CHAPTER XIV

AN ATTACK OF SORE THROAT

On the morning of the day set for the Dramatic Club’s most ambitious entertainment, Zelda Dameron lay in bed with blankets piled high about her and a piece of red flannel wrapped ostentatiously around her throat. For the first time since she came home she had failed to appear at the breakfast-table, and Polly climbed to her room and surveyed her critically.

“I’m afraid it’s diphtheria,” said Zelda, hoarsely, putting her hand to the red flannel. “You must telephone to Mrs. Carr right away that I wish to see her immediately. And when she comes bring her right up here.”

“Yes, Miss Zee,” said the black woman, turning away in alarm.

“And Polly,”—Zelda’s face convulsed with pain and she sat up in bed and coughed violently,—“don’t alarm father. Tell him I’m not very sick. And Polly—when Mrs. Carr comes don’t let her fall and break her neck on the stairs. Pull down all the shades and light those candles on the dressing-table.”

She lay back, gathering the collar of a pink bath-robe about her throat.

“Don’t I look awfully sick, Polly? It would be dreadful to die, and me so young. And, Polly,”—she waited for a moment as though in deep thought—“Polly,”—her voice rang out clear, and she waved a hand to the colored woman,—“you may go and telephone Mrs. Carr and then bring me,”—she assumed her hoarse whisper again,—“bring me a cup of coffee, a plate of toast and a jar of marmalade. A doctor, say you, Polly Apollo? Not if I know myself!”—and she hummed in a perfectly natural voice:

“Myself when young did eagerly frequent

Doctor and Saint, and heard great argument

About it and about: but evermore

Came out by the same door where in I went.”

In an hour Mrs. Carr’s station wagon was at the door of the Dameron house. The president of the Dramatic Club heard Polly’s solemn whisper that “Miss Zee was ‘pow’ful sick’” and she ran up the dark narrow stairway with a speed that brought her in undignified breathlessness to Zelda’s room, where the star of the Dramatic Club cast lay coughing. The odor of camphor filled the room, which was not surprising, as Zelda had soaked her handkerchief from a bottle of spirits of camphor only a few moments before and swung it in the air the better to distribute its aroma.

“My dear child, what on earth does this mean?”—and Mrs. Carr rushed upon the bed and peered down on the invalid.

“My throat; it’s perfectly terrible! I must have taken cold at the rehearsal last night.” Zelda sat up in bed, looking very miserable and speaking with difficulty, while she pointed vaguely to a chair.

“This is a calamity,—it’s a positive tragedy.”

“I’m sorry. I’m ever so ashamed of myself. My throat feels like a nutmeg grater.”

“Ugh!” and Mrs. Carr shuddered. “What does the doctor say?”

“Doctor? I wouldn’t have one of them come near me for anything. I had an attack like this once before—in Paris—and I know exactly what to do. I have always kept the prescription the French doctor gave me.”

“But what can we do? You’ve simply got to go through the play to-night, some way.”

“I hope so, I hope so,” said Zelda, in a tone that was without hope.

“Even if you can’t sing, you’ll have to speak the lines. It’s too late now for a postponement.”

“Yes; if my fever goes down, I can speak the lines somehow. I’m afraid there’s fever with the cold.”

“Then you must see the doctor. You must not trifle with yourself.”

“No, no: I beg of you, no! I don’t know any doctor here and a stranger would only be a nuisance. I’ll be better. I don’t like being a trouble; and I’ll come anyhow, dead or alive.”

“That’s the right spirit; you’ve simply got to appear. We’d never hear the last of it if we failed.”

“Yes, I know. Would you mind drawing that shade a trifle lower? That’s better.”

Zelda opened her eyes wide and stared about her dejectedly.

