Human Evolution

The human lineage diverged from that of apes about 7 million years ago, or maybe even earlier. When their complete genomes were compared in 2005, the two species were found to share 98% of their DNA. The differences served as a molecular clock to estimate the rate, at which new genetic mutations were acquired over generations. The human evolution is characterised by a number of morphological, physiological and behavioural changes, that have taken place since the split between the last common ancestor of humans and chimpanzees. However, Rudolph Zallinger’s ‘March of progress’, the iconic image with the walking figures moving from chimp to upright human, contains some common misconceptions. One is, that there was a linear progression from more primitive to more advanced forms, where the modern human represents the zenith of evolution. Another is, that only one species or type of early hominin existed at any given time. But that is not the case. The best way to comprehend evolution, is to imagine the branches of a bush, where the outside edges are the lineages evolved from earlier ones still around today, while the lower branches are extinct species. Some of those are part of the same overall lineage, that led to us, hence our ancestors, and some others are branches near ours, which ended, before they reached the top of the bush, making them our evolutionary cousins.

The picture, emerging from a large amount of data sources, that include more detailed analyses of Earth’s complex orbit and other astronomical cycles, as well as of dust, lakes, volcanoes, tectonic plates and types of animals, is that human ancestors lived in many varied environments and climates, wetness and dryness, stability and rapid change, and shows, that many different groups evolved and mingled over a period of millions of years, developing human characteristics at different rates. They were very flexible in their behaviour based on the diversity of the environments, they found themselves in, and so was also their diet, adaptable and variable using many plants and meat, depending on the availability of resources. They managed to use knowledge of these diversified environments in order to expand their reach and live longer. These changes triggered the need to learn new techniques and to somehow preserve social connections in this flux, which put pressure on the plasticity of the nervous system. That translates into pressure to increase the brain size. The discoveries present many distinct groups, that had variant sizes of body, brain and teeth. The changes in teeth allowed eating of tougher plant products and animal meat, which led to develop more and better tools to prepare these diverse meals. Tools were actually carried for long distances, attesting to their great value. The types of food influenced the body size. Larger size occurs, when there is stability and easiness in the resources, when meat is prominent food and when there is less risk of death from predators or microbes. Sufficient amount of high quality food favours also the increase in the size of the brain, as it requires more energy. That means at the same time, that the gut and the legs have to be more efficient to consume less energy.

The methods of discovering, what happened in the past, are based on findings of artefacts and fossils, as well as on genetic studies, very arduous and difficult tasks, as scientists estimate, that one million years ago there were in total 20.000 - 50.000 human ancestors on earth. Yet remarkable discoveries continue to occur and dazzle the world. A 6-7 million years old skull has been found in Chad with an ape-like face, human style brain and small canine teeth, which is the earliest found specimen, that lies on our lineage or not far from it. Markings on animal bones from 3.4 million years ago were discovered in Ethiopia, advanced flaked tools from 2.6 million years ago for meat stripping appeared in Africa and bifacial stones from 1.7 million years ago surfaced in Kenya. Another evidence showed modern middle ear bones 3 million years ago, which implies communication, modern shoulders 2 million years ago, which allowed accurate throwing of spears, modern hand 1.7 million years ago, that could use advanced tools and a nearly modern foot 1 million years ago. Discoveries on Flores Island near Indonesia showed human ancestors from 1.1 million years ago, which proves they could travel from Africa at sea, a very challenging task, as it included building boats or rafts, navigating rough seas and surviving in a new land. At the same time findings in South Africa proved, that humans had learned the controlled use of fire.

Furthermore, newly discovered human fossils are outgrowing the family tree with great frequency. Australopithecus deyiremeda, a brand new and previously unsuspected species, was discovered in Ethiopia dating back to 3.5 - 3.3 million years ago, that lived at the same time as one of our potential ancestors, ‘Lucy’, Australopithecus afarensis; Australopithecus sediba, a nearly 2 million years old relative from South Africa with apelike and humanlike traits, which most likely represents a transitionary phase between the genus Australopithecus and the genus Homo. Also discovered in South Africa, Homo naledi, lived much more recently, around 335.000 years ago, which means it may have overlapped with homo sapiens and had a mix of primitive and modern features, such as small brain case, about onethird the size of Homo sapiens and a large body weighing approximately 50 kilos. Homo floresiensis, a tiny 1.1 m height, small-brained hominin, who first appeared on the Indonesian island of Flores about 95.000 years ago, Homo luzonensis, another extinct species unearthed in Philippines, who lived in the island of Luzon at least 50.000 - 67.000 years ago with a mixture of physical features present in very ancient human ancestors and in more recent people, the Denisovans, an archaic population of humans discovered in the Altai mountains in Siberia, who contributed 3 to 5 percent of their genetic material to Aboriginal Australians and New Guineans, as well as a gene to the Tibetans, that helps them survive high-altitude environments, and many more.

