, just as Jack broke away and rushed back to me. He seemed to have been whipped. He was whining and trembling all over.

“Then from the other side of the room I heard a sort of purring growl, exactly like that of a fighting tom-cat, rising into a squall every few bars. I couldn’t see anything, but after a while I made out a pale greenish pair of spots, like eyes.

“I felt pretty sure that it must be a lynx that had strayed into the shanty somehow, and now that the shock was over I wasn’t so much scared. A lynx isn’t very savage, nor very hard to kill, they say. I reached around for the gun, and when I cocked it with a click the beast squalled again. I aimed square between the shining eyes and pulled down.

“The flash half blinded me. The place seemed full of smoke, and Jack charged through it, barking. I heard something rush across the floor, and Jack followed it into the little room.

“I wanted a light badly. I tried to poke up the fire, but it was too nearly out. I lighted a match. The floor was torn up with shot and spattered with blood, just as you see it, but there wasn’t any dead lynx. I got a glimpse of Jack at the door of the bedroom, barking and looking back, and then my match went out.

“I put in another shell and lighted another match. Jack ventured further into the room when I came to the door. I couldn’t see anything, and stepped inside. The match burned out and dropped, and I was feeling for another when something hit me on the shoulder—something alive.

“It was like a small flying tiger. Before I knew it I had got this rip down my cheek, and then two or three more. I felt the soft, cool fur against my neck, and it’s a wonder it didn’t rip my throat open.”

“What on earth was it?” cried Alice, excitedly.

“I didn’t know myself,” returned the narrator. “It was too small for a lynx, but I was fairly cowed by its ferocity. I grabbed it and tried to throw it off. It bit me half through the thumb, but I managed to tear it loose from my coat and fling it down. It mixed up with Jack; there was an awful howling, but I was making for the door.

“I didn’t stop till I was outside, and Jack wasn’t long after me. He’d been beaten again. It was pitch-dark and raining a little, and I cooled down, and the rain washed the blood off my face.

“I thought at first that I wouldn’t go into that house again till daylight, but I gradually got my nerve back. I wanted to find out what sort of beast it was that was living in our cabin. Besides, I didn’t want to spend the rest of the night outdoors in the rain. It wasn’t quite one o’clock. I looked at my watch with a match.”

“You might have gone to the barn,” Bob suggested.

“It never occurred to me. Anyhow, I ventured back to the cabin again. Everything was quiet. I got to the fireplace and made a blaze of dead leaves. It lighted up the whole place, but there was no sort of animal in sight, though I couldn’t see much into the small room.

“So I made up a torch of spruce branches and tiptoed up to the bedroom door again, with my gun ready and the torch in front. Jack charged in ahead of me. I could see well this time. The snarling growl began again, and there on the shelf beside the head of the bunk was a cat.”

“What, a wildcat?” Bob exclaimed.

“Tame wild cat. No, I mean a wild, tame cat. Anyway, it was wild enough for anything. Its fur stood on end all over its body, making it look almost huge. Its ears twitched; its tail snapped; its eyes fairly blazed; and it kept up that singing snarl all the time. It seemed to be paying more attention to the dog than to me, and Jack took precious good care not to come too close.

“At the next glance I saw another cat, a Maltese one, lying dead on the floor. That must have been the one I shot at. Then it struck me that I was up against a whole family, and I looked around for more of them. There was another in a dark corner, with its back arched and its tail puffed like a feather boa. But that one seemed to want to hide more than fight, and I couldn’t see any more.

“I couldn’t help grinning to think how scared I had been by a cat. These brutes must have belonged to the last people who lived here, and they had been running wild ever since. I didn’t want to shoot them. I like cats myself, but not that kind, and I had to get them out of the house for the sake of peace and quiet the rest of the night.”

“I expect the poor wretches were half starved. You might have tamed them, Carl,” Alice suggested.

“I’d like to have seen you calling ‘Kitty, kitty,’ to that snarling young tiger perched on the shelf. No, I threw lumps of wood and bark. When that did no good, I took a loaded shell out of my pocket and threw it as hard as I could. That hit the beast on the back, and it made a leap and lighted square on top of Jack. He had come up too close.

“For a minute all I could see was a tangle of white and gray fur, spinning like a wheel, making every imaginable sort of dog and cat fighting noise. The second cat joined in with its noise, and the uproar was something awful. But Jack was no match for the cat. He broke away with a howl, and rushed behind me.

“The cat jumped after him, blind with rage. I kicked at it, and the beast fastened on my trousers, scratching and biting like a demon. I hit it with the gun-butt, and beat it with the torch. Fire flew in all directions. The cat let go at that, but a lot of dry leaves on the floor caught fire and flashed up, and in a moment the whole place was full of smoke.

“I rushed out again, with Jack in front. At the door I stumbled over something soft that snarled at me. When I was fairly outside I looked back. The small room seemed all on fire, and I began to wonder what Mr. Farr would say if I burned his cabin down on the first night. But the flame was only from light stuff; it didn’t catch on the logs, and in a few minutes the place was dark again.

