CHAPTER XXXIV

A NEW UNDERSTANDING

Rodney Merriam opened the door and greeted Zelda cheerily.

“Am I not the early bird?” she demanded, walking into the library and flinging at its owner her usual comment on its eternal odor of tobacco.

“I’ve been here early in the morning and late at night, mon oncle, and it’s always the same. I’m glad to see a cigar this morning. It’s the pipe that I protest against. You’re sure to have a tobacco heart if you keep it up.”

“You’re a trifle censorious, as usual,” said Merriam, looking at her keenly. “How can I earn your praise? Do you confer a medal for good conduct,—I’d like one with a red ribbon.”

“I shan’t buy the ribbon till you show signs of improvement. I had hoped that you would congratulate me in genial and cheering words. It’s my birthday, I would have you know.”

“At my age,—”

“You’ve said that frequently since we got acquainted.”

“As I was saying, at my age, birthdays don’t seem so dreadfully important. But I congratulate you with all my heart,” he added sincerely, and with the touch of manner that was always charming in him.

“Thank you. And if you have—any gifts?”

He marveled at her. He had rarely seen her more cheerful, more mockingly herself; and he was proud of her. He had told her a few hours before that her father was a scoundrel, and she had left his house in a rage. She could now come back as though nothing had happened. She was a Merriam, he said to himself, and his heart warmed to her anew.

He drew out the drawer of his desk.

“Of course I haven’t any gift for you; but there’s some rubbish here—hardly worth considering—that I wish you’d carry away with you.”

He took out a little jeweler’s box and handed it to her.

“I’ve rarely been so perturbed,” she said. “May I open it now, or must I wait till I get home,—as they used to tell me when I was younger.”

“If you’re interested in an old man’s taste, you may open it. I’m prepared to see you disappointed, so you needn’t pretend you like it.”

She bent over the gift with the eagerness of a child, and pressed the catch. A string of pearls fell into her lap and she exclaimed over them joyously:

“Rubbish, did you say? Verily, I, that was poor, am rich!”

She threw the chain about her neck and ran it through her fingers hurriedly; then she brushed the white hair from Rodney Merriam’s forehead and kissed him.

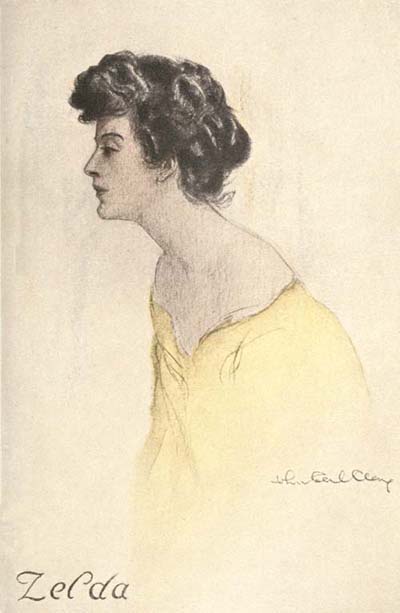

Zelda

“You dear: you delicious old dear! I know you hate to be thanked—”

“But I can stand being kissed. Put those things away now; and don’t forget to take care of them. You can give them to your granddaughter on her wedding day.”

“I can’t imagine doing anything so foolish. I can see myself cutting her off without a pearl.”

The suggestion of poverty carried an irony to the mind of both. Her father was a rascal, who had swindled her out of practically all of her fortune. He was a lying hypocrite, Merriam said to himself; and here was his daughter as calm and cheerful as though there were no such thing as unhappiness in the world. His admiration and affection rose to high tide as he played with the pipe that lay by his hand on the table.

“Smoke it if you like,” said Zelda. “This curse of habit, how it does take hold of a man! But a man who gives pearls away in bunches,—well, he may make a smoke-house of his castle if he likes.”

“The smoke-house suggestion isn’t pleasant, my child. Pearls are spoken of usually as being cast before animals whose ultimate destination is the smoke-house. Please be careful of your language.”

“I don’t care to be roasted or smoked. I have come to talk business and I wish you to deal graciously with me, as becomes the noblest uncle in the world in dealing with his young and wayward niece.”

He filled the pipe from a jar, and she grew grave, watching him press the crinkled bits of dusky gold into the bowl, for now she must talk of her father and her own affairs seriously. The light of the match flamed up and lit the stern lines of Rodney Merriam’s fine old face. He threw the stick into a tray.

“Yes, Zee,” he said very kindly.

“I’m sorry if I seemed a little—precipitate—yesterday. But it was all new and strange. And I have known that you did not like father. You will overlook whatever I did and said yesterday, won’t you?”

There was a note of real distress in her voice.