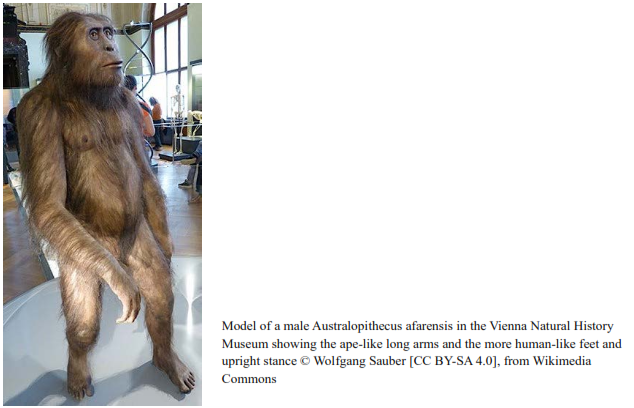

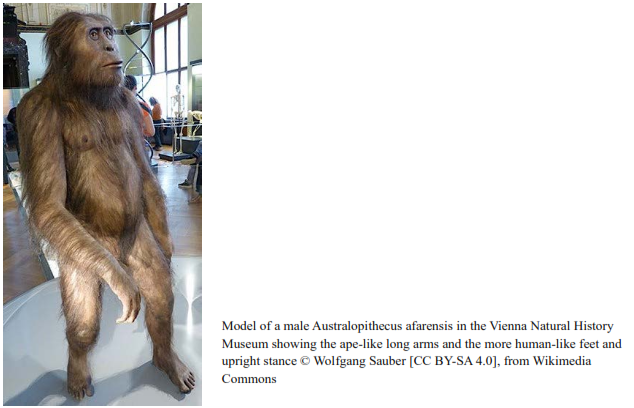

The distinctive mark of hominins is generally considered to be upright land locomotion on two legs. Though they were indeed bipedal when on the ground, there are important structural features in their anatomy, that show they walked differently from the way modern humans do. They also retained many reminders of their ancestry like the rather long arms, short legs, narrow shoulders and long grasping extremities. The environments in which these early hominins lived, suggest, that they were still comfortable in the forests and at the same time they were largely active in the woodlands, where the forests graded into more open savannas, probably a result of climate changes. The hundreds of fossils findings have cemented Africa as the cradle of humankind. But with dramatic climate changes it is impossible to consider one particular environment critical for human evolution. Furthermore, recent fossil discoveries are altering notions of where this evolution took place. There is now evidence, that ancestors might have migrated out of Africa to Eurasia and then migrated back 2 million years ago.

Australopithecus afarensis lived between 3.9 and 2.9 million years ago in Africa and was about 1.1 - 1.5 m tall and 27 - 42 kilos. The morphology of the scapula appears to be ape-like, the canines and molars are reduced, the face has forwarded projecting jaws and the brain size is relatively small, 380 - 430 cm3. Some studies suggest, that A. afarensis was almost exclusively bipedal with arches, that helped movement, while others propose, that was partly arboreal.

