CHAPTER 4

Iron Age

The collapse of the Bronze Age followed the discovery of how to mine ore and make use of iron. The date of the full Iron Age, in which this metal for the most part replaced bronze in implements and weapons, varies depending the region. The transition to the Iron Age was critical because enabled, for the first time in history, true mass-production of metal tools and weapons. Both agriculture and warfare, two prominent examples, were thereby revolutionised. Iron production is known to have taken place in Middle East and south-eastern Europe at least as early as 1200 B.c., with some contemporary archaeological evidence pointing to earlier dates.

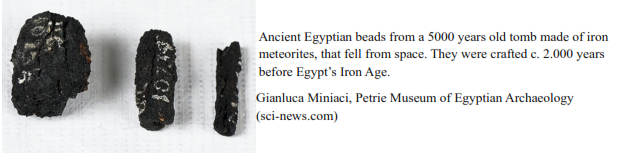

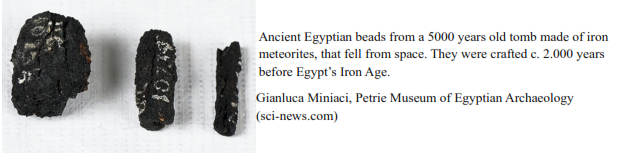

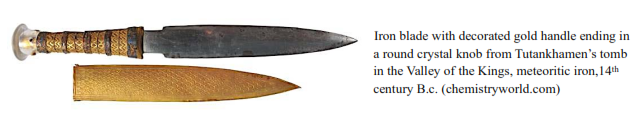

In the Mesopotamian states the initial use of iron reaches far back, to perhaps 3000 B.c. Iron was a scarce and precious metal. The earliest known iron artefacts are nine small beads from burials in Gerzeh, in northern Egypt. They were made from meteoric iron and shaped by careful hammering. Iron’s superior qualities, in contrast to those of bronze, were not fully recognised. It took about 2.000 years, before the iron metallurgy gained its place in the history.

Iron smelting is more difficult than tin and copper smelting. These other metals and their alloys can be cold-worked or melted in simple pottery kilns and cast in moulds. Smelted iron requires hot-working and can be melted only in specially designed furnaces. It is therefore not surprising, that humans only mastered iron smelting after a long time of bronze metallurgy. However, after 1200 B.c. the export of knowledge of iron metallurgy was rapid and widespread. The large-scale production of iron implements had as a consequence new patterns of more permanent settlement. On the other hand, utilisation of iron for weapons put arms in the hands of the masses and set off a series of large-scale movements of peoples, that changed the face of the world.

MESOPOTAMIA

Assyria

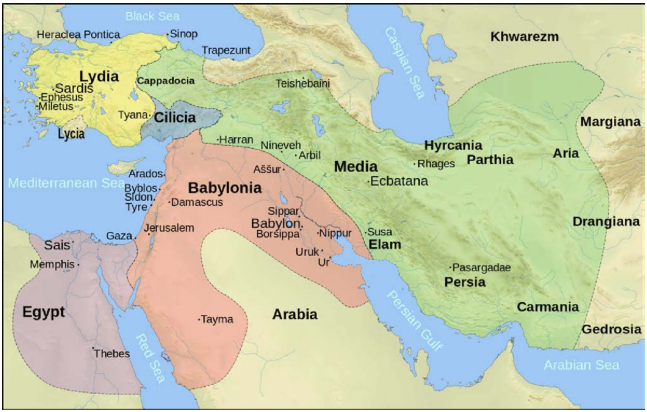

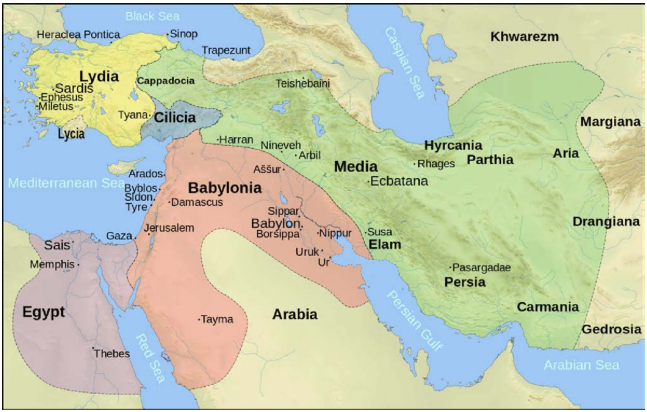

Most Mesopotamian states were either destroyed or weakened following the Bronze Age collapse around 1200 B.c. Unlike other civilisations in the region, which suffered a complete collapse, the Assyrians seem to have come across less challenges. C. 1115 B.c. Tiglath Pileser rose to the throne. He was one of the most important Assyrian kings of this period, mainly because of his wide-ranging military campaigns all the way to the Mediterranean sea, his enthusiasm for building projects like new palace and library, and his interest in collecting cuneiform tablet, which would serve as the model for Ashurbanipal’s famous library at Nineveh. He also issued a legal decree and he was one of the first Assyrian kings to commission parks and gardens arranged with foreign and native trees and plants. The economy was revitalised, and the arts flourished. It is also during his reign, that a significant development occurs, the migrations of the Aramean into Assyria. After his death certain regions, that had been tightly held by Assyria, broke free. For the next century Assyria declined. The empire steadily shrank through repeated attacks from the outside and rebellions from within, entering a period of stasis. It was not until 934 B.c., by which time the Arameans had settled into stable kingdoms in Mesopotamia, that Assyria would reemerge.

Assyria entered into a new phase, the Neo-Assyrian Empire, an era, which most decisively gives the Assyrian Empire the reputation it has for ruthlessness and cruelty. The Assyrian army was the most technologically advanced of its day and it appear to have been amongst the first to use large bodies of cavalry effectively. The Assyrians were the first to make extensive use of iron weaponry, which was not only superior to bronze, but it could be also mass-produced allowing to equip fast very large armies. The iron weapons of their military would prove a decisive advantage in the battles, which would conquer the entire region of the Near East. Reasons for this military aggression have been much debated, with some scholars supporting, that the Assyrians were no more belligerent than their competitors, they just kept better records of their accomplishments. After the political upheaval of the 9th century B.c. the hierarchy reasserted itself. It was essential to harness and organise their resource capacities, to control any threatening groups and to acquire much needed farmland. In their chronicles the Assyrian kings claimed, that the military operations were authorised by the gods, in order their glory to radiate across the empire with every advancement. Therefore, every province under the Assyrian yoke existed to supply all the necessities to satisfy the god’s needs. These states were seemingly independent, however their rulers served as Assyrian vassals, bound by treaties of obedience and subject to annual tribute and taxes. If they failed to fulfil their obligations, they were punished with the utmost severity. The Assyrian kings could destroy cities, enslave entire populations, even exercise mass deportations. A rapid, remorseless retribution in case of rebellion was not just a political tool, but their religious duty. To govern their vast empire the Assyrians developed a network of royal roads and a messenger system long before the Persians. Their economy was based on agriculture and herding, but they also benefited from being situated astride some important trade routes. They were not famous as traders themselves, but rather as tax collectors from merchants passing through.

