CHAPTER IX

A NICE LITTLE FELLOW

Rodney Merriam and Morris Leighton walked up High Street to the Tippecanoe Club, which occupied a handsome old brick mansion that had been built by one of the Merriams who had afterward lost his money. Merriam usually went there late every afternoon to look over the newspapers, and to talk to the men who dropped in on their way home. He belonged also to the Hamilton, a much larger and gayer club that rose to the height of five stories in the circular plaza about the soldiers’ monument at the heart of the city; but he never went there, for it was noisy and full of politics. Many young men fresh from college belonged to the Tippecanoe, and Merriam liked to talk to them. He was more constant to the club than Morris, though they often went there together.

A number of men were sitting about the fireplace in the lounging-room. The lazily blazing logs furnished the only light.

A chorus of good evenings greeted the two men in unmistakable cordiality, and the best chair in the room was pushed toward Rodney Merriam.

“Mr. Merriam, Captain Pollock; and Mr. Leighton.”

A young man rose and shook hands with the new-comers. Merriam did not know most of the group by name. He had reached the age at which it seems unnecessary to tax the memory with new burdens. It was, he held, good club manners to speak to all the men you meet in a club, whether you know them or not. The youngsters at the Tippecanoe were for the greater part college graduates, just starting out in the world and retaining a jealous hold of their youth through the ties of the club.

“The Arsenal’s got to go. They’re going to sell it and build a post farther out in the country,” announced one of the group. “It’s all settled at Washington to-day.”

“I’m sorry to hear that. It’s another landmark gone,” said Merriam.

“Good for the town, though,” said a voice in the dark.

“Everything that’s unpleasant is,” declared the old gentleman.

Merriam’s tipple had been brought. It was bourbon whisky, off the wood. A keg of it was sent to him by a friend in Louisville every Christmas. As Merriam was occasionally away from town for a year or two at a time the kegs accumulated, so he kept one at the club, and when his order was whisky a bottle was always ready for him. Once when these youngsters had thought to practise deceit by substituting a bottle of the usual club rye for his private tipple, he had detected it by the smell before tasting; for there were a good many things that Rodney Merriam knew, and the difference between Pennsylvania rye and Kentucky bourbon was not the least of them.

“The ordnance people move out in a day or two,” continued the voice in the dark, “and a company of infantry will be here to hold things down until the sale is made. Captain Pollock has been assigned to lay off the lines of the new fort.”

Merriam was holding his glass up to the light in his lean brown fingers. The name of the young man he had been introduced to had touched a chord of memory; and he continued to hold his glass before him so that he could see the clear amber of the liquor in the firelight. He was thinking very steadily and very swiftly. The soft voice of Pollock rose in the shadow almost at his elbow.

“If it isn’t lèse-majesté I’d like to say that I’m sorry the department is making the change. The Arsenal grounds are beautiful. I shouldn’t think the people of Mariona would want to change the place at all, even to get a large post. I envy all the fellows who have had stations here in the past.”

“They have been mighty good fellows,” said Rodney Merriam. “I’ve known most of them—all Civil War veterans, and men we have been glad to know here in town. So Major Congrieve will have to move on! He’s a good fellow and we’ll miss him, but he’s near the retiring age.”

“He’ll retire next year,” said the same voice. It was our southern American voice, soft and well modulated, with the Italian a that the South has preserved inviolate.

Merriam had not drained his glass. He continued to speak, without turning his head.

“Those are hard words, young gentlemen,—retiring age. It’s a polite way of saying shelf. I’m on the shelf myself, and it’s dusty.”

