DAYS OF ACTION

The 1965 riots in Watts, a neighborhood of Los Angeles largely populated by blacks, forced the nation to focus attention on the problem of the ghettos and of racial oppression in America. The next few years saw the rapid growth of the civil rights movement, and of what Eric Sevareid described as the “Negro Passion,” evolving out of an “instinctive sense of justice.” [New York Post, May 5, 1963] The civil rights legislation of 1964 and President Lyndon B. Johnson’s War on Poverty programs addressed the issues of segregation and urban need and, consequently, furthered the civil rights cause.

The Society had been dealing with these issues for some time. In May 1961, Benedict had presented a proposal for an Urban Training Center to the Division of Home Missions of the National Council of Churches. The introduction to the proposal noted:

It is becoming increasingly obvious that it is in the scientific, technological culture of cities that the Christian Faith is being exposed to a totally new type of missionary situation. It is apparent to those who have spent considerable time in the completely urbanized sections of inner-city culture that no gimmicks or minor manipulations of church programs will make the church relevant.

The proposal stressed the importance of in-service training for city ministers, theological students contemplating inner-city work and inner-city laity, and urged the exploration of “the facets of urban life with which the Church must come to grips.” These included: city planning; the trade union movement; associations of commerce and industry; drama; the arts; television; radio; newspapers and magazines; politics and social work. The proposal received support, and in 1963 the Urban Training Center began operations at the First Congregational Church at Washington and Ashland avenues.

The Urban Training Center grew rapidly, helping clergy, seminarians, and other community workers to know the ghetto and to participate effectively and lead in Christian ministry programs relevant to the urban situation. Participants in the Urban Training Center’s program became involved with a variety of community organizations through field work arrangements, with each student alternating between work at the Center and work in the field.

In its most active period, from 1965 to 1970, the Center had about 2,000 students, approximately 90 percent of whom were trained for short periods of from 4 to 10 weeks. The remainder were involved for longer terms of 3 to 12 months. The many black participants in the Urban Training Center taught their white colleagues much about the black situation, and blacks and whites together learned a great deal about the urban problems of the 1960s. Some of the meetings evoked passionate reactions, including an occasional fist fight. But clergy and community organizers found that the Urban Training Center made significant contributions to racial understanding and urban strategy. It was here that the idea that “racism is a white problem” gained strength. Substantial Ford and Rockefeller Foundation grants and support from the Society and more than a dozen denominations and other organizations enabled the Center to flourish until 1970.

In the summer of 1966, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., came to Chicago and raised much hope as he rallied the poor people to his cause. A meeting with Mayor Richard J. Daley brought verbal pledges of support. However, very little positive action followed, and life in the ghetto continued as before. In one of his speeches in Chicago, King had quoted President John F. Kennedy’s comment, “Those who make a peaceful revolution impossible make a violent revolution inevitable,” and added, ‘‘I’m trying desperately to lead a nonviolent movement.”

In the fall of 1966, the Reverend James Bevel, who had worked directly with Dr. King, joined the West Side Christian Parish staff and became very influential in the life of the parish. The WSCP, in turn, established close ties to the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and its staff immersed itself in nonviolent civil rights struggles.

In 1963, Benedict had hired the Reverend Robert C. Strom as program assistant to the director to explore the place of Christian ministry in the civil rights movement. Strom’s participation in several civil rights demonstrations and sit-ins, from one of which-at the Chicago Board of Education-he was forcibly removed by police, led to legal actions and publicity, not all of which was viewed with favor by the Society’s Board of Trustees. Although Strom continued to receive support from the Society, he was attached from then on to the staff of the UTC. It was decided that the Society’s efforts to contribute to the civil rights struggle should relate to its particular organizational and localized setting.

Among these efforts was the expansion of the Society’s work on the West Side by the creation of an organization specifically concerned with unemployment. The Society’s existing organization in that area, the West Side Christian Parish, was a religiously oriented group which, for the most part, involved the women of the neighborhood. When it became clear that it did not meet the needs of the more militant neighborhood men who, above all, were concerned with unemployment, the Society agreed to help Archie Hargraves, Robert Strom, and Don Keating to form the West Side Organization for Full Employment. Success did not come easily.

