CHAPTER XII

UP AND DOWN GUATEMALA

I

From Tapachula to the Guatemalan border, there was a train every two or three days, provided traffic warranted so much service.

It took me through a bamboo forest, and dropped me at Suchiate, a straggling village of thatched huts beside a muddy river, where I had my first experience with the formalities attendant upon the crossing of a Central-American frontier.

First one had to secure permission from the Mexican authorities to leave their country. In a whitewashed shed three leisurely gentlemen in their shirt sleeves were viséing passports. Before they would proceed, one had to obtain stamps, procurable only at another shack, located as always in these countries at the opposite end of town, and reached by trudging through deep sand beneath a broiling sun. And when, after half an hour or more, one returned with the stamps, there were questions:

Why were we leaving Mexico? When? Where were we going? Why? What had we done in Mexico? Why the devil had we come there, anyhow? What was our profession? Married or single? How many children? Why? Where were they? And how?

And when one had convinced the officials of his respectability, there was another long hike across an endless sunny grass-plain, to a palm-thatched shelter at the river bank, where other officials ransacked the baggage. A boatman poled the few emigrants across the swirling waters to Guatemala. And the entire proceeding recommenced on the other side.

The Guatemalan officials had no office. They stood in the shade of a pepper tree, flanked on one side by a squad of barefooted soldiers, on the other by an ox-cart, and backed by the town’s juvenile population. They pretended very solemnly to read every word in the passports—although one traveler’s was in Russian and another’s in Syrian. They paused now and then to shake their heads doubtfully and exchange suspicious glances. But at length, when every one had proved his solvency by displaying thirty-five dollars in American currency—Guatemalan bills not being considered sufficient proof of solvency—they passed us all. Baggage was loaded upon the ox-cart, and we started for the custom-house, led by the soldiers, and followed by the juvenile population.

There was another wait of more than an hour while the custom inspector finished his lunch, took his siesta, and smoked his cigarette. At last, however, he made his appearance, scribbled in chalk all over the outside of trunks and suit-cases, filled out several printed reports, and collected from each of us ten Guatemalan dollars—or fourteen cents in American money—and the formalities were concluded.

We were officially admitted to the Republic of Guatemala.

II

From Ayutla, the Guatemalan frontier station, to Guatemala City was another day’s ride.

