CHAPTER VI

IN WHICH JUAN RODRIQUEZ UNDERGOES AN UNPLEASANT

HALF-HOUR

IN the year 1681 the fickle Guadalquivir still pursued a liberal policy toward Seville and vouchsafed sufficient water to that port to enable sea-going vessels to begin or end their voyages within sight of the Alcazar. Later on, the Spanish sailors were forced, by the treachery of the famous river, to abandon Seville and betake themselves to Cadiz for an ocean harborage.

At the time, however, at which Don Rodrigo de Aquilar fitted out the Concepcion—a high-pooped vessel of ninety tons burden—for his voyage to the silver mines bestowed upon him by Charles II. of Spain, the harbor at Seville enabled the aged diplomat to equip his ship without leaving his library. By giving his orders to his secretary, Juan Rodriquez, who carried them to Gomez Hernandez, captain of the Concepcion, Don Rodrigo was relieved of the friction which in those days frequently soured an adventurer’s disposition even before he had put to sea.

The necessity for haste, lest the veering winds of Doña Julia’s fickle fancy should at the last moment balk her father’s enterprise, had been impressed upon Juan Rodriquez, who needed no hint from Don Rodrigo to make him a gadfly to the captain of the Concepcion. Long before he weighed anchor, Gomez Hernandez had sworn by his favorite saint that if the opportunity ever came to him to put the white-faced, soft-voiced secretary into irons, he would show him no pity. That the perilous voyage before them might furnish him with the means for punishing Juan’s insolence the captain well knew. Let the Concepcion toss the Canaries well astern, and for many weeks Gomez Hernandez would be autocrat in a little kingdom of his own.

Doña Julia’s cabin was, as it were, the hawser which held the clumsy little ship to her moorings. A stuffy room between decks, it seemed cruel to ask a maiden used to the luxury of Seville, Madrid and Paris to spend weeks within its irritating confines. Don Rodrigo had devoted great energy and ingenuity to the task of making his daughter’s quarters aboard ship less repulsive than they had at first seemed. Rugs from the Orient, a hammock made of padded silk, jars of sweetmeats from Turkey, a priceless oil-painting of the Virgin Mary, and other quaintly contrasted offshoots of a fond father’s anxious care combined to make Doña Julia’s cabin a compartment whose luxury was ludicrous and whose discomfort was pathetic.

Had Don Rodrigo de Aquilar better understood the peculiarities of his daughter’s disposition, he would have spent less time in making of her cabin a mediæval curiosity-shop, and would have weighed anchor a week sooner than he did—thus gaining a span of time which would have begotten across the sea a radical difference in the outcome of his expedition. Something of this found its way into the mind of the aged Spaniard after the Concepcion had cleared the mouth of the Guadalquivir and was standing out to sea. Beside him upon the poop-deck stood Julia, her dark eyes gleaming with excitement as they swept the tumbling sea or glanced upward at the bulging sails which drove the awkward craft haltingly across the deep. She had paid little or no attention to the cabin which had taxed Don Rodrigo’s ingenuity, Juan’s patience, and Captain Hernandez’s temper for a month; but the flush in her cheeks and the smile upon her lips, as she watched the waters sweeping the Old World away from her, gladdened her father’s heart as he scanned her changing face.

“The sea is kind to us. See yonder rainbow ’gainst the purple east! An omen such as that is worth a candle to St. Christopher.”

The soft, insistent voice of Juan Rodriquez broke in upon the musings of the grandee and his daughter.

“’Tis not so strange the saints should wish us well,” remarked Don Rodrigo, removing a black velvet cap from his head to let the sea-wind play with his white locks. “We go to serve the work of Mother Church. To tell the heathen of Mary and her Son, to raise the cross where blood-soaked idols stand, to fight the devil with the Book and prayer.”

“And, then—to work the mines,” put in Juan gently.

