CHAPTER XIX

IN WHICH COHEYOGO EXHIBITS HIS CRAFTINESS

WHILE the Great Sun, by virtue of his divine origin, was technically the high-priest of the nation, it had come about, at the time of Count Louis de Sancerre’s sojourn among the sun-worshippers, that the chief of the holy men, upon whom devolved the duty of keeping alive the sacred fire, had, by the strength of his bigoted personality, usurped all religious authority and had made the temple independent of, and more potent than, the royal cabin. While the chief priest had never openly defied the Great Sun, he had, nevertheless, gradually become the most influential personage in the nation.

It was the advent of Coyocop which had given to Coheyogo, the chief priest, an opportunity for making himself, with no visible break between the church and state, practically omnipotent in the City of the Sun.

Just how thoroughly Coheyogo believed that Julia de Aquilar was the very incarnation of the sun-spirit which, tradition had assured his people, would come to them from the shore of a distant sea, it is impossible to say. It is a fact, however, that from the moment of her arrival among the sun-worshippers the chief priest had openly accepted the maiden as a supernatural guest from whom emanated an authority which he and his fellow-priests were in duty bound to obey. For the furtherance of his own ends and the increase of his own power, the crafty Coheyogo could have taken no better course.

It had come about that Noco as interpreter—the connecting link between the spirit of the sun and the chief priest of the temple—had found herself in a position of great influence. The old hag, a compound of superstition, spitefulness, and saturnine humor done up in a crumpled brown package, had derived malicious satisfaction from playing Coheyogo’s game with a skill and an audacity which had saved her from the many perils which had menaced her in the pursuit of this eccentric pastime.

Coheyogo would visit Coyocop with Noco and lay before the sun-spirit some problem dealing with the attitude of the temple toward a question at that moment interesting the sun-worshippers. The quick-witted and fearless interpreter would answer the chief priest with advice originating in her own fertile brain, and, in this way, would protect Coyocop from cares of state, while she made a willing tool of Coheyogo and satisfied her own love of mischief. Within well-defined limitations, old Noco, at the moment of which we write, held under her control more actual power than either the Great Sun or the chief priest. As the tongue of Coyocop, the court of last resort in a priest-ridden state, the old crone, with little fear of detection, could put into the mouth of the sun-spirit whatever words she chose. Fortunately for Coyocop and the sun-worshippers, the aged linguist was, at heart, progressive rather than reactionary. She had cherished for years a detestation for the bloody sacrifices of the temple, which heterodoxy, had Coheyogo suspected it, would have long ago brought her life to a sudden end. As it was, the old interpreter had made use of Coyocop to mitigate, as far as possible, the horrors which a cruel cult, administered by heartless priests, had inflicted upon a brave, kindly, but too plastic race.

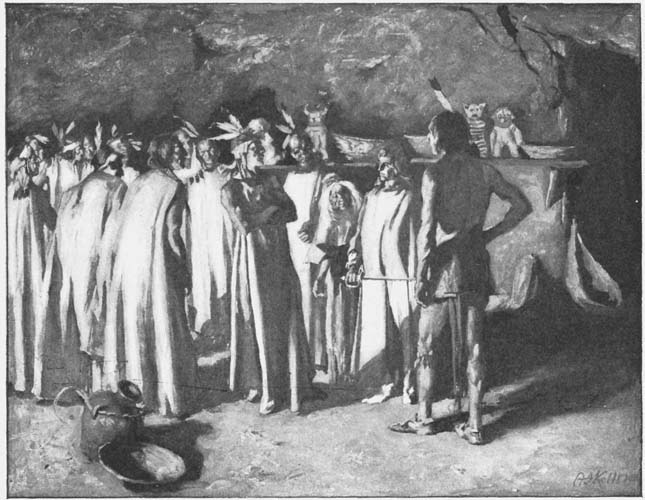

It was now a full hour past high noon, and Coheyogo stood, surrounded by the temple priests, confronting Cabanacte by the sacred fire. The interior of the sun-temple was not less repulsive to an unbiased eye than the skull-crowned palisades outside. Divided into two rooms of unequal size, the interior of the blood-stained fane served the double purpose of a gigantic oven to keep the veins of the living at fever-heat and of a tomb in which the bones of the noble dead might crumble into dust. In the larger of the two rooms, in which the chief priest was now holding a council of the elders, stood an altar seven feet long by two in width and rising to a height of four feet above the floor. Upon this altar rested a long, hand-painted basket in which reposed the remains of the reigning Great Sun’s immediate predecessor.

