CHAPTER 3

Bronze Age

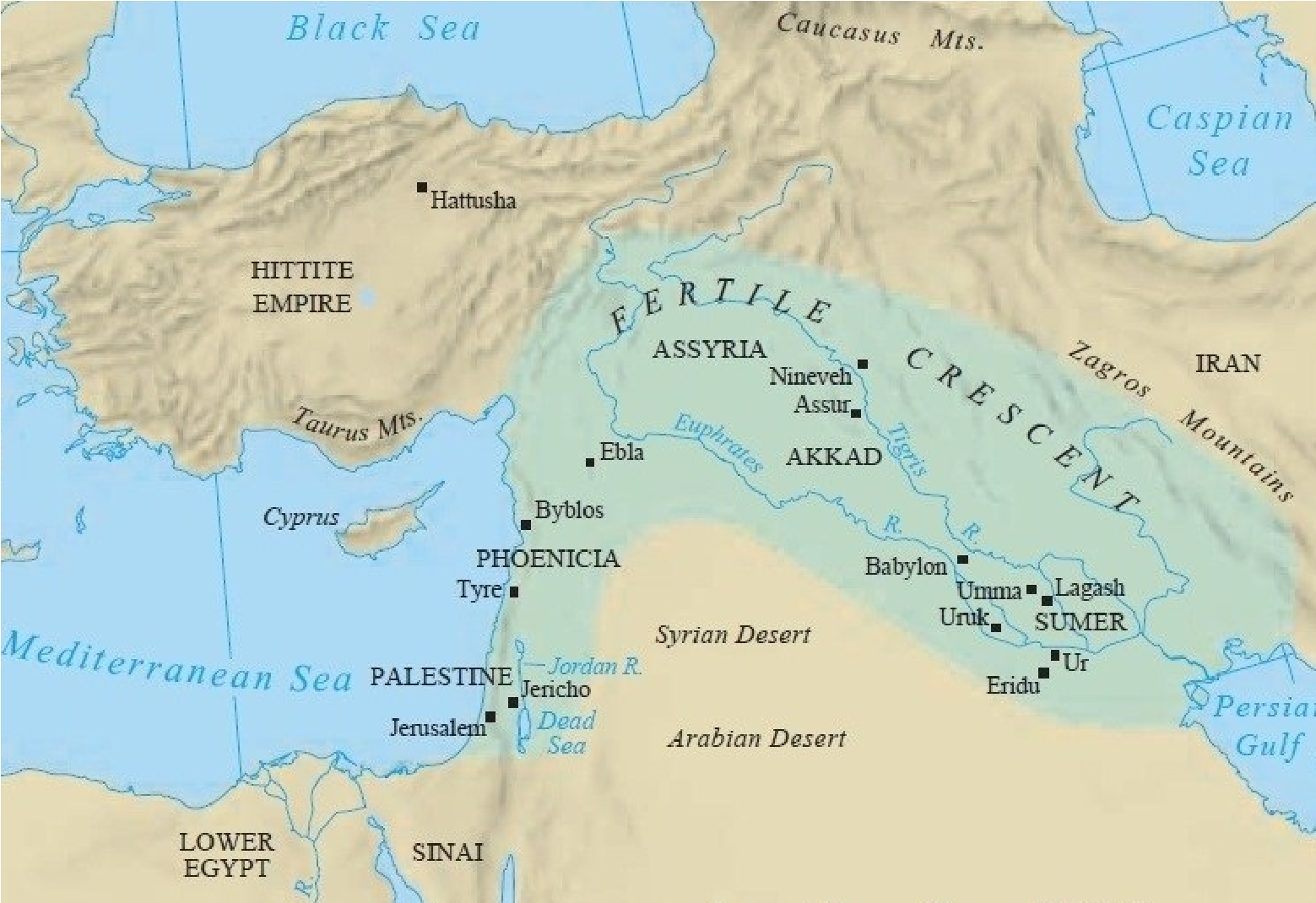

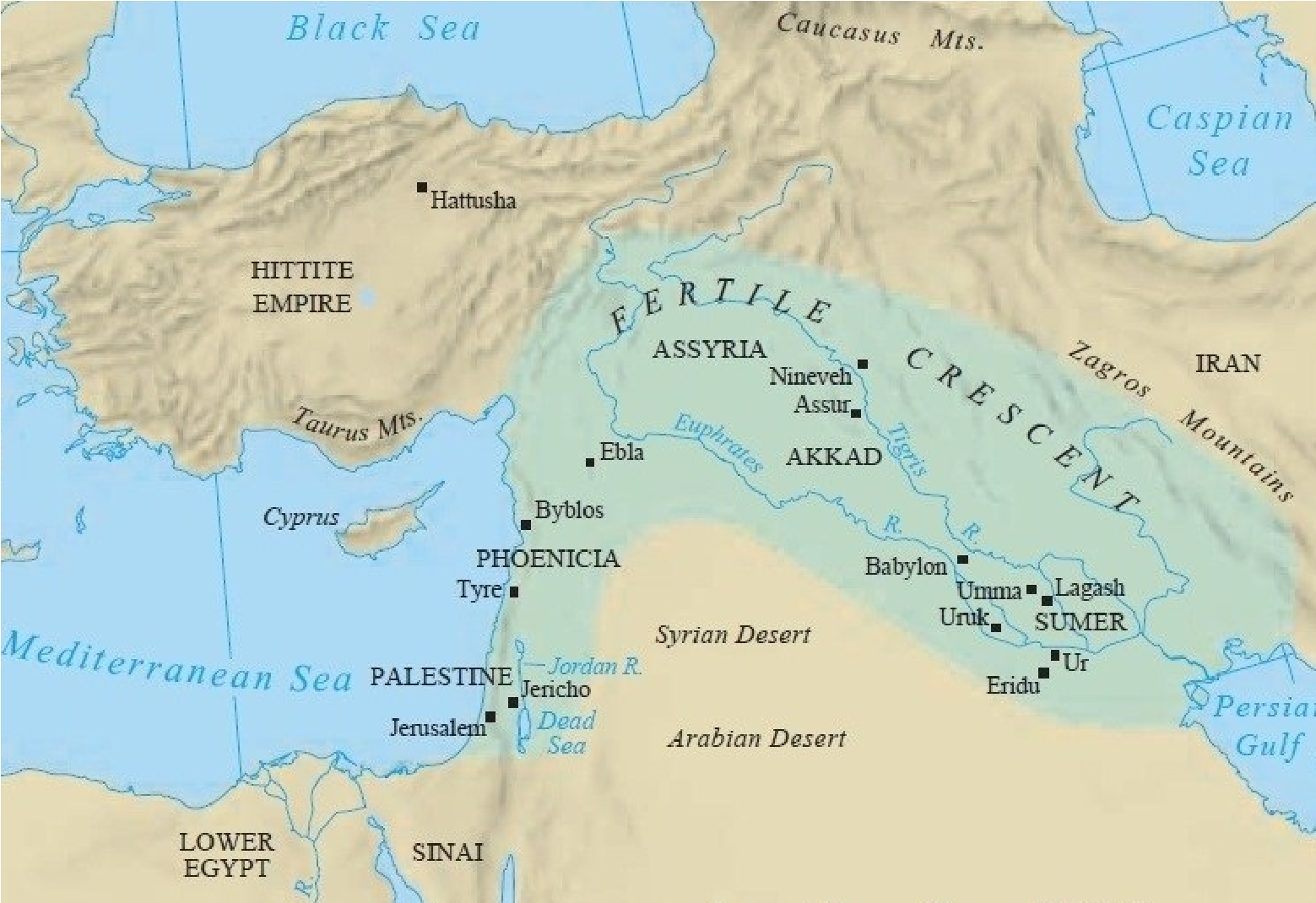

Around 6000 B.c., after the agricultural revolution had spread from its place of origin on the Fertile Crescent of the rivers Tigris and Euphrates, Neolithic farmers started filtering into the Fertile Crescent itself. In the ancient days it was known as Mesopotamia, which derived from the Greek language and literally means between the rivers. Around 3500 - 3100 B.c. the foundations were laid for a new economically and socially organised society, significantly different from anything previously known. This far more complex culture, based on large urban centres rather than simple villages, is what we associate with civilisation. By discovering how to use metals to make tools and weapons, late Neolithic people effected a revolution nearly as far reaching as the previous, shaped by the agriculture. Neolithic artisans discovered how to extract copper from oxide ores by heating them with charcoal and how to improve it by adding tin. The resulting alloy, bronze, was harder than copper and provided a sharper cutting edge. The advent of civilisation in Sumer is associated with the beginning of the Bronze Age, a period where the most advanced metalworking uses bronze either based on the local production or on trade with other areas. The time of introduction and development of bronze technology was not synchronous universally. The Bronze age lasted until about 1200 B.c., at least in the most developed areas, when iron weapons and tools began to replace those made of bronze marking the transition to the Iron Age.

(quangcaorongviet.com)

MESOPOTAMIA

Sumer

Each year the two great rivers of Mesopotamia were swollen, after the winter snows of the northern mountains were melted and each year at flood stage they spread a thick layer of immensely fertile silt. Consequently, the delta of the two rivers was a land of swamp rich in fish, wildlife and date palms. And it was here, between 3500 and 3000 B.c. that