CHAPTER XIII

IN WHICH DE SANCERRE RUNS A STUBBORN RACE

IT is but fair to the memory of a noble, if somewhat too impetuous proselyter, to say that if Zenobe Membré—whose achievements and sufferings entitle him to all praise—had realized that martyrdom, the rewards for which he had painted in such glowing colors, really menaced the aroused Mohican, he would have weighed his words with greater care. But the gray friar had long been in the habit of using heroic language to stir the soul of Chatémuc to religious enthusiasm, and he had not, as yet, found cause to regret the use which he had made for years of his pliable convert. Furthermore, the Franciscan placed absolute confidence in the Mohican’s ability to take good care of his red skin. He had seen the craft of Chatémuc overcome appalling odds too many times to long indulge the fear that the Indian’s sudden disappearance at this juncture presaged disaster. Nevertheless, he regretted that his convert had set out upon a mission of some peril with such unwonted precipitancy. The friar would have felt better satisfied with himself if he had been permitted to breathe a word of caution into Chatémuc’s ear before the latter had gone forth upon his lonely crusade against the fires of hell.

“At the worst,” muttered the Franciscan to himself, as he made his way toward the royal litter between lines of black-eyed, smiling sun-worshippers—“at the worst, it would be one life for Paradise and a nation for the Church! May the saints be with my Chatémuc! If he won a martyr’s crown, his blood would quench a fire which Satan keeps alive. But Mother Mary aid him! I love him well! I’d lose my right hand to save my Chatémuc from death! May Christ assail me if so my words were rash!”

Thus communing with himself, the Franciscan approached the excited group surrounding royalty.

“Ma foi, good father, you come to us most opportunely!” cried de Sancerre, springing to his feet, a smile upon his lips but a gleam of repressed anger in his eyes. “Monsieur de Tonti is bent upon repaying his Majesty’s hospitality with marked ingratitude. He orders us—courageous captain that he is—to return at once to Sieur de la Salle. As for me, I have promised the Brother of the Sun to pass the night in yonder city—to the greater glory of our sire, the moon!”

Henri de Tonti, a black frown upon his brow, had overheard the Frenchman’s sarcastic words. Seizing the friar by the arm, he flashed a glance of rage and menace at the exasperating de Sancerre, and drew the Franciscan aside, to lay before him weighty arguments in favor of an immediate retreat to the river.

Meanwhile the younger men among the sun-worshipping nobility, moved by the same cinnamon-flavored inspiration which had driven Chatémuc toward a Satan-lighted fire, had abandoned the scene of the recent feast to indulge in athletic rivalries on the greensward which undulated gently between the outskirts of the forest and the City of the Sun.

“Will you say to his Majesty, señora,” cried de Sancerre, gayly, drawing near to the Great Sun and addressing Noco, “that he has reason to be proud of the prowess of his young men? I have never watched a more exciting wrestling-bout than yonder struggle between those writhing giants. It is inspiring! It is classic! Could Girardon carve a fountain from that Grecian contest over there, ’twould add another marvel to Versailles.”

The Brother of the Sun smiled down upon de Sancerre with warm cordiality as the aged interpreter, having caught the general drift of the Frenchman’s words, turned his praise into her native tongue. The monarch’s momentary annoyance at Henri de Tonti’s lack of tact had passed away, and, standing erect, a right royal figure on his flower-bedecked dais, he watched, with unconcealed pride, the skilful feats with bow-and-arrow performed by the sun-worshipping aristocrats and the prodigies of strength which the wrestlers and stone-hurlers accomplished.

“Tell me, Doña Noco,” exclaimed de Sancerre presently, at the conclusion of a closely-contested foot-race, which even the distraught and restless Katonah, searching vainly with her eyes for Chatémuc, had watched for a moment with bated breath—“tell me the name of yonder greyhound, carved in bronze, who smiles so disdainfully upon the victor. I have never before seen a youth whose legs and shoulders seemed to be so well fashioned by nature to outstrip the wind itself. Why does he not compete?”

The shrivelled crone grinned with delight.

“That is my grandson, Cabanacte,” she answered, proudly. “He’s now a nobleman, for, at the risk of life, he bore the spirit of the sun to us. The whirlwind cannot catch him. The falling-star seems slow behind his feet. He stands, in pride, alone; for none dare challenge him.”

