CHAPTER 1

Athenian Democracy

The archaic period is considered to be one of the most fruitful periods of Greek chronicles, that saw advancements in political theory, in culture and art, which led ultimately to the one and only wonder ever witnessed in the human history.

Mycenaean Greece of the Bronze Age had been divided into kingdoms, each containing a territory and a population distributed into both small towns and large estates owned by the nobility. The kingdom was ruled by a king claiming authority under divine right and physically established at a palace situated within a citadel. During the collapse of the Bronze Age the palaces, kings and estates vanished, population declined, towns were abandoned or became villages situated in ruins and government devolved on minor officials and tribal structure.

The power of the king was reduced as aristocratic gatherings, such as the council of elders, increased in power. The sharing of power among powerful families occurred in many ‘poleis’ cities, which saw oligarchies established. These aristocratic families were constantly competing against one another to gain territory, money, or status. They lived in a closed community of festivals, lavish meals and athletic games, that had nothing to do with the common people and farmers of Greece.

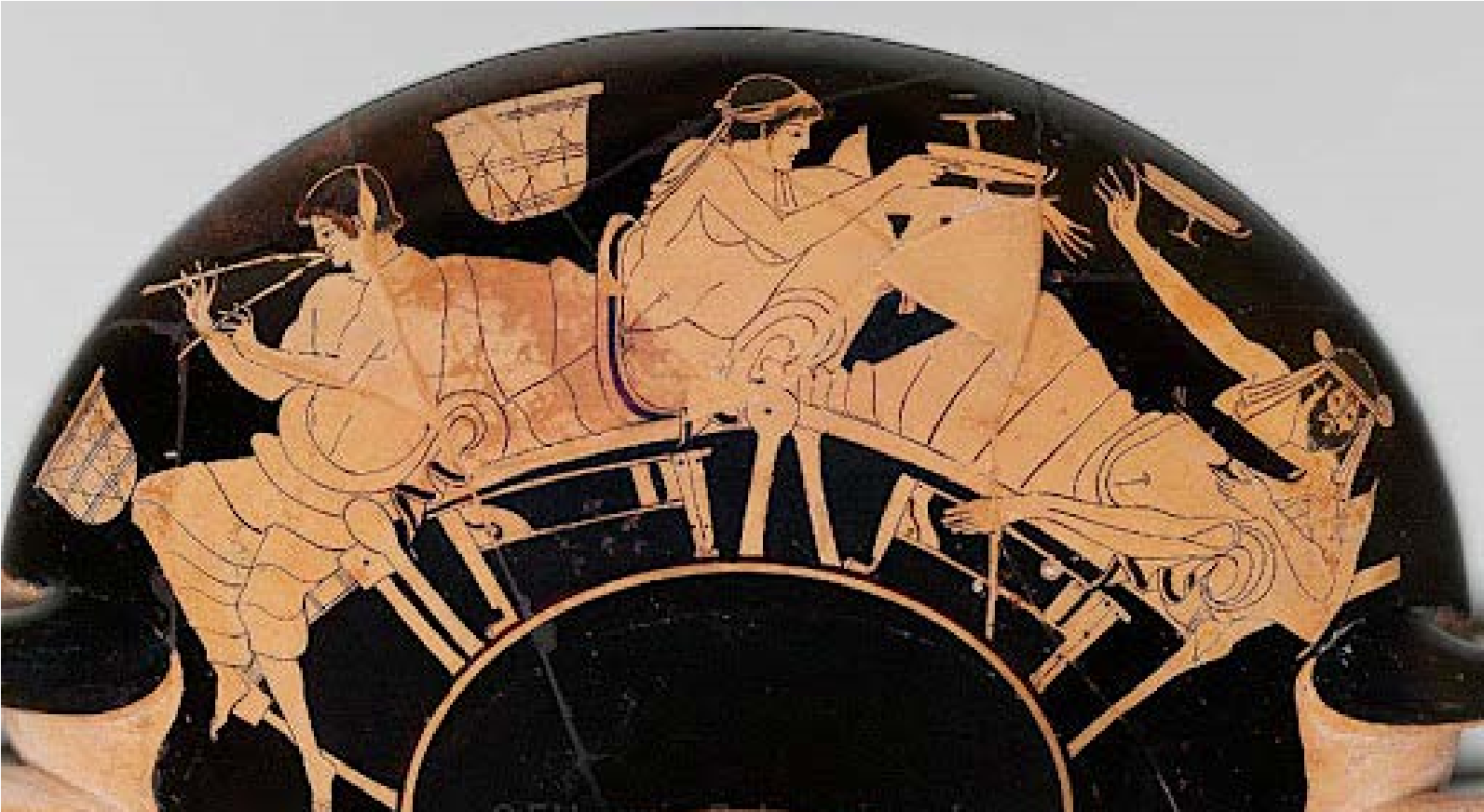

Archaic Vase Painting, scene of an aristocratic festivity, (users.sch.gr)