agricultural settlers created the rich cities of Sumer like Eridu, which is considered to have been the world’s first city, Ur, Uruk etc. The delta could only be made habitable by large scale irrigation and flood control, which was managed first by a priestly class and then by godlike kings. The layout and clearing of the canals required expert planning, while the division of the irrigated land, the water and the crops demanded political control.

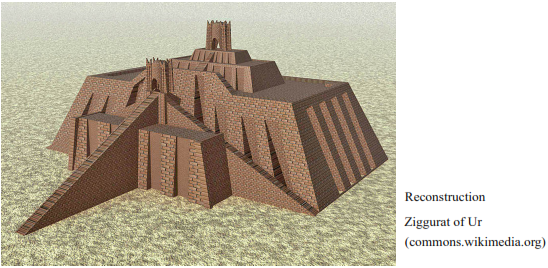

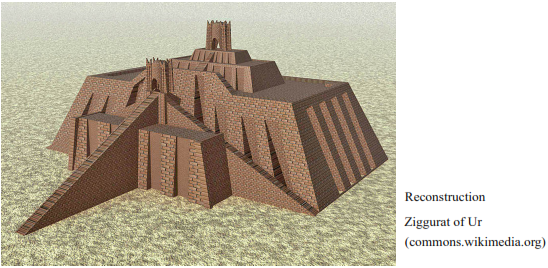

By 3000 B.c. the Sumerians had solved this problem by forming communities around their Ziggurats - Temples, where the gods visited earth and the priests climbed to its top to worship, while the very same priest-bureaucrats controlled the political and economic life of the city in the name of the city gods, including Anu the sky god, Enlil the lord of storms and Ishtar the morning and evening star. According to the epic literature that was composed, the mortals were created to enable the gods to give up working. The three most impressive survivals are the story of the creation, the flood, which parallels in many details the biblical story of Noah, and the story of Gilgamesh, the classic hero of Mesopotamian literature, who was pressing the gods in vain for the secret of immortality.

After 3000 B.c. the growing warfare among the cities made military leadership vital. The head of the army became king and assumed an intermediate position between the god, whose agent he was, and the priestly class. Thus, king and priests represented the upper class in a hierarchical society. Below them were the scribes, the secular attendants of the temple, who supervised every aspect of the city’s economic life and developed a rough judicial system. Outside the temple officials, society was divided between an elite of large landowners, military leaders, a heterogeneous group of merchants, artisans and craftsmen, free peasants, who composed the majority of the population, and slaves.