The heat of the room was intense, for no windows broke the monotony of the temple’s walls; mud-baked partitions, nine inches in thickness. Rows of plaited mats covered the arched ceiling of the interior. At the end of the room furthest from the sacred fire, folding doors, closed at this moment, opened into the private apartments of the chief priest. Running from these doors, along both sides of the smoke-blackened hall, wooden shelves supported the grewsome relics of horrid ceremonials. Long lines of baskets, daubed with red and yellow paint, contained the revered dust of Great Suns gone into the land of spirits accompanied by the loyal souls of their strangled wives and retainers. Scattered between these tawdry urns, the shelves bore crudely-wrought clay figures of men, women, serpents, owls, and eagles; and here and there an offering of fruit, meat, or fish stood ready to satisfy the craving of any uneasy ghost coming back dissatisfied with the cuisine of the spirit-world.

Grouped around the sacred fire, in which logs of oak and walnut preserved a flame which the sun-god had vouchsafed to man in a remote day of grace, the temple priests, whose dark faces bore evidence of their internal agitation, stood listening and watching as Cabanacte and Coheyogo faced each other at this crisis and discussed, in subdued tones, a question of immediate significance. As the chosen discoverer of Coyocop, the instrument employed by the great spirit for the fulfilment of an ancient prophecy, Cabanacte occupied an influential position in the eyes of the temple brotherhood. The inspiration from on high, which had turned the giant’s feet toward a haunted shingle upon which the spirit of the sun lay asleep, might at any moment stir his tongue with words of divine origin. Since the night upon which Cabanacte had brought Coyocop to the City of the Sun, he had always been listened to with rapt attention by the jealous guardians of the sacred fire.

“He threatens me, you say?” muttered Coheyogo angrily, gazing up at Cabanacte with flashing eyes. “And you have told the people that the Great Sun dies because I do not worship this white-faced conjurer who says the moon is his? Beware, oh Cabanacte, what you do! I’ll dare the magic of his silver wand and prove to him the sun-god is omnipotent.”

Drawing himself up to his full height, until he towered a full half-foot above the stately sun-priest, Cabanacte exclaimed, in a low, insistent voice:

“Have you forgotten Coyocop? Did she not last night—old Noco tells the tale—command you to do honor to this white face from the moon? ’Tis you, Coheyogo, who should now take heed. ’Tis not moon-magic which you would defy. ’Tis Coyocop herself, the spirit of the sun, our god.”

The chief priest remained silent for a time, gazing thoughtfully at the sacred fire, which seemed to roar and flash and snap and dance before his restless black eyes as if it threatened him with tortures for harboring a sacrilegious thought. Had not the spirit of the sun itself, through Coyocop’s inspired tongue, commanded him to treat the nation’s white-faced guest with all respect? The great power which Coheyogo had wielded for a year seemed to be slipping from his grasp. Its foundation-stone had been the word of Coyocop. Should he not heed her late behest he’d pull the very underpinning from beneath his tower of strength. Furthermore, the Great Sun, an easy-going monarch, subservient to the chief priest’s stronger will, lay at death’s door. His successor to the throne, his sister’s son, Manatte, was a headstrong, stubborn youth, upon whom the influence of Coheyogo was but slight. Should the chief priest lose at one stroke the countenance of Coyocop and the good-will of the Great Sun, the supremacy of the temple would be destroyed upon the instant, and Coheyogo would find himself hurled from a pinnacle of power to a grovelling attitude among a people chafing under the cruel tyranny of a bloodthirsty priesthood. Turning fretfully from the threatening blaze to glance up again at the steady eyes of Cabanacte, the chief priest said:

“The words of Coyocop come straight from God.” Facing then the expectant priests, he cried sternly: “Go forth, my brothers, and bid the people to disperse at once. Tell them to go to their homes and offer prayers that the Great Sun may be spared to us. Then come to me here, for I have other work for you to do.”

Left alone in the stilling room with Cabanacte, the chief priest went on:

“Direct the moon-man and old Noco to attend me here. If yonder white face has no evil wish, it may be that his magic may save our king from death.”

Cabanacte smiled grimly.

“I know not, Coheyogo,” he remarked, as he turned toward the exit to the temple, “that the envoy from the moon will heed your curt command. But this I do believe, that, if besought, he’d use his greatest power to save our Sun alive. I will return to you at once.”