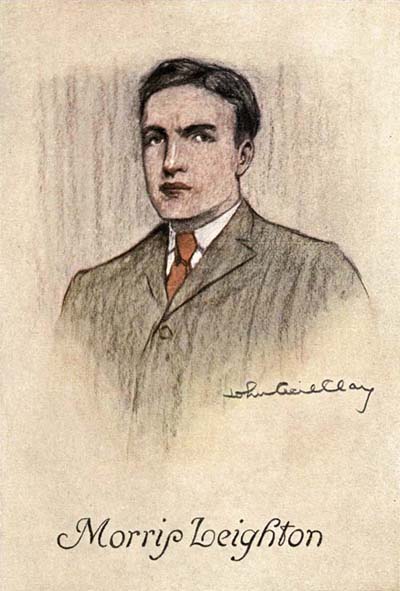

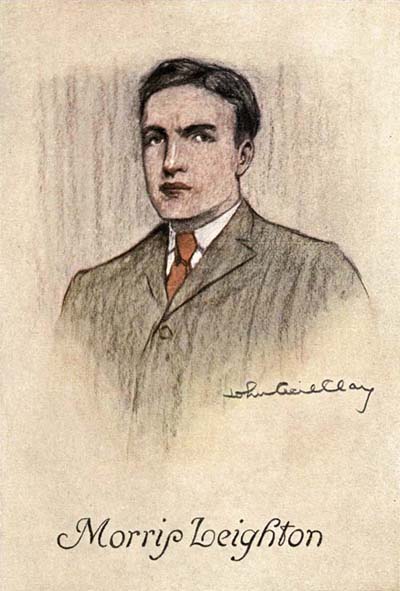

Morris Leighton

“Never!” protested Leighton. “The rest of us are sliding on the banana skins of time—how is that?—right into the grave; while you stand by like the god of youth and mock us.”

Merriam saluted them with his glass and drank it out.

“Captain Pollock has been telling us about the Philippines,” said another one of the group. “We’ve been trying to find out whether he’s an imperialist or how about it, but he won’t tell.”

“That shows his good judgment,” said Merriam.

“It shows that I want to keep my job,” declared Pollock, cheerfully. “And I’ll be cashiered now for certain, if I don’t get back to the Arsenal. Major Congrieve expects me for dinner.”

Baker, who had brought Pollock to the club, shook himself out of his chair and the others rose.

“I’ll see that you find your way back to the reservation,” said Baker.

“That’s very kind of you. And I’m glad to have met you, Mr. Merriam.”

It was the soft voice again, and as they went out into the hall, Merriam looked at the owner of it with interest. He was a slim young fellow, with friendly blue eyes, brown hair, and a slight mustache. His carriage was that of the drilled man. West Point does not give a degree in the usual academic sense; but she writes something upon her graduates that is much more useful for purposes of identification. Frank Pollock had been the shortest man in his class; but his scant inches were all soldierly. The young men with whom he had spent an hour at the Tippecanoe Club had been gathered up by Baker, who had met Pollock somewhere and taken a fancy to him. They all left the club together except Merriam and Leighton, who went to the newspaper room. But Merriam stared at the evening paper without reading it, and when he got up to go presently, he stopped at the club register which lay open on a desk in the hall. He put on his eye-glasses and scanned the page. The ink was fresh on the last signature:

FRANK POLLOCK, U. S. A.

Rodney Merriam then walked toward his own house, tapping the sidewalk abstractedly with his stick.

The next morning he called for his horse early. He kept only one horse, for he never drove; but he rode nearly every day when it was fair. His route was usually out High Street toward the country; but to-day he rode down-town through the monument plaza and then struck east over the asphalt of Jefferson Street, where a handsome old gentleman of sixty, riding a horse that was remembered with pride at Lexington, was not seen every day. Rodney Merriam was thinking deeply this morning, and the sharp rattle of his horse’s hoofs on the hard pavement did not annoy him as it usually did.

Arsenal is a word that suggests direful things, but the Arsenal that had been maintained through many peaceful years at Mariona, until the town in its growth leaped over the government stone walls and extended the urban lines beyond it, was really a pretty park. The residences of the officers and several massive storehouses were, at least, inoffensive to the eye. The native forest trees were aglow with autumn color, and laborers were collecting and carrying away dead leaves.