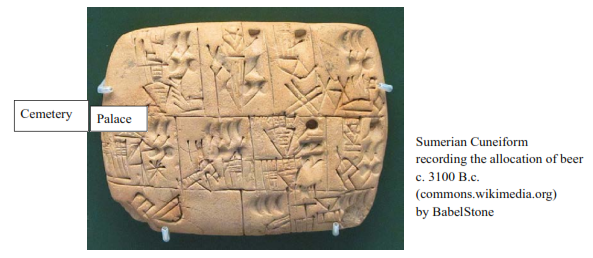

Thousands of tablets have been found in the temple compounds proving, that the bureaucrats of Sumer had developed a complex commercial system including contracts, grants of credit, loans with interest and business partnerships. Moreover, the planning of the vast public works under their control led the priests to develop a useful mathematical notation, including both a decimal notation and a system based upon 60, which has given us our sixty-second minute, our sixty-minute hour and our division of the circle into 360 degrees. They invented mathematical tables and used quadratic equations. Both for religious and agricultural purposes, they studied the heavens and they created a lunar calendar with a day of 24 hours and a week of seven days.

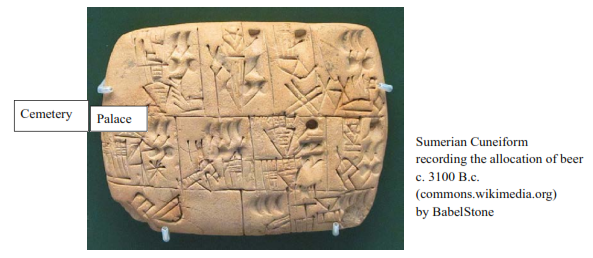

The earliest writing of the Sumerians was picture writing similar in some ways to Egyptian hieroglyphs. They began to develop their special style, when they found that on soft, wet clay it was easier to impress a line than to scratch it. To draw the pictures, they used a stylus. Pictures later lost their form and became stylised symbols. This kind of writing on clay is called cuneiform, from the Latin cuneus, meaning ‘wedge’. Cuneiform was difficult to learn. To master it, children usually went to a temple school. Using a clay tablet as a textbook, the teacher wrote on the left-hand side and the pupil copied the model on the right. Thousands of groups had to be mastered. The pupils also studied arithmetic.

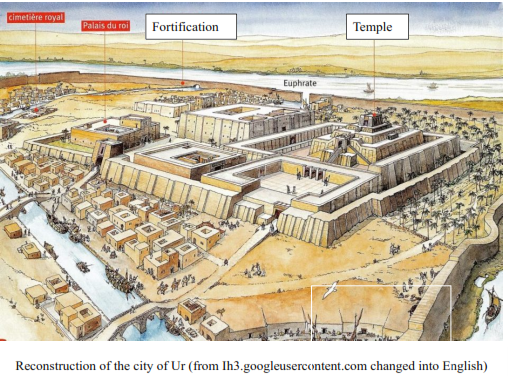

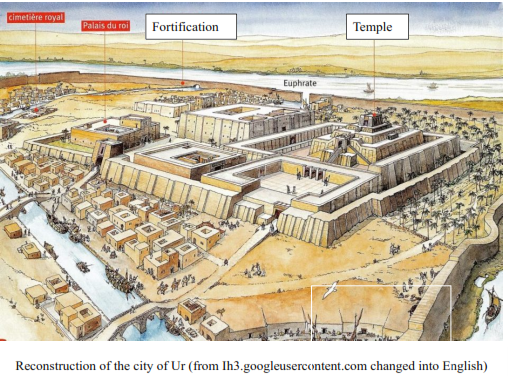

The cities in Sumer differed from primitive farming settlements. They were not composed of family owned farms, but they were ringed by large tracts of land. These tracts were thought to be owned by the local god. A priest organised work groups of farmers to tend the land and provided barley, beans, wheat, olives, grapes and flax for the community. All of the Sumerian cities were built beside rivers, either on the Tigris or Euphrates or on one of their tributaries. The city rose, inside its brown brick walls, amid well-watered gardens and pastures won from the swamps. In all directions the high levees of the irrigation canals led to grain and vegetable fields. The trading class lived and worked in the harbour area, where the river boats brought such goods as stone, copper and timber from the north.

Most citizens lived within the walls in small, one-story houses constructed along narrow alleyways, which were provided with a door, that turned on a hinge and could be opened with a sort of key. The city gate was on a larger scale and seems to have been double. The more elaborate homes were colonnaded and built around an inner courtyard. By far the most impressive section of the city was the temple compound, which was surrounded by its own wall. Here were the workshops and homes of large numbers of temple craftsmen, such as jewellers, carpenters and weavers, the offices and schoolrooms of the scribes, as well as the commercial and legal offices of the bureaucrat priests.

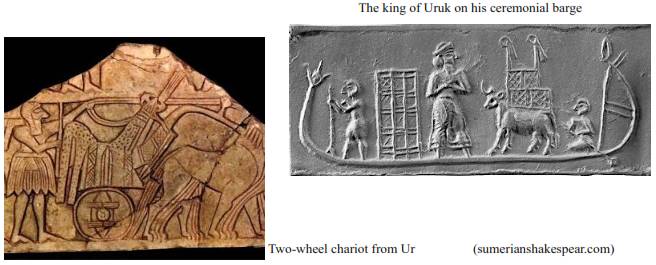

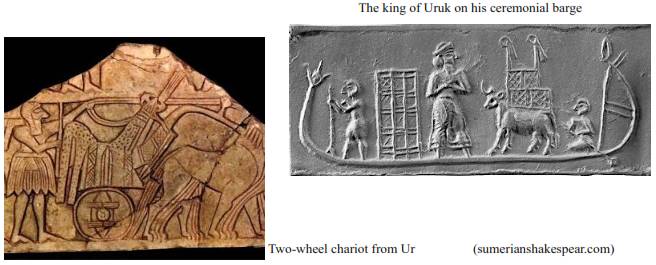

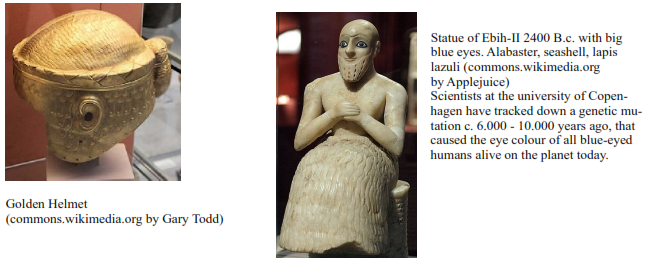

Near the temple was located the king’s palace and graveyard, where an increasingly lavish form of ceremonial life was organised, as the kings gained greater control over the city’s surplus. When archaeologists uncovered the royal graves, they discovered not only elaborate golden daggers, headdresses of gold, lapis lazuli, fantastically worked heads of bulls, harps and lyres, sledges and chariots, but also lines of elegantly costumed skeletons laid carefully in rows. In a gigantic mass suicide, probably through the drinking of a drug, the king’s courtiers and some of his soldiers had followed their master to his afterlife journey.