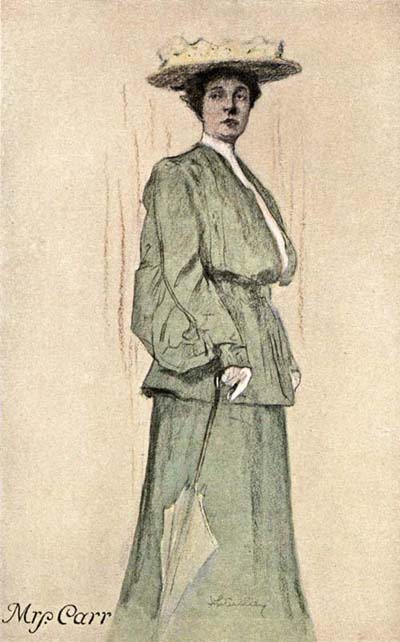

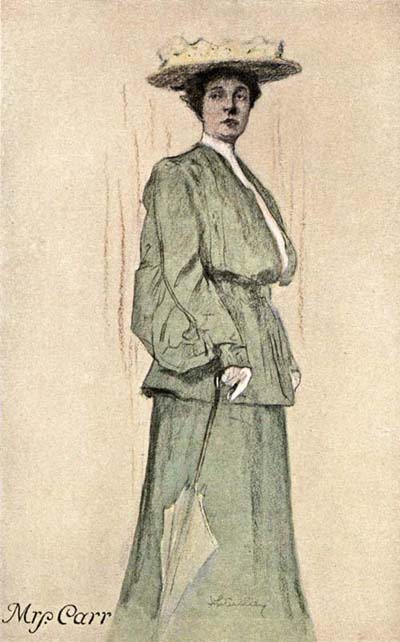

Mrs. Carr

“I’ll tell you what I might do. Something’s just occurred to me. You know Christine’s part is much lighter than Gretchen’s. If Olive would consent to trade with me,—” She broke into a fit of violent coughing. “My! I wish my chest didn’t hurt so. What was I saying? Oh, yes! about that other part,—if Olive would exchange with me, I think I might carry Christine’s part through. She can sing Gretchen as well as I can—”

“Certainly not; it’s impossible. And hers is a soprano part, anyhow.”

“Oh, that’s easy,”—another fit of coughing—“the range is not so very different. That won’t be any trouble.”

“It would take days to do it!” said Mrs. Carr, with a groan.

Zelda lay back on the pillows and pressed the camphor-soaked handkerchief to her nose.

“That’s the only way out of it that I see. If Olive will trade with me, I think I can go ahead; but I can’t do the work of my own part. Gretchen is on the stage all the time. You’d better telephone Professor Schmidt at once. He can have a rehearsal with Olive; but you’d better go to see her. She’s at home to-day,—the Thanksgiving vacation has begun. If she’ll do it—and you tell her she must—I’ll try to take her part.”

“But it can’t be done,—so suddenly,—the change will throw all the rest out.”

Mrs. Carr threw up her hands helplessly.

“Please don’t make me feel any worse,” begged Zelda, piteously. “I’m ever so sorry on your account. And I’ll do the best I can,—honestly I will. And do find Olive and tell her to come over and see me. Tell her to bring her Christine dresses with her. We’ll have to trade costumes and make them suit.”

Mrs. Carr rose as one who will not bow to circumstances.

“For heaven’s sake, don’t fail me! I shall be utterly ruined if we don’t make this go some way.”

“I know,—I know,—I shall certainly be on hand, if they have to bring me in a box,”—and Zelda sighed and coughed again as though her dissolution were imminent.

Mrs. Carr brought Olive back and dropped her at the Dameron door with solemn injunctions to be sure that Zelda was produced at the Athenæum at seven o’clock; then she went with her troubles to Professor Schmidt.

Olive appeared at Zelda’s door bearing a suit-case in her hand. A groan greeted her, as she paused in the doorway, blinking in the dim light of the room.

“Oh, Zee!”

Another moan, followed by a racking cough, and Zelda’s arms beat the covers as though in an agony of pain.

“Olive, have you come? I thought you would never get here!” and Zelda moaned. “Here I am all alone in the house and nobody to do anything for me. I didn’t think you would treat me that way,—and your own flesh and blood, too.”