Merriam brought his horse to a walk as he neared the open gates. A private came out of the little guard-house and returned Merriam’s salute. The man gazed admiringly after the military figure on the thoroughbred, though he had often seen rider and horse before, and he knew that Mr. Merriam was a friend of Major Congrieve, the commandant. The soldier continued to stare after Rodney Merriam, curious to see whether the visitor would bring his hand to his hat as he neared the flag that flapped high overhead. He was not disappointed; Rodney Merriam never failed to salute the colors, even when he was thinking hard; and he was intent upon an idea this morning.

The maid who answered the bell was not sure whether Major Congrieve was at home; he had been packing, she said; but the commandant appeared at once and greeted his caller cordially.

Major Congrieve was a trifle stout, but his gray civilian clothes made the best of a figure that was not what it had been. He was bald, and looked much better in a hat than without it.

“You’ll pardon me for breaking in on your packing. I merely came to register a kick. I don’t seem to know any of the local news any more until it’s stale. I’ve just heard that the Arsenal has been sold and I want to say that it’s an outrage to tear this place to pieces.”

“It is too bad; but I don’t see what you are going to do about it. I’ve already got my walking papers. The incident is closed as far as I am concerned.”

“To give us an active post in exchange for the Arsenal is not to do us a kindness. We’ve got used to you gentlemen of the ordnance. Your repose has been an inspiration to the community.”

“No irony! The town has always been so good to me and mine that we’ve had no chance for repose.”

“But the Spanish War passed over and never touched you. I don’t believe the powers at Washington knew you were here.”

“Oh yes, they did. They wired me every few hours to count the old guns in the storehouse, until I knew every piece of that old scrap iron by heart. If we’d used those old guns in that war, the row with Spain would have been on a more equal basis.”

“I suppose it would,” said Merriam, who was thinking of something else. “But I’m sorry you’re going to leave. We never quite settled that little question about Shiloh; and I’m convinced that you’re wrong about the Fitz-John Porter case.”

“Well, posterity will settle those questions without us. And would you mind walking over to the office with me—”

“Bless me, I must be going! This was an unpardonable hour for a call.”

“Not in the least; only I’ve another caller over there—Pollock, of the quartermaster’s department, who has been sent out to take charge of the new post site. He’s a nice chap; you must know him.”

“I’ll be very glad, some other time,” said Merriam. “Which way does he come from?”

“He’s a southern boy. Father was a Johnny Reb. Another sign that the war is over and the hatchet buried.”

“Pollock, did you say? Tennessee family? I seem to remember the name.”

“I think so. Yes. I’m sure. I looked him up in the register.”

Merriam tapped his riding boot with the whip he had kept in his hand.

“Yes; the war’s over,” he said, “our war. There’s been another since, but it’s preposterous to call that Spanish dress-parade and target practice war.”

The two men went out together, and Major Congrieve twitted Merriam about the thoroughbred’s pedigree.

“I’ll see you again before you go. Luncheon to-morrow at the Tippecanoe Club? That is well. Good morning!”

As Merriam rode out toward the street, Captain Pollock came from one of the storehouses and walked briskly across the grounds in the direction of the office. A curve in the path brought him face to face with Rodney Merriam, who saluted him with his right hand.

“Good morning, Mr. Merriam!” and the young officer lifted his hat.

Captain Pollock’s eyes followed the horseman to the gate.

“I don’t know who you are, Mr. Merriam, or what you do,” he reflected, “but the sight of that horse makes me homesick.”

“He’s a nice little fellow,” Merriam was saying to himself, as he passed the gate and turned toward the city. “He’s a nice little fellow; and so was his father!”

As the thoroughbred bore him rapidly back to town, Rodney Merriam several times repeated to himself abstractedly: “He’s a nice little fellow!”