Ashur-dan II would concentrate on rebuilding Assyria. He built government offices in all provinces, and as an economic boost, he provided ploughs throughout the land, which yielded record grain production. He was followed by four able kings, who used the foundation, which he had laid, to make Assyria the major world power of its time. The kings enjoyed supreme status and without being deified, they embodied godlike attributes to accomplish the will of the gods. They were absolute rulers, whose decisions could not be challenged, and their advisors and ministers were merely servants. The only restriction to their arbitrage was gods’ approval, the power of nobility and the long tradition.

The rise of the king Adad Nirari II (c. 912 - 891 B.c.) brought the kind of revival Assyria needed. He recaptured the lands, which had been lost and secured the borders. He also conquered Babylon but, learning from the mistakes of the past, refused to plunder the city. Instead, he entered into a peace agreement with the king marrying each other’s daughters and assuring mutual loyalty. Their treaty would secure Babylon as a powerful ally for the next 80 years. The following kings continued the same policy of military expansion. Advancements in military technology were not the only contribution of the Assyrians, as they made significant progress also in medicine, building on the foundation of the Sumerians. King Ashurnasirpal II made the first systematic lists of plants and animals in the empire and brought scribes with him on campaigns to record new species. Schools were established throughout the empire, but they were only for the sons of the nobility.

Women were not allowed to attend school or hold positions of authority.

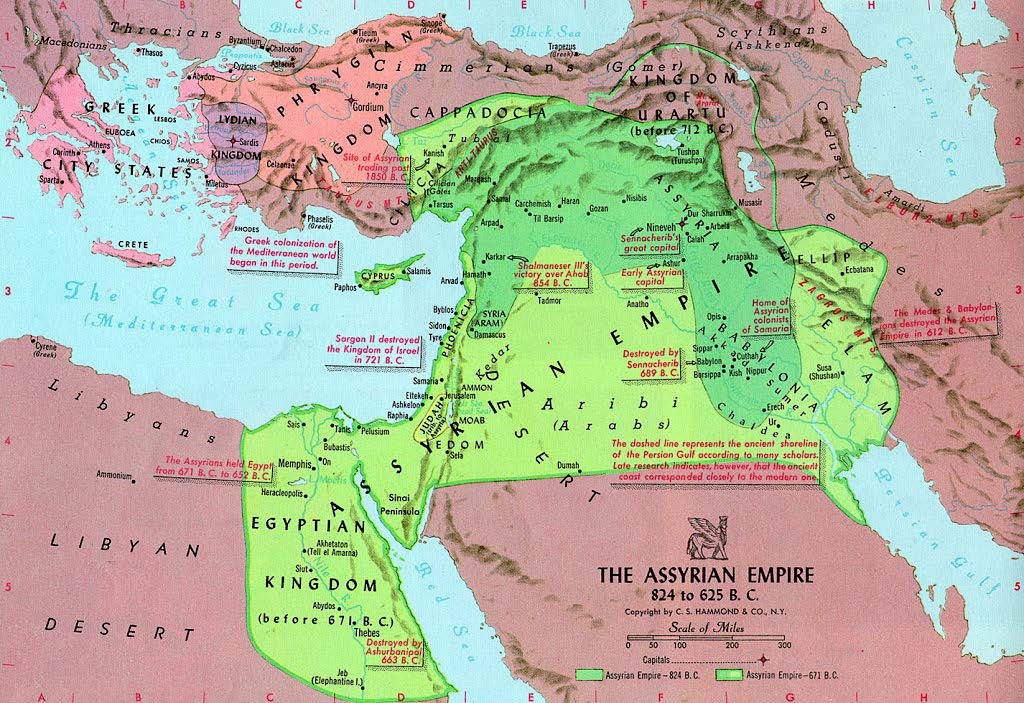

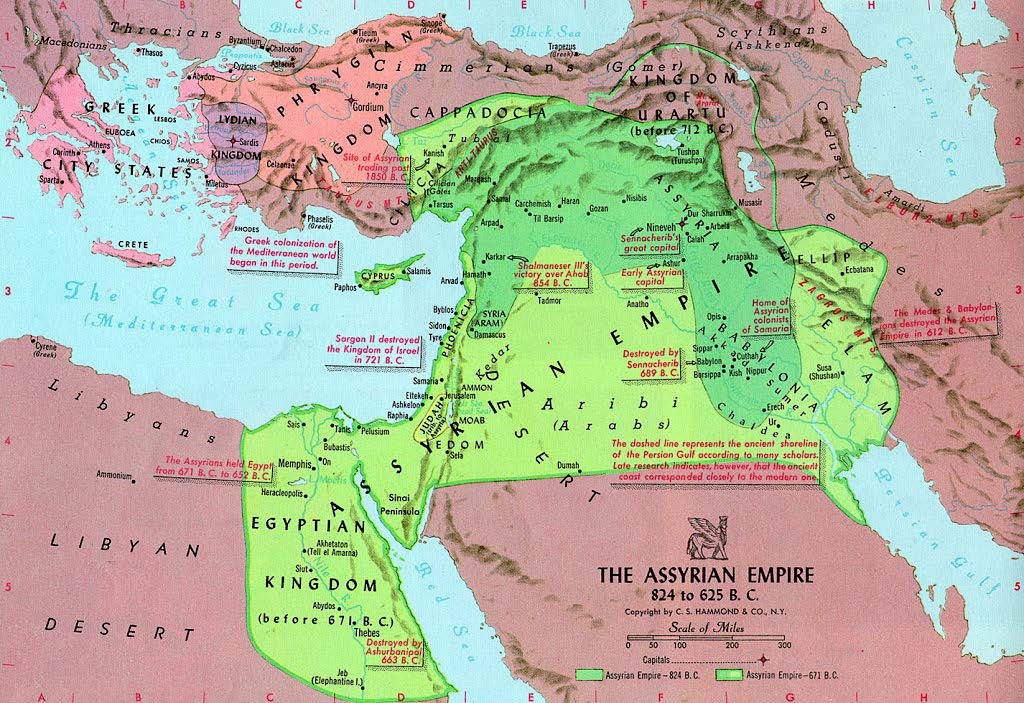

Map of Assyrian Empire (assyrierutangranser.se)

