( 15 )

THE DIET SODA

DELUSION

ON A WARM June night in 1879, the Russian chemist Constantin Fahlberg sat down to dinner and bit into a remarkably sweet roll of bread. What was remarkable was that no sugar was used to make it. Earlier that day, while working on coal-tar derivatives in the laboratory, an extraordinarily sweet experimental compound had spilled all over his hands, and then made its way into the rolls. Rushing back to the laboratory, he tasted everything in sight. He had just discovered saccharin, the world’s first artificial sweetener.

THE SEARCH FOR SWEETENERS

ORIGINALLY SYNTHESIZED AS a drink additive for diabetics, saccharin’s popularity slowly spread,1 and eventually other sweet, low-calorie compounds were synthesized.

Cyclamate was discovered in 1937, but later removed from use in the United States in 1970 due to concerns about bladder cancer. Aspartame (NutraSweet), was discovered in 1965. Approximately 200 times sweeter than sucrose, aspartame is one of the most notorious of sweeteners, due to its cancer-causing potential in animals. Nevertheless, it gained approval for use in 1981. Aspartame’s popularity has since been eclipsed by acesulfame potassium, followed by the current champion, sucralose. Diet soda is the most obvious source in our diet of these chemicals, but yogurts, snack bars, breakfast cereals and many other “sugar-free” processed foods also contain them.

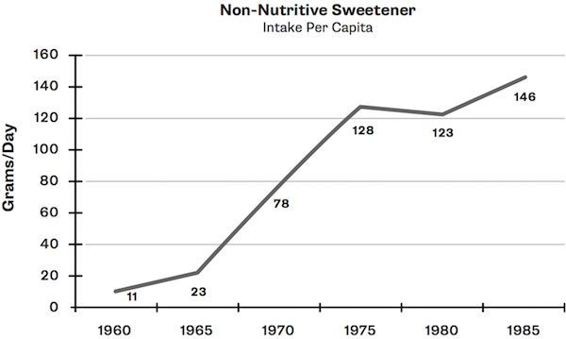

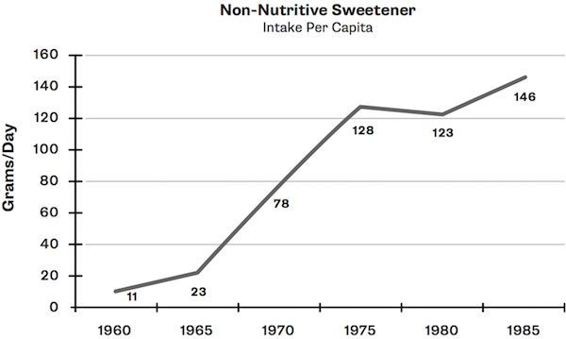

Diet drinks contain very few calories and no sugar. Therefore, replacing a regular soft drink with a diet soda seems like a good way to reduce sugar intake and help shed some pounds. With the increasing health concerns around excess sugar, food manufacturers responded by releasing an estimated 6000 new artificially sweetened products. The intake of artificial sweeteners has increased markedly in the U.S. population (see Figure 15.1) 2 with 20 percent to 25 percent of American adults routinely ingesting these chemicals, mostly in beverages.

Figure 15.1. Per capita consumption of artificial sweeteners increased more than 12-fold between 1965 and 2004.

From humble beginnings in 1960 to the year 2000, the consumption of diet soda has increased by more than 400 percent. Diet Coke has long been the second most popular soft drink, just behind regular Coca Cola. In 2010, diet drinks made up 42 percent of Coca Cola’s sales in the United States. Despite initial enthusiasm, though, the use of artificial sweeteners has recently leveled off, primarily due to safety concerns. Surveys indicate that 64 percent of respondents had some health concerns about artificial sweeteners, with 44 percent making a deliberate effort to reduce their intake or avoid them altogether.3 And so the search has been on for more “natural” low-calorie sweeteners.

Agave nectar enjoyed a brief surge of popularity. Agave nectar is processed from the agave plant, which grows in the southwest regions of the United States, Mexico and parts of South America. Agave was felt to be a healthier alternative to sugar due to its lower glycemic index. Dr. Mehmet Oz, a cardiologist popular on American television, briefly touted the health benefits of agave nectar before reversing his stance when he realized it was mostly fructose (80 percent).4 Agave’s low glycemic index was simply due to its high fructose content.

The next big thing to hit the market was stevia. Stevia is extracted from the leaves of Stevia rebaudiana, a plant that is native to South America. It has 300 times the sweetness of regular sugar and a minimal effect on glucose. Widely used in Japan since 1970, it has recently become available in North America. Both agave nectar and sweeteners derived from Stevia are highly processed. In that regard, they are not any better than sugar itself—a natural compound derived from sugar beets.

THE SEARCH FOR PROOF

IN 2012, BOTH the American Diabetes Association and the American Heart Association issued a joint statement5 endorsing the use of low-calorie sweeteners to aid in losing weight and improving health. The American Diabetes Association states on its website, “Foods and drinks that use artificial sweeteners are another option that may help curb your cravings for something sweet.”6 But the evidence is surprisingly scarce.