“It’s a good plan to begin the world over every morning. I want to help you in any way I can, Zee. I began at the wrong end yesterday. The fault was all mine!”

“Father and I have had a long talk about his business. He approached it last night on his own account. I have told him that I was coming to you.”

“Yes; it is better to have told him that.”

She felt quite at her ease, and his kindness encouraged her.

“Father has met with misfortune. He has told me frankly about it: he speculated with the money that belonged to me—and the money is all gone.”

“Yes; I am not surprised.”

“There is the house we live in and the farm,—they are still free. He says they belong to me.”

“If he has not pledged them for debt in any way, they pass to your possession to-day. They are yours now.”

“Yes; I understand about that. This is my fateful birthday;” and she smiled.

He smoked in silence, wondering at her.

“But there are some things that are not quite right. Father has told me about them. There is something about an order of court, which affects a piece of property that he has sold through this Mr. Balcomb. Father takes all the blame for that. I suppose that is what you wished to tell me last night. But I’m glad I heard it from father. I hope you will not be hard on him. He has talked to me in an honorable spirit that, that—I respect very much.”

The sob was again seeking a place in her throat and her eyes filled, but she looked straight at her uncle till the old man grew uncomfortable, and stared at the bronze bust of Abraham Lincoln on the mantel and wished that all men were honest, and all women as fine as this girl.

“Uncle Rodney, I wish to protect father fully in every way from any injury that might come to him for what he has done. I understand perfectly that it was a large sum of money that he lost; but he is an old man and he was doing the best he could.”

The color climbed into Merriam’s face and he smoked furiously. The idea that Ezra Dameron had done the best he could, when he had sunk to the level of a common gambler, wakened the wrath against his brother-in-law that was always slumbering in his heart.

“Zee!” he exclaimed, suddenly appearing through his cloud of smoke,—“Zee, he isn’t worth it!”

“Please don’t!”—and the sob clutched her throat again—“I didn’t come to ask what it was worth; but to get you to help me.”

“Yes. Yes; to be sure. It must be done your way,” he replied quickly.

“But it’s the right way. Now I want you to tell me what to do. People have bought property of my father, and he failed to get the approval of the court. I’m not sure that it was his fault,—it must have been Mr. Balcomb’s way of doing it. But it makes no difference, and father takes all the blame. Now a title given in this way is not right,—is that what you say?”

“We say usually that titles are good or bad,”—and he smiled at her.

“But there must be a way of making this good.”

“Yes; perhaps several ways. That is for a lawyer. You are the only person that could take advantage of an omission of that sort, I suppose.”

“That is what I wish to know. And it wouldn’t be very much trouble to make it right.”

“We must ask a lawyer. Morris understands about it. He is considered a good man in the profession. The advantage of calling on him is that he is a friend and knows Balcomb.”

“I told father I might ask Mr. Leighton to help us.”

Rodney looked at her quickly. Ezra Dameron, Zelda his daughter, and Morris Leighton! The combination suggested unhappy thoughts.

“Morris is coming up this morning. He said eleven, and he’s usually on time. That’s one of the good things about Morris. He keeps his appointments!”

“I imagine he would. Uncle Rodney, I’m going to ask you something. It may seem a little queer, but everything in the world is a little queer. Did you ever know—was there anything,”—it was the sob again and she frowned hard in an effort to keep back the tears—“I mean about mother—and Mr. Leighton’s father?”

The blood mounted again to the old man’s cheek, and he bent toward her angrily.

“Did he throw that at you? Did Ezra Dameron, after all your mother suffered from him, insult you with that?”

“Please don’t! Please don’t!” and she thrust a hand toward him appealingly. “I used to see the word past in books and it meant nothing to me. But now it seems that life isn’t to-day at all; it’s just a lot of yesterdays!”

The old man walked to the window and back.

“It was your mother’s mistake; but it must not follow you. When did your father tell you this?”

“Yesterday,—last night. I had provoked him. It is all so hideous, please never ask me about it—what happened at the house—but he told me about that.”

“He’s a greater dog than I thought he was; and now he has thrown himself on your mercy! I’ve a good mind to say that we won’t help him. Morris’s father was a gentleman and a scholar; and Morris is the finest fellow in the world.”

“Yes; but please don’t scold! It won’t help me any.”

“No; I can’t ever scold anybody. My hands are always tied. I’m old and foolish. Talk about the past coming back to trouble us! You have no idea what it means at my age; it’s the past, the past, the past! until to-day is eternally smothered by it.”

He cast himself into his chair; and she laughed at him—a laugh of relief. His anger had usually amused her by its lack of reason; it gave her now a momentary respite from her own troubles.