With these words the dusky giant strode past the hideous, grinning idols of baked clay, and the plaited coffins of the royal dead, and made his way to the great square from which the white-robed priests were driving an awe-struck, moaning people to their homes.

Coheyogo, glancing furtively around the deserted hall in which the spectres of the dead seemed ready to chase the flickering shadows cast by the miraculous fire, bent down and threw a huge log into the mocking flame, as if to quiet for a moment its spiteful, chiding voice. Suddenly behind him he heard the stealthy footfall of a white-robed underling. Turning quickly from the fire, Coheyogo’s piercing eyes rested upon a priest whom he had recently despatched to the Great Sun’s cabin.

“What news?” cried the chief priest, eagerly. “He still lives?”

“Magani! Listen, master! He lives, and, tossing on his bed, mutters strange words beneath his breath. ’Tis a devil that is in him, for he talks of things we cannot see.”

“And his physician?” asked Coheyogo, impatiently.

“He has done his best, but his eyes are wild and he shakes his head in impotence.”

“He’ll shake it in the noose should the Great Sun die,” muttered the chief priest, with cruel emphasis. “What boots his boasted skill if he fails us when we need him most? But, hark! Our brothers have returned.”

Filing into the temple like a procession of white ghosts with charred faces, the priests of the sun grouped themselves in a circle behind their chief, and stood awaiting in silence the outcome of a crisis which might, at its worst, satisfy their ever-present craving for human sacrifices to offer to their god, the innocent and genial orb of day. That the cruel and crafty Coheyogo dreaded the news of the Great Sun’s death more keenly than they, in their love for an inhuman custom, desired it, they had no means of knowing. But they were to learn presently that there was a new force at work in their city with which they had never before been called upon to deal. As they stood there silent, eager-eyed, remorseless, longing for a continuance of the thrilling sport for which the death of Chatémuc had but whetted their appetites, the sound of light, dainty footsteps approaching the entrance to the temple reached their quick ears. Turning toward the doorway at the further end of the hall, Coheyogo and his motionless and noiseless brood gazed upon an approaching figure which, in spite of its lack of size, was most impressive at that fateful moment. De Sancerre had donned a flowing garment of white mulberry bark, which hid his gay velvets from view and fell in graceful lines from his neck to his feet. His head was bare, and his hair, a picturesque mixture of black and gray, emphasized the pleasing contour of his pale, clean-cut face.

With drawn rapier, the symbol of his dreaded moon-magic, the French aristocrat, his eyes fixed upon the chief priest, strode solemnly toward the sacred fire, followed at a distance by Noco and her long-limbed grandson. As he came to a halt in front of Coheyogo, de Sancerre raised the hilt of his sword to his chin and made a graceful, sweeping salute with the weapon. Turning to Noco, who had now reached his side, he said to her:

“Say to the chief priest that I come to him in amity or in defiance, as he may choose. Tell him that the Brother of the Moon makes no idle boasts, but that ’tis safer for the City of the Sun to win his friendship than to arouse his wrath.”

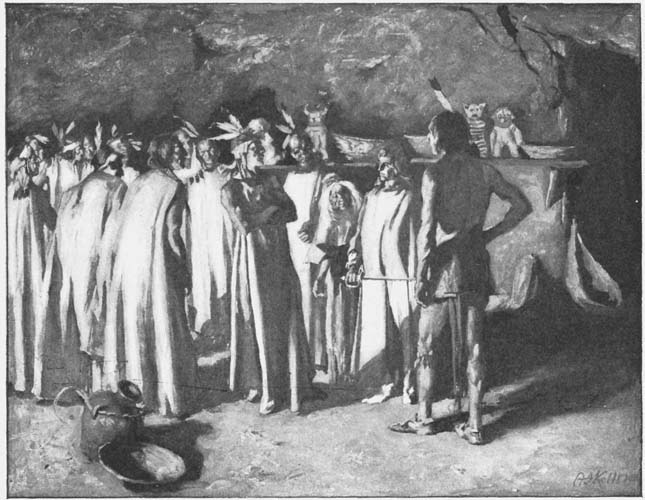

“COOL, MOTIONLESS, WITH UNFLINCHING EYES, THE FRENCHMAN STOOD

WATCHING THE CHIEF PRIEST”