The farmers of Greece lived under a subsistence lifestyle and were frequently victims of crop failures. The poet Hesiod writes of many different circumstances, that could befall an archaic Greek farmer, all of which would force him to borrow goods from his neighbours. Failure to pay back these goods could lead to debt, loss of the farm, or even enslavement. Due to the sharp increase in population, arable farmland, which had always been scarce, now became insufficient to support all the people. In 750 -600 B.c. Greece was marked by widespread famines. By 600 B.c. almost all of the farmers in Athens had been dispossessed of their property and worked as slaves on the same land. Furthermore, a majority of the most important and powerful city-states were ruled by tyrants, a Greek word meaning illegitimate ruler, who seized power from the aristocracy tended to set up a dictatorship within the polis.

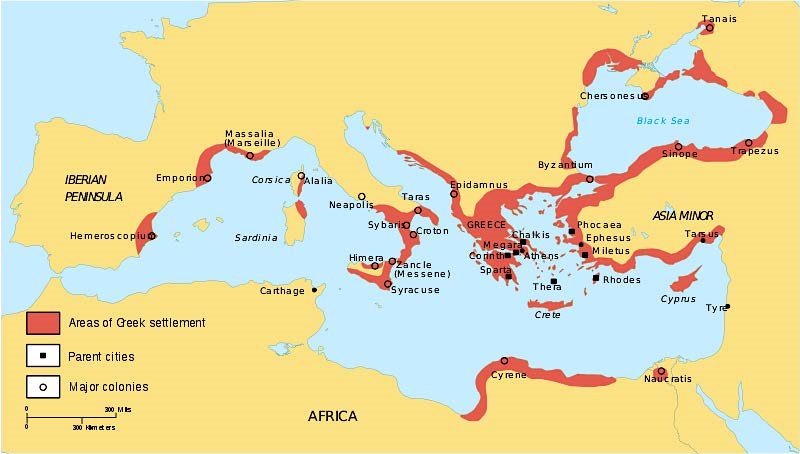

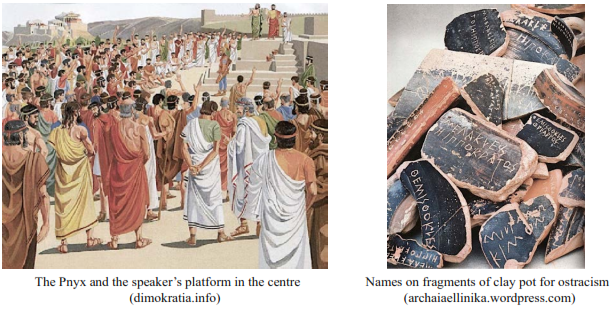

As a reaction to the overpopulation, economic problems and rising political tension, many left the mainland by ship once again to establish new colonies. Commerce and the arts thrived, as the colonies were multiplying throughout the Mediterranean. An important consequence of Greek colonisation was the spread of Greek culture, religion, art and design throughout the Mediterranean, including sites, that would come to great importance later in history.

Even more important than that, the rising distaste for tyrants and their behaviour shaped the strong political will among the Greeks to develop a more efficient and fair system of governance, which eventually led to the Athenian Democracy.

Greek colonisation in the Archaic period (commons.wikimedia.org)

The political problems in Athens were enormous. The aristocracy was only interested in maintaining its birth-right power, the newly rich class of the traders and the craftsmen was questioning that authority seeking political rights, while the impoverished farmers were demanding to erase their debts and get their freedom and land back. Most importantly they were requesting to form written laws, in order to prevent the aristocracy from exercising arbitrary power.

In 624 B.c. the aristocrats, in order to defuse the situation, asked Drako to serve as a legislator and replace the prevailing system of oral law by a written code. His laws were written in marble plates and were put in the ‘Agora’, the social, cultural, political, financial and administrative centre of the city, so everybody could see them. His laws were extremely harsh, as the death penalty was brutally used for most offences. As Aristotle says in his Politics “there is nothing in his laws, that is worthy of mention, except their severity in imposing heavy punishment” and Plutarch commented, that his laws were written with blood, not ink. Apart from his laws, Drako also made political and social reforms. The Athenian state was administered by nine Archons, rulers, appointed or elected annually by the ‘Areios Pagos’, the Supreme court, on the basis of noble birth and wealth. The Areios Pagos was an aristocratic institution composed also of men, who were of noble birth and held office for life. According to Drako Athenian citizen was hereafter not only the aristocrats, but everyone, who could afford to carry weapons for the protection of the city. He also assigned custodial role to the Supreme Court in order to assure, that the officials govern according to the law, that the laws were forced and effected and to protect anyone, who reported injustice. Unfortunately, Drako’s laws mainly served the interests of the aristocracy failing to bridge the social gap. He didn’t alter the terms of lending to prevail the farmers from losing their freedom, neither proceeded he to redistribution of the land.