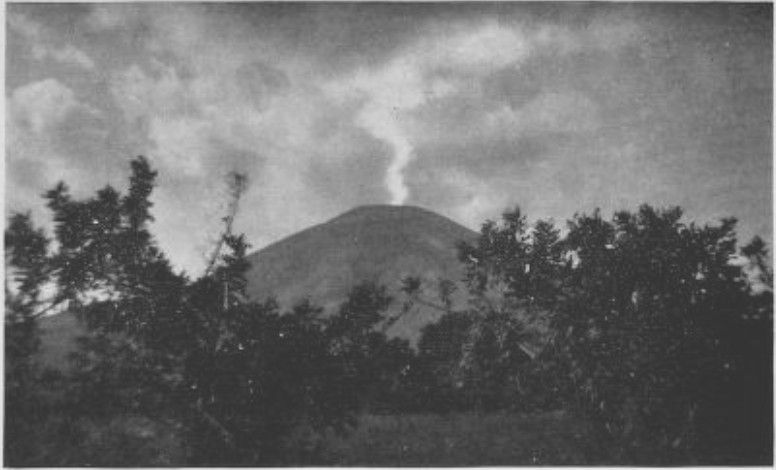

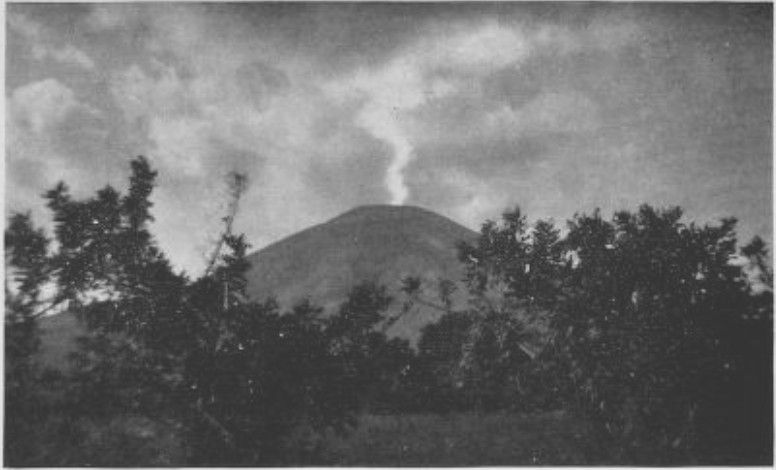

The railway coaches, if possible, were just a trifle more dilapidated than those of Mexico, but the train made better time. The way led through a continuation of the bamboo forests, but it soon rose to the cooler highlands, where volcanic cones towered into the clouds. One or two of the craters were smoking, filling the sky with dense masses of white vapor, and sprinkling the earth with a fine lava dust.

To all Central America, these volcanoes are blessings. Occasionally the attendant earthquakes may shake down a city, but the lava dust enriches the soil, and a good coffee crop provides the wherewithal for reconstruction. The Pacific slopes of Guatemala are exceedingly fertile. Coming from Mexico, where revolution had brought a cessation of work, one noticed the air of prosperity in this little Central American country. The hills everywhere were red with coffee berries, the plantations were neatly kept, and the peons all seemed busy.

THE ABUNDANT CENTRAL-AMERICAN VOLCANOES FERTILIZE THE COFFEE FINCAS WITH LAVA DUST

They were very small, these Guatemalan Indians, so small that they suggested Lilliputians, but remarkably sturdy. They appeared to earn their living principally by carrying bundles. Every woman on the road was galloping along with swift, flat-footed stride, swinging her arms as though paddling her way, balancing on her head a basket of produce or a great cluster of earthenware jars. Every man had a load upon his back, sometimes so much larger than himself that he resembled a tiny ant struggling beneath a huge beetle. He supported his burden with straps over his shoulders, and with a band about his forehead, so that by inclining his neck forward or back, he could shift the weight. These people showed no bulging muscle; theirs was the smooth modeling of the Indian physique that concealed tremendous strength. They seemed never to pause for rest, but trotted untiringly, serving as pack-animals in the more remote regions for fourteen cents a day, and carrying a hundred and fifty pounds for twelve hours or more.

They were the most colorful types to be seen south of Tehuantepec. Each village had its own distinctive costume, particularly among the women. At one station they were wearing short purple jackets that disclosed six inches of bronze stomach. At another they were clad in tight blue skirts, a waist of print cloth, and a wide sash of blazing scarlet wrapped tightly about the hips. At another they were draped in serapes with a design picturing such confusion as might occur if a bolt of lightning were to become entangled in a rainbow.

Guatemala is essentially an Indian republic. Among its 2,250,000 people—who incidentally comprise forty per cent. of the total population of Central America—there are a million of pure aboriginal ancestry. The whites are comparatively scarce. Yet this is the least democratic of the local nations, and the whites dominate it completely. The greater part of the country belongs to a few wealthy landlords, either native or German, and the peon, although not mistreated, has little to say about his government. But the peon always has employment. And Guatemala is prosperous.

GUATEMALA’S POPULATION INCLUDES A MILLION PURE-BLOODED ABORIGINES

One noticed that the train did not stop long for Indians who wished to board it, as did trains in Mexico. If a wealthy hacendado were seen advancing down the road, the conductor waited for him. If two dozen barefoot passengers were at the station, the engineer tooted his whistle peremptorily, paused only for a moment, allowed them to scramble aboard as best they could, and was off again.

After Mexico, this speed was startling. Considering the size of Central-American republics, one feared lest the train overrun the boundary lines and trespass upon the sovereignty of Salvator or Honduras. But it stayed within its own domain, turning eastward, and climbing out of the coffee-covered Pacific slopes to the pine-clad heights of central Guatemala, landing us in the evening at Guatemala City, 4870 feet above the sea.