“I felt pretty certain that the cats were driven out, but I had no idea of going back to see. I knew when I was licked, and I think Jack felt the same way. Then I remembered the barn and I stumbled down there through the beehives. It was a pretty rough place, but it was dry and there weren’t any cats. In the morning I went back to the cabin and cleaned up the mess.”

“Find any more cats there?” Bob inquired.

“Only the dead one.”

“What was it like?”

“Just a big, gray tom-cat. The biggest I ever saw, though. It must have weighed twenty pounds. The fur was badly scorched off, or I think I’d have skinned it.”

“Cats go wild very easily,” Bob remarked. “It’s common enough for a cat to take to the woods. They’re never more than half-tamed animals at the best.”

“It’s no wonder the poor brutes were savage, after living here for a year, and all through the winter too,” said Alice. “If I ever see any more of them I’ll try to tame them.”

“I wish you luck,” said Carl, ironically. “But these cats weren’t poor brutes. They’d been living on the fat of the land. I found the hole through the floor into their den underneath, and I took up a plank. There were gnawed bones of rabbits and partridges there, and all sorts of game. Very likely a litter of kittens had been raised there. If they don’t get killed, there’ll soon be a new breed of wild animal up in these woods.”

“You had an awful time, Carl,” said Bob. “And I’m sure we’re properly grateful to you for clearing out the wild beasts before we came up. But you really ought not to have come here alone. I never thought of danger, but there might have been a lynx or bear in the cabin.”

“Nothing could have been worse than what there was. However, my scratches didn’t go very deep, and I had some sticking-plaster in my trunk. Never mind the cats. Let’s go out and look at the bees.”

“Yes, let’s see them, and then I want to explore the whole place!” exclaimed Alice.

Both the boys had examined the bees before, but this was Alice’s first good look at the apiary, for there had been time for only a hasty glance before dinner. They walked down the rows of hives, through clouds of flying bees that were too busy to be bad-tempered. The hives were arranged in long rows between the house and the barn, facing the southern sun, and there were seven of these rows of great, red, winter cases holding two or three hives each. As far as outside appearances went, the bees appeared to be in good condition. They were flying thickly from the small winter entrance-holes, and coming in by scores with balls of greenish-yellow willow pollen on their legs. This profuse pollen-gathering is always a good sign. It shows that there is a queen in the hive, and a big brood to be fed on this “bee-bread,” and this means a multitude of workers for the still-distant harvest.

Alice lifted the heavy cover of one of the cases. It was packed with sawdust to the height of the enclosed hives, and on the top of each of the two colonies was placed a large, thick cushion of burlap, packed with chaff, to keep the warmth down.

Alice raised the cushion and peeled back the canvas quilt covering the frames. A gush of bees boiled up, taking wing instantly and circling about with an angry “biz-z!” Two or three dashed against the girl’s face, but did not actually sting, for a bee must be driven to absolute frenzy before it makes up its mind to sting and die. But Alice closed the hive hastily, and they all moved on to a more peaceful quarter.

“These bees are blacks and nervous in their temper,” said Carl, laughing. “You can’t handle them like your Italians.”

“We’ll tame them,” Alice returned. “But did you notice the shape that colony was in. It was boiling full of bees from one side to the other. Black or not, it’ll get ten dollars’ worth of honey if there is any bloom in the woods this summer.”

“Oh, lots of them are like that,” Carl assured her. “See how they’re carrying pollen. But we must have a regular overhauling,—open every hive and go through it to see if they have honey enough to carry them through the spring, and what kind of queens they have, and everything. We must keep track of the internal condition of each one.”

“What! The state of every single hive?” exclaimed Bob. “Why, nobody could remember it.”

“If you’re going to be an apiarist, Bob, you must use the right terms,” corrected Alice, laughing. “Colony, not hive. The hive is merely the box that the colony lives in. Oh, yes, a good bee-keeper knows the condition of every colony. It makes it easier to have them all numbered, and then a record can be kept in a note-book. We should do that.”

“Fine training for bad memories, I should think,” Bob remarked. “Now down here in the barn is all the miscellaneous bee-stuff. Let’s have a look at it and see if we’ve got value for our money.”

The barn was some thirty yards from the house. It was also built of logs and was not very much bigger. Although small, however, it was probably large enough to hold any crops that farm ever produced. Part of it was partitioned off, floored with planks, and seemed to have been used as a stable. In this compartment was piled an enormous, disorderly heap of bee-supplies: extracting and comb-honey supers, empty combs and frames, several galvanized honey tanks, an extractor, some worn-out veils, a smoker, and an immense lot of odds and ends.

“I pulled this stuff around considerably when I was looking over it yesterday,” said Carl. “That’s why it’s in such a mess now. Seems to me we got our money’s worth, if quantity counts for anything.”

“A lot of it is probably worthless. Once it was a good working outfit, I suppose,” said Bob, as they contemplated the mass. “But it’ll all have to be overhauled, sorted, and cleaned up. That’ll be work for you when I’m gone.”