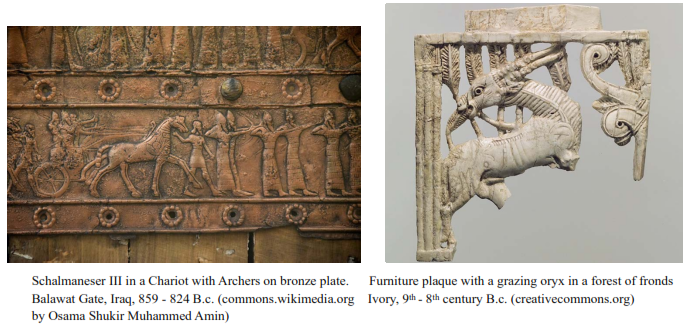

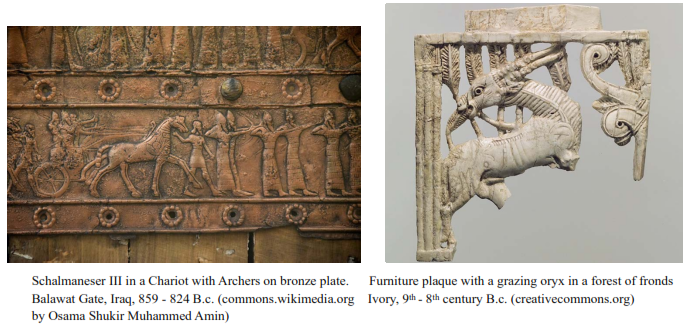

Shalmaneser III (859 - 824 B.c.) expanded the empire up through the coast of the Mediterranean and received tribute from the wealthy Phoenician cities of Tyre and Sidon. The regent Shammuramat, also known as Semiramis, held the throne for her young son Adad Nirari III from c. 811 - 806 B.c. and secured the borders of the empire organising successful campaigns to put down the Medes, who lived in the north-western part of present - day Iran, and others. Her son expanded the empire even further. His successors however preferred to rest on the accomplishments of the predecessors and the empire entered another period of stagnation.

The empire was revitalised by Tiglath Pileser III (745 - 727 B.c.), who reorganised the military and restructured the bureaucracy of the government. Following Tiglath Pileser III’s lead, Sargon II (722 - 705 B.c.) was able to bring the empire to its greatest height. He was followed by Sennacherib (705 - 681 B.c.), who campaigned widely and ruthlessly, conquering Israel, Judah and the Greek provinces in Anatolia. His military victories increased the wealth of the empire. He moved the capital to Nineveh and built, what was known as ‘the Palace without a Rival’. He restored and even improved the city’s original structure, planting orchards and gardens.

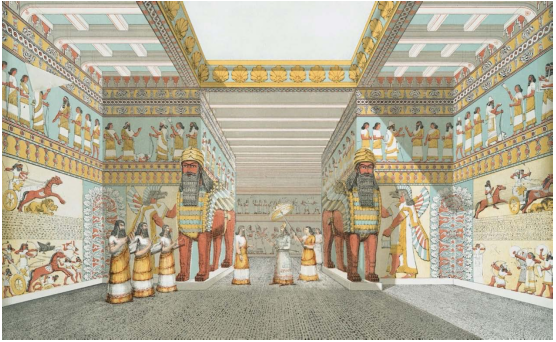

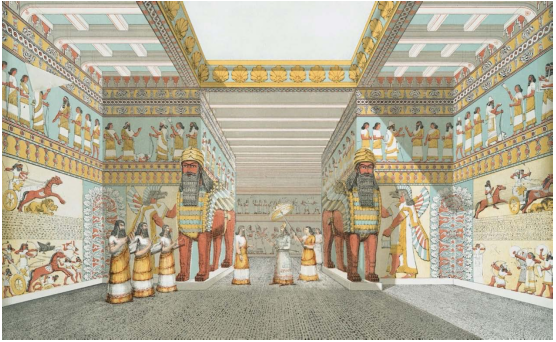

Layard’s representation of Sennacherib’s Palace, 210m x 200m with at least 80 rooms (learningsites.com)

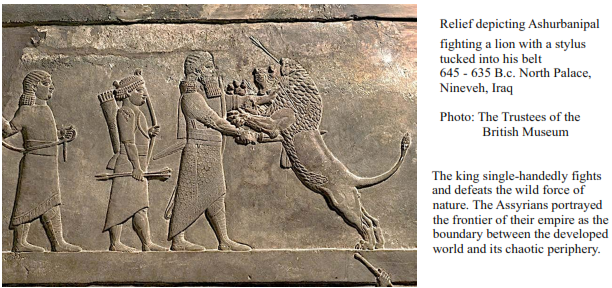

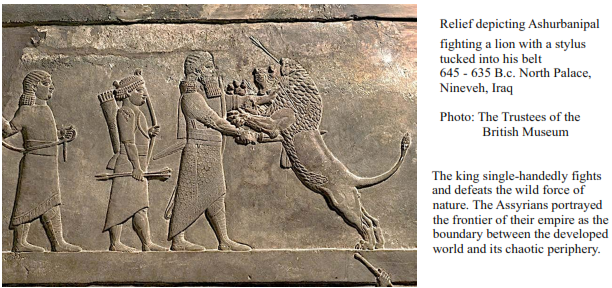

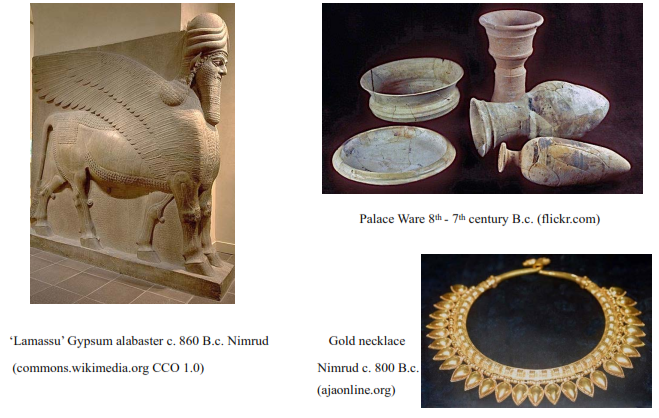

The key Assyrian sites, Ashur, Nimrud, Nineveh etc. were all located in a triangle close to the river Tigris. They were large urban centres, densely inhabited, following a very distinctive town planning with inner and outer cities, excessive fortifications and impressive gateways to the royal courts. At the centre of the city was the vast royal palace. The kings constructed a series of magnificent palaces, where the walls of the courtyards and the throne rooms were decorated with massive, elaborately carved stone reliefs with themes of the king’s traditional roles as monarch, high priest, warrior and hunter. The scenes on the reliefs actively promoted the power and the invincibility of the king and his army and were generally made for propaganda purposes.

Sennacherib ignoring the lessons of the past drove his army against Babylon, sacked it and looted the temples. The looting and destruction of the temples of Babylon was seen as the height of sacrilege by the people of the region and also by Sennacherib’s sons, who assassinated him in his palace, after he had chosen his youngest son, Esarhaddon, as heir in 683 B.c. The destruction of Babylon served as the excuse, they needed to act against the king and his will.