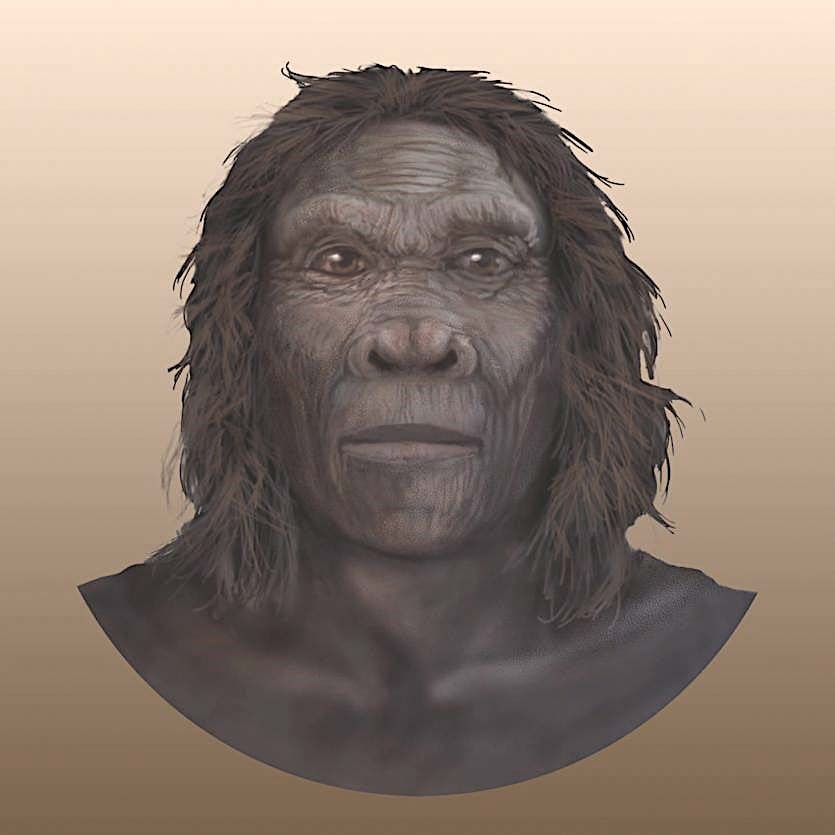

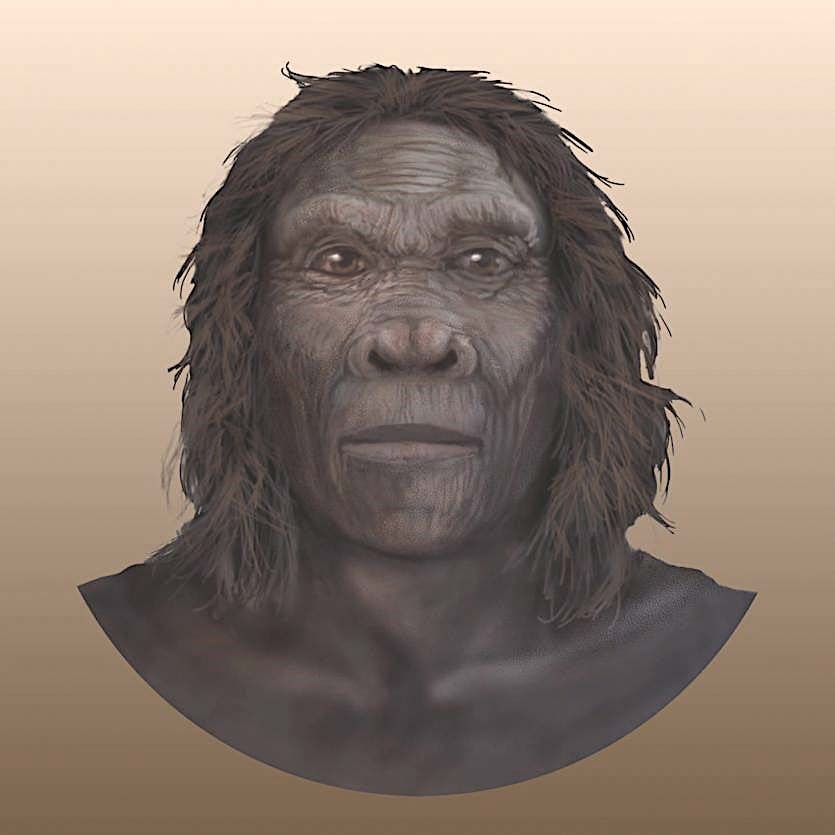

The boundary, for when our ancestors are considered to count as human, is quite unclear, but scientists place the starting point at species, that emerged about 2.4 million years ago. We are the sole survivors of this group, but our planet was once home to a surprising diversity of humans. The earliest documented representative of the genus Homo is Homo Habilis, who lived in Africa between 2.4 and 1.4 million years ago. The name means ‘handyman’, as was originally thought to be the first maker of stone tools. He was between 1 - 1.4 m tall and 32 kilos, had a larger braincase and smaller face and teeth, than the Australopithecus, but retained some ape-like characteristics like long arms and a moderately protruding face. His brain was about 50% bigger than that of the Australopithecus, but still half as big as a modern human’s. Although a scavenger rather than a master hunter, he utilised stone flakes to make tool sets, that offered the much-needed edge, to prosper in hostile habitats previously too formidable for primates.