Doña Julia turned quickly and flashed an angry glance at the soft-tongued secretary. She had noticed, with annoyance, a change in Juan’s manner since the ship had steered for the open sea. In a way that defied explanation in words, the young man had carried himself for the past few hours as if, upon the deck of a ship, he had found himself upon an equality with his master. There was an elusive sarcasm in his words at times, a defiant gleam in his restless eyes, a mocking note in his voice, which the girl noted with an inexplicable feeling of foreboding.

“Aye—to work the mines,” repeated Don Rodrigo, unsuspiciously. “Why not? ’Tis nigh two centuries since treasures from New Spain came over-sea. And for their paltry gold we’ve given them the cross. For every ducat gained by Spain, a soul’s been won for heaven. Harsh measures with the stubborn—these, of course. ’Tis thus the Church must win its way on earth. The fight is not yet done. Upon the border of the lands I own the good Dominicans have built a mission-house. On you, my daughter, will devolve the task to raise a great cathedral where the friars dwell. I’ll dig the silver from the ground for you, and mayhap from my place in paradise the saints will give me eyes to see the glory of your deeds. May Mother Mary will it so!”

The old man’s eyes were upturned in fervor toward the changing glories of the evening sky. The excitement of the embarkation, the enlivening influence of the stiff, salt breeze, and the mysterious promises held out to him by that seductive West toward which his vessel plunged had stirred the blood in the aged Spaniard’s veins, and emphasized at the same moment both his religious enthusiasm and his earthly ambitions.

Doña Julia was on the point of commenting upon her father’s words when there sprang to the deck from below a slender, active man who, ashore, would have looked like a sailor, but aboard ship resembled a soldier. Gomez Hernandez, captain of the Concepcion, was the very incarnation of that dauntless spirit which had, within the lapse of two centuries, carried the arms of Castile and Aragon to the farthest quarters of an astonished globe. Bright, dark eyes, a cruel mouth, a small, agile, muscular frame, and a manner proud or cringing as occasion dictated, combined to make of Gomez Hernandez a typical Spanish seaman of the seventeenth century. Saluting Don Rodrigo de Aquilar respectfully the captain said:

“May I trouble you, señor, to join me in my cabin for a while? I have matters to lay before you which brook no delay.”

Hernandez’s words were addressed to the diplomat, but his piercing eyes rested as he spoke upon the face of Juan Rodriquez. The secretary, even paler than his wont was, gazed across the sea toward the horizon from which the shades of night had begun to creep.

“Await me here, Julia,” said Don Rodrigo, cheerfully, turning to follow the captain to the lower deck. “I will return to you at once. Lead on, my captain. You’ll find I am not mutinous, no matter what you ask.”

In another moment Doña Julia and Juan Rodriquez stood alone upon the poop. The secretary turned from his contemplation of the sea and his restless eyes fell full upon the disturbed face of the girl, a face of marvellous beauty in the half-lights of the fading day. There was silence between them for a time. The creaking of timbers, the complaining of the cordage, the angry splash of the disturbed sea, and from the bow the subdued notes of an evening hymn, sung by devout sailors, reached their ears.

“Señora,” said Juan, moving toward Doña Julia, “I have much to say to you—and there is little time. If my words to you should seem abrupt, the blame lies with my tongue, not with my heart. If that could speak, you’d find me eloquent indeed. I—”

With an imperious gesture, Doña Julia checked his speech. Her symmetrical, somewhat voluptuous, mouth was curved at that moment in a smile of disdain.

“Spare me—and spare yourself, Juan Rodriquez,” she said, coldly, turning her back to the sea and facing squarely the youth, whose eyes met hers with a glance of crafty defiance not unmingled with an admiration that filled her with loathing. “You say more only at your peril. I’ll forgive you your presumption—once. But take good heed of what I say. If you address me in such words again, it shall go hard with you.”

A grayish pallor overspread Juan’s face in the twilight. A cruel smile played across his thin lips, and his hand grasped a railing at his side as if it would crush the stubborn wood.