“Work for a week, I should think,” said Alice. “But I’ll enjoy it. I expect to find all sorts of surprises in that pile. We’ll come back to it again, anyway, but what we really must do first is to set our house in order. Remember, we haven’t a stick of furniture.”

“Oh, Bob and I can soon knock together some benches and tables,” remarked Carl. “There are some good pine boards here in the barn. We have bunks to sleep in, and we can put up some more shelves, and that’s all we’ll need, for we’ll be outdoors virtually all the time when we aren’t asleep.”

But before attempting to do anything with the house, they explored the rest of their domain, or part of it, for they did not attempt to penetrate far into the woods. The farm was said to contain eighty acres, but not twenty were cleared, and none of it was fenced. In fact, the new tenants never did know exactly where the boundaries of their property were. The forest hemmed them in; as far as they knew, they had no neighbors nearer than Morton, and they could not imagine why the original settler had even chosen that remote and sterile place for a homestead.

“Probably he didn’t know how bad the land was until he cleared it,” Bob suggested.

About twenty yards behind the cabin was the White River, lined with blossoming willows and alders, now full of humming bees. The river was deep and nearly a hundred feet wide. It ran down to Morton and would have afforded an excellent water-route to the village, if they had had a boat.

The settlers had cleared ten acres in front of the house, removed half the stumps, and had apparently tried to grow oats there. Nearer the house was a spot that had been a vegetable garden; a few onions were still sprouting wild. Nearer the house, to Alice’s joy, hollyhocks were coming up, and a bed of hardy ribbon grass persisted.

After this inspection, work commenced in earnest. They built a great fire on the hearth, and Alice filled all the available pots and pans with water to heat. Meanwhile the boys brought up the lumber from the barn, got out their tools, and gave themselves to furniture-making. It was a busy afternoon, and by evening they were all dead tired, but the cabin was transformed.

Alice had swept and scrubbed it and cleaned down the walls and ceiling. The holes in the walls were closed with fresh chinking of clay and moss, and the broken windows partly protected with pieces of board. Carl and Bob had constructed several stout benches, a table that was strong and solid if not beautiful, and had put up shelves on the wall. A brilliant fire of pine-knots flamed in the clean fireplace, and a few gay lithographs decorated the wall. For further decoration, their guns, rods, and saucepans hung beside the chimney.

The small rooms had been cleaned out likewise. The low, board bunks were filled with fresh spruce and balsam twigs, warranted to cure the worst insomnia, and the blankets and pillows were spread over these forest mattresses. A small bench completed the bedroom furniture, for, in true pioneer fashion, they were all to wash in a tin basin on a wooden block outside the door. Here too was the family mirror and comb, but Alice had a small private looking-glass in her room.

The boys promised to construct some kind of pantry or cupboard for the provisions as soon as they had the time, but it was too late to do any more that afternoon. They contemplated the result of their labors with great satisfaction, and really the old cabin looked like a very homelike place. Trout and bacon and eggs were sizzling in the frying-pan; the teakettle hummed, and when the supper was finally spread upon the new plank table they all attacked it with the appetites of true foresters.

They helped Alice to clear away and wash the dishes and built up a blazing fire, for the evening was cool. But they were too tired to sit long before it. Conversation flagged; one by one they nodded, and before nine o’clock Carl announced with a yawn that he had to go to bed.

“No fear of cats to-night, I suppose,” suggested Bob.

“Not a bit,” replied Carl, sleepily. “They can’t get through the door or windows even if they should want to come back, and I closed the way into their den under the house.”

Lighting candles, they retired to their rooms, and Carl, at any rate, was hardly on the sapin bed when he was asleep. It seemed to him that he had slept only a few minutes, though it was really two hours, when he was sharply awakened by a hand on his shoulder. He sat up, startled and dazed, and saw Alice standing beside him with a lighted candle. She looked wide-eyed and frightened.

“Get up, Carl,” she whispered. “There’s something outside, among the beehives. I was so frightened.”

“One of those beastly cats again, I suppose,” said Carl, shaking Bob awake.

“No, nothing like a cat. I couldn’t sleep well. I was nervous, and I thought I heard something stirring outside. I looked out the window, and I saw something dim and big and black—like a bear.”

“A bear!” exclaimed Bob, clutching for his rifle, which he had brought into the bedroom with him.

A few moments later they all sallied into the bee-yard. There was no moon, but the starlight was so brilliant that it was not very dark. The rows of silent beehives looked weird and strange, but nothing stirred among them. They searched the whole clearing in vain. There was no trace of any living thing, and at last they went back to the cabin. It was nearly midnight, and cold, and they built up the fire and warmed themselves.

The boys were sure that Alice had been dreaming, but she was positive that she had both seen and heard some animal, and, in fact, was so nervous that they had difficulty in persuading her to go back to bed again. For some time, indeed, they were all wakeful and alert, but they slept at last. Shortly after daylight they were up again, and the first thing they did was to make another search of the ground among the hives. Sure enough, in a sandy corner of the yard Carl came upon a track. It was not very distinct, but it looked as if a bear might have made it.