III

To the American at home, all Central America is a heat-stricken jungle. He invariably greets the returned traveler with, “I’ll bet you’re glad to get back to God’s country!” As a matter of fact, Guatemala City—like Tegucigalpa, in Honduras, and San José in Costa Rica, and some several other cities in all these countries—has a climate which no city in the United States can equal. It is pleasantly warm at mid-day, and delightfully cool at night. The traveler in these parts always pities the American at home, who freezes for six months, and sweats for six months. He never can understand why the poor fellow doesn’t let the farm go to seed, and move down to a decent climate.

IV

The Guatemalan capital is a pleasant city, but not handsome.

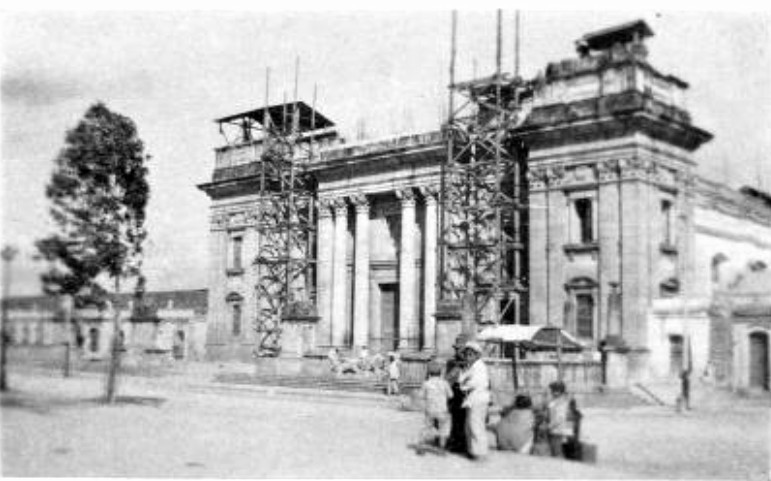

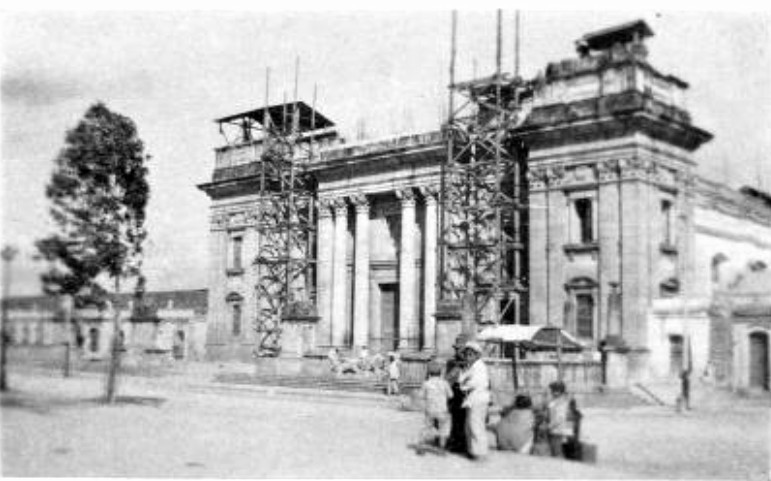

Built low and massively, it gives one the impression that it is patiently awaiting another earthquake. In its past it has been moved about from time to time in the hope that it might find a resting place free from nature’s assaults, but another tremor always finds it and shakes it to pieces. It was destroyed in 1917 and again in 1918. A writer never dares use the phrase, “The last earthquake,” since another is apt to occur before his book reaches print.

At the time of my visit, in 1924, its builders had apparently become discouraged. Many of the buildings were still but a heap of crumbled ruins. The streets were rough, paved with cobbles partially dislodged, and marked with crazy trails which traffic had worn out in years of zigzagging from curb to curb in an effort to find passage. The drivers of the little old cabs worked their way along these streets like sailors tacking through a tortuous channel, and only large automobiles were in evidence, for the smaller variety so popular in Mexico would have shaken passengers to death.

At the main plaza, the Cathedral was surrounded by piles of débris. Since Guatemala keeps the church in the same restraint as does Mexico, the Bishop could not afford to rebuild every year or two. The edifice now stood with columns seamed and cracked, with dome and towers completely gone, and with its greenish silver bells protected by improvised board shelters. The interior also presented a patched effect, and a ruined altar was replaced by a less ornate substitute, but business was proceeding as usual.

