CHAPTER XXIV

IN WHICH SPIRITS, GOOD AND BAD, BESET A

WILDERNESS

CABANACTE’S wooing of Katonah, an idyl of the forest, a love-poem lost in the wilds, a spring song set to halting words, had filled two simple lives with sadness through days of wandering and nights of melancholy dreams. When the stalwart sun-worshipper had first overtaken the girl, fleeing she knew not whither, and inspired by a motive which she could not analyze, Cabanacte had been greeted by a faint, apathetic smile which had aroused in his heart the hope that, as time went by, her eyes might look into his with the light of a great happiness shining in their depths.

As the days and nights came and went and returned again, while a glad world chanted the wedding-song of spring, and the forest whispered the gossip of the mating-time, Cabanacte’s gentleness brought peace without passion, affection without encouragement, into Katonah’s gaze as it rested upon the dark, strong, kindly face of the dusky youth. Reclining at her feet for hours at a time, the bronze giant would attempt to tell the story of his love to the Mohican maiden in broken Spanish, only a few words of which Katonah understood. But what mattered the tongue in which he spoke? The moon of old corn was at the full, and the universe grew eloquent with a language which every living creature comprehended. The birds were singing in the trees from a libretto which the squirrels and chipmunks knew by heart. The wild flowers blushed at a romance buzzed by bees, and from the grass and the waters and the forest glades arose a myriad of voices repeating the ballad of that gayest of all troubadours, the spring-time of the South.

Cabanacte’s wooing assumed many varying forms. As a huntsman he would lay the trophies of his skill at Katonah’s feet. He would lure a fish from a stream, and, making a fire by rubbing wood against a stone, would serve to her a tempting dish upon a platter made of bark. Wild plums, yellow or red, berries luscious with the essence of the sunshine, and ripe, sweet figs served as seductive foils to the burnt-offerings which he placed upon the altar of his love.

Hand in hand they would wander aimlessly through the flower-scented woods by day, silent for hours at a time and soothed into contentment by a barbaric indifference to what the future might have in store for them. At night Katonah would sleep beneath a sheltering tree, while Cabanacte watched by her side until his eyes grew dim and his head would wobble from the fillips of fatigue. Presently he would shake slumber from his stooping shoulders and sit erect, to gaze down lovingly upon the quiet face and the slender, graceful figure of the melancholy maiden, whose beauty was more potent to his eyes than the heavy hand of sleep. Why should Cabanacte give way to dreams while his gaze could rest upon a vision of the night more grateful to his longing soul than the fairest picture that his fancy had ever drawn?

Now and again the dusky giant would gently touch the sleeping maiden’s brow with trembling fingers, or bend down to press with reverent lips a kiss upon her cool, smooth cheek. Half-awakened by his caress, Katonah would stir restlessly in the arms of mother-earth, and Cabanacte, alarmed and repentant, would draw himself erect again to continue his conflict with the promptings of his love and the call to oblivion with which sleep assailed him.

Often in the heat of noonday his guard would be relieved, and he would slumber beneath the trees while Katonah sat as sentry by his side. Then would the flying and the climbing and the crawling creatures of the forest come forth to sing and chatter and squeak in the effort to lure the silent, sad-eyed maiden to tell to them the secret of her heart. Of whom was she thinking as she reclined against a tree-trunk and gazed, not at the stalwart, picturesque youth stretched in sleep upon the greensward at her side, but up at the white-flecked, May-day sky, a patch of dotted blue above the flowering trees? Why did the tears creep into her dark, gentle eyes at such a time as this? Was she not young and strong and beautiful? Was not all nature joyous with the bounding pulse of spring? What craveth this brown-cheeked maiden which the kindly earth has not bestowed? Surely, the sleeping stripling at her feet is worthy of her maiden heart! Not often does the spring-time lure into the forest, to meet the searching, knowing eyes of a thousand living creatures, a nobler youth than he who, for days and nights, has been her worshipper and slave. The forest is young to-day with vernal ecstasy, but, oh, how old it is with the worldly wisdom of long centuries! What means this futile wooing of a sun-burnt demigod and the cold indifference of a stubborn maiden, who sighs and weeps when all the joys of this glad earth are hers?

The forest holds a mystery, a problem strange and new. The breeze at sunset tells the story to the blushing waters of the lakes, and spreads the gossip through the swamps and glades. The moonbeams steal abroad and verify the tale that the twilight breeze had voiced. A youth and maiden, young and beautiful, so runs the chatter of the woods and streams, wander in sadness along a zigzag trail, and, while he sighs, the maiden weeps and moans. There is no precedent, in all the forest lore, for this strange, futile quest of misery, this daily search for some new cause for tears where all the world is singing hymns of joy and praise.

And all the questions which the forest asked had found an echo in Cabanacte’s soul. Why should Katonah gaze into his loving eyes with a glance which spoke of sorrow at her heart? What was there in all this wondrous paradise of earth which he, a youth of mighty prowess, could not lay at her dear feet? He would take her to the City of the Sun and teach her how to smile in gladness, how to make his home a joy. Did she fear the slavish drudgery of the women of her race and his? Oh, Sun in Heaven, could he but make her understand the broken Spanish of his clumsy tongue, he’d swear an oath to toil for her from year to year, to keep her slender hands at rest and hold her higher than the wives whose fate she feared!