“I was sure of it!” cried Alice, triumphantly.

“I believe it is a bear track,” said Bob. “If we’d only got a sight of him last night! But we must look out. A bear in this bee ranch might ruin us in one night. All this honey would seem to him like a gold mine.”

“Or a forest of bee-trees,” added Carl. “Yes, I think we ought to keep a fire burning in the yard every night, even if we have to get up two or three times to make it up. But isn’t it wonderful that this apiary hasn’t been destroyed long ago, if there are bears about?”

The morning air was sharp. No bees were flying till after nine o’clock. It was Friday, and Bob had to go back to Toronto on Monday, so that it was necessary to unpack the bees and go through them all if they were to have his help at this long and heavy task.

They decided to unpack them first, as it would be easier to examine them after they were out of the cumbersome winter cases, and after breakfast the boys began to bring out the wooden, summer hive covers that were stored in the barn with the rest of the supplies. Meanwhile Alice lighted two smokers and got the hats and veils ready. There were canvas gloves that they had brought from home, too, in case the bees should prove especially cross, and with all this apparatus they went out, ready for the first work on the new apiary.

The winter cases usually held two colonies, and were resting on stands of two by four scantling. Alice puffed on the smoker bellows till a strong white cloud poured from the nozzle, and then blew a strong blast into the entrance hole of each of the two hives in the first case. Panic-stricken, the bees rushed inside, and the boys at once dragged the heavy case a few feet out of the way. Lifting the cover, they threw off the cushions, and then lifted the hives out of the cases, setting them down so that the flying bees would find their entrances exactly where they had stood before. For a bee’s homing instinct depends mainly on location. A worker will come back three miles straight to her hive, but if that hive is pushed three feet aside, she may spend hours in trying to find it.

It was hard work. The cases were made of heavy lumber, and the boys had to carry them away and stack them up neatly. Even when the hives were out, the cases, with their sawdust packing, were as much as they cared to handle.

And this juggling with their homes naturally irritated the bees greatly. The summer hives, different in shape and color from the cases that they had been used to, did not look homelike to them. They failed to recognize them. They hung about uncertainly in the air; they tried to enter cases that had not yet been unpacked; and this caused fighting with the guards. Some of them followed the big red cases and tried to enter them again. They grew vicious and stung, so that the apiarists had to put on their gloves. But by degrees a few began to recognize the odor of their old homes, and set up the peculiar whirr that acts as a call to the whole colony. They flocked down on the entrances in clouds, and stood with heads down and wings vibrating fast in the air—fanning, as bee-keepers call it—which is their invariable way of expressing great joy.

Alice left the canvas quilts over the hives, but put on the summer board covers, and then they all went on to the next.

“These hives seem to me awfully light,” said Bob, as he lifted out the box with its bees. “They surely can’t have much honey.”

“I hope we don’t have to feed them,” Alice said, apprehensively. “Never mind; we’ll find out to-morrow. Let’s get them all unpacked to-day.”

Packing and unpacking the hives in fall and spring is the most monotonous and heavy task of the whole season, mere hard, fatiguing work, unrelieved as it is by any interest of skill and science. The young Harmans did not finish the job till nearly dusk, and the boys’ backs and arms ached when they carried the last case away. But the yard looked more like an apiary now, and its owners contemplated it with pride.

The summer hives were sixteen by twenty inches in size, and a little less than a foot deep. They were not painted white, as is usual with bee-hives, but were all sorts of colors, red, green, brown, yellow, giving the apiary a highly cheerful and picturesque effect. Either the former owner had had a lively taste for color, or else he had used whatever paint he happened to have on hand.

That night they kept a fire between the rows of hives, and Bob got up once to replenish it. He heard nothing stir, and in the morning there were no fresh tracks. He predicted that a bear would never again venture so near a dwelling, even with the temptation of unlimited honey.

Both the boys had stiff muscles that morning, but they had planned to inspect the bees thoroughly that day, and determined to go through with it. It promised to be a fine day, and the bees were getting enough honey to make them good-tempered; so they could be handled easily.

“I’m going to show you whether I can’t handle these black bees as painlessly as Italians,” said Alice when they went out, and she stopped before the first hive in the row. She was wearing the usual black-fronted veil, but no gloves, and she pulled her sleeves high up on her wrists.

The colony was a strong one, with scores of bees coming and going. Alice gently blew a little smoke across the entrance, driving in the guards; then she blew a stronger puff. A frightened roar arose within. Panic spread through the hive instantly, for smoke is the only thing that bees fear. Alice waited half a minute and then removed the cover and pulled off the canvas quilt.

A flood of bees surged up between the frames, but she drove them down with a puff of smoke before they could take wing. Another strong puff, and she set down the smoker, and with a screw-driver pried loose the outside frame, next to the hive wall.