Within one block of its 1527 W. Roosevelt Road location, the West Side Organization found that the Centennial Laundry, which employed 88 drivers, had hired only one black driver. In an effort to persuade the laundry to hire more blacks, WSO picketed and boycotted the business. The owner responded with a court injunction outlawing the boycott and picketing, and he sued the Society, as well as every member of the board, for $1 million each. WSO continued to exert pressure and, with the Society’s support, took the case all the way to the Illinois Supreme Court, which decided in its favor: the laundry was required to hire black drivers. This incident won WSO much community support and solidified its purpose and resolve. It also led the Society to put an indemnification clause in its constitution to protect its board members from lawsuits arising out of the actions of people who received aid from the Society.

In 1965, the West Side Organization formed the first Welfare Union in the United States to provide a grievance procedure by which welfare recipients could achieve rights guaranteed by law. Prior to this time, welfare recipients who had become victims of illegal actions by case workers in the administration of the welfare program, had had no effective means for recourse. In its first year WSO won all 450 of such complaints.

During the critical summer of 1966, the West Side Organization played an important role as advocate for citizens’ rights and as a liaison between the neighborhood people and the city’s power structure. And like many of the people it represented, WSO occasionally clashed with the police and the courts. When Benedict recounted one of these incidents to a suburban congregation and read the participants’ affidavits verbatim, his listeners appeared more upset by the language used in the affidavits than by the incident itself. As Benedict described it, “I think that the congregation was so shocked at the obscenities and bad language that they missed the point of the entire story. At any rate I apparently set in motion a great deal of ill-will against the Society for having confronted the congregation with the reality of the case.”

In the late 1960s the Society turned its attention to other programs and reduced its involvement with the West Side Organization. However, WSO continued its important work. Between 1966 and 1972 it launched several successful business ventures, including two Shell gasoline stations, a McDonald’s hamburger outlet, a paper recycling center, and a dry cleaning establishment. In 1971 the West Side Organization Health Services Corporation was formed to fight the effects of drug abuse, mental illness, and alcoholism. By 1980 the Health Services Corporation had a budget of more than $1 million and about 100 staff members serving urban residents.

The Society’s board was supportive of most of the programs developed in the early 1960s. However, as staff members increasingly participated in civil rights demonstrations, and as the Society’s involvement in housing projects entangled the organization in a series of lawsuits, there was a move to develop clearer guidelines for programs.

As a first step in this direction, Janet Gunn of the Society’s staff prepared position papers on welfare, fair housing, and public education. These formed the basis of intense discussions. Considerable debate centered around whether the Society should adopt a service-oriented course or should give financial support to programs based on self-help and self-determination and therefore administered by others. The decision was in favor of the latter course.

Adopted in 1966, the Guidelines affirmed the Society’s responsibilities to carry out Jesus’ injunction “to preach the Gospel to the poor, heal the broken-hearted, preach deliverance to the captives and set at liberty those who are oppressed.” Noting that the Society was” strongly interested in programs which seek ‘deliverance’ from the bondage of poverty and which aim at helping men to free themselves from domination by their environment, “the Guidelines went on to affirm the Society’s support of the nation’s political, economic, and legal commitment to “programs which…seek to create an equal opportunity for all men to participate in the social, economic, and political life of the metropolis. We believe full participation in the life of this world is essential to human dignity in the sight of God.”

While the Guidelines advocated nonviolence in all activities, they allowed that “where the law is unfairly administered or has an unjust effect, it is the responsibility of Christians to seek correction by legal means, [but] the individual Christian must always obey his conscience in response to his understanding of the will of God, accepting the penalty of such personal action.”

The Board of Directors took this occasion to clarify the Society’s intention to “concentrate on programs through which we can make significant and unique contributions to the solutions of important problems which face the metropolis” and to give priority to “unproven ideas of high potential “rather than” a proven project which others are able and willing to carry on.” In addition, the Society would encourage local decision-making and “the greater assumption of responsibilities by local groups and individuals.” Drawing on its historical traditions, the board reaffirmed the Society’s ecumenical stance and its determination to avoid partisan politics.