“I’ve never got anything in the world that I wanted. Here I hoped that you and Morris might hit it off—”

“Please don’t,—”

“But you wouldn’t have it; you’ve treated him most shabbily.”

“I shouldn’t think he would have told you anything about it,” she said with dignity.

“Of course he didn’t tell me anything about it! Don’t you think I know things without being told?”

“I don’t envy you the faculty,” she said, with a sigh. “I’m not going to look for trouble. It all comes my way anyhow.”

Her tone of despair touched his humor and he laughed and filled his pipe again; then the bell rang and he went to open the door for Morris.

“Morris,” he began at once, “we can omit the preliminaries this morning. Mr. Dameron’s trusteeship has expired. His daughter is entitled to the property left her by her mother, or its equivalent. There has been a sale of property that is not quite regular, and—”

“We wish to make it quite legal,—quite perfect,” said Zelda.

“And we wish to avoid publicity. We must keep out of the newspapers.”

“I understand,” said Morris.

Zelda had purposely refrained from mentioning her father’s own plan of continuing himself as trustee to hide the fact of his malfeasance; but with Morris present, she felt that her uncle was easier to manage.

“We have agreed to continue the trusteeship, just as it has been. Father and I have had a perfect understanding about it.”

“No! no! we won’t do it that way,” shouted Merriam.

But Zelda did not look at him. Her eyes appealed to Morris and he understood that in anything that was done, Ezra Dameron must be shielded; and the idea of hiding Dameron’s irregularities struck him as reasonable and necessary.

“You can give your father a power of attorney to cover everything he has left of yours if you wish it,” said Morris.

“I won’t hear to it; it’s a farce; it’s playing with the law,” declared Rodney.

“Uncle Rodney, I’m glad the law can be played with. There’s more sense in it than I thought there was. You will do it for me that way, won’t you—please? And there are some people who have paid father for an option on what he calls the creek property. I wish to protect them, too.”

“You needn’t do that,” said Morris. “We can repudiate the option probably. It’s not your affair, as the law views it.”

“But I wish to make it my affair. I wish to do it, right away. I’ve heard that important things can’t be done right away, but these things must be,”—and she smiled at Morris and then at her uncle.

“You understand, Zee, that if you give this power of attorney you are brushing away any chance to get back this money.”

“Yes; perfectly. And now, Mr. Leighton, how long will it take?”

Morris looked at Merriam as though for his approval.

“Uncle agrees, of course, Mr. Leighton. You needn’t ask him,”—and the two men laughed. There was no making the situation tragic when the person chiefly concerned refused to have it so. She had accepted the loss of the bulk of her fortune and the fact of her father’s perfidy without a quaver. She seemed, indeed, to be in excellent spirits, and communicated her cheer to the others.

“If this is final—” began Morris.

“Of course it’s final,” said Zee.

“I’ll come back here at four o’clock and you can sign the power of attorney if you wish. But there’s one thing I’m going to do—on my own responsibility, if necessary. I’m going to get back that option on the creek strip that Mr. Dameron gave my friend Balcomb. Balcomb’s a bad lot, and I’m not disposed to show him any mercy.”

“I’d rather you didn’t—if my father pledged himself to sell—”

“Let Morris do it his way,” begged Merriam. “You may be sure Balcomb won’t lose anything.”

“I’m afraid he won’t,” said Leighton, and left them.

“Sit down, Zee,” said Merriam, as Zelda rose.

“I must go back to father,—you can imagine that these things haven’t added to his happiness.”

“Humph!” and Rodney folded his arms and regarded Zelda thoughtfully.

“I wish you wouldn’t say ‘humph!’ to me, mon oncle! It isn’t polite.”

“Zee,” said the old gentleman, kindly; “what do you intend doing? I suppose you have no plans,—but you must let me make some for you.”

“Of course I have plans; they are all perfected, and they are charming. There’s no use in talking to you about them. I’ve given you enough trouble.”

“I hope you’ll give me more! As long as my troubles are confined to you I’ll try to bear them.”

“Oh sir, thank you,—as the young thing always says to the good fairy uncle in the story-books. Well, as you seem sympathetic I’ll tell you. You remember that little Harrison Street house where Olive lived? Well, they owed father some money and the house was mortgaged. Olive wouldn’t let me release the mortgage,—or whatever they call it; but it’s the dearest house in town. Olive and her mother are going to move into a flat. I loved that house the first time I stepped inside of it. Well, I’m going to sell the farm and the old house where we live, and anything else we happen to have, and move to Harrison Street; and I’m going to give music lessons; and I can get a place to sing in a church whenever I please. I’ve had offers, in fact. It’s all perfectly rosy and beautiful,—” and she stretched out her arms and played an ascending scale of felicity in the air with her fingers. “Perhaps, sometimes, you will come over to see us in the new place!”