Homo habilis, face illustration, Smithsonian Institution.

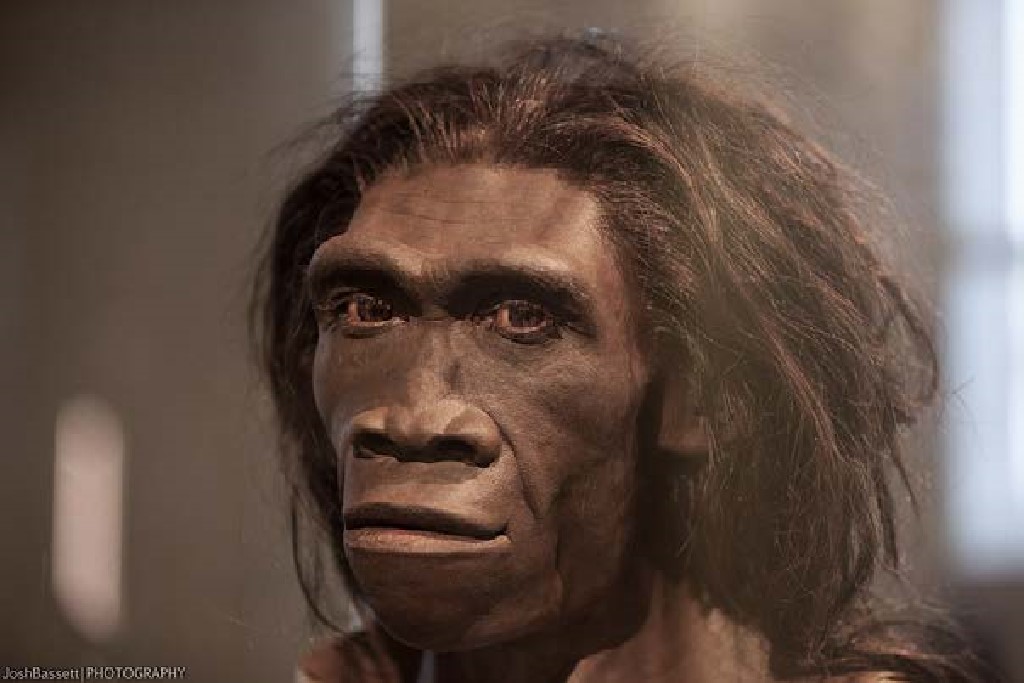

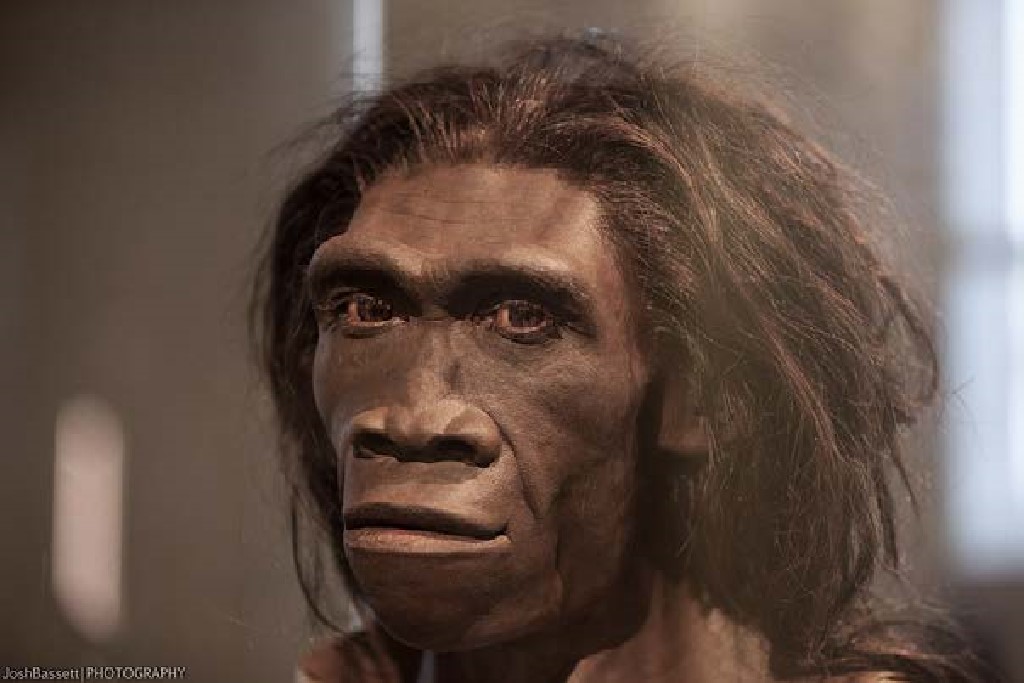

About 1.9 million years ago Homo erectus appeared, who was much closer to modern humans anatomically with shorter arms and longer legs. These characteristics are considered adaptations to a life on the ground indicating the loss of the tree climbing ability. He was 1.5 - 1.9 m tall and up to 70 kilos weight with a smaller jaw and teeth. It is believed, that he was the first to use complex tools and to master fire, which provided protection against predators and reduced mortality rates. Complex spears were recently found in South Africa, that were put together with multiple parts dated 500.000 years ago. His body and brain size required a lot of energy on a regular basis to function. According to one theory the invention of cooking and the consumption of meat and other types of protein allowed more efficient foraging and digestion, freeing up energy, which fuelled the evolution of the brain. The cranial capacity doubled to 800 - 1100 cm3. This species was the first to spread in an impressive geographical range with fossils found in Africa, Spain, Italy, China and thanks to a land bridge during a glaciated era, in Indonesia, where the species persisted longest. Homo erectus was a very successful early human surviving earth’s changing environments for nearly two million years, almost six times longer, than modern human has been around. The youngest known fossils were identified on the Indonesian island, Java, where a dozen skulls found before WW II have been dated to about 110.000 years ago. The species survived for so long, that they ended up sharing the planet with new groups of humans, such as the Neanderthals, possibly Homo floresiensis in Indonesia and Homo sapiens, while at the beginning of its time Homo erectus coexisted with several others including Homo rudolfensis, Homo habilis and Paranthropus boisei. Sometimes they were even discovered at the same excavation sites. Though Homo erectus did finally fade away, most probably due to climate change, it will always remain one of the iconic and prominent species in the family tree of human ancestors.

Homo erectus, reconstruction by John Gurche.

