CHAPTER XV

WHERE MARINES MAKE PRESIDENTS

I

To journey from one Central-American republic to another, the traveler should equip himself with a private yacht.

Having neglected this precaution, he must resort to patience. There is a steamship service along the Pacific Coast which advertises regular sailing dates. But since its vessels are quite apt to be ahead of their schedules, one usually repairs to the seaport a day or two in advance. And since they are far more apt to be behind their schedules, one usually waits there for a period varying from one to three weeks, at a shabby hotel in a blazing hot town whose inhabitants earn their living by overcharging such travelers as fate has thus thrown into their grasp.

II

Not possessing the private yacht, I left Tegucigalpa for Amapala one day in advance.

Bill, the hard-boiled, took me down the mountain road to San Lorenzo, where a launch was already waiting. There a member of the crew undertook to facilitate my voyage. He greeted me with a smile as I reached the end of the wharf.

“I’m the man who carried your suit-case, señor.”

“I carried it myself.”

“Did you really? Then I’ll put it on board for you.”

Since a squad of Honduran soldiers held all passengers on the wharf until the baggage was aboard, I surrendered it to him, and he placed it on the extreme edge of the stern, precariously balanced on the small end, tying it fast with the rest of the cargo, but with a flimsy piece of cord which threatened at any moment to break and spill the entire load into the Gulf of Fonseca.

“It’s all right,” he assured me. “I have my eye on it!”

Then, as the soldiers finally permitted us to embark—after an official had ascertained that my passport was properly viséd by the Honduran Minister of Foreign Relations—the officious mozo climbed upon the thwarts to offer me an unnecessary hand. “When we arrived at Amapala, señor, I’ll show you to the hotel.”

“I already know one hotel there.”

“Then I’ll show you to the other one.”

I had frequently encountered his type in nearly every port of the world. He believed all traveling Yankees to be simpletons with the one redeeming virtue of lavishness in bestowing tips for useless services. Throughout the four-hour ride across the Gulf, he sat opposite me, smiling sweetly whenever he could catch my attention. And when we drew up beside the wharf at Amapala, he untied my suit-case first. But having untied it, he left it while he assisted the rest of the crew in dragging eight heavy trunks up a slippery flight of wooden steps.

According to local custom, another squad of soldiers herded all passengers ashore to answer another questionnaire, and from the dock I looked down to see my suit-case dancing and rocking unsteadily with each swell that rolled in from the misnamed Pacific. From the opposite end of the launch, the mozo held up his palm in the Latin-American gesture that signifies, “Patience.”

“No hay cuidado, señor. I’m watching it.”

But it was already toppling. And the shadowy figure of a shark, cruising about the murky waters below, suggested the impracticability of recovering it later by diving. Avoiding the guard, I landed back on the launch, and caught the suit-case just as it started to fall. Four ragged urchins, waiting on the dock to carry baggage, leaped after me to struggle for its possession. The mozo joined the fray. We surged back and forth across the deck, while the shark waited below, until our battle was interrupted by a policeman with drawn revolver.

“You are arrested!” he screamed at me.

And he marched me to the commandancia, where a pompous official lectured me, politely but firmly, upon the insult I had paid the government of Honduras. It was a small country, he said, but it possessed high ideals. The authority of its army was a thing to be respected. Considering that I was a foreigner and not acquainted with local customs, I would be forgiven. But in the future, he hoped I should never jump off a dock onto a boat until all cargo was unloaded.

As I walked out of the office, still clinging to my suit-case, the mozo came up to demand his tip for keeping an eye on it. I waited a moment to see how much the policeman would expect for his services in arresting me, but he collected only the customary fee which all passengers paid for the use of the wharf in disembarking.

So I turned toward the steamship office, to learn when I might proceed to Nicaragua.

“Quién sabe? We expected two passenger vessels. But the one, last night at La Unión, went back to La Libertad for six more sacks of coffee. And the other, having filled with coffee at San José de Guatemala, has canceled its schedule entirely.”

III

I stopped at the leading hotel, operated—like most hotels on this coast—by a Chinaman.

It was the usual type of seaport hostelry, less comfortable and more expensive than those of the interior cities, but well stocked with fleas, bugs, liquor, and flirtatious servant maids.

“What does one do in this town for amusement?” I asked a native.

“Amusement?” He seemed a little surprised. “Why, señor, there are plenty of women.”

For occupation, the male population carried the baggage of passing travelers. The female population took in washing. Rather dark, and not distinguished for beauty, the younger ones called at the hotel for the laundry; the older ones did the work. They took the clothes to the waterfront, laid the garments on flat rocks, and pounded the buttons off with a stout club. Then they left them to bleach, spreading them out on scrubby little bushes whose berries stained them with yellow spots, while they themselves—already stripped to the waist for comfort—retired to the shallow water to immerse themselves through the hot mid-day. In the evening they collected the garments, carried them home, and ripped them into shreds with rusty irons. Finally, having wrapped them into a neat bundle with the least-ruined articles on top, the younger girls brought them back with smiling countenances, and the inquiry:

“Is that all, señor?”