At the 84th Annual Meeting of the Society on November 20, 1966, Benedict charted the course.

Though the urban slum is now recognized as America’s No. 1 domestic problem, our strategy for solving it is inadequate…it does little to develop initiative by attacking the conditions which instill apathy and dependency in slum-dwellers. Under our present strategy the war on poverty and the war on slums are separate enterprises and the poor have little responsibility for either.

It is time for a self-help approach which entrusts the people of the slums with the principal role in combating poverty and eliminating slums, through their own local organizations and leaders and their own programs of individual community renewal. Business and industry could provide the technical skills and investment capital needed in such an approach. The church, through special agencies like the Chicago City Missionary Society, could serve as a “broker” to bring together the unused talent and energy of the slums and the capital and skills of the community at large.

The key was trust in the ability of members of the affected community to use the support of the Society in order to solve their problems in their own way. Too often the well-meaning “missionary” went into the depressed areas to help the poor but tried to do so by maintaining all control of a program imposed from the outside. Benedict’s approach was the opposite-the program, the leadership, and the control were to come from the people in the community. The Society would contribute capital and technical assistance and be the coordinator, the facilitator, and the consultant.

With this new philosophy came a new name for the Society. Through its association with colonialism, the term “missionary” had acquired an unfavorable connotation, so that when the Society attempted to raise money from foundations and the business community, it found that the thrust of its work was largely misunderstood. Since its work was now heavily focused on renewal of the slum community and on an attack on the culture of poverty, the Society, on March 28, 1967, changed its name to the Community Renewal Society.

The Society lost no time in implementing the new guidelines, and moved toward fostering community organizations that would help and train others to conduct programs in urban mission. Before long the various settlement houses like Casa Central, the West Side Christian Parish, and the West Side Organization, which had been attracting other sources of funding, were spun off to become totally independent organizations with their own boards of directors. The agency which Time magazine had lauded in 1964 as “one of the nation’s liveliest and most progressive Protestant institutions” readied itself for a major new program.

In 1966, the Society’s board approved the concept of what would become known as the Toward Responsible Freedom program. This led to a proposal calling for a financial commitment of $2.8 million from individuals, corporations, churches, and foundations. This money would be used to support a five-year community-based project to help ghetto residents renew their neighborhoods. The emphasis would be on fostering community organizations, rehabilitating homes, improving education, training, health and welfare, raising earned income levels, and offering legal aid. It was a comprehensive renewal plan based on self-help by local residents, and $1.8 million of the targeted amount was eventually raised.

Some members of the Board of Directors had reservations about this “new” direction for the Society. But an examination of the Society’s record of commitment and programs revealed that while the emphasis of the plan was extraordinary, its purpose was not. The Society had always been involved in the ghetto, struggling with and for the poor. The unique aspect of the Toward Responsible Freedom program was its focus on one location, its provision for technical assistance, and the commitment by the Society to raise the money needed for the project.

Selection of the site--the Kenwood-Oakland area--followed consultation with the Black Caucus, comprising the heads of the major black community organizations. The City of Chicago expanded its designation of Model Cities areas to include the district.

As it turned out, the Ford Foundation, one of the major potential funders of the project, believed that community development efforts should be undertaken in conjunction with local government. On the other hand, some ghetto residents and some leaders of the Society and other organizations thought that the connection with city government could be more of a hindrance than a help in rebuilding communities. However, because of the Ford Foundation’s interest in the project, the Society agreed to expand its technical assistance to three additional areas designated by the City of Chicago as part of its Model Cities program.

The four areas named by the city were the Near South (including North Kenwood-Oakland), Mid-South (Woodlawn), West (North Lawndale), and North (Uptown). As such, these locations received special attention and aid from federal and local governments, as well as from other agencies. The Society developed its own Model Cities Technical Assistance Program.