A flush crept into the pale face of the Frenchman as his sparkling eyes garnered with delight all the inspiring features of the scene before him, features which formed at that moment a picture reminding him of the glory of ancient Athens, the splendors of a pagan cult which found in strength and beauty idols worthy of adoring tribute. The passing day breathed a golden blessing upon the City of the Sun, which gleamed in the distance like a dream of Greece in the old, heroic days. De Sancerre, well-read and impressionable, mused for a moment upon the strange likeness of the scene before him to a painting that he had gazed upon, in a land far over-sea, representing Attic athletes engaged in classic games beneath a stately temple behind which the sun had hid its weary face. Awakening from his day-dreams, he turned toward Noco and addressed her in a voice which made his Spanish most impressive.

“Go to Cabanacte, señora, and say to him that Count Louis de Sancerre of Languedoc—the fairest province in the silver moon—dares him to a test of speed, the course to run from here to yonder lonely tree, near to the city’s gate, and back again.”

A grin of mingled admiration and amazement lighted the old hag’s face as she turned toward the King and repeated to him his guest’s daring defiance of a runner whose superiority no sun-worshipper had cared to test for many waning moons. A courteous smile played across the firm, well-cut mouth of the Great Sun as he listened to Noco’s words, but the scornful gleam in his black eyes as they rested upon the Frenchman’s slender, undersized figure was not lost upon the observant challenger. De Sancerre realized fully that he had placed in jeopardy his influence with the Brother of the Sun by risking a trial of speed with a youth whose fleetness he had had, as yet, no means of gauging. If he should be outstripped by Cabanacte the good-will of the Great Sun would be changed to contempt, and the relationship of host to guests, already disturbed by de Tonti’s lack of tact, might be transformed into that of a victor to his captives. What, then, would become of de Sancerre’s efforts to solve the mystery to which old Noco held the key?

But de Sancerre, always self-confident, placed absolute faith in the elasticity of his light, nervous frame, whose muscles had been hardened by his campaigns over-sea and by his wanderings with de la Salle. No fleeter foot than his had been found in the sport-loving army of Turenne, and he had been as much admired in camps for his agility as at courts for his grace. If, perchance, he should outrun the stalwart Cabanacte, de Sancerre felt sure that his easily-won popularity with these impressionable sun-worshippers would be placed upon a much more stable foundation than its present underpinning of smiles and courtly bows.

“My grandson, Cabanacte, sends greeting to the envoy of the moon,” panted Noco, returning speedily to de Sancerre’s side, “and will gladly chase the wind with him in friendly rivalry. He bids me say that night falls quickly when the sun has set and that he craves your presence at this moment on the course.”

Making a courteous obeisance to the Brother of the Sun, de Sancerre was about to hasten to the side of his gigantic adversary, who, stripped almost to nakedness, stood awaiting his challenger, when he felt a detaining hand upon his arm, and, turning petulantly, looked into Katonah’s agitated face.

“Chatémuc! My brother! I cannot see him anywhere!”

“Fear not, ma petite,” exclaimed de Sancerre, cheerily. “Wait here until I’ve made this sun-baked Mercury imagine he’s a snail, and we’ll find your kinsman of the joyous face. ’Twould break my heart to lose the gay and smiling Chatémuc! Adieu! I go to victory, or, perhaps, to death! Pray to Saint Maturin for me, Katonah! He watches over fools!”