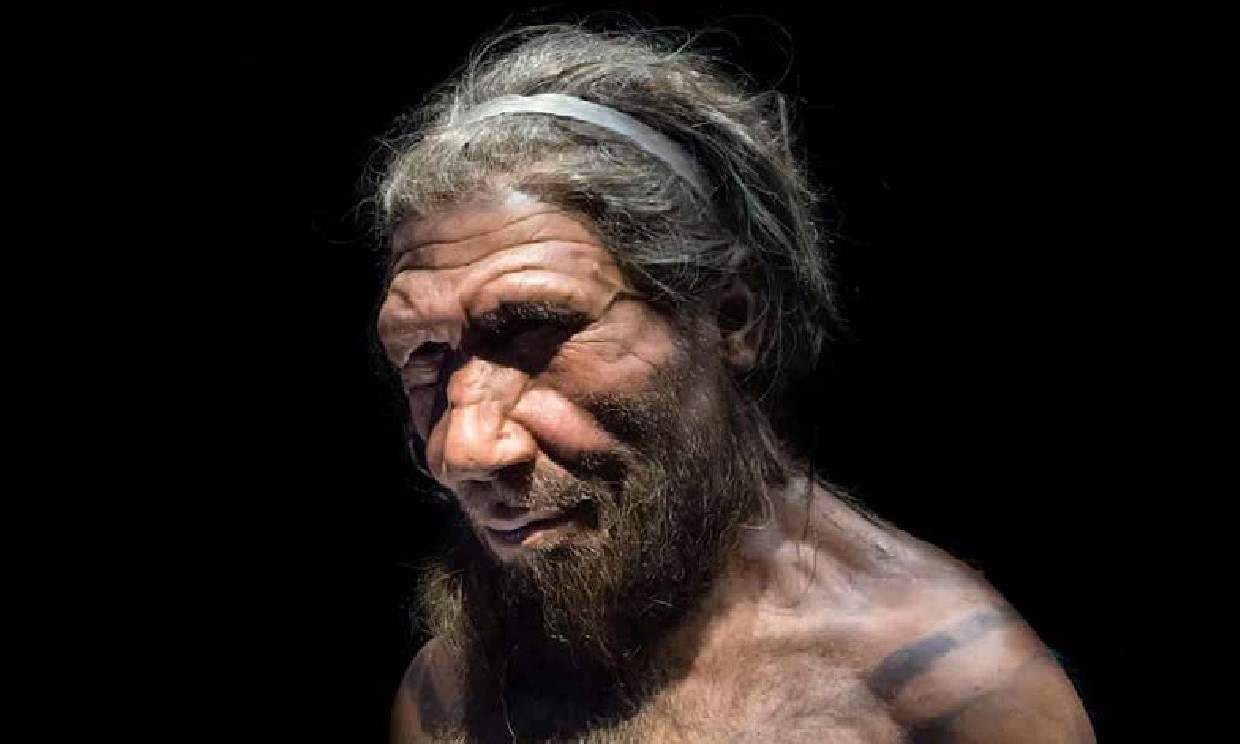

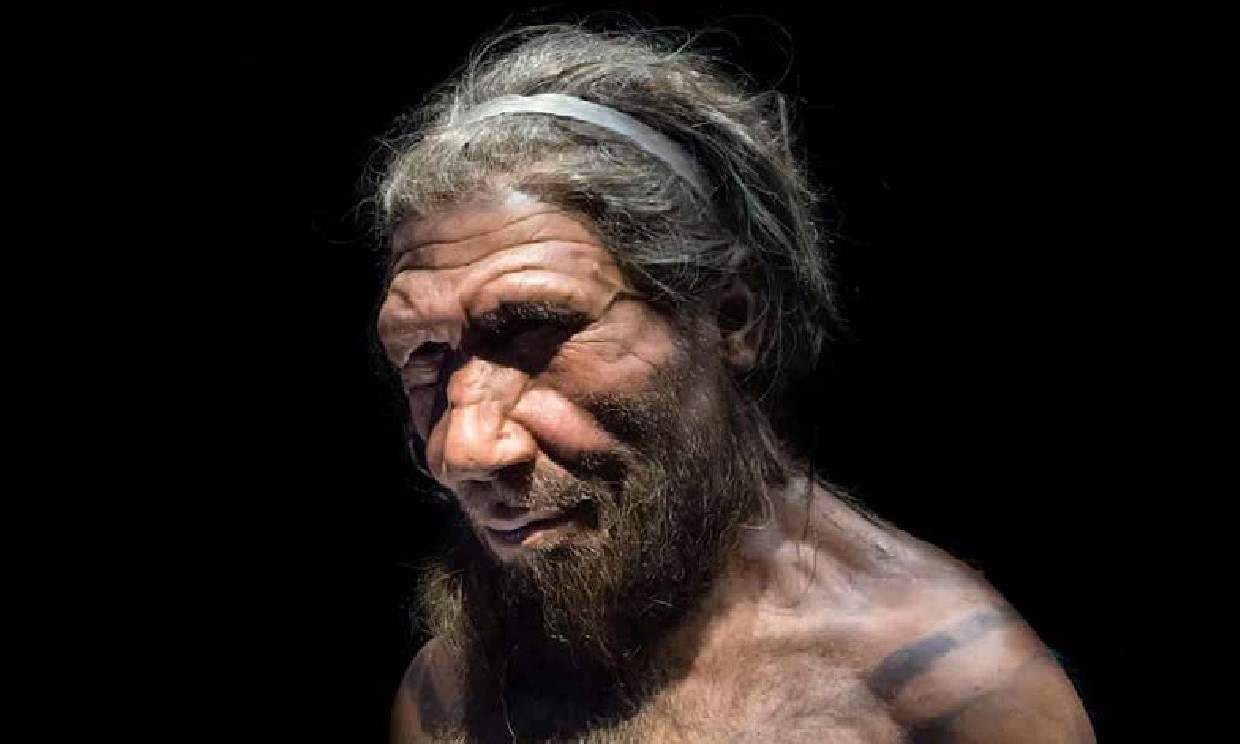

350.000 years ago, the Neanderthals lived in Europe and Asia. While it was believed, that they were cognitively inferior, they were able to make engraved patterns on iron oxide, red ochre paintings of abstract animal figures and handprints indicating ability for symbolic thought, bone awls, hide clothing, shell beads, a special birch bark glue to fasten stone to wood handles, showing chemical knowledge, and stone tipped javelins. They invented also the string 90.000 years ago, while they kept very neat and organised houses, they buried their dead marking occasionally the graves with offerings and they cared for their sick and injured. Evidence from DNA indicates, that no significant gene flow occurred between them and Homo sapiens. They were rather two separate species, that shared a common ancestor about 660.000 years ago. But they did indeed interbreed. Nearly all modern non-African humans have 1% - 4% of their DNA derived from Neanderthal DNA. Interbreeding with these ancient humans allowed Homo sapiens to acquire genes, that improved its chances of survival. Some of the DNA inherited from Neanderthals seems to have been involved in boosting immunity for example. Around 40.000 years ago the Neanderthals went into a steep decline, at a time when Homo sapiens were settled in Eurasia. Perhaps they were struggling to compete for resources, they were killed in conflicts or were less well adapted to changes, that took place.

Scientifically accurate reconstruction of a Neanderthal, Natural History Museum in London.

The earliest fossils of anatomically modern humans are about 300.000 years old, excavated from a cave in Morocco, where a partial skull and lower jaw remains, stone tools and evidence of fire was found, while up till recently previously findings were pointing to south and east Africa 100.000 years later. Nexus of populations spring up all over Africa and studies show a really strong one