Episode One

Root, Boot and Toot

The subtitle of this episode is Root, Boot and Toot because my grand parents came from a village called Basti in Uttar Pradesh of India and this was their root. However, while my grand parents were working on the sugarcane plantations of the Colonial Sugar Refining Company in Fiji as indentured workers from 1906 to 1916 after being uprooted from their root they were treated very badly by the overseers on the farm. My grand parents were beaten, whipped and kicked by the boot of these cruel sirdar.

But their life became better when they received their freedom and established their own farms. Their wagon of family life began to toot with joy and pride.

This is a sad and tragic true story of my grand parents, Sarju Mahajan and Gangadei from 1906 to 1986. It is full of emotive events that go on to show how their blood, toil and sweat went on to make valuable contribution to develop their family life first and then assist the country and the Colonial Sugar Refining Company prosper in Fiji.

In order to get these detailed episodes from them I had to do my share of service to them by showing my love and compassion for them. When I used to read the chapters of the Hindu Epic Ramayan to them every evening they would narrate their stories of migration from Basti in Uttar Prades in India to Botini in Fiji very slowly and gradually after the conclusion of the reading.

In the process of that narration they laughed, cried, got angry and showed intensive remorse. Sometimes while telling their tragic stories they became so emotional that I had to leave them alone to cool themselves.

When slavery was abolished by the revolutionist William Wilberforce from this world then the attention of the large farm owners in the British colonies turned to India. By 1879 the turn of Fiji came to recruit young and healthy vulnerable Indian by deceitful methods and questionable means to ship them to Fiji to work on the farms of the then Colonial Sugar Refining Company.

Fiji is a nation of over 300 islands in the South Pacific Ocean. Fijians, Indians, Europeans, Chinese and others have been living in reasonable harmony for over two centuries. Fiji’s climate is tropical with adequate rainforests and pine plantations. Indians do cultivation of sugarcane and there are coconut palms galore. A country of uncertain political and economic future but has to support at least three quarter million people. This country is my motherland and I have a special feeling for the place.

The Fijian Chiefs ceded Fiji to the British Government in 1874 but the natives were not culturally ready to participate in the economic development of the country. So the British Government in conjunction with some multinational enterprises went to other colonies to bring people who could be manipulated to help them achieve their economic goals.

The Colonial Sugar Refining Company with the help and support of the British Government was willing to exploit the situation and enter the scene of the so-called economic development of the country. The Company hired cunning recruiters (Arkathis) to visit various villages and cities of India to recruit young and healthy Indians who could work on the sugarcane plantations and orchards belonging to them.

They in turn recruited Indian Priests and Village heads to do the initial ground work for them because the people there could trust these men. Thus began the Indenture System for the Colony of Fiji in 1879 . It is commonly known as Girmit.

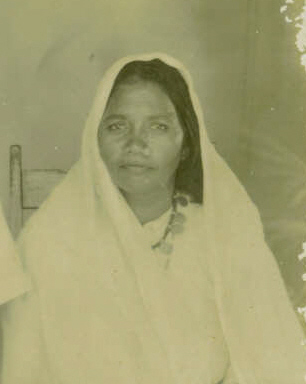

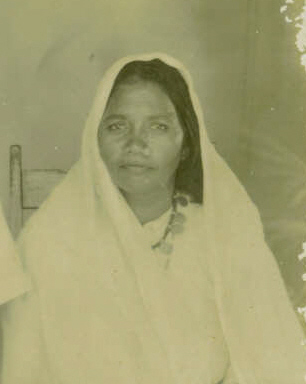

Gangadei my grand mother

Gangadei was my grand mother. She was a pretty girl and was as calm as her name sounds. She was born in Sitapur in the district of Basti Uttar Pradesh (North India). She was the last of the four children of the farming family. Very little else is known about her childhood but she was an intelligent and a strong woman.