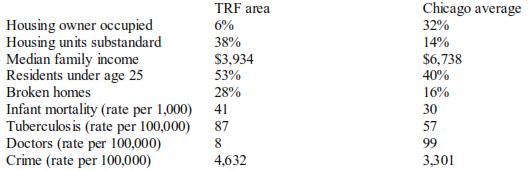

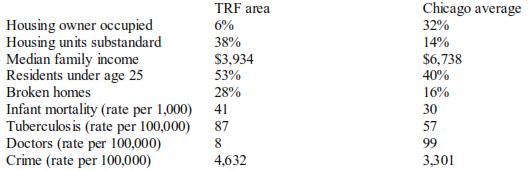

Encouraging maximum citizen participation, the Model Cities Technical Assistance Program was designed to serve as liaison between city and neighborhood in developing solutions to local problems and in assisting local neighborhood groups to acquire resources to develop their community_ The Society’s TRF program concentrated on one community organization in one location-the North Kenwood-Oakland area. As the following table shows, this district was one of the most depressed in the city.

The Near South Side TRF area was bounded by 35th Street on the north, Cottage Grove Avenue on the west, 48th Street on the south, and Lake Michigan on the east. Whereas in 1940 the area’s population had been 90 percent white, by 1968, 97 percent of the 49,000 in the 1.1-square-mile tract were black and 31.4 percent of the total population was on public assistance. There were 20,000 children under the age of 18 and no high school in the site area (though by the following year one was under construction). The community had five elementary schools, but had no hospital and no playgrounds (only five temporary playlots).

The Society directed its efforts to working with an already existing neighborhood group, the Kenwood-Oakland Community Organization (KOCO). A not-for-profit, tax-exempt organization, KOCO represented a coalition of various groups, organizations, and institutions in the community. On October 1, 1968, the Society and KOCO entered into a covenant by which KOCO committed itself to working with the Society for:

-improved quality and quantity of housing in the neighborhood;

-improved educational opportunities for all residents;

-development of cultural programs and recreational facilities;

-greater employment and economic development;

-unity and participation of residents in community affairs;

-justice and programs of legal assistance;

-meeting the health and medical needs of residents.

There were many obstacles to be overcome. In its search for sites where building or rehabilitation efforts could be undertaken, KOCO found that the Chicago Housing Authority (CHA) would divulge neither its plans for the TRF site area nor its holdings there. This necessitated time-consuming and expensive title searches. In addition, it turned out that many buildings were held by dummy corporations and many sites were held by the city’s Chicago Land Clearance Commission. KOCO was able, however, to become involved in the development of Lake Park Manor, a 164-unit apartment complex at Lake Park and 37th Street. This was the only subsidized apartment complex along Chicago’s entire lakefront in which units (34) were available for low-income families displaced by renewal efforts in the area.

KOCO created the True People’s Power Development Corporation (TPPDC) to foster economic development in the area. Renewal Builders Association Inc., was established by William Boya with the assistance of TPPDC, which retained 40 percent ownership. Renewal Builders Association’s largest and most successful effort was the rehabilitation of 48 units at 4612 S. Lake Park. It took eight months for the proposal to be approved by the Model Cities director, Mayor Daley, the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), and the Washington office of HUD. But once the $830,000 project was approved in April 1973, RBA trained many local residents in the building trades as it converted a gutted and boarded-up three-story building into usable housing. More than 100 men were taught construction skills during the three years of RBA’s existence.

In 1969, TPPDC formed the New Horizon Plastics Corporation. Molded plastic cups were the first products off the assembly line in March 1972. The 50,000-square-foot building at 4017 S. Wabash was larger than needed, but the 7-day-a-week, 24-hour-a-day operation fully utilized the two presses. By 1974 a contract from Kraft Foods for 4.5 million plastic margarine lids kept five presses busy full time. But overcapitalization, large utility bills, and above all, raw material shortages caused by the 1974-75 oil embargo presented many difficulties. The corporation’s financial problems mounted, New Horizon fell 90 days behind in payments to creditors, and the Small Business Administration closed the company in the fall of 1975.