around 200.000 years ago, which has genetically survived in today’s population, but definitely there will be others. Modern humans didn’t originate from any one place, but multiple groups shaped, who we are today, while the entire African continent could be the birthplace of our species. As they spread out of Africa, they encountered other hominins replacing them either through competition or through hybridisation. That is, when modern humans began colonising the world. They arrived in Greece 210.000 years ago, as indicates a skull finding, that belongs to the oldest modern human discovered outside Africa, predating what researchers previously considered to be the earliest evidence of Homo sapiens in Europe by more than 160.000 years, they reached Crete 170.000 years ago and other Greek islands 110.000 years ago, as findings of hand axes, tetrahedral picks and cleavers show, they entered Asia about 100.000 years ago, they arrived in Australia about 65.000 years ago and accessed the Americas by at least 14.500 years ago. The last frontier was Antarctica, where humans have maintained a presence only since the 19th century.

Compared to late archaic humans, modern humans generally have more delicate skeletons. The faces are also smaller with much less, if any, of the distinct brow ridges and prognathism of other early humans and the jaws are less heavily developed, with smaller teeth and pointed chins. The Homo sapiens developed also a much larger brain, typically 1350 cm3, which has 100 billion neurons. Housing such a big brain involved a reorganisation of the skull into a thin-walled, high vaulted one with a flat and near vertical forehead. The increase in volume overtime has affected areas within the brain unequally. The temporal lobes, which contain centres for language processing, have increased disproportionately, as has the prefrontal cortex, which has been related to complex decision making and moderating social behaviour and the cerebellum, which has been associated with balance fine motor control and recently speech and cognition.