OCCASIONALLY THE RESULTANT EARTHQUAKES KNOCK DOWN A CITY OR DESTROY THE GUATEMALAN CATHEDRAL

Guatemala, however, is the largest city in Central America. Its population—estimated as accurately as anything is estimated in these parts—numbers something between a hundred and two hundred thousand. If a trifle crumbled, it is the most complete city hereabouts. There are many shops, several banks, a number of theaters, and a host of excellent hotels. There is local color in abundance, for Indians in picturesque garb walk the streets, lounge in the plaza, and congregate in the native market behind the cathedral, quite as primitive as in the rural districts. There is electric light, a system of mail boxes set into the house-walls at every corner, and even a café with an orchestra at every half block for those who crave modernity.

These cafés are really a distinguishing feature of Guatemala City. Elsewhere in Central America waitresses are usually waiters. Here the waiters are usually waitresses—rather coquettish little señoritas, whose smiles are served gratis with every order. The coffee-kings gather there nightly to keep their wealth in circulation, and to bask in the smiles. They drink somewhat immoderately, as in Mexico, and wait patiently to the closing hour, only to learn that the girls’ own parents call to take them straight home. But the coffee-kings are ever hopeful. They come back night after night. And the cafés possess a gayety that adds to the city’s attractiveness.

Neither revolution, nor earthquake, nor disappointment in love can dampen the good humor of these countries.

V

By chance, on my first evening in Guatemala City, I was held up by a highwayman.

I was rambling about unaccustomed streets, when a polite little brown gentleman stepped out of a doorway, poked a revolver into my ribs, and said courteously:

“Pardon, señor. Please to raise both the hands above the head, and to tell me in which pocket I shall find your watch and your money.”

My watch was one of those cheap things which the traveler always carries for such an emergency. My money formed a large wad, but it was all in Guatemalan currency, and I had my doubts as to whether my assailant would accept it. Back in Tapachula the Guatemalan Consul, having viséd my passport, had refused the moth-eaten bills of his own country, demanding American greenbacks, but finally compromising upon Mexican gold. The highwayman, however, was too polite to refuse.

“I thank you greatly, señor,” he said. “Again I beg your pardon, and bid you adios.”

Covering me with the revolver, he backed around a corner. When I looked to see where he had gone, he was running furiously down the dark street. He had taken a hundred and fourteen Guatemalan dollars, or about ninety cents in American coinage.

VI

In any Central-American republic, one notices a “homey” quality lacking in the larger territory of Mexico.

In these smaller nations, every one of any prominence knows every one else. The capital is something of a Latinized Main Street. This is more true of the little countries to the south, but Guatemala is not completely an exception. Its provincialism manifests itself particularly in the newspaper, which savors always of the local country weekly, although a flowery verbosity gives it a unique distinction.

In Mexico City, one finds a press quite the equal of the American, with a several-page daily edition that shows an appreciation of news values, and a Sunday edition complete even to rotogravure picture section and comic supplement. In Guatemala City one finds a little four-page sheet, published apparently by some gentleman who desires an organ for the glorification of his friends and the vilification of his enemies.

On its first page is the feature story of a party given last night by the editor’s brother-in-law, Don Guilliermo Pan y Queso Escobar, whose palatial mansion was graced by a felicitous gathering of our most illustrious men and our most charming women, truly representative of the very cream of our distinguished society, and so on with an ever-swelling multitude of flattering adjectives. Beside it is an account of the Commencement Exercises of the local stenographic college—of which the editor’s uncle is the principal—an event which seems to have been a complete success, for it was celebrated with an éclat both artistic and educational unsurpassed in the history of our city, and every number of the delightful and uplifting program was greeted by rapturous applause, the audience sitting spellbound as the estimable, virtuous, and pulchritudinous señoritas of the student body demonstrated their efficiency by taking down in shorthand, almost word for word, the speech of the director, our sympathetic and greatly admired fellow-countryman, Don Ricardo Cantando y Bailando Chavez, to whom great credit is due for the distinction and finesse with which the entire entertainment, and thus and thus, until the article closes with a list of the persons present, the illustrious and distinguished everybody in the audience who wore shoes.