As a town, Amapala was not unpicturesque. Its whitewashed houses, beneath red-tiled roofs, were set amid palms and bougainvillea. If at noon it seemed to wither under the dry white heat of a tropic sun, there was usually a breeze in the evening, with a tang of salt from the ocean. Across the Gulf of Fonseca, if one looked beyond the fleet of scows and lighters in the foreground, one could see myriad islands and the cones of several Salvadorean volcanoes. There was a play of red and gold at sunset, then the purple and silver of twilight, and finally a glorious night with stars twinkling above and fireflies below, and the glare of the volcanoes tracing a crimson path through the waters of the bay.

Its only point of interest, however, was the cliff where occurred a bloody incident in a long-past war between Nicaragua and Honduras. Some many years ago Nicaragua, having confiscated a smuggling schooner, had armed it with a cannon, and feeling rather cocky in its possession of a navy, had dispatched it to fight Honduras. It came up to Amapala and fired one shot. The bloody incident occurred when a Honduranean, standing on the cliff, craned his neck to see where the shot landed, and fell into the Gulf of Fonseca.

From the cone of the extinct volcano that rose above Amapala, one could see Honduras, Salvador, and Nicaragua. Each was but a few hours’ distance from the other, yet the traveler might wait indefinitely for a boat. Shields, my companion on the auto trip from Guatemala to Santa Ana, was now in Amapala, also bound for Nicaragua, and had already been waiting over a week.

He spent most of his time on the hotel veranda, scanning the horizon with a telescope. This operation afforded much entertainment for the village idiot. Each Central-American port seems to contain one weak-minded or defective youth, who sits all day at the hotel to watch the every movement of a visiting foreigner. In Amapala it was “The Dummy.”

He was a harmless, pleasant little brown fellow in ragged breeches and an undershirt salvaged from the rubbish pile. How he lived, no one seemed able to explain. Some one apparently fed him. No one apparently washed him. Occasionally he earned a few pennies by performing tricks for tourists. His chief accomplishment was that of resting his bare toe upon a lighted cigarette. He was always cheerful, and affable, and he would chat with us by the hour in parrot-like squawks made intelligible by a marvelous art of mimicry. He could describe any one in Amapala by a single gesture. For the Commandante he twisted an imaginary mustache. For the Chinaman, he pulled down his cheeks to give his eyes an oblique slant. He became our constant associate and entertainer, guide, counselor and friend.

From time to time, as an alternative amusement, Shields wrote passionate love letters to the daughters of the Commandante—the only two white girls in town—to which missives, I later learned, he usually signed my name. The Dummy would serve as emissary, and upon his return would enact the giggling of the señoritas, and the wrathful explosions of their parents.

Toward evening, the two girls sometimes made their appearance to stroll in the plaza, accompanied by a male relative with a rifle. Occasionally they would stop at the hotel for a glass of lemonade, and would subject Shields and myself to the careful scrutiny to which señoritas invariably subject a strange youth, while their companion sat beside them with the rifle over his knees. Still later the Commandante himself would join them, favoring us with a stern military glance of warning.

The Dummy always sidled away at his approach, for the Commandante had arrested him not long ago. He often told us the story in his own crude language. The trouble had been about a woman. From his ecstatic expression, she must have been beautiful. He would point at his face, then at his black trousers, to suggest her complexion, and a twist of his fingers would indicate kinky hair. He showed us in pantomime the evil intentions of a rival. He seized a rock and planted it with much zest against the villain’s imaginary skull. He whistled shrilly. That was a policeman! He slumped into a heap as the imaginary club descended upon his head. He placed his wrists together. Handcuffed! He held up ten fingers. The Commandante had sentenced him to ten days! Then he gave a series of unintelligible parrot-squawks, and pointed toward La Unión. During his imprisonment, the girl had fled with the rival! He shook his head sadly, and ran a hand across his throat. Was he meditating suicide? Or was he planning revenge? His story always ended in the harsh, mirthless laughter of an imbecile, and he sidled away, for the Commandante, having partaken of his cocktail, was leading his family home.

In the evening the Consular Agent, fat and jovial, would drop in for a glass of beer. His only official duty at present was looking after a Panamanian sailor who had fallen down the hold of the last vessel in port and broken a shoulder bone.

“It might have killed a white man, but you can’t hurt these natives. Down in Nicaragua, I saw one fellow sink a pen-knife two inches into another fellow’s skull. We just pulled it out, and the man went on working.”

And many other yarns would follow, the locale varying from Chile, where they use those little curved blades with an upward thrust, to the Philippines, where the Moros take your head off with one deft swing of a bolo. We would all collaborate, the stories growing more and more astounding until we reached the incident of the Mexican who swam two miles after a shark had bitten off his stomach.