KOCO attempted several projects in the health field, among them the Day Care Center for Mentally Retarded Children on 47th Street and the KOCO Mental Health Services at 1613 S. Michigan Avenue. In 1969, KOCO received a $30,000 planning grant from the Department of Health, Education and Welfare (HEW) and the Model Cities office. But the subsequent proposal for a comprehensive and badly needed health center was turned down because of objections by Model Cities and the Chicago Board of Health. In the fall of 1970 Model Cities announced its own plans for a health center at 43rd Street and Greenwood Avenue to be operated by the Board of Health. This center was eventually completed and, after a one-year delay for lack of operating funds, opened for service to the public.

In July 1971, the Mid-Southside Health Planning Organization obtained a $2.5 million grant from the Office of Economic Opportunity to establish a network of four Health Maintenance Organizations. KOCO was selected as one of the delegate agencies and received $517,000 to help organize Kenwood-Oakland Medical, Ltd. A new medical building for this program was completed at 501-525 East 43rd Street in 1974. The health center offered outpatient, maternity, and emergency care, as well as pharmaceuticals and laboratory and X-ray capabilities.

One of KOCO’s earliest and most successful programs was the Leadership Training Program funded by the Rockefeller Foundation. This effort helped residents understand what a community organization could and should be; provided information on community problems; and trained people to build and maintain a broadly based, viable community organization. The twelve-week intensive training course graduated 79 percent of the enrolled students, a total of 134 people, over a three-year period. A second program received a $200,000 grant from the Rockefeller Foundation to develop specialists in the seven areas of KOCO concern: housing, health, education, welfare, youth, law and justice, and economic development and employment. This training program, which focused intensively on issues and personal development, perhaps more than any other single KOCO activity helped create a true community of people where none had existed before. Graduates of the program went on to make important contributions to the work of KOCO as well as to other public and private agencies.

To raise the funds for the Toward Responsible Freedom activities and to conduct the various portions of the program, the Society hired new staff. Reverend S. Garry Oniki joined in 1967 as associate executive director for Planning and Research and directed the Model Cities Technical Assistance Program. He later became deputy executive director for the Society. The Reverend Reuben A. Sheares II, hired the same year, became associate director for Community Development and director of the Toward Responsible Freedom program. Thomas Keehn worked on foundation development and John Purdy, who had joined the Society in 1962, concentrated on board and fund development. These men contributed significant leadership and energy to the Society’s undertakings during this critical period.

The Society worked to develop KOCO as a model community organization, with neighborhood participation and leadership as key ingredients in that effort. Reverend Curtis E. Burrell, Jr., was elected head of KOCO late in 1967 and, once the Toward Responsible Freedom program was set in motion, worked with Sheares to draw KOCO into the TRF covenant and into economic development through creation of the True People’s Power Development Corporation.

In developing community participation, Burrell attempted to work with the gangs of the area. He helped engineer a shaky truce between two local gangs, the Black P. Stone Nation and the Disciples, and brought several Stone leaders onto the KOCO staff. The Black P. Stone Nation was a powerful gang with widespread influence, and many older residents did not think that the gang’s energies could be constructively channeled. Burrell felt he had to try. One of the alleged Stone leaders was Leonard B. Sengali, who became an executive organizer for KOCO in 1969. Sengali built a good reputation in the black community and was a visible and strong leader in KOCO.

In December 1969, Sengali was arrested and charged with the November 3, 1969, murder of a furniture salesman on the South Side. There were several irregularities in the prosecution’s handling of the case, and Sengali was released on bond and continued to work for KOCO. This incident generated strong negative reactions from board members, churches, and others who supported TRFI KOCO through the Community Renewal Society. In July 1970, after a hearing at which highly contradictory evidence was presented, the case was dismissed. Nevertheless, damage had been done not only to Sengali but also to KOCO and the Society.

On June 17, 1970, a month prior to the hearing, and amid charges that the Stones were using KOCO prestige to recruit youngsters for gang membership, Burrell had dismissed Stone members from his staff and closed the KOCO offices for several weeks. On June 29, nine bullets were fired into Burrell’s home while the family slept, and a few days later the Woodlawn Mennonite Church, of which Burrell was pastor, was also fired upon. On July 30, the church was gutted by a fire which had been deliberately set.