The way out of this predicament came in 594 B.c with the politician, law giver, poet and one of the seven wise men, Solon. His legislation is considered the first step towards the democratisation of Athens. The most notable change implemented by Solon was the ‘Seisachtheia’, the ‘shaking-off-of-burdens’. This decree cancelled debts, banned the use of one’s own self as security for a loan and recalled all of those, who had been sold as slaves and those, who had fled to escape such a fate.

He then stated, that the nine Archons will be randomly chosen from a number of candidates, that got elected, ten from each tribe. He divided the people into four classes based on their annual income with specific rights and responsibilities. There was an assembly of Athenian citizens, the ‘Ecclesia’, but until then only the top three classes were admitted and its deliberative procedures were controlled by the nobles. Solon legislated for all citizens to be accepted into the Ecclesia. He also instituted the ‘Council of Four Hundred’ of men chosen randomly above the age of 30, that they were subjected to fines depending their income, if they didn’t fulfil their obligations. Moreover, he maintained the Supreme court and founded the ‘Heliaia’, a court with 6000 members to be formed from all the citizens, in order to achieve more objective justice. Finally, he enacted a new law, if someone was conspiring to overthrow the government, to be prosecuted and he also granted immigrants craftsmen citizenship, as well as he introduced the right of third-party appeal. However, some scholars have doubted, whether Solon actually included the lowest class in the Ecclesia, this being considered too bold move in the archaic period and some other have doubts also, if he is in fact the creator of the Council of Four Hundred. There is consensus though, that Solon lowered the requirements in terms of financial and social qualifications, which applied to be elected to public office.

The Seven Wise Men of ancient Greece, Bias of Priene, Pittacus of Mytilene, Solon of Athens, Periander of Corinth, Thales of Miletus, Cleobulus of Lindos, Chilon of Sparta. It was still a primeval time, when societies were swept up by gods and demi-gods. These Wise men shook the Greek world to the core destroying the enticement of the supernatural folktales. Their descendants honoured them by curving their names in Apollo’s sanctuary in Delphi as a reminder, who were the men, that tamed the superstitions and launched a new are for the humankind. Poet Pindar even claimed, that they were not humans, but sons of the Sun, as they cast their glow to the ends of the Greek world.

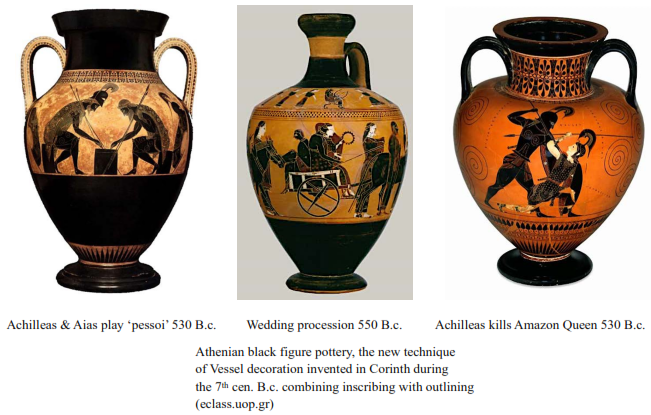

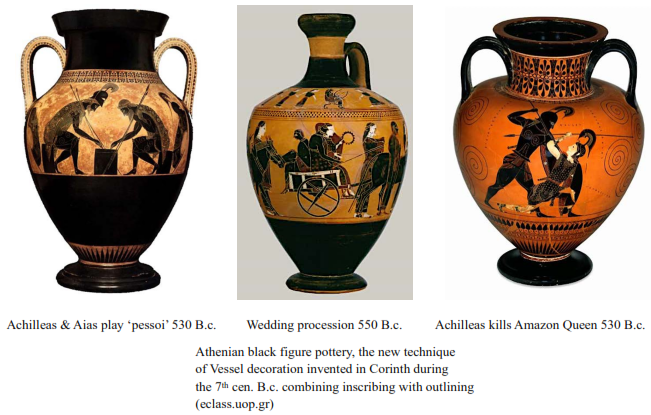

Solon reformed also the standard of weights and measures promoting the competitiveness of Athenian commerce, he minted new Athenian coinage on a more universal standard and forbade the export of produce other than olive oil, which was produced in Athens in abundance. That can be understood as a relief measure for the benefit of the poor, as it kept the prices on low levels. These economic reforms succeeded in stimulating foreign trade. Athenian black figure pottery was exported in increasing quantities and good quality throughout the Aegean between 600 B.c. to 560 B.c. According to Herodotus he left Athens for ten years, so that he could not be pressured into changing these laws. He went to Egypt, where he wrote political poems. Unfortunately, none of the social classes was satisfied. The rich lost part of their power, while their demands continued to impinge on farmer’s rights. And although the peasants got relieved from the fear of enslavement, they didn’t succeed on the redistribution of the land.