His son Esarhaddon (681 - 669 B.c.) took the throne and one of his first projects was to rebuild Babylon. The empire flourished under his reign. He successfully conquered Egypt and established the empire’s borders as far north as the Zagros Mountains (modern day Iran) and as far south as Nubia (modern Sudan). His successful campaigns and careful maintenance of the government provided the stability for some advances in medicine, mathematics, astronomy, architecture and the arts. Durant writes: “In the field of art, Assyria equalled her preceptor Babylonia and in bas-relief surpassed her. Stimulated by the influx of wealth into Ashur, Kalakh and Nineveh, artists and artisans began to produce for nobles and their ladies, for kings and palaces, for priests and temples jewels of every description, cast metal as skilfully designed and finely wrought as on the great gates at Balawat and luxurious furniture of richly carved and costly woods strengthened with metal and inlaid with gold, silver, bronze, or precious stones.”

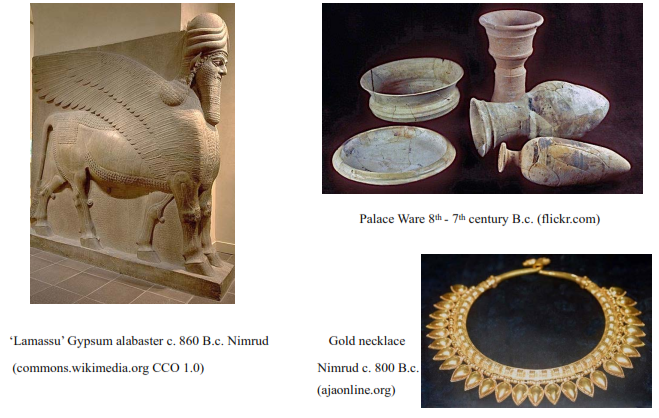

The numerous wars enriched the Assyrian Empire enormously. The confiscated items were amassed in great quantities and kept in the capitals. Furniture was particularly prised by the Assyrian court, however wooden chairs, tables and footrests of the palaces have all perished. What remains are the ivory inlays, that decorated them. Sculpture also reached a high level during this period. One prominent example is the human-headed, winged bull called ‘Lamassu’, which guarded the entrances to the king’s court with the intention to prevent evil. One of the most abundant commodities in Assyria was pottery. The finest one is the ‘Palace Wares’ consisting of eggshell thin-walled bowls and beakers. Below the palaces there were vaulted tombs and family crypts. All the kings were buried at Assur, the traditional capital, while the royal women at Nimrud, Nineveh and Khorsabad. These tombs contained grave goods, including gold jewellery and vessels of outstanding quality and artistry.

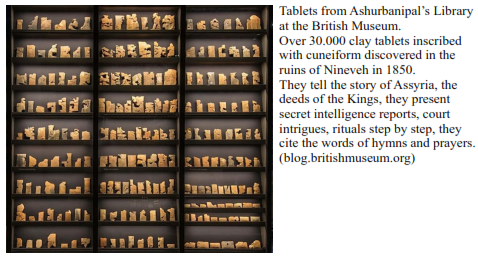

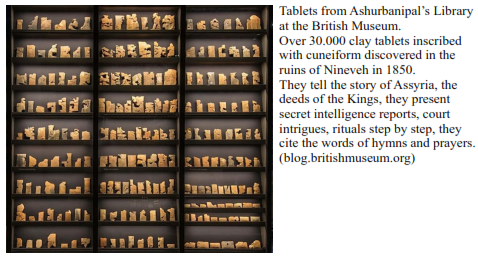

In order to secure the peace, Esarhaddon’s mother, Zakutu, entered into vassal treaties with the Persians and the Medes requiring them to submit in advance to his successor. When he died, rule passed to the last great king, Ashurbanipal (668 - 627 B.c.) He was the most literate of the rulers and he is probably best known in the modern day for the vast library he founded at his palace at Nineveh. Though a great patron of the arts and culture, he could be just as ruthless as his predecessors in securing the empire and intimidating his enemies. The empire had grown too large, however, and the regions were overtaxed. Further, the vastness of the Assyrian domain made it difficult to defend the borders. As great in number as the army remained, there were not enough men to keep garrisoned at every significant fort or outpost.

Ashurbanipal’s Palace on the banks of Tigris river in Nimrud. Photo by Heritage Images (nationalgeographic.org)

When Ashurbanipal died in 627 B.c., the empire began to fall apart. In 612 B.c. Nineveh was sacked and burned by a coalition of Babylonians, Persians, Medes and many others. The destruction of the great Assyrian cities was so complete that, within two generations of the empire’s fall, no one knew, where the cities had been. The ruins of Nineveh were covered by the sands and lay buried for the next 2.000 years.

Thanks to the Greek historian Herodotus, who considered the entire Mesopotamia ‘Assyria’, scholars have long known the culture existed, as compared to the Sumerians, who were unknown to scholarship until the 19th century. Amongst the greatest of their achievements, however, was the Aramaic alphabet, which was imported into the Assyrian government by Tiglath Pileser III from the conquered region of Syria. Aramaean was easier to write than Akkadian, so older documents collected by kings such as Ashurbanipal, were translated from Akkadian into Aramaic. As a result, thousands of years of history and culture were preserved for future generations.

Babylonia

In the 12th century B.c. Babylon remained weak and subject to Assyria. Its ineffectual native kings were unable to prevent new waves of foreign west Semitic settlers from the deserts of the Levant, including the Aramaeans in the 11th century B.c. and the Chaldeans in the 9th century B.c. During the rule of the Neo Assyrian Empire (911 - 609 B.c.) Babylonia was under constant Assyrian domination or direct control. After the death of Ashurbanipal and the destabilisation of the Assyrian empire, Babylon, like many other parts of the near east, took advantage of the anarchy, that prevailed, to set itself free. Following the decline and rupture of the Assyrian empire, Babylon assumed supremacy in the region, which resulted in the rise of the Neo-Babylonian Empire. Even though Aramaic became the everyday tongue, Akkadian was retained as the language of administration and culture.

Neo-Babylonian Empire in the 6th century B.c. (commons.wikimedia.org)

With the recovery of Babylonian independence, a new era of architectural activity ensued, particularly during the reign of Nebuchadnezzar II (604 - 561 B.c). In 605 B.c. his father defeated the Egyptian and the Assyrian army and brought the region of Syria and Phoenicia under the control of Babylon. Nebuchadnezzar engaged in several military campaigns designed to increase Babylonian influence in Aramaea and Judah. Numerous rebellions took place amongst the Phoenician and the Canaanite states, and he soon retaliated by capturing and destroying Jerusalem (587 B.c.) deporting many of the prominent citizens. After that he initiated a thirteen-year siege of Tyre, which ended in a compromise with the Tyrians accepting Babylonian authority. Then he turned against Egypt. He controlled all the trade routes across Mesopotamia from the Persian Gulf to the Mediterranean Sea. By 572 B.c. Nebuchadnezzar was in full control of Babylonia, Assyria, Phoenicia, Israel, Philistine, northern Arabia and parts of Minor Asia. He fought the Pharaohs throughout his reign and in 568 B.c., during the reign of Pharaoh Amasis, he invaded Egypt itself.