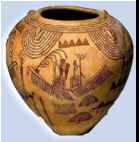

In Samuel Noah Kramer’s book, ‘History Begins at Sumer’, he lists 39 ‘firsts’ in history from the region, among which are the first schools, the first proverbs and sayings, the first messiahs, the first Noah and flood stories, the first love song, the first aquarium, the first legal precedents in court cases, the first tale of a dying and resurrected god, the first funeral chants, first biblical parallels and first moral ideas. The Sumerians not only invented time, based on their sexagesimal system of counting creating the 60-second minute and the 60-minute hour, but they also divided the night and day into periods of 12 hours, set a limit on a work day with a time for beginning and ending and established the concept of days off for holidays. The Sumerians may have also invented military formations and introduced the basic divisions between infantry, cavalry and archers. They developed the first known codified legal and administrative systems, complete with courts, jails and government records. The plough was also invented in Sumer, the first one was probably a stick pulled through the soil with a rope. In time, domesticated cattle were harnessed to drag the plough in place of the farmer. As a result, farming advanced from the cultivation of small plots to the tilling of extensive fields. Another important invention was the potter’s wheel, first used in Sumer soon after 3500 B.c. Earlier people had fashioned pots by moulding or coiling clay by hand, but now a symmetrical product could be produced in a much shorter time. The potter’s wheel has been called the first really mechanical device. Pottery was plentiful and the forms of the vases, bowls and dishes were manifold. There were special jars for honey, butter, oil and wine, which was probably made from dates. Some of the vases had pointed feet and stood on stands with crossed legs. Others had a flat bottom and were set on square or rectangular frames of wood. The oil-jars and probably others were sealed with clay. Vases and dishes of stone were made in imitation of those of clay.

Ceramic Vessel (faculty.ucr.edu)

A bit later wheeled vehicles appear in the form of ass-drawn war chariots. For the transport of goods overland, however, people continued to rely on the pack ass. Oxen pulled the carts and ploughs, while donkeys served as pack animals. Bulky goods were moved by boat on the rivers and canals. The boats were usually hauled from the banks, but sails also were in use. As mud, clay and reeds were the only materials the Sumerians had in abundance, trade was necessary to supply the city workers with materials. Merchants went out in overland caravans or in ships to exchange the products of Sumerian industry for wood, stone and metals. There are indications that Sumerian sailing vessels even reached the valley of the Hindus River in India.

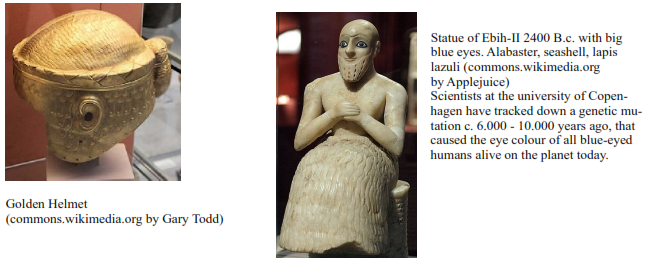

The Sumerians were great creators and their art attests to that. Sumerian artefacts depict elaborate detail and ornamentation with fine semi-precious stones imported from other lands, such as lapis lazuli, marble, alabaster and precious metals like gold incorporated in the design. Stone was rare, therefore it was reserved for sculpture, while clay was the most common material.

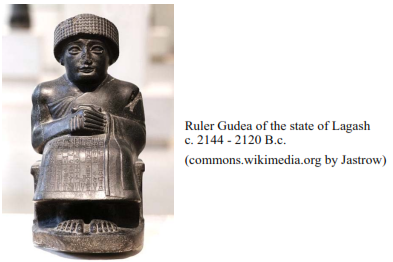

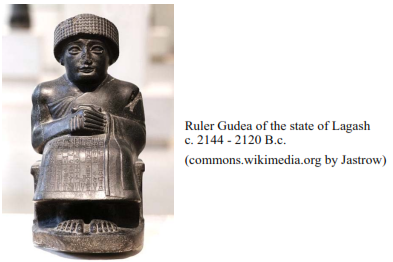

With the development and growth of the cities of Sumer conflicts arose among them. They fought for control of arable land and of the Tigris and Euphrates for transportation and irrigation, they faced boundary disputes and debates in their attempts to acquire luxury goods, and all that until the rise of the First Dynasty of Lagash in 2500 Bc. Under the king Eannutum, Lagash became the centre of a small empire, which included most of Sumer. In addition, his realm extended to parts of Elam, a region located in what is now south-west Iran, and along the Persian Gulf. He seems to have used terror as a matter of policy.

In 2234 B.c. a young man, who later claimed to have been the king’s gardener, seized the throne. This was Sargon of Akkad, who founded the Akkadian Empire, the first multi-national empire in the world. The Akkadian Empire ruled over the majority of Mesopotamia, including Sumer, until a people known as the Gutians invaded from the north, an area of modern-day Iran, and destroyed the major cities. The Gutian Period (c. 2218 - 2047 B.c.) is considered a dark age in Sumerian history and the Gutians a punishment sent by the gods. It got even worse, when the Amorites showed up.