Indeed, Solon’s legislation remained in effect, but amongst the political parties, he had tried to conciliate, conflict broke out worse than ever. This unstable situation was taken advantage by the tyrant Peisistratus. Seemingly he possessed some qualities, he was popular and generous with the poor people, but he presented himself ostentatiously humble and judicious. Being cunning, especially in politics, allows one to combine the mutually incompatible, vanity and moderation. The majority of the population of the lower strata, the illiterate and unwitting, were the more susceptible to an ambitious, manipulative leader. By inflicting a wound to himself, Peisistratus convinced the governance, that he needed a personal guard supposedly to protect himself from his opponents. Solon realising the danger tried to warn his fellow citizens, if they would grant Peisistratus’ request, they would lose their freedom. Peisistratus took the power by seizing Acropolis 32 years after Solon’s legislation.

Solon tried to overthrow the usurper in agora, but no one assisted him out of fear. In despair he returned home, hung his weapons outside his door and in good conscience he uttered “I helped my country and the laws as much as I could”. When the Athenians later complained for their sufferings, he replied bitterly “If disasters befell you due to your cowardice, do not ascribe part of them to the gods, because you made them (the tyrants) powerful, since you gave them support, and because of that you fell into humiliating enslavement.” Solon envisioned to make his countrymen competent to govern their city themselves, while Peisistratus wanted to dominate patronising his countrymen.

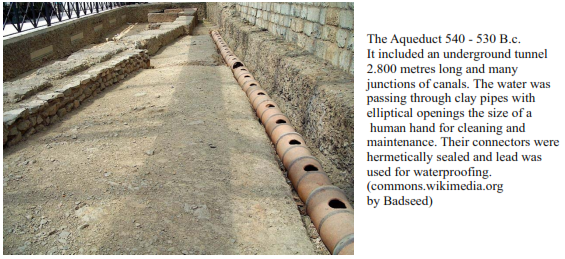

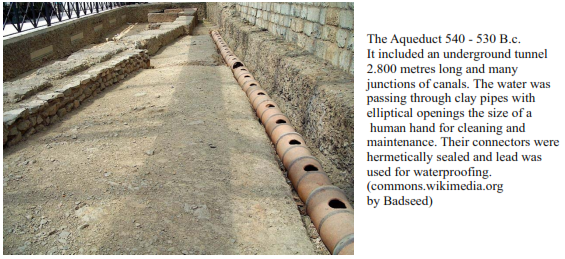

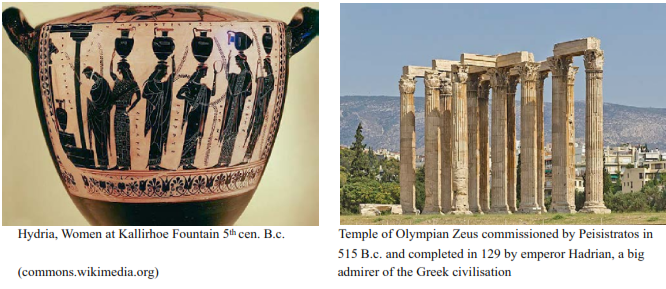

Although a tyrant, he governed with relative moderation. His career shows persistence, dexterity and diplomatic ability. However, he didn’t hesitate to take extreme and despotic measures, when needed, such as sending his opponents into exile, keeping their family hostages and confiscating their assets. He followed a program, that pleased the city’s population and parallel appealed to the rural majority. Peisistratus often tried to distribute power and benefits rather than hoard them, with the intent of easing stress between the economic classes. His main policies were aimed at strengthening the economy and like Solon, he was concerned about both agriculture and commerce. He offered land and loans to the needy. Mostly to keep them satisfied minding their own business away from the city and the politics. He instituted a system of travelling judges to provide state trials of rural cases on the spot, while he himself made inspection tours. He instated 10 % tax on the crop and he encouraged the cultivation of olives and the growth of Athenian trade, finding a way to the Black Sea, Italy and France. Under Peisistratus, fine Attic pottery travelled to Ionia, Cyprus and Syria. Protector of the art he adorned Athens with numerous monuments, which provided jobs to people in need, while simultaneously made the city a cultural centre. His internal policies appear to have been designed to increase the unity and majesty of the Athenian state. He replaced the private wells of the aristocrats with public fountain houses. Peisistratus also built the first aqueduct in Athens, opening a reliable water supply to sustain the large population.