Olive dropped the suit-case and drew near the bed.

“I’m burning with fever,” moaned Zelda. “It’s typhoid pneumonia, I’m sure. I read of it in the papers. Maybe it’s contagious. Most likely they will put a red sign on the front door so no one can get in.”

She extended her hand to Olive, who took it solicitously.

“You poor dear! When did you first feel it coming on?”

“Oh, I haven’t been well for several days, but I tried to bear up. I’m so miserable I don’t know what to do.”

“Mrs. Carr didn’t think you were so sick. She said you wouldn’t have a doctor.”

“No, I’m afraid of them. Hand me that bottle—can you find it?—on the table there. I can’t bear to face the light. That’s it, I think. Yes, that will do, thank you. Please look at those candles. I’m sure they’re dripping all over everything.”

She took the bottle which Olive handed her, clutching it nervously as though her hope of life lay in it.

Olive had thrown off her coat and hat.

“Sit down, Olive, will you? If you are cold you’d better stand over the register. I’m simply burning up myself.” Zelda succumbed to a fit of coughing. “Have you the music, and the Christine dress? I hate awfully to disappoint Mrs. Carr, and I told her I thought I might carry your part. It isn’t so heavy as Gretchen’s. She’s going to arrange with Herr Schmidt. You’ll have to sing my part. It will do just as well for a soprano. The soprano is always the star, anyhow. You know that as well as I do,” she added petulantly, as though the subject were one of long contention between them.

“It’s horrible. It’s perfectly ghastly,” declared Olive. “I can’t sing it. I can’t sing, anyhow; and this whole show rests on you. You simply must sing your part! About all I had hoped to do was to skip around and do the light fantastic soubrette business like a little goose. To think of my attempting to sing Gretchen,—”

Olive spoke with a fierce animation as the enormity of the proposed change slowly dawned upon her.

“You can do it as well as I can—better! I’d be a perfect wooden Indian as Gretchen. I have almost as much animation as an iron hitching post. It’s either that or I won’t appear at all, and they can go to the North Pole for all me. I’m merely proposing the change as a favor to Mrs. Carr. Your liking it doesn’t matter. You’ve got to like it.”

“But the words,—I might hum the airs,—but I don’t know the words of your part.”

“Nor I yours; but they will come to you. You’ll have a chance to rehearse the part. My sewing things are on the table. We’ll fix up the duds first. About three inches off my first act skirt and a little out of the back and you’ll have it. Do you see the sewing basket anywhere?”

“The whole idea is preposterous. My things can’t be made to fit you,” said Olive, opening the suit-case.

“We needn’t fix those things of yours for me after all,” declared Zelda, suddenly. “I bought a Tyrolese peasant costume once on a time, and here’s my chance to use it. It’s the ideal thing for Christine.”

“But Zee—” began Olive.

“Please don’t make me talk. It’s unkind. I’ll need all my strength for to-night,”—and Zelda lay back and watched her cousin with languid interest. Olive kept up a fire of protest as she set herself to the task of changing the Gretchen costume. She had been taken aback by the suddenness of Zelda’s attack and the necessity for prompt action.

Olive looked up suddenly, holding Gretchen’s gown in one hand and a pair of scissors in the other.

“This is all absurd, Zee Dameron. You can’t put me off as you did Mrs. Carr. I’m going to telephone for the doctor at once.”

“No, no, no! I tell you I have plenty of medicine. I’ll not let a doctor cross the threshold.”

She held up the bottle that Olive had handed her.

“It’s a French doctor’s prescription for just this trouble. It’s fine. I’ve taken quarts of it.”

Olive went to the bed, snatched the bottle and held it to her nose.

“Violet water! A French medicine! You fraud, you awful, shameless fraud!”

“Please don’t abuse me! My chest, oh-h-h!”