She was a twelve-year-old girl when she accompanied a group from her village to go to the annual Ayodhya Festival, a religious gathering of villagers. This festival used to be so crowded with people that once one is lost it would be impossible to locate them easily.

It was in that massive crowd of people that my grand mother got separated from the village group. She felt alone and frantically began searching her group but alas there was no hope. Tired and hungry she decided to sit down in a corner completely disappointed. At that time her condition was like a fish detached from water.

Where could she go? Who would help her? What should she do? She was confused and did not know what to do. She had lost her thinking power altogether in this confusion. ‘Into thy hands Lord, I commend my Spirit.’ Nothing remained in her own hands, everything in His.

A yellow robed pundit of middle age saw my grand mother’s condition and expressed his wish to assist her. Such people were respected in the village and she felt at ease to talk to him. He spoke kindly, “Beti, why are you crying? Have you lost your way? Have you lost your family members? You don’t worry because as a holy man I am here to help you.”

My grand mother felt that this help was god sent and she greeted the pundit with respect and told him her sad story. Punditji realised that my grand mother was in real need for his assistance and this made him very happy. The pundit however, hid his real eager feelings and expressed his concerns and pseudo sadness as if his own daughter or sister was in trouble needing his assistance.

He pacified my grand mother and expressed his sorrow. May have shed some crocodile tears and said, “Well, whatever was to happen has happened but now you do not have to worry any more. I am here for you. I am calling a rickshaw to take you home.”

Whatever my grand mother longed for, this middle-aged Brahman was prepared to deliver so she fully trusted him and agreed to return home with him. The pundit made a signal to a nearby rickshaw operator who was eagerly waiting for him. They sat in it and left the busy festival ground to a destination unknown.

My grand mother was eager to reach home but instead she arrived at a Coolie Depot and then she realised that this fake pundit was an agent (Arkathi) to recruit workers for the Indenture System. She cursed herself for trusting him but it was too late now. She was a prisoner in this Coolie Depot from where it was impossible to escape. There were various other unfortunate souls sitting and cursing their fates there and were unsure of their future.

The next day all the recruits appeared before the resident magistrate to register themselves as slaves to work in a foreign land. After the registration for girmit they were put on a cargo train bound for the port of Calcutta.

When my grand mother reached the Depot in Calcutta she could not believe her eyes when she witnessed the dilapidated nature of the place. Her worry and sadness multiplied manifolds but she could not do anything else but cry.

The late Sir Henry Cotton in his report to the British Parliament writes this on Girmit Recruitment Procedure:

In too many instances the subordinate recruiting agents resort to criminal means inducing these victims by misrepresentation or by threats to accompany them to a contractor’s depot or railway station where they are spirited away before their absence has been noticed by their friends and relatives. The records of the criminal courts teem with instances of fraud, abduction of married women and young persons, wrongful confinement, intimidation and actual violence- in fact a tale of crime and outrage which would arouse a storm of public indignation in any civilized country. In India the facts are left to be recorded without notice by a few officials and missionaries.

The new recruits suffered great injustice at the hands of the clerks and agents at the depot. Men and women were forced into small rooms like animals. Men and women were compelled and forced to get into pairs and then they were declared wife and husband. Those that did not agree were locked together and the men were instructed to make the women agree. Those who failed to come out as pairs were punished severely.

This pairing that turned into illegitimate marriage gave the agents publicity that the indenture system was conducted with the consent and willingness of wife and husband. This was far from the truth. In most cases the forced pairing led to social disaster and in some it turned out to be a blessing for the recruits because they could share their sorrows and grief.

It was in this Calcutta Coolie Depot that my grand mother met my grand father. My grandma’s case was a sad one. She worried a lot about her future and the forced pairing so she decided to choose my grand father as her husband because he was from the same district (Basti) and he was strong and handsome.

That was the beginning of their family life and the authorities registered their marriage. At least this staying together and the possibility of being able to share their pains, aches, friendship and difficulties made them feel a little better and bring some happiness in the wilderness.