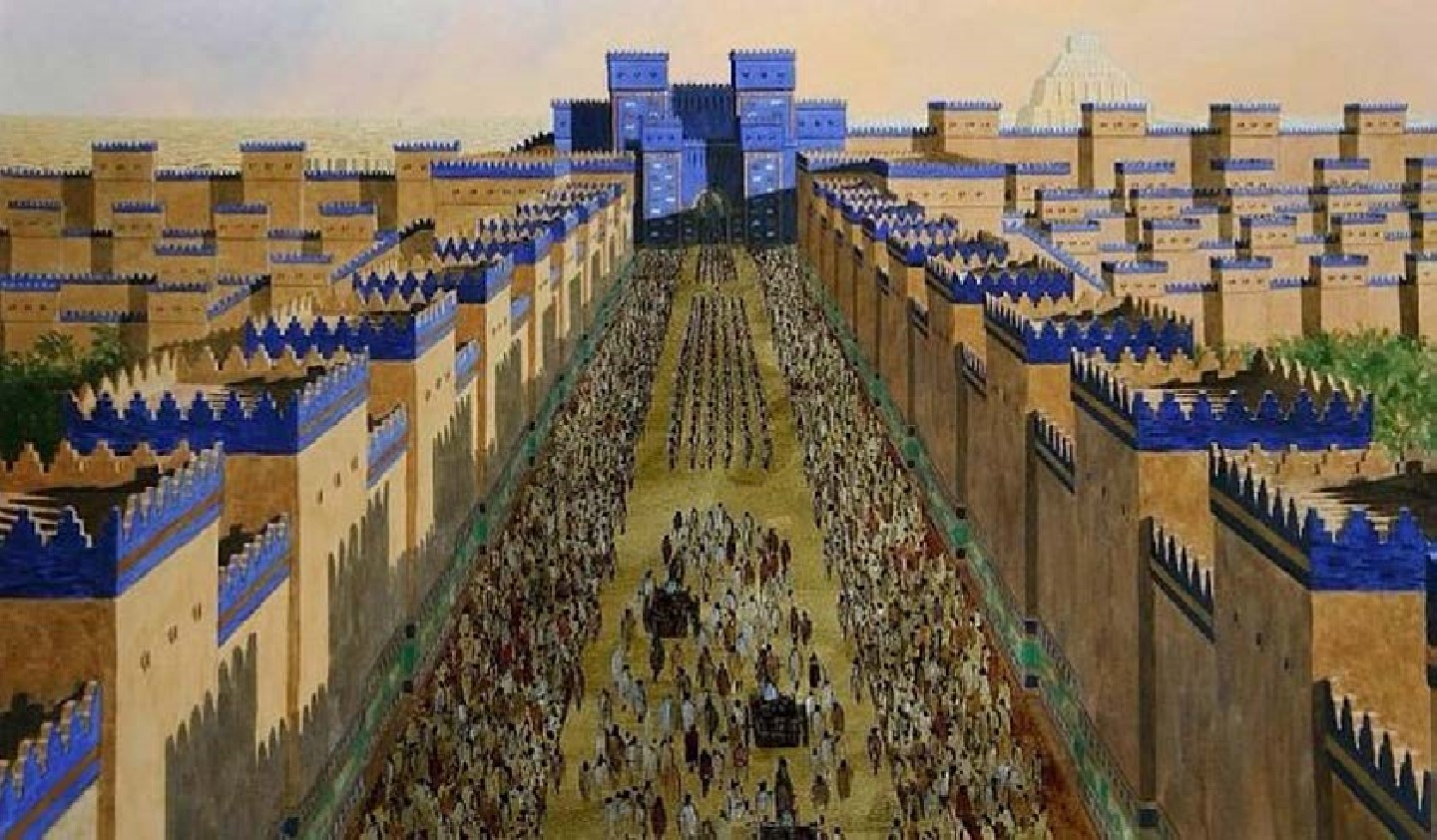

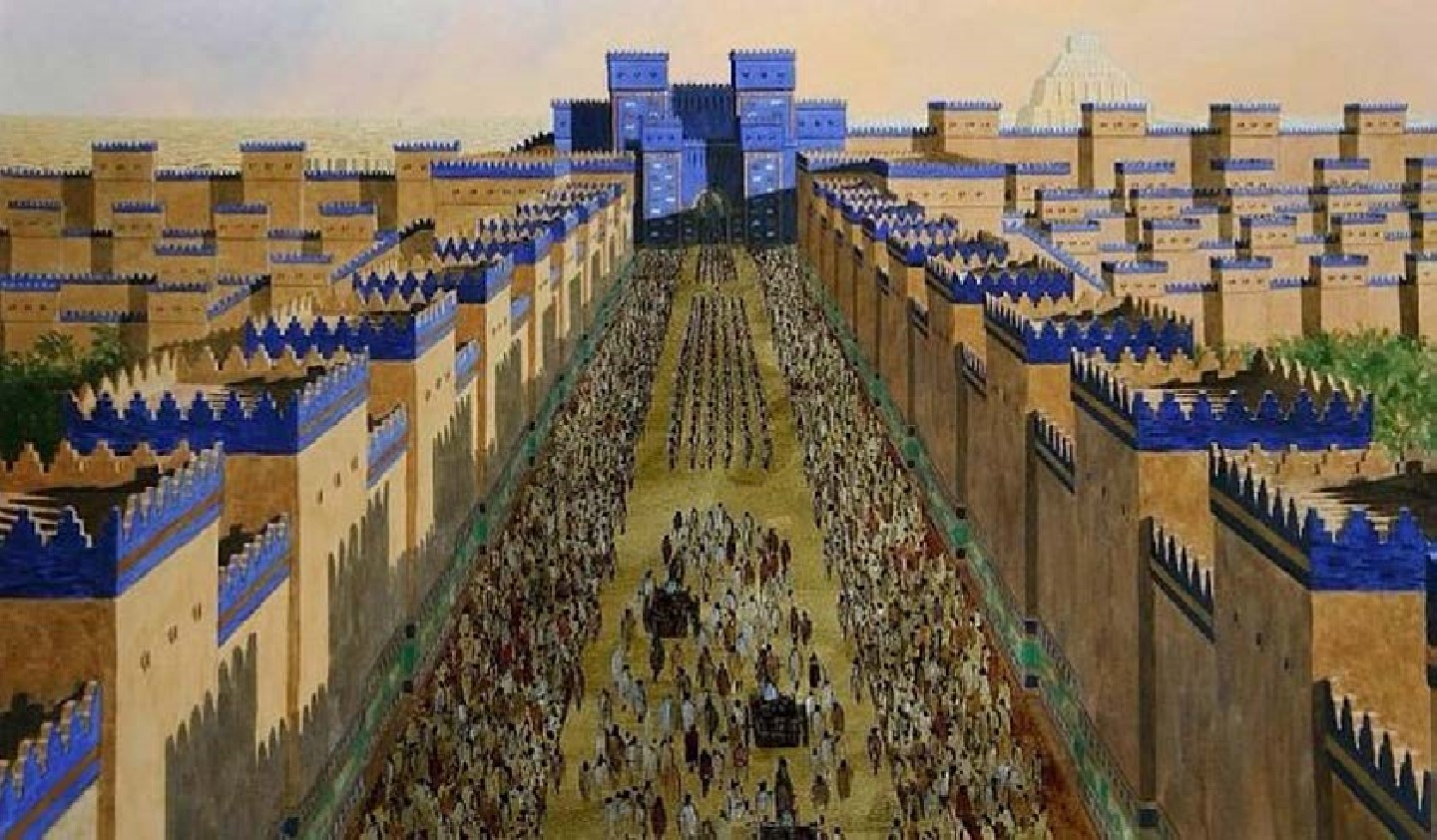

Nebuchadnezzar rebuilt all the major cities on a lavish scale and decided to adorn Babylon with luxurious splendour for all mankind to behold in awe. So, he constructed canals, aqueducts, temples, reservoirs, and an underground passage along with a stone bridge connecting the two parts of the city separated by the Euphrates river. He ordered the complete reconstruction of the imperial grounds, including the Etemenanki Ziggurat ‘House of the Frontier Between Heaven and Earth’, which lay next to the temple of Marduk and the construction of the Ishtar Gate, the most prominent of eight gates around Babylon. The entire gate was covered in gold and lapis lazuli glazed bricks, which would have rendered the façade with a jewel-like shine, while alternating rows of lion and cattle were marching in a relief procession across its gleaming blue surface. The gate served as a symbol for the citizens of Babylon and the visitors as well, that this is a city of incredible wealth and strength.

‘Ishtar Gate’ reconstructed with materials from the original build-site (commons.wikimedia.org By Radomir Vrbovsky)

Furthermore, the great temples and monuments were accented and they were easy accessible by new roads. Special attention was dedicated to the construction of the Processional Way for the festival of Marduk, during which the god’s statue was paraded through the city and outside beyond the gates. This road was 21m wide and almost 1km long, paved with limestone, while the walls rose 15m high on every side. These impressive walls were adorned with more than 120 colourful, glazed-brick reliefs depicting lions, dragons, bulls and flowers in gold. For Babylon nothing was spared, neither cedar-wood, nor bronze, gold, silver, rare and precious stones. The city itself was rendered impregnable by the construction of a triple line of walls so thick, that chariot races were conducted around the tops, which stretched ninety miles in length encircling an area of 500 km2. The bricks of the walls were faced with a bright blue and bore the inscription, ‘I am Nebuchadnezzar, King of Babylon’.

He is also credited with the restoration of the Lake of Sippar, the opening of a port on the Persian Gulf and the construction of the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, which is said to have been built for his homesick wife Amyitis, to remind her of her homeland. She was the daughter of the king of the powerful Median Empire, which laid on the north. This was a political marriage to ensure peace between the two empires. These undertakings required a considerable number of labourers. An inscription at the great temple of Marduk suggests, that the labouring force used for his public works was most likely made up of captives brought from various parts of western Asia.

Reconstruction of the city of Babylon- Procession Way leading to Ishtar Gate and a Ziggurat in the distance

(chenarch.com)

Urban life flourished during this period. The cities were autonomous and enjoyed special privileges from the kings. They had their own law courts and the social structure was dominated by the temples. Free labourers like craftsmen maintained high status, while the countryside was dominated by large estates, which were granted to government officials as a form of payment. The estates were usually managed by local entrepreneurs, who acquired part of the profits. Rural folk were bound to these estates providing both labour and rents to their landowners.