“Zelda Dameron, you are no more sick than I am! No person could get as sick as you are pretending to be in a few hours. You were as well as anybody at midnight, and you went through the rehearsal splendidly. Don’t try any tricks on me—”

Zelda sat up again and folded her arms. A smile twitched the corners of her mouth; then she began to speak and fell into another fit of coughing, burying her face in the blankets and seeming unable to recover herself.

“Oh-h-h! it has got me again!” and she shook first with the vigor of her cough and then with laughter. Olive seized her and forced her back on the pillows.

“I’m going away! I’m going home! I don’t intend to have you make a guy of me in such a way as this.” Olive seemed about to cry, and Zelda laughed until the tears rolled down her cheeks.

“I must say that your hilarity is decidedly unbecoming,” said Olive, with dignity. “Mrs. Carr may forgive you, but I never shall,—never!”

Zelda’s mirth rose again at the mention of Mrs. Carr.

“Theodosia would certainly be consumed with rage. Oh, me!”

She sat up in bed and wiped the tears from her eyes. “Please get me a handkerchief from that bureau,—top drawer on your right. This thing smells vilely of camphor. And please don’t take your doll rags and go home. I’m going to be good. Honestly; I’ll be all right in a minute.”

Olive did as Zelda bade her, and returned to the bedside of the invalid with unrelenting condemnation.

“Please don’t look at me that way, Olive. I didn’t mean to laugh; but it is funny. And when you look so hurt and dignified I can’t help it. But we’ve traded parts, anyhow. Don’t say a word. I have reasons,—of state, as they say in romantic drama,—and nothing can alter my determination. It’s either change parts or I won’t go at all. We’ve had that thing pounded into us for a month—it seems years to me—and every word of Max Schmidt’s opera is beaten into the brains of every one of us. I believe I could sing the tenor’s part; and you could, too. There are only two or three of Gretchen’s songs that you need go over at all,—”

“But I won’t! I won’t lend myself to any such thing—”

“Olive, how dare you say won’t to me! I’m saying it; and two people can’t won’t at the same time. My reasons are sound; my decision is final! I haven’t soaked myself with camphor here in the dark for nothing. I mean business. So don’t ask me any questions.”

“But think of the chagrin of the rest of the cast! Don’t you know this whole thing is built around you? The idea of me, little old me, trying to sing a part that people expect to hear you in.”

“Cousin Olive, I’m deeper than I look. I have particular reasons, most particular, for making this change. Please be a good girl and help me. If you knew, if you only knew,—”

“I’m sure there’s fraud in it somewhere. But—”

“But you’ll do exactly what I tell you, like a nice little girl, to please your loving cousin.”

“I’m afraid so,” said Olive, reluctantly. Zelda smoothed back her hair from her forehead and threw the long black braid over her shoulder.

“And now will you kindly—I’m treating you as though you were a maid-of-all-work—will you be kind and forgiving enough to throw me that other bath-wrapper from the closet—it’s a queer-looking pink thing—this one is smothering me—and I’ll be obliged to you. Then we can go to work.”

Zelda brushed her hair at the dressing-table, breaking out occasionally into a fit of laughing. She rose suddenly in the majesty of the bath-wrapper and sang one of Christine’s songs with animation, waving her hairbrush in the air:

“Again, O love, through peaceful hills

To lift the song.

Again the willing labor sweet,

The toil, the rest;

Once more, O love, we turn with hopeful hearts

To home and rest!

“Fräulein”—she broke off abruptly in an imitation of Professor Schmidt’s voice and manner—“Fräulein, dot ist most luffly. Only ven you say ‘Vonce more, O luff,’ you should droop your eyes, Fräulein, shoost like dot!”

Olive watched her cousin wonderingly.

“Zee Dameron,” she said gravely, “I sometimes wonder whether you are not acting all the time.”

“Please don’t, please don’t say that.” And there was a sad note in Zelda’s voice. “But now let us go down and run over these charming classics of Herr Schmidt’s on the piano. We can shift his characters, if he can’t!”