On the last inside page, hidden among the advertisements, are the brief cablegrams from the rest of the world, announcing the death of Lenine, the invasion by France of the German Ruhr, and such other unimportant events as the destruction of Tokio by earthquake, the election of a new American president, or a war in Europe.

VII

Guatemala contained a large colony of foreigners. There were many Germans engaged in the coffee business on the Pacific slopes, many Americans from the banana plantations of the Caribbean Coast, a few exiled European noblemen who had come with the remnants of their former fortunes to live as long as possible without working in a country where living was cheap, and several Old-Timers, all with the rank of General, who had fought in the various past revolutions of Central America, and were now resting upon their laurels.

These countries have long been the happy hunting ground of the soldier of fortune, of whom the greatest since William Walker was General Lee Christmas, who died at New Orleans while I was at the scene of his exploits.

Christmas came to Central America as a locomotive engineer. It had been his profession in Mississippi until a wreck, followed by an investigation, brought out the fact that he was color-blind and could not distinguish signals. Central America was less strict about such things in those days. In fact, most of the old-time engineers are said to have driven their trains with a whiskey-flask handy, and with few worries about such things as signals. Christmas found employment, but he became accidentally entangled in an insurrection, and formed the habit. On one occasion, when he was driving an engine in Guatemala, he is said to have received news of an outbreak in Honduras, and to have left his train with all its freight and passengers standing on the track while he hopped out of the cab-window and hiked overland through the jungles to join the fray. His greatest exploit was that of repulsing an entire army with a machine-gun, assisted only by one other gringo, a Colonel Guy Maloney, now Superintendent of Police in New Orleans. He drifted from one country to another, wherever a fight seemed most promising, followed by troops that varied in number from two men to fourteen thousand.

“He was a good scout, too,” agreed most of the Old-Timers in Guatemala City. “He’d give you his last cent, if you needed it. He’d have been a millionaire, if he’d saved half the money he got from the governments he helped, but he blew it all in on parties. He’d get drunk with you, or he’d go down the line with you, or he’d fight you—anything to please his friends. He was pretty square, usually, when he held office. When he was Chief of Police up in Tegucigalpa, if his best pals raised the devil, he’d stick them right in jail. And when their term was over, he’d give them a whale of a good party.”

His revolutionary habits finally became so annoying to Washington that his citizenship was canceled. Broken-hearted about it, he came home, assisted the secret service throughout the European War, and was reinstated. When he fell ill from old wounds and fevers contracted in Central-American jungles, many Old-Timers cabled offers of assistance, and his old lieutenant, Colonel Guy Maloney, gave him a blood transfusion, but it was too late. When the news of his death reached Central America, more than one president probably heaved a sigh of relief.

Guatemala City was filled with other ex-adventurers, all a little jealous of Christmas’ fame, and all inclined to belittle one another. They sat about the hotel lobbies, spinning yarns about “that little affair down in Nicaragua,” or “that little scrap up in Honduras,” and if I mentioned to one the story of some other, he would snort loudly with derision.

“Don’t you believe it! He’s a damned wind-bag! Next time he mentions getting that sword stuck through his lung, you just ask him if he remembers the mule that got him up against the corral wall and kicked hell out of him!”

VIII

Guatemala has had its revolutions from time to time, yet its history—as compared with that of its immediate neighbors—has been fairly peaceful.

If it has not had a succession of good rulers, it has at least had a succession of strong rulers. Its Indians are a docile race, a race much more easily conquered by the Spaniards than were the Indians of Mexico, and much more easily dominated by the white landlords of to-day. And the army, if not impressive when on dress parade, is one of the most dependable armies in Central America.

In recruiting its soldiers, the government resorts to the selective draft. The Jefe Politico—the all-powerful local official—visits each coffee planter, and secures a list of the pickers who have picked the least coffee during the past year. These, provided his soldiers can catch them, are enlisted in the army. Once enrolled, the little peons are equipped with uniform, not very elaborately or neatly, but sufficiently to distinguish them from civilians. In the Capital, they are also equipped with shoes, not for efficiency but for the sake of appearances. Unaccustomed to footwear, they have to be trained to its use, and nothing is more amusing than the sight of a new battalion thus shod and stumbling awkwardly over the rough streets. They look uncomfortable and self-conscious, and at each halt will pick up their feet and glare at the shoes much as milady’s poodle glares at a pink ribbon tied around its tail.