The Amorites were a Semitic people who seem to have emerged from western Mesopotamia, as does their name Amorite means, westerners or those of the west. Their origins are unknown. They first appear in history as nomads, who regularly made incursions from the west into established territories and kingdoms. The Babylonian literature describes them in negative terms, as they threatened the stability of established communities living off the land and taking, what was needed from the communities they encountered. King Shulgi of the city of Ur constructed a wall 250 km long specifically to keep them out of Sumer. Amorite’s invasions undermined the stability and trade of the cities and led to the weakening of Ur and Sumer as a whole, which encouraged Elam, to mount an attack and break through the wall. The sack of Ur by the Elamites in 1750 B.c. ended Sumerian civilisation.

Babylonia

Following the fall of Ur many Sumerians migrated north, while the Amorites merged with the Sumerian population in southern Mesopotamia and ruled in the region until the rise of Hammurabi and the Babylonians.

Babylon, ‘Gate of God’, is the most famous city from ancient Mesopotamia, whose ruins lie in modern-day Iraq 94 km south-west of Baghdad. The city is known for its impressive walls and buildings, its reputation as a great seat of learning and culture, and for the Hanging Gardens, which were man-made terraces of flora and fauna and were cited by the Greek historian Herodotus as one of the Seven Wonders of the world. Babylon was founded at some point prior to the reign of Sargon and seemed to have been a minor city or perhaps a large port town on the Euphrates River.

An artist’s illustration of the Hanging Gardens of Babylon (from deepankoladlatheev.blogspot.com)

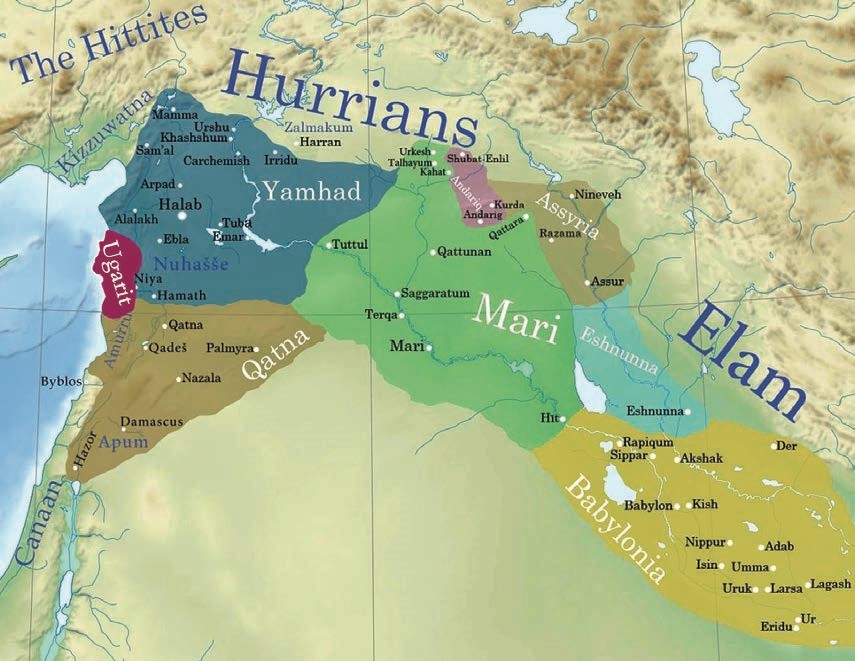

The known history of Babylon begins with its most famous king: Hammurabi (1792 - 1750 B.c.). This obscure prince ascended to the throne upon the abdication of his father and fairly quickly transformed the city into one of the most powerful and influential in all of Mesopotamia. He began his reign by centralising and streamlining his administration, continuing his father’s building programs. He paid careful attention to the needs of the people, improving and maintaining the infrastructures of the cities under his control. He enlarged and heightened the walls of the city, took over great public works, which included opulent temples and canals, and made diplomacy an integral part of the way, he was conducting his affairs. The kingdom of Babylon comprised only the cities of Babylon, Kish, Sippar and Borsippa, when Hammurabi came to the throne, but by 1755 B.c. through a succession of military campaigns, careful alliances made and broken, when necessary, and political manoeuvres he conquered all of the cities and city states of southern Mesopotamia, coalescing them into one kingdom, ruled from Babylon, which at this time was the largest city in the world. Hammurabi also invaded and conquered Elam to the east, and the kingdoms of Mari and Ebla to the north-west. He named his realm Babylonia.

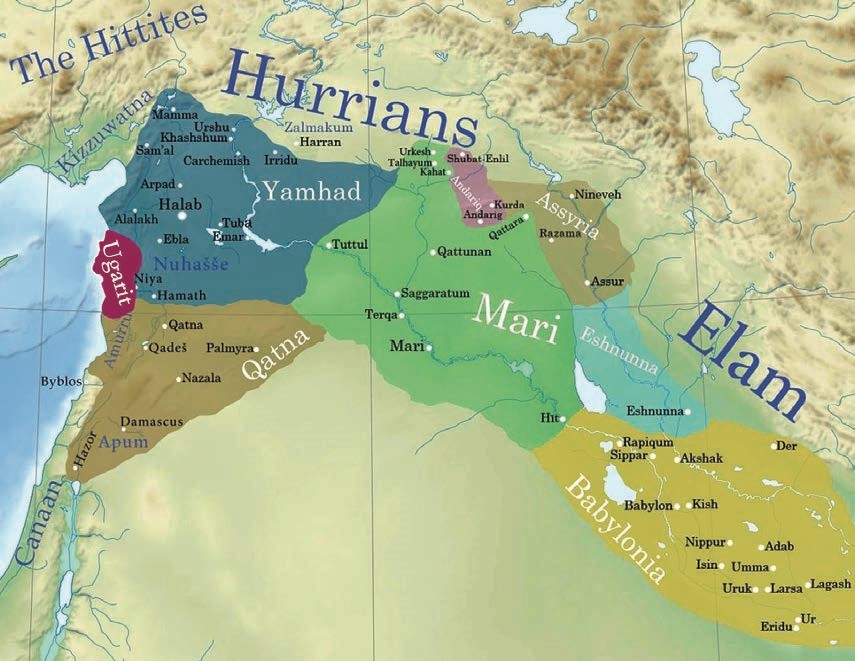

Mesopotamia c. 1764 B.c. by Attar-Aram syria, using a modified map originally made by Sémhur.