C F Andrews wrote this in his report that those who were all chaste and honourable women became mixed up almost from the first day with the other class. How many of them remained chaste, even upto the voyage, it was impossible to say.

My grand father was Sarju who was born in Dumariaganj in Basti Uttar Pradesh in India. His father Shankar had a farm where he grew mangoes and other fruits but since there were four other brothers in the family my grand father at the age of fourteen was asked to work for a landlord in the next village of Senduri at almost no pay but only keeps.

One day my grand father was caught putting a few ripe mangoes in his bag to take home so he was branded a thief. This stigma became unbearable for a growing and honest young man of fourteen. He knew he would be ridiculed if he went home so he left this landlord in search of other jobs elsewhere.

He walked a long distance in search of work, which was not that easy to find. He reached Kashipur but he had not even reached the town when he was spotted by a cunning recruiting agent (arkathi).

After noticing the predicament my grand father was in, the recruiting agent took advantage of the situation. He started a friendly conversation with my grand father, which went somewhat like this:

“How are you my friend? Are you looking for work?” asked the agent.

“What kind of work sir, and what would I get as wages?” my grand father wanted to know.

“Well, my friend, this is not work at all,” the cunning agent said in order to trap my grand father.

“In fact, you are indeed lucky and certainly you are destined to becoming very rich and famous soon. There is a beautiful island off the coast of Calcutta known as the Ramneek Dweep or the paradise in the Pacific.

A very rich landlord resides there and he needs the services of a security guard to look after his home and the farm. You will get full uniform, food ration and a farmhouse to live in. You will only work for twelve hours a day with a gun hanging across your shoulder marching up and down the entire property. You cannot find such a lucrative job anywhere here because you will just enjoy your daily tasks and even earn money. What else do you want?”

My grand father felt very good and began imagining himself as a security guard with a gun hanging across his shoulder marching up and down the property in the day and enjoying life in his farmhouse at night. This sounded like heaven to him. He began to dream about his future life full of fun. He was not prepared to hear any more but to sincerely thank the agent and agreed to travel immediately. The agent felt good to trap another recruit.

Seeing that my grand father was tired and hungry the agent took him to a nearby eating-house and fed to his hearts content. Then they got into a rickshaw to start their journey to the dreamland. But when they reached the coolie depot my grand father’s hopes were shattered and he felt disappointed with himself for believing such stories of the agent and falling into his trap.

When my grand father saw the crowd of people he regretted his every move. He too joined the other unfortunate victims in the depot to hang his head down and cry. He too felt like an animal in a strong cage unable to find its way out.

He began thinking that his village was much better place to live a free life than this dungeon. He was told by some recruits that he will be in Fiji where he would work long hours on sugarcane farms owned by white men. He will have to sweat from head to tail twenty-four hours a day and tolerate the harsh treatments of the field officers. He was not able to imagine the reality of the situation then but when in Fiji he told me all.

There was nothing he could do to get out of this depot because of very tight security there. At last one day he too was presented to the office of the magistrate who asked him only one question, “Do you agree to go to this island to work as a labourer?”

“Yes sir!” answered my grand father as the recruiting agent had instructed him.

Thus his five-year contract (girmit) was signed and sealed. He was a slave. Similar fate awaited thousands of others who were waiting to get on board a cargo ship Sangola Number 1 in 1906.

There were women, children and men. Everyone’s heart was filled with pain and sorrow and the eyes were wet with tears. Some were sobbing for their relatives and family members, others missed their parents, and yet there were others who lamented the loss of their motherland. My grand father described that inhumane coolie depot as the hell on this earth.

The Clerk of the Court in a communication admitted that it was perfectly true that terms of the contract did not explain to the coolie the fact that if he or she did not carry out his or her contract or for other offences, like refusing to go to hospital when ill or breach of discipline, he or she was to incur imprisonment or fine.