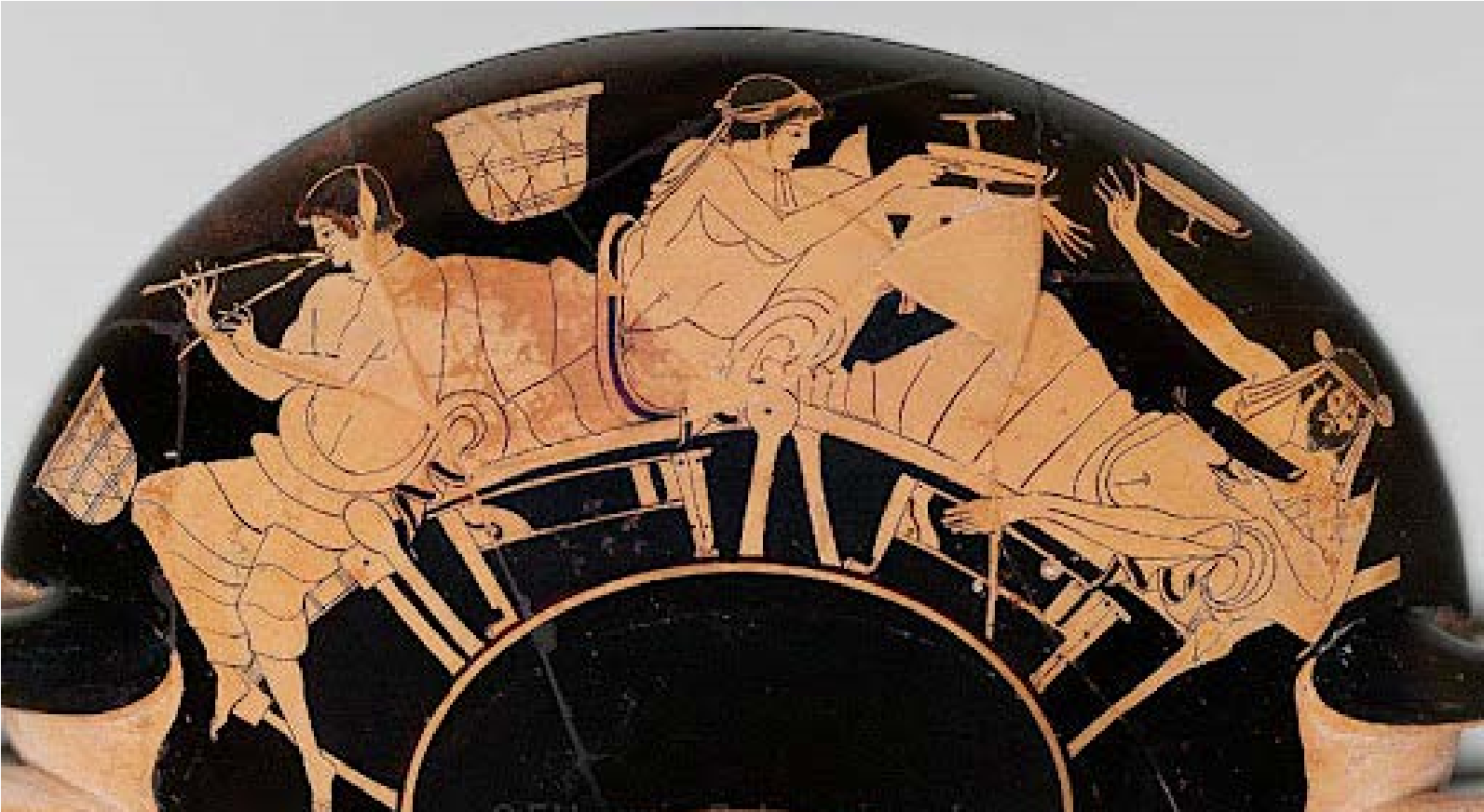

He founded the first public library and he commissioned the permanent copying and archiving of Homer’s epic poems, Iliad and Odyssey. He instituted the ‘Great Panathenaea’, a festival with athletic contests and prizes for bards, who recited the Homeric epics and the ‘Great Dionysia’ in honour of god Dionysus, where in 534 B.c. occurred the first official performance of Tragedy by the poet Thespis.

After Peisistratos’ death the city faced new political conflicts, until Cleisthenes became in 507 B.c. the protector of the people and the leader of the democrats. Undermining the power of the aristocracy he founded the Democracy of Athens (demos = people + crato = rule) and he introduced the concept of ‘Isonomia’ in the political arena, equality for all in the name of the law and before the law. That constitutes one of the most remarkable innovations of the Greeks. For the first time people conceived the idea of taking matters into their own hands, for the first time they realised, they can be in charge of their own life, for the first time they were not in the mercy of some unscrupulous king and priest in the name of some imaginative god.

Cleisthenes’ reforms aimed at breaking the power of the aristocratic families, replacing regional loyalties and factionalism with pan-Athenian solidarity and at preventing the rise of another tyrant. The full promise of the reforms could not be realised, unless the principle of hereditary privilege was attacked at the roots. So, the biggest reform he made, was to the tribal system. Previously there had been four tribes based on family ties. Cleisthenes changed this to ten tribes, each formed by a slightly complicated subsystem. This all meant, that the family ties and allegiances, that had caused before political friction, had been broken up.