It came out hard, for the frames had probably been moved very little for over a year, and the bees had glued them fast. When she lifted it out it was covered with a close layer of black bees, who did not remain quiet on the combs like Italians, but scurried here and there, gathered in clusters, and tumbled off on the ground in knots. They ran over Alice’s bare hands, but were too thoroughly subdued to sting.

The comb was almost wholly filled with brood, sealed over with brown wax in the center, and the younger brood in a circle around this, looking like glistening white worms coiled at the bottom of each cell. In answer to a question from Bob, Carl explained that the egg laid by the queen hatches into a larva in three days. For seven days the rapidly-growing grub is fed incessantly by the bees, and then sealed over with wax to spin its cocoon and undergo its metamorphosis, hatching in eleven days more into a fully-developed bee.

Alice set down the frame, after looking to see that the queen was not upon it, and took out another. This was similarly full of brood, with a narrow rim of honey along the top. All the rest of the ten frames showed much the same condition, except the one next to the other wall of the hive, half of which was filled with fresh pollen, and half with newly gathered honey.

“This colony must be fed,” said Alice, replacing the last frame and closing the hive. “It’s got a splendid force of bees and heaps of brood, but a week of rainy weather would starve it to death. But what do you think of the way I can handle cross bees? I didn’t get a sting.”

“Highly scientific, but too slow,” said Carl. “At your rate we’d be two or three days going through the yard. I think I’ll put on gloves for to-day, so that we can get through them faster.”

In fact, Alice had been obliged to move with the utmost deliberation, stopping frequently to use the smoker afresh, and it was slow work. So Carl put on the sting-proof bee-gloves, with sleeves halfway to the elbow and half the fingers cut off, took the other smoker, and began work on the next row. Bob, who was not skilled at bee manipulation, acted as assistant to both of them, fetching and carrying the things that the two experts needed.

Carl had no need of gloves for the first colony he opened. Instead of a crowded mass of bees, only a little cluster showed between the two center combs. Lifting one of them out, he spied the queen at once, walking over a small patch of brood about three inches in diameter. There were bees enough to cover only one comb well, and they were all huddled in this central space, trying desperately to build up their colony. These were yellow bees, at least half-bred Italians.

“Will they live?” asked Bob, peering into the pathetic little colony.

“Oh, yes, they’ll come on, but probably far too late to do anything at gathering honey this season,” Carl answered. “By the time they’ve built up strong the honey-flow will be over.”

A moment later Alice uttered an exclamation from the hive she had just opened.

“Here’s something wrong!”

Carl and Bob went to look. The colony was of about one-fourth its normal strength, and the bees, instead of being clustered on the combs, were running and scattering in every direction. Despite the smoke they boiled out of the hive, making a peculiar distressful hum, not easily described.

“Queenless, for certain!” Carl exclaimed, recognizing these indications.

And, indeed, when the combs were taken out one by one there was no sign of either eggs or brood. The queen must have perished in the winter. These bees were all old ones from the last season, and they had no possibility of rearing any young. In a little while longer they would all have died, and they were well aware of their desperate state. They were intensely nervous and fierce-tempered, yet their indomitable instinct for work had led them to keep gathering honey. As they had no brood to feed it to, and adult bees eat little, they had accumulated almost two combs full of fresh honey from the willows and maples.

“Unite them with that weak colony I found just now,” Carl proposed.

“Just what I was going to do,” Alice returned.

Carl uncovered the weak colony again, while Bob pried off the bottom from the queenless one. Alice blew a little smoke on both colonies, then Bob carefully lifted the queenless hive and set it on top of the other, making a hive in two stories, with two sets of combs.

At first there was a little disturbance as the bees from the two colonies mixed. Several bees rolled out at the entrance, fighting furiously. Then all was quiet; a contented hum arose within. Lifting a corner of the quilt cautiously, Carl saw the queenless bees standing head downward on their combs, fanning with joy at finding themselves attached to a normal family.

“Now those two together should build up and do something, and neither of them would have been any good alone,” said Alice, with satisfaction.

After these two bad colonies, they came to a long series of good ones, crammed with bees and brood, though nearly all light in honey. Then they found a dead one, with the bees still in clusters on the moldy combs. These contained not a drop of honey; probably the insects had starved. Taking out a comb, Alice pointed out how the bees had crawled deep into the cells, in order to make an unbroken block of heat during the winter, thus making the empty combs almost a solid mass of insects. In very cold weather a strong colony, filling a hive, will crowd itself into a cluster no bigger than a cocoanut.

They worked all that morning, stopped for an hour at noon, and went at it again. By evening they had finished the inspection, and were decidedly disappointed.

Of the one hundred and eighty colonies, ten were dead. Fifteen others were without queens and had to be united at once with normal colonies. From more than twenty hives they had found one or more frames of comb missing. It was impossible to say whether these had been omitted by the former owner, or whether they had been abstracted since. About twenty more colonies were very weak in bees, and would hardly breed up to full strength in time to gather much honey from raspberries. But more than a hundred colonies were strong; some of them indeed were almost overflowing the hive already, and would have to be given more room soon if swarming was to be prevented.