According to Richard Piper, Indians in India believed in very strict caste system but all caste restrictions were ignored as soon as an immigrant entered the depot. For the poor unfortunate who happened to have some pride of birth, there was a bitter but unavailing struggle to retain their self-respect which generally ended in a fatalistic acquiescence to all the immorality and obscenity of the coolie lines. The immigrants were allowed to herd together with no privacy or isolation for married people.

My grand father and grand mother both admitted that no one who survived at the end of the journey could distantly have faith in the caste system. They were all simple human beings and to call himself or herself Brahmans, Chatriyas, Vaishyas or Sudras or even Hindu or Muslim was foolish to say the least.

Sarju and Gangadei were two of those unfortunate souls who fell victim to the Indenture System of 1879 onwards. Indians lived in poverty but they were subsistence farmers enjoying their lives with their respective families and so were Sarju and Gangadei who were just healthy adolescents.

The late Sir Henry Cotton explained that the recruiter or arkathi lay in wait for wives who had quarrelled with their husbands, young people who had left their homes in search of adventure and insolvent peasants escaping from their creditors.

When one form of slavery was abolished in the western world then another kind of deeper slavery began from the Indian Continent. This was called Girmit or the Indenture System. The dreadful life of the recruits and the atrocious treatment they got from the overseers was inhumane and cruel.

Rev Andrews mentioned in his book that before they had been out at sea for two days in the stormy weather a few of the poor coolies were missing. They either committed suicide or hid themselves in the hold. They were dragged by the officers and kept alive but they too lost their battle with life.

Upon entering the depot my grandparents were issued with two thin blankets and a few eating utensils made from tin. At dinner time all the recruits were made to sit on the ground in a line and served dhal and rice. Some hungry recruits were frantically eating but there were others who were submerged in deep thoughts about their losses of religion, family members and national pride.

My grand father sat there quietly for a while because he could not collect enough courage to eat such food in such a situation. The clerks advised him that it was no use worrying about petty religious, social and family matters any more. Life for him had changed and he had to accept it. There was no return to their usual families. This was a hard fact of the system.

He prayed hard. ‘O Lord I give you my heart and soul; assist me in my agony; may I handover all my future into your safe and powerful hands.’

Twamewa Mata ch Pita Twamewa

Twamewa bandhushch Sakha Twamewa

Twamewa Vidya Dravinam Twamewa

Twamewa Sarva Mum Dev dev

Whether his prayers were heard or not but time and days kept moving. They do not stop for anyone or any event. The recruits were loaded on the cargo ships and were allocated a small place on the deck that was dirty and wet. The mood, condition and situation on the ship were so drastic that the recruits began to feel ill. Some kept vomiting for a long time and those that could not tolerate the unhealthy and un-socialised circumstances jumped into the sea to end their ordeal.

The recruits suffered for days and could not eat the poorly cooked khichdhi that was dished to them daily. If the weather became bad and the food could not be cooked they were given dog biscuits. The recruits had to suffer the heat, rain and cold on the deck. The journey was long and dangerous.

Many of the human cargo lost their lives through hunger, torture and suicide because they could not bear the cruelty and suffering onboard the ships. However, both Sarju and Gangadei survived the atrocities and were united as a family unit to work on the sugarcane farms in Matutu in Sigatoka.

Pandit Madan Mohan Malaviya said that the condition under which the labourers lived on board the cargo ships were not good at all. There was not enough care for the modesty of the women, and all castes and religious rules were being broken and it was no wonder that many committed suicide or else threw themselves into the sea.

The sea journey of the coolies lasted a few months and at last the boat anchored near a small island in the Fiji Group in November 1906. This was Nukulau, a quarantine station.

It was here that the recruits were washed with phenyl and examined to give them certificate of fitness so that they could be auctioned. My grandparents were bought by the Colonial Sugar Refining Company based in Sigatoka and were transported to Matutu where they were given eight feet by eight feet grass huts that were not fit for human inhabitation but there was no other choice.