Often would Cabanacte take Katonah’s hand in his, and, smiling up at her as she leaned against a tree, strive to make his scraps of Spanish aid the noble purpose of his heart. Now and then the knowledge which the girl had gained of French would serve Cabanacte’s turn, and she would smile in comprehension of some word which he had voiced. After a time she found herself amused and interested by his earnest efforts to put her into touch with the ardent, uncomplicated longings of his simple soul. One day she had attempted to make answer to his question—clarified by the eloquence of primitive gestures—whether she would return with him to the City of the Sun. They had laughed aloud at the strange linguistic jumble which had ensued, and the spying gossips of the forest had sent forth the stirring rumor that the coy maiden had dried her tears and was at last worthy of the blessings of the spring. But hardly had the forest learned the story of Katonah’s laughter, when the tears gleamed in her eyes and her whispered negative drove the smile from Cabanacte’s face.

From this beginning, however, the youth and maiden had developed, through the long, aimless hours of their sylvan wanderings, a curious, amorphous patois, made up of a few words culled from the French and Spanish tongues and forced by Cabanacte to tell an ancient tale in a language new to man. It brought renewed hope to the youth’s sinking heart to find words which could drive, if only for a moment, the mournful gleam from Katonah’s sad eyes, or, when fate was very kind, tempt a fleeting smile to her trembling lips.

But even after they had garnered a few useful words from Latin roots, there remained a heavy shadow upon the hearts of Katonah and her swain. Between them stood an elusive, intangible, but persistent and domineering, something, which restrained Cabanacte with its cruel grip, and often turned Katonah deaf to her lover’s passionate words and blind to the adoring splendor which shone in his burning eyes. A savage maiden’s foolish dream, a cherished memory which haunted her by day and crept into her sleep at night decreed that Cabanacte should woo her heart in vain and in a forest musical with love should grow sick with longing for the word that she would not speak. With gentle wiles and all the art his simple nature knew he laid before Katonah the treasures of devotion, and, ’though she smiled, and gazed into his eyes with tender gratitude, she waved them all aside and sat in silence in the moonlit night, recalling a pale, clear-cut face upon which she never hoped to look again.

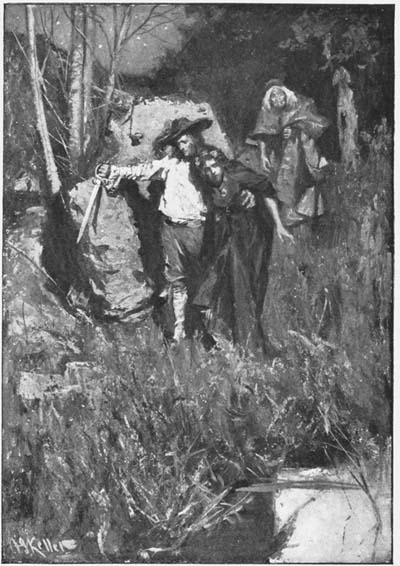

“A WHITE-FACED MAN PRESSING TO HIS BREAST A

DARK-HAIRED MAIDEN”

It was long past midnight, and Cabanacte, weary of his vigil, and worn with the melancholy thoughts which oppressed him, leaned against a tree and dozed for a time while the maiden, reclining at his side, listened in her dreams to a mocking voice which had aforetime been music to her heart. The murmurs of the night had died away to silence as the moon fell toward the west, and the forest had settled itself for a nap before the dawn should hail the noisy day, when Katonah and Cabanacte were hurled to their feet by a crackling crash, which echoed through the protesting woods with a threatening insistence that stopped for an instant the beating of their hearts. Seizing the girl’s cold hand, Cabanacte, glancing around him upon all sides with affrighted eyes, rushed wildly away from the oak-tree beneath which they had found rest, and strove, with a giant’s strength, to win his way to the great river as a refuge from a wilderness in which evil spirits menaced them with ugly cries. Suddenly the stalwart youth paused in his mad career and drew the panting maiden close to his side. Far away between the trees a ghastly creature, a spectral man or monkey, crept and ran and bounded toward the shadow-haunted depths of the forest from which they fled. Knowing all the secrets of the woods, Cabanacte turned cold at the fleeting vision which had checked his wild flight, for never had he seen beneath the moon so weird a sight. Almost before he could regain his breath it had come and gone, and the night was once again his lonely, silent friend.

Trembling from the cumulative horrors which had so suddenly beset their ears and eyes, Cabanacte and Katonah stole through the forest toward the river, which glimmered now and then between the trees. The giant’s arm was thrown around Katonah’s slender waist, and Cabanacte could feel the hurried beating of her aching heart as he pressed her to his side, as if to defend her from some new peril lurking in these treacherous wilds.

Suddenly, as they crept apprehensively toward the outskirts of the trees, the broad expanse of the Mississippi broke upon their sight, and, between their coigne of vantage and the river, they saw a tableau which emphasized their growing conviction that some strange enchantment was working wonders on the earth at night, to bind them together by ties woven in the land of ghosts.

Before their startled gaze stood a slender, white-faced man pressing to his breast a dark-haired maiden clad in black, and as they crouched beneath the underbrush they saw the brother of the moon bend down and kiss the spirit of the sun.

“’Tis Coyocop!” muttered Cabanacte, in a voice of wonder and adoration. “She has come to the forest to drive away the evil demons of the night!”

“Come!” whispered Katonah, urging her lover by the hand toward the woods from which they had just escaped—“come, Cabanacte! I love you! Do you understand my words? I love you, Cabanacte! Come!”

As the dusky giant, a willing captive led back to a joyous prison, followed Katonah toward the haunted glades, he knew that Coyocop had wrought a miracle and had banished from the forest the demons who had warred against his love.