He modified the Council of Four Hundred into a Council of Five Hundred, fifty members from each tribe. They were in charge to propose legislations to the Ecclesia, people’s Assembly, in order to be discussed and further approved or not. The Ecclesia could also now alter a death penalty decision of the Supreme Court.

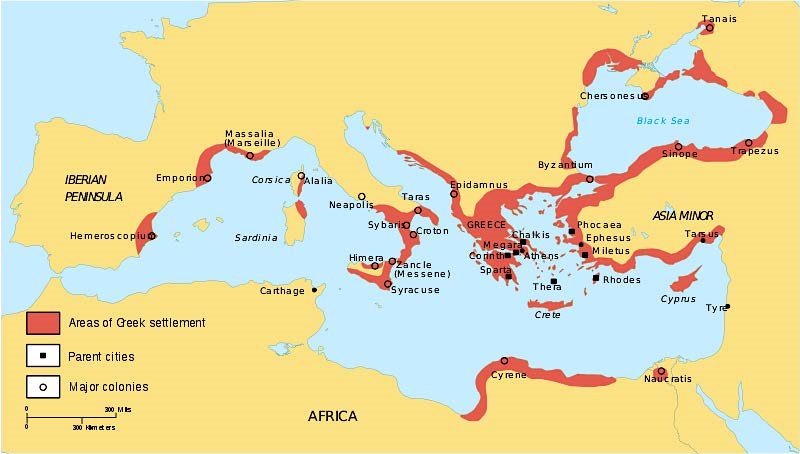

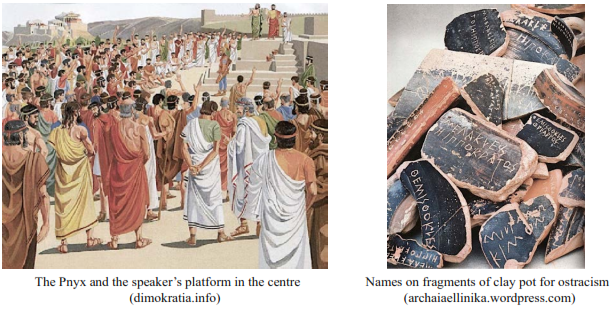

In order to protect Democracy and prevent the possibility of a tyranny to ever be reinstated, he removed the Chief Archon from head of the state and he appointed instead one of the Five Hundred, who was chosen randomly to serve just for the day. He also established the institution of ostracism, to discourage ambitious citizens from wanting to become tyrants. The Athenians could write on a fragment of a clay pot, ostracon, the name of a person, that on their opinion could impose a threat to Democracy. If a person would gather a specific number of votes, then he would have to leave the city for a decade.

Over the years that followed, any inequalities left behind by Cleisthenes were erased by the Ecclesia, which became the sovereign governing body of Athens with authoritative jurisdictions. Every adult, male, Athenian citizen was welcomed to attend the meetings of the Ecclesia. They were held 40 times per year in a hillside auditorium west of the Acropolis called ‘Pnyx’ and everyone had a say in the decision-making process on decrees, that affected every aspect of Athenian life, both public and private, from financial matters to religious ones, from public festivals to war, from treaties with foreign powers to various regulations. Citizens were paid for attending the Ecclesia, to ensure, that even the poor could afford to take time from their work to participate in their own government. Individuals could lose the right to participate by committing various offences.

Athens was the first example of direct Democracy, where people did not elect representatives to take decisions on their behalf, but they had legislative and administrative power themselves. The limited population and the small distances assisted on that. They considered the elections an aristocratic constitution, that always favours the rich, the nobles and the famous, therefore they preferred a lottery selection process, which was the only way to prevent corruption. People enjoyed a unique form of political equality, when in the rest of the world it was a common belief, that people are born and die in the same status. No one should nor could escape.

There was also necessary to appoint some officials for a restricted period of time, who could be revoked at any given moment. All citizens had the opportunity to serve in these positions only once, in some cases twice. They had certain responsibilities and limited spectrum of initiative. They were rather coordinating, than actual ruling. As they were not taking any decisions in the name of the people, they were just acting based on the decisions already taken by the people’s Assembly. Before a citizen took over a position, he was assessed on his capabilities and after he had served the city, he was evaluated on his performance. If he harmed the city in any way, he would have to pay the price.

There were also some officials elected like the Ten Generals, due to the experience needed in military affairs, as well as those, who were handling large amounts of money. They could be removed from their position, if necessary and they were facing severe punishments in case of abuse of power or embezzlement, such as huge fines, loss of fortune, loss of political rights, exile, even death. The lack of interest and will to participate in the state’s affairs was treated with contempt by the Athenians. Such individuals were called ‘idiotis’ meaning someone, who has only private life with no interest for the public matters. Today that word is detected in many languages as ‘idiot’ with equally degrading connotation.