On July 27, 1970, in an article entitled “Chicago: Turning Against the Gangs,” Time magazine reported on the efforts of Burrell and disc jockey “Daddy-O” Daylie to gather community support in order to counter gang activity and influence. In the first six months of 1970 Chicago recorded 38 gang murders and 316 gang shootings, most on the South Side. Community pressure was successful in reducing overt gang activity, but KOCO did not overcome its leadership crisis for some time.

In April 1972, Robert 1. Lucas, who had been directing the Leadership Training Program since 1969, was elected chairman of KOCO and under his guidance the organization grew in strength and effectiveness. Throughout this difficult period, the Society never wavered in its support of KOCO and had been able to maintain its own fundraising efforts. In 1972 more than 80 percent of the corporations that had contributed to the Toward Responsible Freedom program in 1968 and 1969 were still supporting the second phase of that effort. More than $300,000 had been received from these donors for the TRF/KOCO program.

The issues of housing, leadership training, health, job skills, and community and personal welfare had been addressed and progress had been made in all of these areas. However, those who guided the programs had not been fully prepared for the complexity of the obstacles they encountered. There were formidable political and economic problems at the city and federal governmental levels, and within the community significant difficulty was experienced because of the interrelatedness of the problems and the high level of distrust among the various sectors of the community. And, as the final evaluation indicated, TRF “was never able to develop broadly based industrial and business financial support [because] business much preferred the safety of the Community Fund route to corporate responsibility.”{2}

The Society’s direct involvement with KOCO ended in 1974, although its Community Development Division continued to give aid to that effort. KOCO was by then receiving support from various organizations. It now receives funds from the United Way of Metropolitan Chicago.

The Society aided several other community organizations through its Model Cities Technical Assistance Program. In the Mid-South Model Cities areas, the Society helped The Woodlawn Organization develop its own land use and housing plan for its neighborhood. The plan set forth in general terms the type and quality of physical environment that the people of the community wanted to achieve. The published planning study set policy and design standards to guide future development in the area and laid the groundwork for the current community development achievements of The Woodlawn Organization.

In the West Model Cities Area, the Society worked with the North Lawndale Economic Development Corporation (now known as Pyramid West), the economic development arm of the Lawndale People’s Planning and Action Conference. It helped the North Lawndale Economic Development Corporation to participate in the federally sponsored Office of Economic Opportunity’s Special Impact Program. This enabled NLEDC to obtain capital and technical assistance to develop the neighborhood. The organization has built a nursing home; established a community bank; and rehabilitated housing which it manages. It also holds land for development.

Similarly, the Society worked with the Uptown Area Peoples’ Coalition in the North Model Cities Area to develop a planning study on land use in the neighborhood. This study provided a planning framework for the organization and the residents of the community. Subsequently formed organizations have built on the approaches to community planning carried out in the Society’s work in the Model Cities areas.

The Society aided and was involved with several other community organizations through its Community Development Division. One of these was the Organization for a Better Austin (OBA), a neighborhood-based group seeking citizen involvement in developing a better community. Unknown to the Society and OBA was the fact that Marcus Salone, the OBA executive director, was a police informer. Shortly after this was made public by the press, the Chicago Sun-Times printed a portion of a police surveillance report on the Black Strategy Center which erroneously stated that the Society was directly connected to the Center and sought to bring about a “revolution in the United States,” with the implication that this revolution was to be violent.

In October 1975, highly concerned about this evidence of police surveillance and about the damage done to the Society’s reputation, the Society’s board, together with several other organizations, joined in an American Civil Liberties Union suit to expose, stop, and collect damages for police spying on their activities. The lawsuit was successful at least in accomplishing its first objective. On Sunday, June 10, 1977, the Chicago Tribune published a major feature article with the first of four reports detailing the scope and nature of the police department’s activity. Two reporters had “pored over thousands of page