In 539 B.c. the Neo-Babylonian Empire fell to king of Persia, Cyrus, who founded the Achaemenid Empire. Under Cyrus and the subsequent king Darius, Babylon became the capital city of the 9th Satrapy, as well as a centre of learning and scientific advancement. The ancient arts of astronomy and mathematics were revitalised and the scholars completed maps of constellations. The city became the administrative capital of the Persian Empire and remained prominent for over two centuries.

‘Lion of Babylon’, black basalt, 2m long & 7 tons, at the time of Nebuchadnezzar II 6th century B.c

(commons.wikimedia.org by David Stanley)

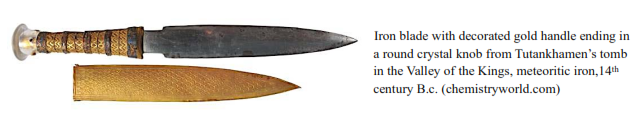

EGYPT

Iron metal is singularly scarce in collections of Egyptian antiquities. Bronze remained the primary material until the conquest by Assyria. Indeed, the supremacy of iron weapons over the copper-alloy has been seen as one of the major factors in the demise of Egypt. Although the first evidence for iron smelting appears in the archaeological record only in the 6th century B.c., the Egyptians were crafting beads and trinkets from it for thousands of years harvesting the metal from fallen meteorites. The rarity of the metal gave it a special place in their society. To the ancient Egyptians, iron was known as the ‘metal of heaven’, because something, that fell from the sky, was regarded as a gift from the gods. Therefore, it was strongly associated with royalty and power. Only a handful of iron artefacts have been discovered in the region from before the 6th century B.c. All come from high-status graves, such as that of the pharaoh Tutankhamen. Objects made of such divine material were believed to guarantee priority passage into the afterlife.

Egypt’s great wealth had attracted the attention of the Sea People, of mysterious origins, who began to make regular incursions along the coast. Between 1276 - 1178 B.c. the Sea Peoples were a threat to Egyptian security. Ramses III fought them off defeating them at the Battle of Xois in 1178 B.c. The kings, who followed, were not very efficient. They attempted to maintain his policies, but they were addressed with resistance from the people of Egypt, those in the conquered territories, and, especially, the priestly class. The priests of Amun had acquired large tracts of land and accumulated great wealth, which now threatened the central government and disrupted the unity of Egypt. Centralised government under the 21st dynasty pharaohs gave way to the resurgence of local officials, who were virtually autonomous. Egypt lost its provinces in Palestine and Syria for good and suffered from external invaders, while its wealth was being steadily and inevitably exhausted.

At the same time foreigners from Libya and Nubia grabbed power for themselves like King Sheshonq, a descendant of Libyans, who had invaded Egypt and settled there.

In the 8th century B.c. Egypt clashed with the growing Assyrian empire. In 671 B.c. the Assyrian ruler Esarhaddon drove the king Taharka out of Memphis and destroyed the city. Then he appointed his own rulers out of local governors and officials loyal to the Assyrians. Having made no long-term plans for control of the country, he left it in ruins in the hands of the local rulers and abandoned Egypt to its fate.