Coheyogo, with a face which none could read, listened attentively to the old crone’s defiant words. His black eyes held the Frenchman’s gaze to his. There was something in the latter’s glance that exercised upon the sun-worshipper a potent fascination, an influence more effective than the impression made upon him by Noco’s speech. The lower type of man succumbed, in spite of his physical superiority, to the will-power of a higher and more complicated intellect than his own. Even had Coheyogo considered it expedient at that moment to wreak summary vengeance upon his white-faced, smiling challenger, it is to be doubted that his tongue could have uttered the words which would have sent de Sancerre to his doom. Cool, motionless, with unflinching eyes and a mouth which wore the outlines of a derisive smile, the undersized Frenchman stood watching the chief priest, outwardly as self-confident as if he had possessed, in reality, the destructive power of which he boasted. Presently Coheyogo turned to Noco, whose wrinkled countenance was twitching with excitement in the fitful glow of the sacred fire.

“The Chief Priest of the Sun has no quarrel with the Brother of the Moon,” said the old hag, addressing de Sancerre a moment later. “But he says to him that the Great Sun, in health and strength at sunrise, now lies tossing in peril of his life. Is it true, he asks, that you have threatened to bring down the same strange sickness upon the temple priests?”

“Not if they do the bidding of Coyocop, the spirit of the sun,” answered de Sancerre, curtly, closely scanning Coheyogo’s face as Noco repeated his words. Then he turned to the interpreter and went on:

“Let the chief priest understand that the spirit of the sun and the spirit of the moon go hand in hand, to the greater glory of the God of gods. Say to him that together Coyocop and I can make a nation great or destroy it at a word. Disobedience to us is impiety to God. If he, Coheyogo, would know this truth, he must be docile, patient, and abide my time. If in his mind the shadow of a doubt remains that what I say is true, let him recall the legends of his race, the promises and prophecies which your fathers told their sons.”

There reigned an ominous silence in the stifling, ill-smelling room for a time, broken only by the malicious crackling of the sacred fire or the impatient grunt of some overwrought priest. Coheyogo, fearing to lose his power by accepting the proffered alliance, but too superstitious to defy the unseen rulers of the universe by rejecting it, stood, grim and self-absorbed, scanning a distressing problem from many points of view. He dared not offend Coyocop, but he resented de Sancerre’s claim to a share in the supernatural authority which the sun-worshippers had attributed to her. After long reflection, the chief priest looked down at the grinning Noco and said:

“Say to the Brother of the Moon that if he has sufficient power to bring down destruction upon this City of the Sun, or even to cast an evil spell upon our king, he is wise enough to cure the latter of the sickness which has laid him low. If he will lead the Great Sun back to us from the very gates of death, he will find within this temple none but servants glad to pay him homage and obey his words. But, if he fails to raise our king, ’twill prove to us he either boasts too much or bears us no good-will.”

De Sancerre’s lips turned a shade lighter, but the mocking smile did not desert them, as Noco translated Coheyogo’s ultimatum into her clumsy Spanish. But even in that moment of supreme dismay, when his life, so he reflected, had been staked against loaded dice, the Frenchman could not refrain from casting a glance of admiration at the crafty priest who had played his game so well. If de Sancerre should undertake the restoration of the Great Sun’s health and should fail to save his life, even Coyocop would be powerless to protect him from the fate which had befallen Chatémuc. He had planned to visit the sick-bed of the King, and to send for Julia de Aquilar to meet him there, should he find that the Great Sun lay afflicted by no contagious disease. But de Sancerre had not foreseen that his boastfulness—which had served him well at times—would place him in his present plight, making his very life dependent upon his skill as a physician. He dared not hesitate, however, to accept the gauntlet thrown down by the keen-witted schemer, whose black eyes were now fixed upon him with a sardonic, defiant gleam.

“It will give me great joy to restore my friend, the ruler of this land, to health,” said de Sancerre calmly to Noco, his gaze still meeting Coheyogo’s unwaveringly. “Will you request the chief priest to accompany me to the royal bedside?”

With these words, the Frenchman turned his back upon the sacred fire and its jealous guardian, and strode haughtily toward the temple’s exit.

“Nom de Dieu,” he muttered to himself, “I know more about the slaying of my fellow-men than how to save them from the jaws of death! I would I could recall the odds and ends of medicine I’ve gathered in my time! But, even then, I fear my skill would not suffice. The Great Sun, if I mistake not, has no more to gain from me than I from him. St. Maturin, be kind to us!”