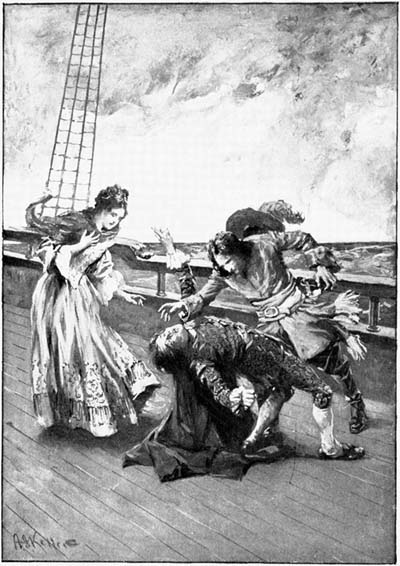

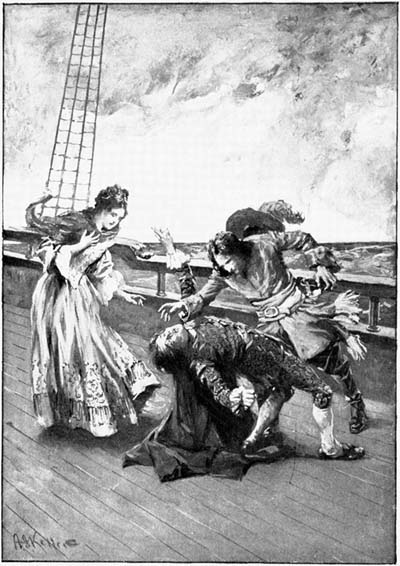

“THE CAPTAIN HURLED HIM DOWN UPON THE DECK”

“You threaten me, Doña Julia de Aquilar,” he murmured, showing his teeth in an evil smile. “You know not what you do. See how our ship is driving toward the murky blackness of the West. Think you I shall be powerless beyond? I say to you, señora, that you, your father, and all you hold most dear, are in the grasp of Juan Rodriquez—your servant in Seville, your master in New Spain.”

He had seized the girl’s wrist and was gazing into her white face with vindictive, hungry eyes. She wrenched her arm free from his repellent grasp, and, drawing herself up to her full height, gazed haughtily at the boastful youth.

“What mad fancies there may be in your mind, Juan Rodriquez, I cannot guess. But this I know: if I should breathe a word of what you’ve said into my father’s ears, you’d lie a prisoner between the decks. And he shall know of this, unless you swear to me to leave me to myself, to speak no word to me, to keep your eyes from off my face, my name from off your lips.”

The threatening smile upon Juan’s mobile face had changed to a spiteful grin while the girl was speaking.

“Your love for Don Rodrigo would be weak, indeed, should you, señora, speak a word of this. I tell you, Doña Julia, your father’s in my grasp. I’ll show him mercy—but I make my terms with you. ’Tis no mad fancy, nor an idle boast,” went on Juan, making a significant gesture toward the slashed velvet upon his breast, “which you have heard from me. I know my power. If you are wise, you’ll take my word for this.”

There was a calm, convincing note in Juan’s voice that froze the rising anger in Doña Julia’s veins. She knew the crafty nature of the man too well to believe that he would thus threaten her unless he had gained possession of some weapon for the working of great mischief. In mute dismay she stood for a moment gazing helplessly at the gray, grim waters which seemed to yawn in hunger for the tossing ship. Suddenly she felt an arm around her waist, and turning quickly found the flushed face of the youth pressed close to hers. An exclamation of mingled disgust, anger, and fear escaped her.

At that instant the strong, nervous hand of Gomez Hernandez seized Juan Rodriquez by the neck. With an ease which his slight figure rendered marvellous, the captain twisted the youth like a plaything in his grasp, and then hurled him, full length, prone upon the deck.

“I crave your pardon, señora,” said Hernandez, with cool politeness, bowing low to Doña Julia, “but Don Rodrigo requests your presence in his cabin.”