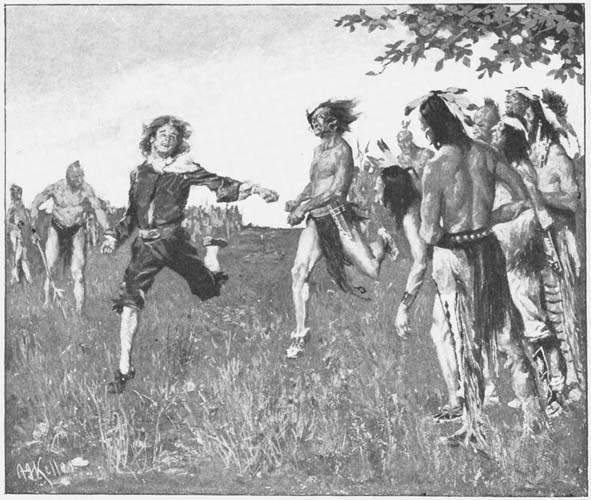

A great shout arose from the sun-worshippers as de Sancerre and Cabanacte, saluting each other with ceremonious respect, stood side by side awaiting the signal for their flight toward the distant tree which marked the turning-point in the course which they were about to run. The Frenchman, attired in tattered velvets and wearing shoes never designed for the use of an athlete, seemed to be at that moment handicapped by both nature and art for the race awaiting him. Almost a pygmy beside the bronze giant, whose limbs would have driven sleep from a sculptor’s couch, de Sancerre had apparently chosen well in asking Katonah for an invocation to the saint who protects fools from the outcome of their folly. The black-eyed sun-worshippers glanced at each other in smiling derision. Surely, these children of the moon must eat at night of some plant or fruit which stirred their blood to madness when they wandered far afield! No dwarf would dare to measure strides with a colossus unless, indeed, he’d lost his wits through midnight revelry in moonlit glades! This white-faced, queerly-dressed, and most presumptuous rival of the mighty Cabanacte might smile and bow and gain the ear of kings, but look upon him now, with head bent forward, waiting for the word! Fragile, petite, thin in the shanks, and with a chest a boy might scorn, he dares to measure strides with a sturdy demigod who towers above him, a giant shadow in the gloaming there!

A howl from the overwrought throng shook the leaves upon the trees. The runners had sprung from the line at a cry and, elbow to elbow, were speeding toward the distant tree. Falling back to Cabanacte’s flank, de Sancerre, seeming to grow taller as he ran, and using his feet with a nimbleness and grace which emphasized the clumsiness of his fleet rival’s tread, hung with ease upon the giant’s pace, moving with a rhythmical smoothness which indicated reserved power. Through the twilight toward the city rushed the courtier and the savage, made equals at that moment by the levelling spirit of a manly sport, while the onlookers stood, eager-eyed and silent, watching with amazement the pertinacity of the lithe Frenchman who so stubbornly kept the pace behind their yet unconquered champion.

As the racers turned the tree marking the half of their swift career, the dusky patriots saw, with growing consternation, that the child of moonbeams still sped gayly along behind the stalwart, wavering figure of a son of suns. The pace set by Cabanacte had been heartrending from the start, for he had cherished the conviction that he would be able to shake off his puny rival long before the turn for home was made. But ever as he strove to increase his lead the bronze-tinted athlete heard, just behind his shoulder, the dainty footfalls of a light-waisted, wiry, bold-hearted antagonist, who panted not in weariness behind the champion after the manner of his rivals of other days. Out of the glowing West came the racers side by side, every step a contest as they struggled toward the goal.

“Cabanacte! Cabanacte!” cried the sun-worshippers, mad with the fear that the dwarf might outrun the giant at the last. For the Frenchman had crept up from behind and was now speeding homeward on even terms with his delirious, reeling, wind-blown, but still unconquered rival. For a hundred yards the racers fought their fight by inches, each marvelling in his aching mind at the stern persistence of his antagonist. Then, when the strain grew greater than human muscles could endure, the bursting heart of de Sancerre seemed to ease its awful pressure upon his chest, his faltering steps regained their light and graceful motion, and, passing Cabanacte as the latter glanced up with eyes bloodshot with longing, the Frenchman, with a gay smile upon his pallid face, rushed past the line, a winner of the race by two full yards.

“THE FRENCHMAN, WITH A GAY SMILE UPON HIS PALLID FACE, RUSHED

PAST THE LINE, A WINNER OF THE RACE BY TWO FULL YARDS”

The hot, generous blood of the sun-worshippers bounded in their veins as they seized the tottering victor and, with shouts of wonder and acclaim, raised him to their shoulders and bore him, a wonder-worker in their eyes, to the smiling presence of their astonished king. But before de Sancerre could receive the congratulations of the Brother of the Sun, the voice of Katonah had reached him over the heads of the excited patricians.

“Monsieur,” cried the Mohican maiden, in French, her voice vibrating with excitement, “Père Membré and Monsieur de Tonti have set out for the camp, and Chatémuc has not returned!”

“Peste, ma petite!” exclaimed de Sancerre, blowing her a kiss over the turmoil of black heads beneath him. “Why trouble me with trifles such as these? See you not that a splinter from a moonbeam has put the sun to shame—to the greater glory of our Mother Church. Laude, Katonah! Laude et jubilate!”