Throughout the history there was a tendency for new hominins to acquire ever larger brain. This increase has come at a cost, not only because brain tissue expends significant amount of energy, but also because there is a conflict between brain size and bipedalism. It is possible, that bipedalism was favoured, because it freed the hands for reaching and carrying food, saved energy during locomotion compared to a quadrupedal knuckle - walking, enabled long distance running and hunting, and provided an enhanced field of vision. All very advantageous features for thriving. Anatomically the evolution of bipedalism has caused a large number of skeletal changes. The most important occurred in the pelvic region in order to keep the centre of gravity stable while walking. The drawback is, that the birth canal had to be smaller, enough though to permit the passage of the new-born. That effected significantly the process of human birth, which is more difficult than in other primates. The foetal head must be in a transverse during entry into the birth canal and rotate about 90 degrees upon exit. The smaller birth canal is a limiting factor to our brain size, which prompted a shorter gestation period leading to the relative immaturity of the human offspring compared to other primates. The increased brain growth after birth had a big effect on humans’ life, as the children are depended on their mothers for longer time. The postnatal brain growth allows for extended periods of social learning and language acquisition in juvenile humans.

It is not obvious, why natural selection would have favoured the brain’s dramatic expansion given the costs. Although the human brain is only about 2% of total body weight, it uses about 20% of the total calorie intake. Not to mention the danger and the complications during birth. Nevertheless, it did happen, humans got equipped with such an incredible complexed organ and they took a huge step forward.