Presuming that artificial low-calorie sweeteners are beneficial presents an immediate and obvious problem. Per capita consumption of diet foods has skyrocketed in recent decades. If diet drinks substantially reduce obesity or diabetes, why did these two epidemics continue unabated? The only logical conclusion is that diet drinks don’t really help.

There are substantial epidemiologic studies to back that up. The American Cancer Society conducted a survey of 78,694 women,7 hoping to find that artificial sweeteners had a beneficial effect on weight. Instead, the survey showed exactly the opposite. After adjustment for initial weight, over a one- year period, those using artificial sweeteners were significantly more likely to gain weight, although the weight gain itself was relatively modest (less than 2 pounds).

Dr. Sharon Fowler, from the University of Texas Health Sciences Center at San Antonio, in the 2008 San Antonio Heart Study8 prospectively studied 5158 adults over eight years. She found that instead of reducing the obesity, diet beverages substantially increased the risk of it by a mind-bending 47 percent. She writes, “These findings raise the question whether [artificial sweetener] use might be fueling—rather than fighting—our escalating obesity epidemic.”

The bad news for diet soda kept rolling in. Over the ten years of the Northern Manhattan Study,9 Dr. Hannah Gardener from the University of Miami found in 2012 that drinking diet soda was associated with a 43 percent increase in risk of vascular events (strokes and heart attacks). The 2008 Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study (ARIC) 10 found a 34 percent increased incidence of metabolic syndrome in diet soda users, which is consistent with data from the 2007 Framingham Heart Study,11 which showed a 50 percent higher incidence of metabolic syndrome. In 2014, Dr. Ankur Vyas from the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics 12 presented a study following 59,614 women over 8.7 years in the Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study. The study found a 30 percent increase risk of cardiovascular events (heart attacks and strokes) in those drinking two or more diet drinks daily. The benefits for heart attack, stroke, diabetes and metabolic syndrome were similarly elusive. Artificial sweeteners are not good. They are bad. Very bad.

Despite reducing sugar, diet sodas do not reduce the risk of obesity, metabolic syndrome, strokes or heart attacks. But why? Because it is insulin, not calories, that ultimately drives obesity and metabolic syndrome.

The important question is this: Do artificial sweeteners increase insulin levels? Sucralose 13 raises insulin by 20 percent, despite the fact that it contains no calories and no sugar. This insulin-raising effect has also been shown for other artificial sweeteners, including the “natural” sweetener stevia. Despite having a minimal effect on blood sugars, both aspartame and stevia raised insulin levels higher even than table sugar.14 Artificial sweeteners that raise insulin should be expected to be harmful, not beneficial. Artificial sweeteners may decrease calories and sugar, but not insulin. Yet it is insulin that drives weight gain and diabetes.

Artificial sweeteners may also cause harm by increasing cravings. The brain may perceive an incomplete sense of reward by sensing sweetness without calories, which may then cause overcompensation and increased appetite and cravings.15 Functional MRI studies show that glucose activates the brain’s reward centers fully—but not sucralose.16 The incomplete activation could stimulate cravings for sweet food to fully activate the reward centers. In other words, you may be developing a habit of eating sweet foods, leading to overeating. Indeed, most controlled trials show that there is no reduction in caloric intake with the use of artificial sweeteners.17

The strongest proof of failure comes from two recent randomized trials.

Dr. David Ludwig from Harvard randomly divided two groups of overweight adolescents.18 One group was given water and diet drinks to consume while the control group continued with their usual drinks. At the end of two years, the diet soda group was consuming far less sugar than the control group.

That’s good—but that is not our question. Does drinking diet soda make any difference to adolescent obesity? The short answer is no. There was no significant weight difference between the two groups.

Another shorter-term study involving 163 obese women randomized to aspartame did not show improved weight loss over nineteen weeks.19 But one trial20 involving 641 normal-weight children did find a statistically significant weight loss associated with the use of artificial sweeteners. However, the difference was not as dramatic as hoped. At the end of eighteen months, there was only a 1-pound difference between the artificial sweetener group and the control group.

Conflicting reports such as these often generate confusion within nutritional science. One study will show a benefit and another study will show the exact opposite. Generally, the deciding factor is who paid for the study. Researchers looked at seventeen different reviews of sugar-sweetened drinks and weight gain.21 A full 83.3 percent of studies sponsored by food companies did not show a relationship between sugar-sweetened drinks and weight gain. But independently funded studies showed the exact opposite— 83.3 percent showed a strong relationship between sugar-sweetened drinks and weight gain.

THE AWFUL TRUTH

THE FINAL ARBITER, therefore, must be common sense. Reducing dietary sugars is certainly beneficial. But that doesn’t mean that replacing sugar with completely artificial, manmade chemicals of dubious safety is a good idea. Some pesticides and herbicides are also considered safe for human consumption. However, we shouldn’t be going out of our way to eat more of them.