“Zee, I have sometimes hoped that you had a slight feeling of affection for me;” and Rodney Merriam’s face grew severe.

“How you do flatter yourself! Go on!”

“And I want you to do something for me.”

“If it’s sensible I’ll consider it.”

“I want you to go home and pack up and come down here to live with me. And I beg of you don’t talk about giving music lessons and moving to that Harrison Street hovel,—even as fun it doesn’t amuse me. Come now, be a sensible girl. How soon can you move?”

“You seem to be addressing me in the singular number. There are two of us to plan for.”

Her lips quivered and the tears came to her eyes. Here was the old question of her father, that had been a vexation all the long year through. If only she might be suffered to manage her affairs alone!

“Please let me go! You have been so kind to me—I should hate awfully—”

“But Zee,—we must be reasonable. You are young, and your way must be made as easy as possible—for the road’s a tough one at best. It seems a hard thing to say, but your father is no proper companion for you. I can arrange for him in some way; but I owe it to you, to your mother’s memory, to keep you apart. I haven’t anything else to do but care for your happiness; and your father doesn’t fit into any imaginable scheme of life for you.”

Zee laughed.

“Please don’t imagine schemes of life for me. I have one of my own, and it’s quite enough. And my mother,—”

“Yes, your mother, Zee.”

“My mother—was a good woman, wasn’t she, Uncle Rodney?”

“She was a wonderful woman, Zee.”

“And she did what she thought was right, didn’t she?”

“She certainly did.”

“And do you think—is it reasonable to believe—that she would be pleased to know that I had abandoned father because he had been unfortunate, even criminal, if you will have it so? Do you think, Uncle Rodney, that to leave him in his old age would be quite in keeping with your own idea of chivalry? I’m sorry to know that you would propose such a thing. I should like to have your help, but I don’t want it on any such terms,—on any terms.”

She spoke very quietly and waited patiently for anything further that he might have to say. The clock on the mantel struck twelve and across the town the whistles were blowing lustily the noon hour. Merriam lifted his clenched right hand slowly and opened and shut it several times, then dropped it to his knee.

“Zee,” he said, “you shall do it your own way,”—he smiled—“with a few exceptions. You are right about it. Your mother would like you to stand by your father. I can’t even say what is in my heart about him; but I had counted on—having you—now—for myself.”

And the old man’s face twitched from the stress of inner conflict. Zelda crossed to his chair and threw her arms about him.

“Dear Uncle Rodney!” she cried, and then sprang away, drawing him up by his hands.

“I’m going to be a lot nicer to you than I ever was before,” she declared. “And you will help me to be good!”

“There are two or three things that I want you to do for me, Zee. I ask you as a favor,—as a very great favor.”

“It’s going to be something hard,—but go on!”

“Let me be your banker. And don’t begin teaching or making yourself ridiculous in other ways. I have enough, and I want you to begin having the benefit of it now. And I should like you to keep the old house up there, for a while, at least. My father built it, and I was born there—and your mother—and you! I should hate to have it pass to a stranger, in my day. And another thing. You’ve done a beautiful but not a very sensible thing in continuing your father in charge of your business—what’s left of it; but you’d better let me—consult with him about matters.”

“But you won’t—scold, or be disagreeable?”

He smiled at her words, which seemed ridiculous when applied to the squandering of a comfortable fortune, under circumstances that did not appeal to his pity.

“I’m not going to be hard on your father. My enemies have always escaped me. I suppose it’s because I’m so amiable.”

There was a pathos in his figure as he stood, quite free from his chair, his hands thrust into the side pockets of his coat, his shoulders a trifle drooped, and the half-smile upon his face marking still his inner reluctance.

“Zee,” he said, and he swayed a little, and put out his hand and rested his finger-tips on the table,—“Zee, you are the finest girl in the world. I wish you would tell your father that I shall be up to see him soon. And don’t worry about what I shall say to him. You can be there if you like.”

He followed her to the step, looking after her as she walked swiftly away, kissing her fingers to him from the corner.

Across the street, in Seminary Square, the wind was driving the leaves hither and thither aimlessly in the warm October sunshine, and it stole across to Rodney Merriam and played with his fine white hair. The branches of the park trees were so thinned now that he could see clearly the bulky foundation of the new post-office. He sighed at the thought of the changes that must come, watched the procession of automobiles and wagons in High Street, and glanced at the uncompromising lines of the overshadowing flat whose presence never ceased to annoy him.

Then he anathematized it under his breath and went in and abused the Japanese boy because luncheon was not ready.