The principal of the Ecclesia was the freedom of speech. Of course, some people might be better qualified than others to speak on certain subjects and the citizens of Athens could be very critical, when anyone tried to speak outside of his expertise. But as Socrates states, “When the discussion is not about technical matters but about the governing of the city, the man, who rises to advise them on this, may equally well be a smith, a shoemaker, a merchant, a sea-captain, a rich man, a poor man, of good family or of none”. Everyone could speak freely, explain and try to convince the other with arguments. That was the pride of Athens. And that is what differentiates radically the Greeks from all the rest. The exercise of power becomes everybody’s responsibility. Who had ever before expressed similar ideas? In which part of the world? Everywhere else people praised the divine grandiosity of their rulers and the god-inspired wisdom of their priests or prophets. This unique, revolutionary, unexpected vision of the world is Greek and the formulation of its terms, Athenian.

In this prolific environment flourished great ideas, that changed the world, such as ‘Isonomia’, egalitarianism, ‘Isopoliteia’, equal access and chance to participate in public axioms, ‘Isigoria’, freedom of speech in the people’s Assembly, ‘Parresia’, express of opinion freely, blatantly, proudly with courage and honesty. Such an environment inspired the great accomplishments of the Greek civilisation in literature, art, architecture and most predominately in philosophy. The ideals of fairness, virtue, ethos surpassed the ugliness in the world and the spiritual excellence was far superior than the social, economic and technological advancements. The human, that was glorified with every opportunity, was the complete human being, the one, that loved refined life and cherished high aesthetics, enjoyed celebrations and symposiums, that sought romance and pursued glory, the one, that possessed passion for the art of dialogue, communication through analyses and logical arguments. That doubtless is the most remarkable quality of Hellenism.

Bravery, philopatry, tolerance, law, these are the foundations of Democracy. Above all, law meant the opposite of violence and was conceived to work as its antidote. Greeks never ceased to rise against violence. They hated war, arbitrariness, disorder, but most predominately they feared civil strife. Ares, the god of war, was horrifying even Zeus himself. The act of war was condemned all over the Greek literature. It is evident in Herodotus “Because no one is so fool to prefer war instead of peace, when in the latter the children bury the father, while during war the fathers bury their children”. It is evident in Euripides, when the herald states, that people in their madness chase wars and enslave the weaker, one man the other, one city the other city. Greeks could clearly discern, that war itself was unacceptable. It was like whole Greece was mobilised against violence and that exactly inspired the fiery, passionate respect towards the law. Persuasion opposes violence too and as a result of the free dialogue, constitutes a cornerstone of Democracy. To make someone understand a point of view and agree in a free manner, that was the motivation of this Democracy, of which the Athenians were so proud, leaving the coercion to the kings and the tyrants.

Not only. They reached even further. Surely, they discovered the basic principal for agreements, arbitrations, treaties, alliances, federations and confederacies and although they didn’t manage to unite, they clarified, what should be avoided and which terms should be honoured. Still, all the above are part of arrangements and laws. What about all those, that no treaty, no written obligation was protecting them? And here comes the unwritten law for everything, that lied beyond the jurisdiction of the law. Like the respect towards the suppliants and the heralds, the burial of the dead and the help to the ones that suffer. Very often the unwritten law was regarded as common law for all the Greeks. Their effort for catholicity helped them distinguish, which human traits are universal and precisely this universality of the human condition, features prominently in the Greek thinking and inundates every form of literature. Even more, they conceived the idea of empathy, the ability to understand and feel, what another person is experiencing and the capacity to place oneself in another’s position. Odysseus in Sophocles’ tragedy refuses to ridicule his rival, because he identifies with his position and sympathises with him. “I feel sorry for him, although he is my enemy, because, poor him, he is in a dreadful ill. I don’t just worry about his fate only, but about mine as well, as I clearly see that we, the living, we are nothing but hollow shadows, shades and breeze”.

Already Homer had introduced the concept of mortality, which led to the realisation of the human fate. The Greeks stated the fact, that there is a definite death, conclusive and final. No one can alter it nor beautify it. They are the only ones calling the man ‘broto - morto’ hence mortal. The world wasn’t made by a numinous, merciful force for the sake of the people. Even gods themselves are subjected to some invisible fate, that at the moment, places them in power, but relentlessly can send them into nothingness. The idea of life after death as such doesn’t exist and, in any case, it is worse than life on earth. Achilleas says to Odysseus, that he would rather be subordinate to a peasant, than rule in the kingdom of the dead. Existence is subjected to the law of nature, birth is followed by decline. The Greek world is built on the knowledge and acceptance of death, on the awareness, that there is no other life and whatever needs to be done, has to be done now. That resulted to the birth of another admirable merit, that of the philanthropy, which originally meant the love and concern for humans and their fate, which today is called humanism.