These huts had wet and hard floor and a few blankets were allocated to them. Their first ration of rice, dhal, sharps, salt and oil was also handed to them. If they completed their daily tasks well for a month then they were paid ten shillings for that month.

My grandparents recalled that the white men who were called Kulumber or Sirdar allocated daily tasks to the workers or girmitiyas and if any weaker person was not able to complete the tasks satisfactorily they were beaten with whips, fists, kicks and sticks. They had to tolerate all the injustice because there was no place or institution to register their complaints.

Despite the fact that my grand parents were both strong and good farmers and managed to complete their daily tasks well, initially they too suffered a lot of beating and injustice at the hands of the white men. However, one day towards the second month when the Sirdar was abusing my grand mother, my grand father could not tolerate it any more because enough was enough for him.

He was using a long handled hoe to complete his task and used this to beat the hell out of the white man. This kind of self-defence happened a few times and then both my grand parents were free from any violent attacks but the verbal abuses never ended.

My grand father encouraged other workers or girmitiyas to stand up for their self-defence but only a few could do this to protect their self-respect. One of them was Tularam who converted to Islam and became Rahamtulla. He was my grand father’s jahaji bhai or ship mate and established himself as a farmer in Botini later.

Instances of such deep friendship were many in those days of the indenture system and these lasted for the life time of the workers. The friends could stand for each other in times of hardship and any other difficulties.

On the CSR plantation they were made to work hard, for long hours and suffered cruelty and abuses of the sector officials if they made the slightest of mistakes. Like many other workers or Girmitiyas they too were whipped, kicked and beaten by the Sector Officers. There was no one to hear their complaints and thus they could only blame and curse their ill fate and they could do nothing to escape these hardships.

Whilst in Matutu my grand parents had many good friends and one of them was Rambadan Maharaj who after his girmit became a shopkeeper. The two families interacted with each other long after my grand parents moved from Matutu to Botini.

The families despite their difficulties met regularly to continue with their cultural activities. My grand father with the assistance of Rambadan Maharaj had developed a great love for the Hindu Epic Ramayan. He could recite the couplets of Tulsidas from memory and explain the meaning to his friends.

My grand parents completed two difficult and deceitful contracts of five years each and gained their freedom from bondage in 1916. This freedom from slavery was a lot sweeter than the sugarcane. Their happiness was so great that it outweighed the sorrows and sufferings of their indenture.

By 1916 the Indenture System had stopped but my grand parents continued to grow sugarcane and other crops in Matutu until 1928 and then moved to Botini in 1929. Their first son Hiralal was born at the end of the indenture system.

My father Bhagauti Prasad was born in Matutu, Sigatoka in Fiji on 27th June 1918 and my mother Ram Kumari was born in Nabila in Sigatoka Fiji, on 24th July 1924. They got married in 1936 and lived happily in Matutu for a while and then shifted to Botini when the Second World War began.

They were one of the fortunate ones when as a result of their loyalty and hardwork they were rewarded by the CSR Company with a lease for a large piece of land in Matutu and in Botini in Sabeto to continue sugarcane farming. They had to cater for their family of three sons and five daughters by then and despite the option to return to India they chose to sign further contracts to supply their own sugarcane from their farms to the company.

There were valid reasons not to return to India at that time. Firstly, they did not have any contacts and did not know if their family members were still there in the same village. Then there was this fear that they might not be accepted in the community because they would be regarded as outcasts. Of course, although one way passage on a ship was provided, they did not have any other needed financial means to travel and settle in India.

However, my grand father went back to India to pay respect to his birth place in 1952 but had to return to Fiji to continue his family life because very few of his family members could be located in Basti by then. Frequent hurricanes, floods and internal infrastructure developments in India had dismantled and disintegrated the family. This was another price that the girmitiyas had to pay and the loss of their root was unbearable.