Yet these little Indians, stupid and illiterate, make better soldiers than the more intelligent mestizos, or mixed-bloods. They are more susceptible to discipline. In most of these countries, virtue goes with ignorance, to such an extent that the mixed-bloods are called ladinos in Guatemala—a word that originally meant “tricksters.” The little Indians are far more loyal to the president in office than are the mestizo soldiers of the neighboring republics, and are less apt to desert the existing government when an insurrection threatens.

Guatemala’s several Dictators, also, have been artists at the business of discouraging opposition.

Of them all, Estrada Cabrera stands out head and shoulders above other despots not only of Guatemala but of all Latin America. Until a very few years ago he reigned for term after term, proclaiming himself re-elected when necessary, and quietly murdering any politician who gave the slightest indication of opposing him.

Why he clung to the presidency is a mystery. He was so fearful of assassination that he scarcely ever showed himself outside the palace. He slept usually in a house across the street, reached by a secret passageway. He ate nothing except what his own mother prepared for him. He would have a dozen beds made up each night, and only one or two of his most trusted guardians knew which one he occupied. He seriously handicapped the country’s mining interests by placing a ban on the importation of blasting powder, lest it be used to blow him up. On the one occasion when he attended a public ceremony, a bomb killed his carriage-driver and the horses, barely missing the Dictator himself. Since it was exploded by an electrical device, he thereafter placed a ban on all electric contrivances, and visitors to the country were relieved even of such things as pocket flashlights.

But from his isolation within the palace, he manipulated all the strings of government, and all Guatemala felt his power. He personally blue-penciled every foreign news dispatch that left the country, and sometimes even the personal cablegrams. He maintained an elaborate spy system, with one agent watching another agent, until every man in the republic was under survey. He permitted no public gatherings where people might discuss politics. He forbade the organization of any kind of society, and once suppressed a chess club.

Quite possibly, he believed that these measures were justified. It is affirmed by many that Guatemala made more progress under his rule than at any period of brief presidencies. Certainly he did not follow the course of enriching himself sufficiently in one term to spend the rest of his life in Paris—a course extremely popular among Central-American executives. And many an Old-Timer will say, “The old devil was never so bad as they pictured him.”

But those who opposed his will used to die quite silently and suddenly, and his enemies affirm that Cabrera used poison. One hears strange stories about his political methods:

He is said on one occasion to have decreed the death of an American who had incurred his enmity. To avoid international complications he dispatched a second American to do the dirty work. The second American went to the first, warned him, and advised him to leave the country. Then he returned to inform Cabrera that the other man had escaped. He did not know that a native spy, having followed him, had already reported the meeting. Cabrera smiled. “That is too bad! But you could not help it, so have a cocktail with me, and forget all about it.” Three hours later, the American did forget all about it. He dropped dead.

One hesitates to believe all the stories, for Old-Timers love to shock the itinerant journalist. But certain it is that he kept all Guatemala in terror of his authority, until many of the more ignorant believed him gifted with supernatural powers.

In his later days, as in the history of most despots, he lost his grip upon the country. He had made too many enemies. Every one hated him, yet hesitated through fear of spies to be the first to proclaim opposition. But the inevitable revolution finally materialized, and Cabrera fled the capital. He surrendered on condition that his life and property be respected. It is to the credit of the Guatemalans that they observed their agreement, although lynch-law might have been more justifiable.

One Carlos Herrera, a wealthy landlord, took his place, but he did not relish the job as did Cabrera. After a few months, when some one else started a revolution, he made no objection. It was comparatively bloodless. A few policemen were the only casualties. They had not been informed that a revolution was scheduled, and when they saw the mobs surging up the street, undertook to quell what they considered a disorderly scene. One completely organized government went out overnight, and another completely organized government came in. Shooting was by way of celebration. An American who had an engagement with Herrera the next day went to the palace, and inquired, “Is Herrera in?” and received the answer, “Herrera’s out; Orellana’s in.” Only one man was arrested. He landed in Puerto Barrios, the north coast port, with a cheerful jag, and cabled Herrera, “On arriving in your beautiful country, I hasten to salute you and to wish you a long life and a merry one.” The new government arrested him for treason, but released him as soon as he proved his ignorance that a revolution had transpired.