But the worst feature was the shortage of honey. Without an abundance of food in the hive, bees will not rear brood in profusion in the spring, which results in a weakened condition for the harvest. A strong colony needs about twenty pounds of honey to carry it through this critical time, and few had as much as that. Some had only a small patch of fresh willow honey; plainly they were living only from day to day, and much of the brood would perish if a spell of cold or rainy weather should come. To put the bees into strong condition they would have to be fed. It would take nearly a thousand pounds of honey to go around, and this new expense would be a hard strain to bear.

It was hard also to face the fact that their profits would have to come from less than one hundred and fifty colonies instead of one hundred and eighty, though they might have known that some were certain to be dead or queenless.

“It wasn’t really a heavy winter loss,” said Alice, “yet with one thing and another, it does look like a poor chance of clearing eighteen hundred dollars.”

“Lucky if we make a thousand,” answered Carl. “If the season should be a poor one, perhaps nothing at all.”

They were all rather tired and despondent. They had rushed into the enterprise full of enthusiasm, and only now did they begin to realize the obstacles ahead of them.

The next day was Sunday. The weather was still fair, and the bees were still busy in the willows and maples. For some reason, in the peaceful May sunshine, the future looked a little brighter to the Harmans. If the good honey-flow from the willows continued, they might not have to feed after all, or, at any rate, not half so much as they had feared.

There was no necessary work to be done that day, and they were glad of the rest. They watched the bees work in the forenoon; they read and lounged lazily in the sun; and in the afternoon they went for a stroll up the river bank.

The stream was lined everywhere with willows and alders, all in flower and roaring with bees. Trout leaped from the water; once they scared up a pair of wild ducks, that went off with a great splashing and flutter. Several times they saw muskrats navigating along close to the shore, the apex of a long V ripple on the water, and once in a rick of drift logs they caught a glimpse of the slender, graceful form of a mink just diving into a hole.

“I’ll bet there’s lots of fur up here,” said Bob. “I tell you, I believe that if I fail in my exams, or if anything goes wrong, I’ll come up here and stay all winter trapping. I could have got six dollars for the pelt of that mink. It might pay better than keeping bees.”

“Why, I’d like that above all things!” Alice exclaimed. “We’d hunt and snowshoe, and we could skate right down the river to Morton.”

“We could lay in provisions, salt down two or three deer, and hundreds of wild ducks and partridges,” added Carl, with interest.

“Yes, and trout, too. Or perhaps we could catch them through the ice. We could pick and dry raspberries this summer, and I’d make jam—only how would I buy the sugar? Anyhow, we’d have all the honey we could eat, and in the spring we could make maple syrup. I think it would simply be immense. But I’m afraid we’ll have so much money that we won’t have to do it!” she added, with a sigh.

“I wouldn’t be so sure of it,” said Bob. “But by the time I get back I suppose we can tell how the game is going to go.”

Bob had to go back to his classes in the morning, and they spent that evening earnestly discussing the plan of campaign. The bees would have to be left entirely in the care of Carl and Alice till Bob could return, but the heaviest part of the season would probably not come till after that time. They made out a list of some necessary apiary supplies, which Bob was to order in Toronto, and found it hard to order what they needed, without spending more than they could afford. At the same time they prepared an order for half a dozen Italian queens to be mailed by a well-known breeder in the southern states.

“And I’ll buy one good, three-dollar breeding queen,” said Alice. “I won’t be satisfied till I see this whole yard Italianized. The Italian bees are gentler and better workers, and if we ever wanted to sell the outfit again, we would get twice as much for it if it was all thoroughbred stock.”

Early the next morning Bob set out to walk to Morton for the train, and Carl accompanied him to order lumber for making new hives at the local planing-mill. It was late in the afternoon when he returned with the same driver and wagon that had been there several times before, and Jack accompanied them, appearing to have pleasant recollections of the place. Carl brought, besides the lumber, three hundred-pound sacks of sugar, some groceries and provisions, and something else that he threw down at Alice’s feet with a loud clanking of metal.

“What do you think of that?” he exclaimed. “If any midnight marauder gets into that, I think he’ll stay with us.”

It was an enormous bear trap, that Carl had picked up cheap at second-hand. Rusty and savage-looking, it was a formidable affair, with sharp-toothed jaws and double springs that had to be set with the aid of a lever.

“Good gracious! what a cruel, horrible thing!” exclaimed Alice, shrinking back. “Surely you don’t mean to set it? Suppose one of the cats got into it?”

“It would cut him clean in two,” said Carl, hopefully. “But I’m afraid a cat’s weight wouldn’t spring it. Certainly I’m going to set it.”

He did set it that night near the beehives, covering it carefully with leaves, and fastening the six-foot chain to a small tree. Twice during the night he thought he heard the chain rattle, and got up hastily to look, but each time he found the big trap undisturbed.