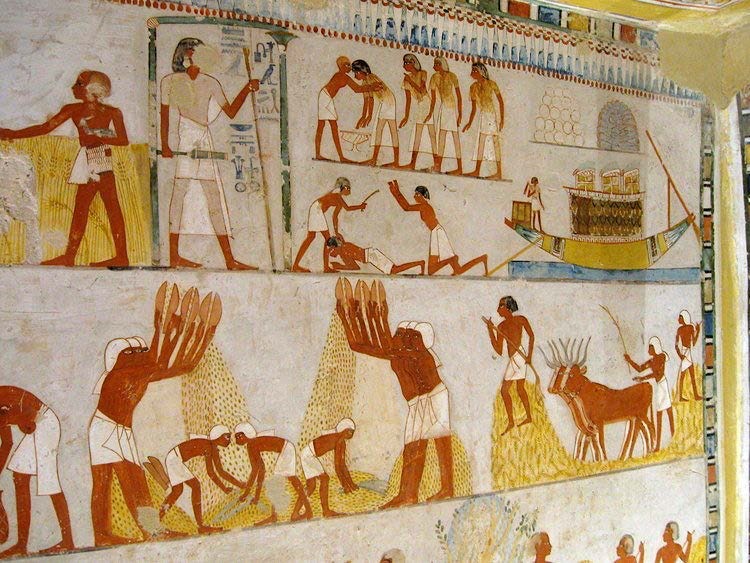

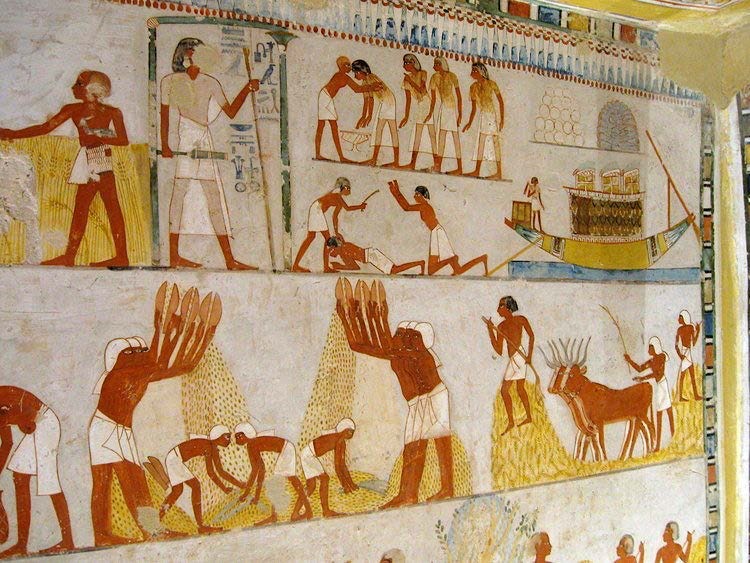

Workers depicted in a mural at the tomb of Menna at Thebes, 18th Dynasty

Photo by Horus3, Flickr, Creative Commons

Egypt operated on a barter system up until the Persian invasion and the economy was based on agriculture. The people worked the land, while the government collected the bounty and then distributed it to the people according to their needs. Farmers were the backbone of the economy and sustained everyone else. They usually did not own the land, so they were given food, implements and living quarters in return for their labour. They rose before sunrise, worked the fields all day and returned home towards sunset. Their wives would often maintain small gardens to supplement the meals for the family or to trade for other necessities.

In 525 B.c., Cambyses II, king of Persia, defeated Psammetichus III and Egypt became part of the Persian Empire. Knowing the reverence Egyptians held for cats, who were thought to be living representations of the goddess Bastet, Cambyses II ordered his men to paint cats on their shields and to place cats and other animals sacred to the Egyptians, in front of the army. The Egyptian forces surrendered and the country fell to the Persians. Persian rulers such as Darius (522 - 485 B.c.) ruled the country largely under the same terms as native Egyptian kings: Darius supported Egypt’s religious cults and undertook the building and restoration of its temples. It would remain under Persian occupation until the coming of Alexander the Great in 332 - 331 Bc., who was welcomed as a liberator and conquered Egypt without a fight.

PHOENICIA

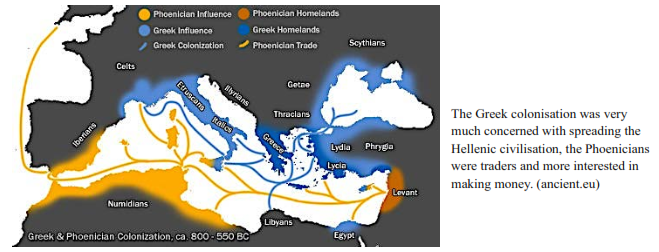

Phoenicia was an ancient thalassocratic civilisation situated on the western, coastal part of the Fertile Crescent right on the coastline of what is today Lebanon, Palestine, Israel and Syria. The origins of the Phoenicians are still unclear. Where they came from, when they arrived and under what circumstances, are all still debatable. They spread across the Mediterranean from 1500 B.c. to 300 B.c. The high point of Phoenician culture is usually placed c. 1200 - 800 B.c. As it is already mentioned, with the collapse of the Bronze Age around 1200 B.c. a series of events weakened and destroyed the adjacent Egyptian and Hittite empires. In the resulting power vacuum, a number of Phoenician cities rose as significant maritime powers.

The most important Phoenician settlements were Byblos, Tyre, Sidon, Simyra and Berytus. Carthage was founded in 814 B.c. directly across Sicily, with the purpose to monopolise the Mediterranean trade beyond that point and to keep their rivals from passing through.

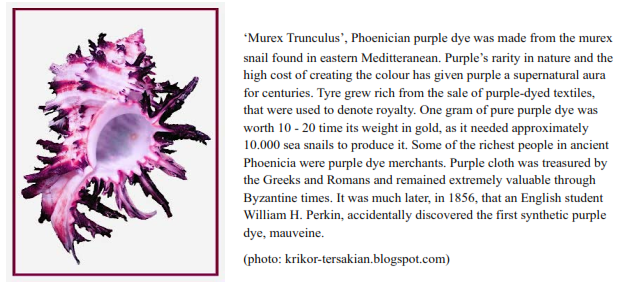

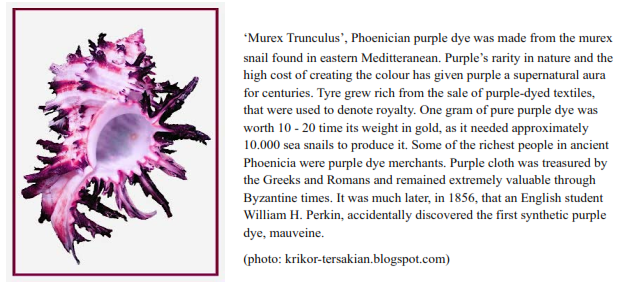

Phoenicia is a Greek term, a reference to the valuable murex-shell purple dye they exported and derives from the Greek word ‘phoínios’ meaning deep red - purple. It was used by the Greek elite and the Mesopotamian royalty to colour garments.