My grand father then put his eldest son Hiralal on one of the three farms in Botini and managed the other two himself with his other children. His second son Bhagauti Prasad managed the farm in Matutu until the farm was sold to Rambadan Maharaj when the world war two started.

His second son Bhagauti Prasad who had got married to Ram Kumari daughter of Bali Hari from a nearby village called Nabila, joined his father Sarju to manage the farms in Botini later.

World War two had just begun. Soldiers from various countries began to arrive in the country. Camps soon got established in strategic places in the main island and the army personnel began patrolling the areas on foot and on various types of vehicles. They were there to keep peace but they were definitely disturbing the peace of the village people.

Inhabitants of the small village were all cane farmers who were brought from India as indentured labourers by the Colonial Sugar Refining Company. After completing their hard earned indentured contract of five or ten years they were free to settle as cane farmers or return to their motherland India.

Many chose to settle in this village on land allocated by the CSR Company. They had to enter into another one-sided contract to keep supplying sugarcane at stipulated price to the mills owned by the Company. A monopolistic situation gave no other choice to the poor farmers.

On many occasions upon supplying tons of sugarcane to the mills the farmers were told that they can not be paid because their product was dirty and it would cost the company more to clean the mills than to pay the farmers their share. The farmers had no alternative but to accept this wrong and sinful decision. There were no organizations of farmers to give them legal assistance until early 1950s. In order to subsist they had to do some mixed cropping.

CRS Company believed that they were doing the farmers a lot of favours because they had used recruiters to enrol them from various cities and villages of India, which in those days, like Fiji, was also a British Colony. They emancipated the labourers from stark poverty in India and resettled them in Fiji to prosper.

The village of Botini in Sabeto valley was the salad bowl of the country where farmers boasted growing best vegetables and other crops. Surrounded by the mountain range known as the Sleeping Giant or Mount Evans and the winding Sabeto river the villagers had great prosperity at their feet at all times.

Naturally they lived in good homes and had all the conveniences. The farmers worked very hard and lived in a united community that soon had their own educational and religious institutions for the development of their children.

It is in this background that my father Bhagauti Prasad, the second son of Sarju, having worked on the joint farms for several years began to do farm work on his own piece of land that was allocated to him by his father, my grand father Sarju. This new venture began in 1949. He was married with four children by then and the family lived at this new location until 1983 when they sold the property and moved to Nasinu near Suva.

They had two sons and two daughters at that time: Ramlakhan, Vidyawati, Vijendra and Shiumati. Other five daughters were born later.

So a family of eleven members enjoyed their family life working hard on their farm and living a happy life. Sarju Mahajan and Gangadei kept a watchful eye and kept blessing them to move on with their life as best as they could.

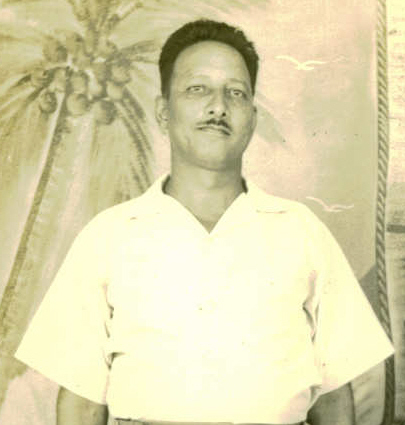

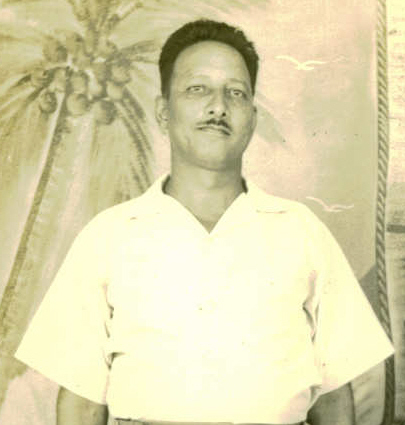

Bhagauti Prasad Ram Kumari

My Father My Mother