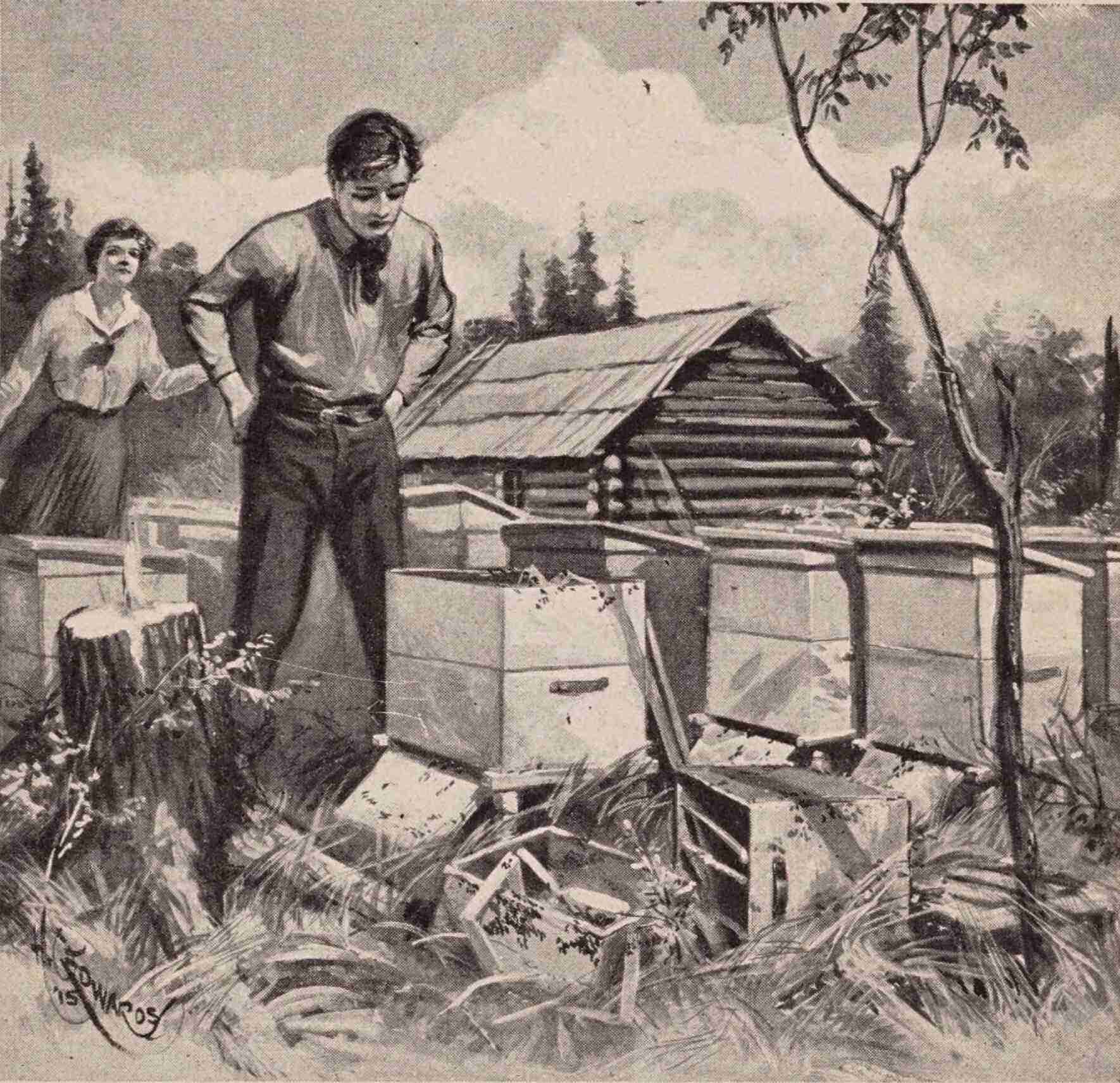

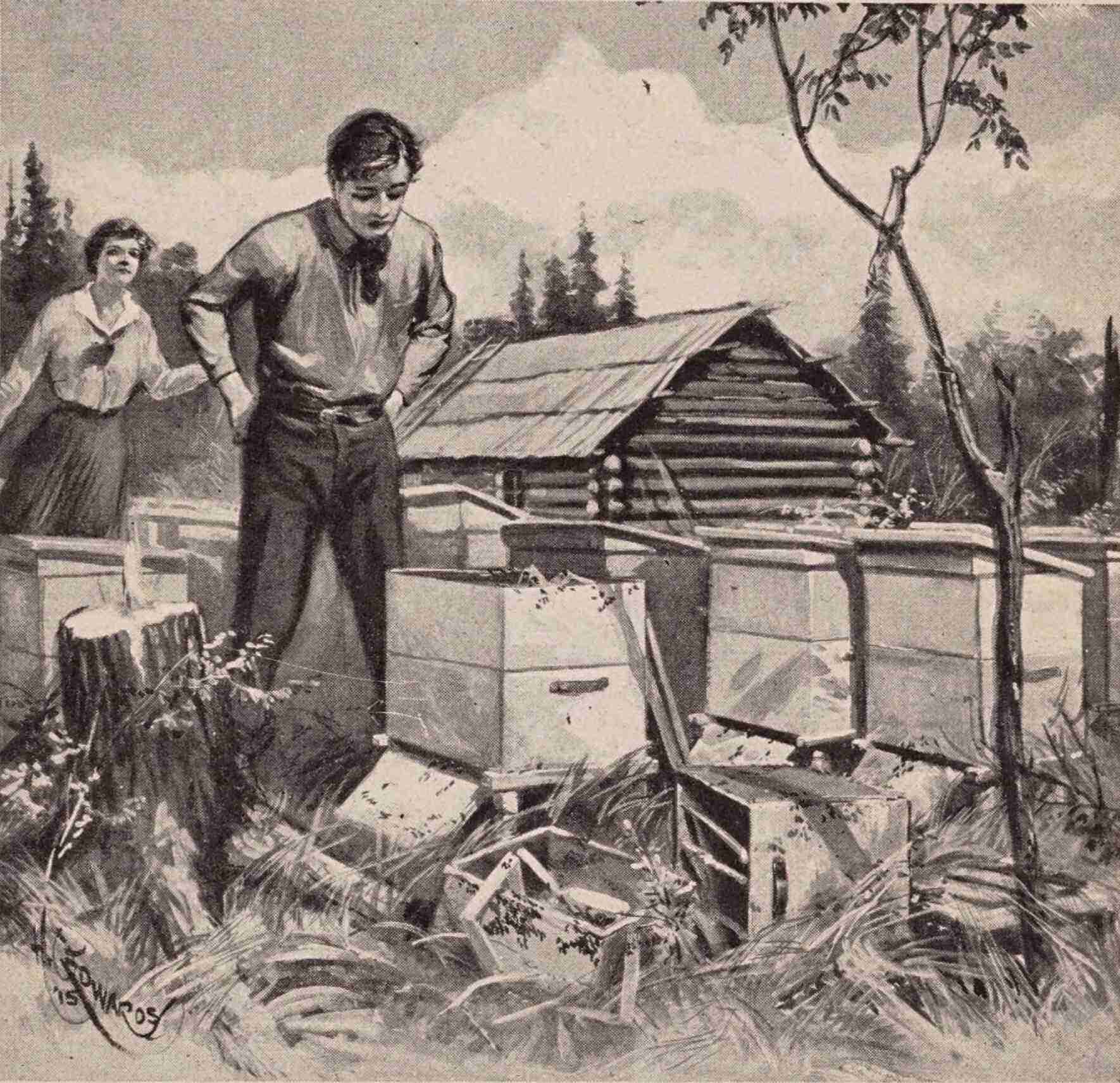

Two of the hives that were farthest from the house had been pillaged

For the next day or two Alice was busy with her work about the cabin. She was making a garden, planting lettuce, radishes, pumpkins, beans, and potatoes with the seeds that she had brought with her. Around the door she planted flowers and carefully nursed the few stalks that still survived there. Carl meanwhile was sorting out the heap of bee-supplies in the barn, and they were both so busy that they had no time to be lonely after Bob’s departure. The bees were still busy, too. The honey-flow from the willows was lasting well, and every day of it meant several dollars’ worth less of sugar to buy for feeding. First of all, every morning Carl went out to look at his trap. For three days it remained unmolested. There was no trace of any animal having crossed the bee-yard, but the fourth morning told a different tale.

Alice was getting breakfast, but she hurried out at her brother’s cry of alarm. The trap was not sprung, but two of the hives, which were farthest from the house, had been pillaged. One of them lay tumbled upon its side, the combs falling loose. The cover had been pulled off the other, and empty frames from which the honeycombs had been broken out littered the ground. Masses of bewildered bees crawled over the wreck, too cowed to be savage.

Alice gave an exclamation of horror at the sight.

“What can have done it?” she cried.

“Don’t know,” said Carl. “But come, let’s put these hives together again. If the queens aren’t killed, they may amount to something yet.”

They set up the hives again, and carefully replaced the frames. For the broken combs they substituted fresh ones from colonies that had died, and while doing this Alice was lucky enough to catch sight of one of the queens sitting on a small stick with a faithful bunch of her bees around her. There was no telling, of course, to which hive she belonged, so they put her in the one that was nearest. The other queen was not to be found, but she might easily have been somewhere among the masses of bees that clung about the wrecked combs.

“Do you think a bear did it?” Alice asked, when they had finished.

“It seems more like a bear’s work than anything else,” answered Carl. “Let’s see if we can find any trail.”

Most of the ground in the bee-yard was too hard and stony to show tracks. Carl began to circle the edge of the clearing to see if he could make out where the animal had entered the apiary.

“Look here, Carl,” Alice suddenly called to him from a distance. “What in the world do you make of this?”

Carl hastened up, and found her bending over a monstrous footprint, the like of which neither of them had ever seen before.