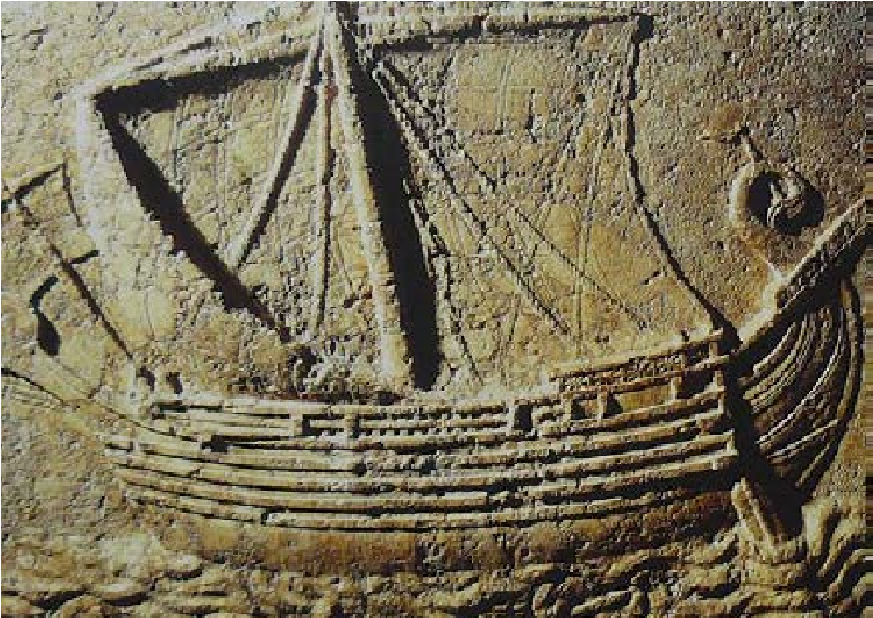

The Phoenicians were great sailors. They managed to sail as far west as present-day Morocco and Spain carrying huge cargoes of goods for trade, to which they owed much of their prosperity. A Carthaginian expedition explored and colonised the Atlantic coast of Africa all the way to the Gulf of Guinea and according to Herodotus another expedition sent down the Red Sea by pharaoh Necho II of Egypt (c. 600 B.c.) and circumnavigating Africa returned through the Pillars of Hercules, on the strait of Gibraltar, after three years.

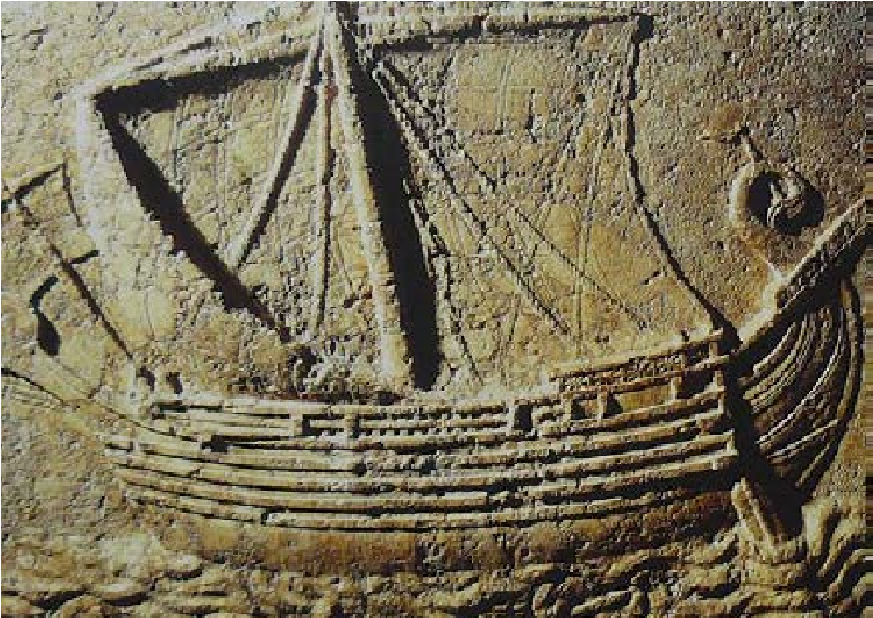

Phoenician Ship carved on the face of a sarcophagus, 2nd century (commons.wikimedia.org)

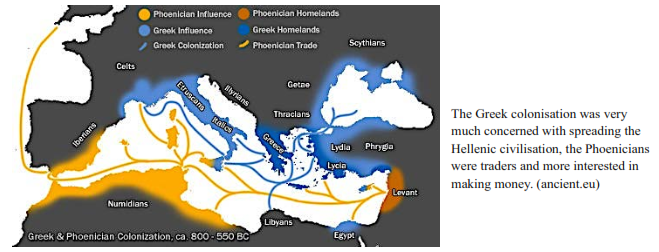

The Phoenicians were not an agricultural people, because most of the land was not arable. Therefore, they focused on commerce and trading instead. At first, they traded mainly with the Greeks, selling wood, slaves, glass and the purple dye. As trading and colonising spread over the Mediterranean, Phoenicians and Greeks seemed to have split that sea in two: the Phoenicians dominated the southern shore, while the Greeks were active along the northern shores. The two cultures rarely clashed, except at the island of Sicily, which eventually was divided into two spheres of influence. To Egypt, where grapevines would not grow, they sold wine. Pottery kilns at Tyre produced the big terracotta jars used for transporting wine and from Egypt they bought gold. From elsewhere they obtained other materials, perhaps the most important being silver from Sardinia and the Iberian Peninsula.

Regarding their prosperity Greek philosopher Plato contends, that the love of money is a tendency of the soul found amongst Phoenicians and Egyptians, which distinguishes them from the Greeks, who tend towards the love of knowledge. In his book ‘Laws’ he asserts, that this love of money has led the Phoenicians and the Egyptians to develop skills in cunning and trickery rather than wisdom.

The Phoenicians are credited by many scholars with spreading their alphabet throughout the Mediterranean world and there is an allegation, that the Greeks adopted the majority of these letters, but changed some of them to vowels, which were significant in their language, giving rise to the first true alphabet. That theory is disputed by many scholars, who actually claim the exact opposite. If the Phoenicians had actually invented such an ingenious, startling tool, why didn’t they use it? What did they produce with it? History, science, literature? Did they write poetry or tragedy or comedy? So, these claims seem rather dubious.

Furthermore, the Phoenicians were notorious in antiquity for their intensity of their beliefs, especially the Carthaginians. They were also known for their superstition. They imagined th