He instituted also his famous code of laws, which were inscribed in a column, the stele of the gods. Unlike the earlier Code of Ur-Nammu, the oldest code of laws in the world, which imposed fines or penalties of land, Hammurabi’s code epitomised the principle of retributive justice, in which punishment corresponds directly to the crime, better known as the concept of ‘an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth’. What decided one’s guilt or innocence, however, was the much older method of the ordeal, in which an accused person was sentenced to perform a certain task, usually being thrown into a river to swim a certain distance across, where a success meant innocence, while a failure was proof of guilt.

Hammurabi receiving the Law Codes from Shamash, the Sun god, 2.25 m tall basalt Stele (commons.wikimedia.org by Mbzt )

By 1755 B.c. when he was the undisputed master of Mesopotamia, Hammurabi was old and sick. He died in 1750 B.c. and his son, Samsu-Iluna, was left to hold the kingdom against the invading forces. It was a formidable task, of which he was not capable. The vast realm Hammurabi had built during his lifetime, began to fall apart within a year of his death. None of Hammurabi’s successors could take the kingdom to its former glory and first the Hittites in 1595 B.c. then the Kassites invaded. Babylon eventually became subject to the Assyrians (1365 - 1053 B.c.) to the north, and Elam to the east, with both powers vying for control of the city. The Assyrian king Tukulti Ninurta I took the throne of Babylon in 1235 B.c.

Assyria

A small kingdom called Assyria began a series of successful campaigns and the Assyrian Empire was born. The wealth generated from trade in Cappadocia provided the people of Ashur (also Assur) with the stability and security necessary for the growth and prosperity of the city. The empire began modestly at the city of Ashur located north-east of Babylon. Although the city of Ashur existed since the 3rd millennium B.c. very little is known from that time, because of a dearth of sources. Assyria did belong to the Empire of Akkad at times, as well as to the Third Dynasty of Ur. When Hammurabi ascended to rule, he subjugated the lands of the Assyrians. It is around this same time, that trade between Ashur and Anatolia ended, as Babylon now rose to prominence in the region and took control of trade with Assyria.

After the Babylonian Empire fell apart, Assyria again attempted to assert control over the area surrounding Ashur, but it seems as though the kings of this period were not up to the task. Civil war broke out in the region and stability was not regained until the reign of the Assyrian king Adasi (c. 1726 - 1691 B.c). Adasi was able to secure the region and his successors continued his policies, but they were unable or unwilling to engage in expansion of the kingdom. Later Assyria fell under the control of the Mitanni, a Kingdom that rose from the area of eastern Anatolia and held power in the region of Mesopotamia and after them, the Hittites came to power, until the coming of King Adad Nirari I (c. 1307 - 1275 B.c.) who expanded the Assyrian Empire to the north and south, driving out the Hittites and the Mitanni.

With Mitanni under Assyrian control, Adad Nirari I decided the best way to prevent any future uprising was to remove the former occupants of the land and replace them with Assyrians. Those, that had actively resisted the Assyrians, were killed or sold into slavery, but the general populaces became absorbed into the growing empire and were thought of as Assyrians. Stability was restored and prosperity was ensured. That affluence allowed the king to engage in ambitious projects building city walls, opening canals and restoring temples. He also provided the foundation upon which his successors would build. While the entire Near East fell into a dark age following the so-called Bronze Age Collapse ca. 1200 B.c., Ashur and its empire remained relatively intact.

GREECE

Cyclades Islands

The Greek Bronze Age began around 5.200 years ago, when it was first established a far-ranging trade network. Tin and charcoal were imported to Cyprus, where copper was mined and alloyed with tin to produce bronze. Knowledge of navigation was well developed at this time and reached a peak of skill, that was exceeded only after 1730 with the invention of the chronometer, which enabled the precise determination of longitude.

(oxfordre.com)

In the south-western Aegean there is a group of about thirty islands and numerous islets, the Cyclades. The ancient Greeks called them ‘Kyklades’ imagining them as a circle, kyklos in Greek, around the sacred island of Delos, the site of the holiest sanctuary to god Apollo. Many of these islands were very rich in mineral resources such as iron ores, copper, lead ores, gold, silver, emery, obsidian and marble. The marble of Paros and Naxos is among the finest in the world, while the obsidian of Melos was popular everywhere, as it was considered the steel of its time.

In the 3rd millennium B.c. a distinctive civilisation, commonly called the Cycladic, emerged. At this time metallurgy developed at a fast pace in the Mediterranean. Inhabitants turned to fishing, shipbuilding and exporting of their mineral resources, as trade flourished between the Cyclades, Crete, the mainland of Greece and Minor Asia.

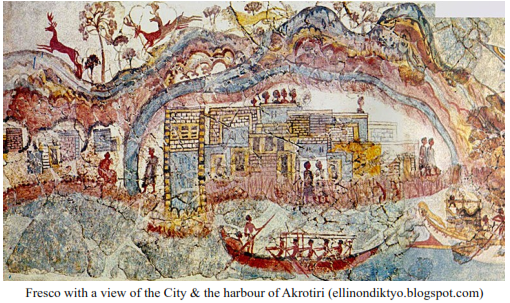

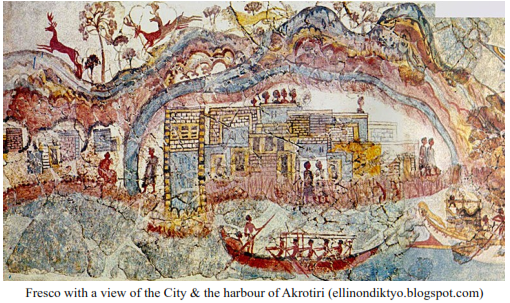

One of the most important settlements of the Aegean was in Akrotiri, on the volcanic island of Thera (Santorini). The first habitation at the site dates from the Late Neolithic times, as early as the 5th millennium B.c., when it was a small fishing and farming village. During the Early Bronze Age a sizeable settlement was founded, which was extended and gradually developed into one of the main urban centres and ports of the Aegean.