WHEN ORELLANA STARTED A REVOLUTION, PRESIDENT HERRERA MADE NO STRENUOUS OBJECTION

THE ONLY CASUALTIES WERE A FEW POLICEMEN WHO MISTOOK THE REVOLUTION FOR A DISORDERLY DEMONSTRATION

Orellana, who held office at the time of my visit, was a former lieutenant of Cabrera’s. He had occupied the seat beside Cabrera when the bomb blew up coachman and horses. There were rumors afloat that Cabrera’s brain still directed the government, but they received little credence. Another story, purely humorous, was that on the night when Orellana overthrew Herrera, the ex-Dictator started to pile all his furniture against the door of his room.

“But, sir,” protested a servant, “these are your own friends coming back into power.”

“That’s why I’m doing this,” said Cabrera. “I know those fellows!”

Cabrera’s house was a fortress-like structure of unassuming exterior. An old man now, he was still following his life-long policy of retirement from the public gaze, and a guard of soldiers was present to see that he remained in retirement. The family came and went freely, but the ex-Dictator never showed his face. If he had done so, some one might have taken a shot at it. He probably welcomed the guard for its protection.

Orellana, despite his former connection with Cabrera, was proving a more lenient president. Clubs were now thriving, and the people might congregate where they pleased. Poison had been abolished as a function of government. And men might discuss politics without being shot. Few, however, publicly suggested a change of president. With all its comparative liberality, the new régime was ruling with an iron hand characteristic of Guatemalan governments. Shortly before my visit, Orellana had chased home a party of Mexican bolshevik agitators attempting to spread their propaganda among the Indians of his republic. A few years earlier, when his railway employees threatened a strike unless permitted to select their own officials and to discharge all foreigners from the service, the American superintendent had told them to go to Hades, and Orellana had sent them back to work by threatening to draft them all into the army.

These countries always thrive best under a stern dictator. Even under the tyrannical Cabrera, Guatemala enjoyed more prosperity than it would have enjoyed under a rapidly-changing series of get-rich-quick presidents. For a land of illiterate peons, a dictatorship, if exercised with justice, is always the most satisfactory form of government, except to politicians out of office.

IX

The two principal products of Central America are coffee and bananas. The Central-American remains in the cool highlands of the Pacific coast, and raises the coffee. To the invading foreigner he cedes the lowlands of the Caribbean for the culture of the bananas.

In Guatemala, it was a day’s railway journey from coffee country to banana country—first through a stretch of magnificent scenery, of forested mountains, and of rugged gorges spanned by several of the world’s highest railway bridges—then through a tedious expanse of desert, where the woodland gave way to scraggly cactus, and the mountains (although still majestic and piled one atop another until they reached the clouds) were swept by a fitful wind that blew gustily, transferring the sand from the landscape to the eye—and finally down among the swampy, jungle-grown lowlands of the coastal plains, into the empire of the United Fruit Company.

The stucco dwellings of moorish design gradually gave way to wooden shanties, and Guatemalan natives to West Indian blacks. Years ago, before sanitary engineering made the tropics liveable, the inhabitants of this region had retired to the cooler highlands, where snakes and fever were less abundant. To-day the greater part of the East Coast, all the way from Guatemala to Panama, is in the hands of the United Fruit Company or its several minor competitors. Except in Guatemala or Costa Rica, which have rail connection from ocean to ocean, banana-land is closer to New Orleans than to the capital of its own country. It is peopled with a few American or English bosses, and a host of imported negroes. Its prevailing language is English. And it bears more resemblance to Africa than to the Central America of which it is a part.

A young English superintendent met me at Quiriguá, one of the United Fruit Company’s plantations, and conducted me to a cottage with screened verandas, where one might have fancied himself in the Americanized Canal Zone. The camp was neatl