Athenian Democracy was a governing solution, that corresponded with the conditions in the city of Athens. It was supported mostly by farmers with just a small piece of land or totally landless, who formed the working class. The upper class of land and slave owners were mostly against this political innovation. Many throughout the time have also opposed, as Democracy can turn into ochlocracy, rule by a disorder crowd. Aristotle for example considered Democracy a deviation and classified it amongst the worst political systems along with tyranny, while Lenin viewed it as a negative phenomenon, since the minority was oppressed by the majority. Many also point out, that the Athenian Democracy didn’t abolish slavery, kept women outside the public life and was thrifty towards offering the immigrants political rights.

As far as it concerns slavery, according to the technological conditions at that time, no society could refrain from using slaves in the production process. Obviously that stalled Athenians from ending slavery, something that took thousands of years for the rest of the world to nearly accomplish. Martin Luther King leader in the African American civil rights movement was assassinated in 1968 in Memphis, Nelson Mandela served 27 years in prison for fighting apartheid in South Africa, a system of racial segregation, that privileged whites, and got released only in 1990 and so many others. Even worse, although today slavery isn’t legal anywhere, yet in the 21st century still exists almost everywhere including Europe and the United States. Researchers from the International Labour Organisation estimate that 21 - 30 million are enslaved worldwide, generating $150 billion each year in illicit profits for traffickers. About 78 % toil in forced labour slavery in industries, where manual labour is needed, such as farming, ranching, logging, mining, fishing, brick making and in service-industries working as dish washers, janitors, gardeners and maids, while 22 % are trapped in forced prostitution sex slavery. About 26 % of today’s slaves are children.

As far as it concerns the position of the women, the Athenians were mostly at home, unless they were participating in some celebrations or religious practices. In many cases though the women had some form of freedom and financial independence. The married woman, when her husband was busy at work or with the public affairs, was in charge with absolute authority of the house. When the husband was away, she had to take care of everything and the widower was handling the fortune till the children reached adulthood. The women also of the upper class enjoyed more freedom.

Nevertheless, it took thousands of years for women to win their rights and to achieve emancipation, at least in some parts of the world. Finnish women were the first in the world fully to exercise the right to vote and to stand as a candidate in elections just only 100 years ago in 1906, while in December 2015 took place the first municipal election in Saudi Arabia, in which women were allowed to vote, the first in which they were allowed to run for office and the first in which women were elected as politicians. But as women in Saudi Arabia are not permitted to address men, who are not related to them, female candidates could only speak directly to female voters. At men’s campaign meetings, they had to either speak from behind a partition, or have a man read their speech on their behalf.

Alas women today continue to suffer oppression and physical, sexual or psychological abuse. In the majority of cases the abuse is committed by the people they love and trust the most, their families. Young girls are forced into marriages with old men, women are mutilated, because supposedly they have violated the family’s honour, or tortured by the husband and the in-laws by pouring hot oil over their head, because they were not subordinate enough or simply they are not allowed to leave their homes without a male relative or be seen in public without a burqa. For defying the regime’s repressive laws, women are openly flogged and executed. Moreover, women are subjected to female genital mutilation (FGM), which includes procedures, that intentionally alter or cause injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons. These procedures have no health benefits for girls and women, on the contrary they cause severe pain and bleeding, shock, problems urinating and later cysts, infections, as well as complications in childbirth and increased risk of newborn deaths, even death through severe bleeding leading to haemorrhagic shock. More than 200 million girls and women alive today have been cut in 30 countries in Africa, the Middle East and Asia. FGM is recognised internationally as a violation of the human rights of girls and women. It reflects deep-rooted inequality between the sexes and constitutes an extreme form of discrimination against women. It is nearly always carried out on minors and is a violation of the rights of children. The practice also violates a person’s rights to health, security and physical integrity, the right to be free from torture and cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment, and the right to life, when the procedure results in death. (World Health Organisation)

If we add on that list customs and rituals such as foot binding or neck elongating, then we realise how much women have been abused, violated in every possible aspect and objectified through the history.

Foot binding was the custom of applying painfully tight binding to the feet of young girls to prevent further growth. Women, their families and their husbands took great pride in tiny feet, with the ideal length of 10 cm, called the ‘Golden Lotus’. It became popular as a means of displaying status, as women from wealthy families, who did not need their feet to work, could afford that custom, it was adopted as a symbol of beauty in Chinese culture and was also a prerequisite for finding a husband, so eventually it spread to all the classes. Walking on bound feet necessitated bending the knees slightly and swaying to maintain proper movement and balance, a dainty walk, that was considered erotic to some men. In reality, the underlying appeal was explicitly sexual. Crippled feet required one to walk in a certain mincing manner to avoid toppling over. As a result, it