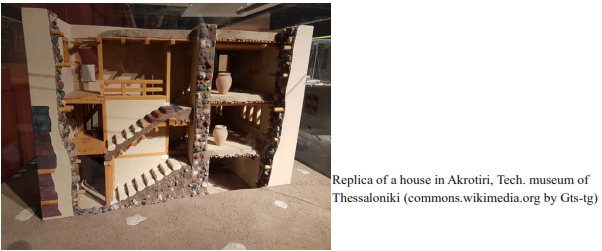

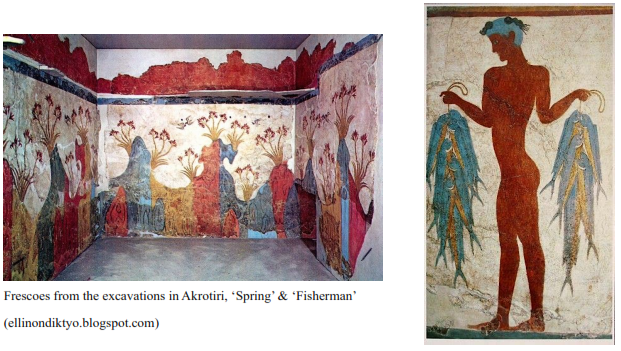

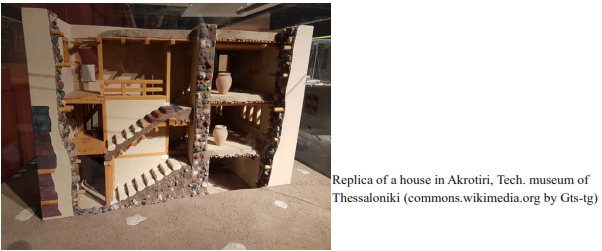

The large extent of the settlement with 30.000 inhabitants, the elaborate drainage system, the paved streets, the sophisticated multi-storey buildings with the magnificent wall-paintings, the earthquake-proof houses, the exquisite pieces of furniture and vessels, the production of high-quality pottery and further craft specialisation, all point to the level of sophistication achieved in Akrotiri.

The various imported objects found in the buildings indicate a wide network of external relations. Thera was too small to be self-sufficient, but its position made it a key trading harbour within the Mediterranean. Its merchants acted as middlemen trading metal, olive oil, wine, pottery and spices with Crete, the Greek Mainland, the Dodecanese, Cyprus, Syria and Egypt. The town’s life came to an abrupt end in the first quarter of the 17th century B.c. when the inhabitants were obliged to abandon it. Akrotiri has been suggested as a possible inspiration for Plato’s story of Atlantis.

2.500 years ago, the Greek Philosopher Plato wrote of an island, he called Atlantis, which was swallowed up by the sea in a single day and night, vanishing without a trace. New research suggests, that Plato’s story was based on true events. Evidence uncovered on Thera have revealed an incredible civilisation advanced beyond its time, destroyed by the greatest disaster of the ancient world. Plato described Atlantis as an island consisting of circular belts of sea and land enclosing one another. Reconstructions of Thera show, how well it fits that description. The island’s unusual landscape has been shaped by the most powerful geological forces. The people were living on a massive volcano.

Around 1620 B.c. the island was hit by a major earthquake measuring more than 7 on the Richter scale, which set in motion an irreversible chain of events. Therans were forced to leave their homes. Their precious possessions were discovered stored beneath solid structures such as wooden doorways and beds. The entrances to their houses were sealed. No human remains were found suggesting, that the islanders moved to temporary camp sites. For over 17.000 years the magma chamber under Thera had been sealed, but the earthquake fractured it allowing the magma to rise releasing sulphur and other poisonous gasses. The pressure from the rising magma blasted out the rock, which was blocking the mouth of the volcano. That was a preeruption. From volcanic deposits we know, that in the early stages of the eruption the island was covered with a light ash enough to contaminate the water supply.

A whole city was covered in ashes and pumice (pictures by saiko3p)

What would make this eruption different from any other before, was the interaction of two kinds of magma triggering a catastrophic chemical reaction, which would thrust an estimated 150 billion tons of magma to the surface. A super-heated column of gas, ash and rock blasted 10 km into the stratosphere forming a mushroom cloud, similar to an atomic bomb. This was the Plinian eruption, the deadliest of all volcanic events. The sound of the eruption was heard as far away as Egypt and within minutes the smog would have been visible from Crete. As the magma cooled down, it fell as pumice, but the ash posed the most immediate threat. It is not like ordinary ash. It contains silicon and once inhaled, it mixes with the moisture in the lunges forming a liquid cement. It makes breathing difficult at first, then impossible. As the crater widened, sea water began to flood in. On contact with the magma the water exploded as steam, triggering the next phase, a new eruption. It is estimated, that the sound pressure would have reached 300 decibels, enough to burst the eardrums of everyone within 15 km radius.

Then lava bombs up to 8 tones would have been hurled everywhere like deadly missiles. As the crater widened more, the pyroclastic flow ensued, a fast-moving current of hot gas and volcanic matter reaching speeds of up to 290 km/h and temperatures of 700 °C. The deadly impact of the eruption extended far beyond the island of Thera. Hour after hour the pyroclastic flow continued pushing volcanic debris into the sea generating huge waves, Tsunami. Travelling at 320 km/h it could have taken only 20 minutes for the first tsunami to reach Crete. By the time the waves hit the coastline, they would have been over 18 metres high. A series of Tsunamis ravaged towns in Crete for hours, if not for days after the eruption, killing more than 30.000 people. As for the people of Thera only very few would have survived.

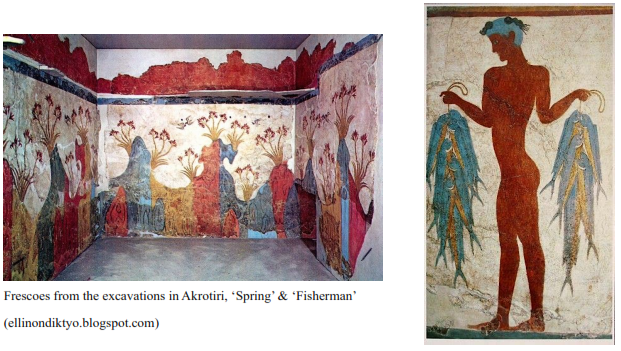

That eruption was 40.000 times most powerful than the Hiroshima bomb. The ash plunged the Mediterranean into weeks of darkness, while global temperatures dropped affecting plant growth as far as Britain. Minoan society was shaken to the core causing deep social unrest. The mixture of volcanic ash and pumice, however, helped preserve the buildings and the remains of fine frescoes, many objects and artworks for more than 3.500 years.

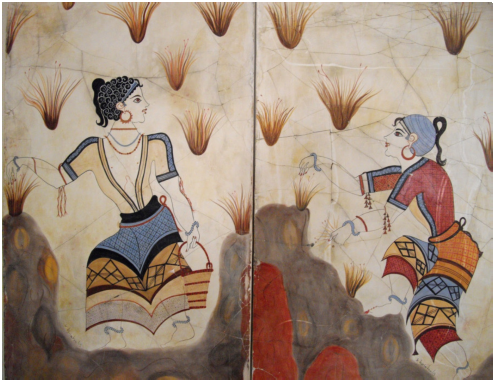

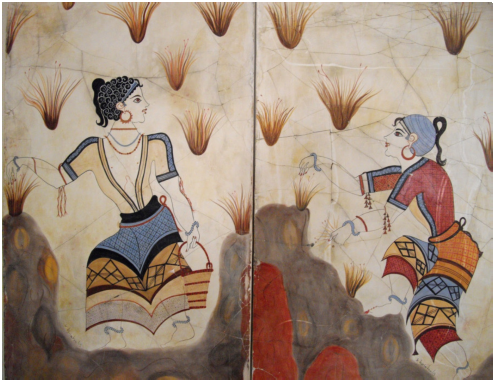

Fresco ‘The saffron gatherers’ c. 1600 B.c. Akrotiri (hellenictheologyandplatonicphilosophy.wordpress.com)

Crete

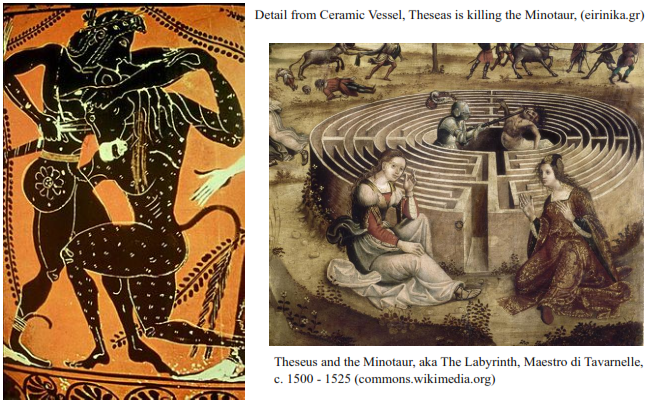

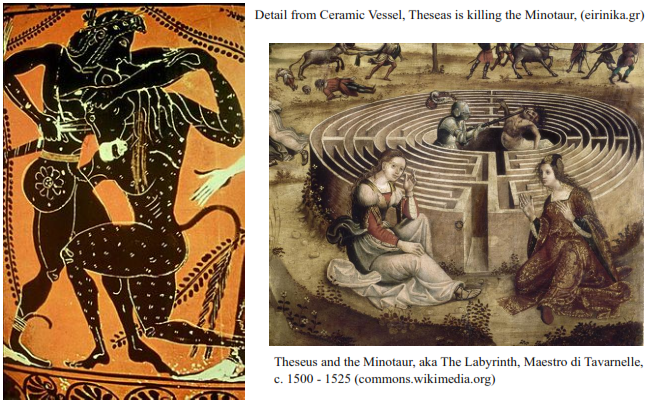

Around 2800 B.c. a new force rose up in the Aegean, the Minoan Crete. The term Minoan refers to the mythic king Minos of Knossos, the most important centre in ancient Crete. The civilisation at Knossos represented a cultural high point in the Mediterranean Sea. According to Greek mythology, it was the capital of King Minos and the home of the labyrinth. They believed, that King Minos had been the first man to establish an empire on sea power, while great technical achievements were associated with the name of his engineer, Daedalus. The Labyrinth, that he was supposed to have built at Knossos, was believed to contain the Minotaur, a fabulous monster half man and half bull, which remained the emblem of the classical Greek Knossos and appeared on its coinage. Some scholars have thought, that the Labyrinth is a confused recollection of the complexity of the palace plan. The Minoan civilisation is considered not only as the first advanced civilisation of the prehistoric Aegean region, but also of the entire Europe.

Crete enjoyed a strategic location. Therefore, the rulers of Crete were able to transform their land into a centre for international maritime trade. They imposed tax on the flow of trade and their seats of power became centres of industrial activity, where goods were manufactured, especially elite items such as bronze weapons, armour and jewellery. Commerce flourished at Knossos, while goldsmiths, sculptors, painters and seal makers were patronised by the royal court to provide high quality products.

The Minoan traders reached far beyond the island of Crete. Their cultural influence extended not only throughout the Cyclades and mainland Greece, where it had a major impact on the emerging Mycenaean civilisation, but in locations such as Egypt, Cyprus, Syria, Canaan, Mesopotamia, Anatolia, Italy, even all the way to Spain. Valuable handicraft items have been found on the Greek mainland, ceramics have been uncovered in Egyptian cities, while the Minoans have imported several items from Egypt, especially papyrus.

The Bronze Age Cretan economy was pre-monetary, thus it did not depend on the use of money. The Minoans implemented a form of centralised economy, in which goods were collected and traded by the palace centres. The goods and produce were sealed and stored in special places, until the time of their transfer to the designated destination. The traded goods were mainly agricultural and dairy produce, while tools and fine pieces of Minoan art also played an important role. Handicrafts made of perishable materials, such as certain fabric and wooden articles, had also a great commercial value. The need for raw materials for the palace artisans was a decisive reason fo