“I believe it,” the Consular Agent would nod. “Down in Costa Rica a shark bit one of my pearl-divers, and took out a chunk as big as a watermelon. We clapped it back on, plastered the edges with a little mud—”

Then we would have another beer, and the Consular Agent would stroll homeward. The street lamps flickered. Five ragged soldiers—the night patrol—glided past us like phantoms through the dark street. A peon girl hurried along the sidewalk, and the Dummy, bidding us good-night, ran after her with shrill parrot-like squawks. Within the hotel the Chinaman sat imperturbable as a Buddha, waiting to close up his establishment, while the town’s three German merchants drowsed at a table.

Shields and I would rise and yawn.

“To-morrow there may be a boat.”

IV

The one break in the day’s monotony came at mid-afternoon.

Then a shore-party from the Rochester, still lingering far out in the harbor, would shoot past the waterfront in a trim white launch, and come rolling up the long wharf to see the sights of town.

Whenever the Chinaman saw them coming, he would shout for all his servants to man the bar.

The sailors, seeming to know the local geography instinctively, headed straight for the hotel. While their Ship’s Police scattered out through town with swinging clubs, the tars all trooped into the establishment.

“Hello there, buddy! Say, kin you talk this spig language? Tell that Chink we want liquor!”

And presently they were all over the city, bargaining in every shop, contriving somehow despite their ignorance of Spanish to obtain whatever they desired. They purchased native rope bags, and filled them with fresh eggs, live turtles, earthenware jars, Spanish daggers, goat-skulls, fruits, vegetables, and snake skins. They stood on street corners, frowning over handfuls of unfamiliar coins received in exchange, wondering to what extent they had been cheated.

“Hey there, feller. You’re a Yank, ain’t you? Tell me how much I’ve got here in real money.”

One husky tar, with a sailor’s knack of getting acquainted, rolled up the street with a native girl on his arm, amid the cheers of his friends. He had a sandwich in one hand, and a flask in the other. She was a chubby little brown creature, in a tight-fitting red dress, and her short fat legs bulged above the tops of high, tightly-laced boots that appeared newly purchased.

“Wait a minute, sister. We’re goin’ in here an’ get you a hat. You’ll be some swell skoit when I get finished wit’ you.”

They vanished into a shop. When they emerged, the lady wore a green and yellow bonnet trimmed with purple and blue. She was leading her hero toward the village photographer’s to immortalize in tin-type this thrilling event. They came out with the photographer’s parrot. The sailor had purchased it, and was teaching it to say:

“To hell wit’ the marines!”

Gradually, as the hour of departure drew near, all would gravitate toward the saloon at the wharf, where they purchased more flasks of whiskey for the journey to their ship. The little native bartender, overwhelmed at the many orders shouted at him in a strange tongue, became completely paralyzed, whereupon every one helped himself, and tossed greenbacks across the bar. At last the S.P.’s commenced to herd the crowd toward their launch. A delinquent always came running from town at the last moment, his bag of eggs bouncing against his uniform and creating golden havoc. The little native bartender came to life to scream that two flasks had not been paid for. The escort of the lady in the red dress had a fight at the end of the wharf with several of his cronies who considered it their privilege to kiss her farewell.

“Act like gentlemen, you —— —— ——, or I’ll poke you one in the snout!”

Then, packed into their trim white craft, they were gone, leaving Amapala flooded with crisp new American greenbacks.

V

Our steamer finally came.

After our two weeks of waiting, it picked us up and landed us within eight hours at the Nicaraguan port of Corinto.

For years Nicaragua had been the especial protégé of the United States government, financed by American bankers, and policed by American marines. Having traveled for several months in republics not blessed with such attentions, a gringo naturally looked forward to the progressiveness and modernity of Nicaragua.

No difference was evident.

We landed at a fairly good dock, and sat there for three hours while the American-supervised customs officials finished their siesta. Then we passed into such a town as might have formed the locale of O. Henry’s “Cabbages and Kings.”

The unpaved streets were grown with grass, neatly cropped by grazing herds of livestock. The buildings were mostly flimsy wooden structures sadly in need of paint. There was nothing to distinguish Corinto—the principal seaport of Nicaragua—from any other port along the Central-American coast.

A railway—one of the American-managed institutions—carried me inland through a scraggly jungle. The country was comparatively level; occasional volcanic peaks, rising abruptly from the plain, had rendered it fertile with their lava dust; frequent lakes indicated a plentiful water supply. Yet one observed few of the rich plantations that covered such land in the other Central-American republics; occasionally there was a field of pineapples or sugar-cane; as a rule, the road led through wilderness.

León, the second city of Nicaragua, lay thick in dust. Its streets were unpaved. Its houses, of brilliant green or yellow, with trimmings of blue and red, were resplendent in the blinding tropic sunlight, but upon close inspection, they proved somewhat dilapidated. Its cathedral towers, rising at every corner, were cracked and ridden from earthquake and revolution. The whole town seemed very old and very sleepy, and drowsing in the memories of a past. The American occupation had brought an end to civil strife on a large scale, but it evidently had not brought the prosperity to mend its ravages.

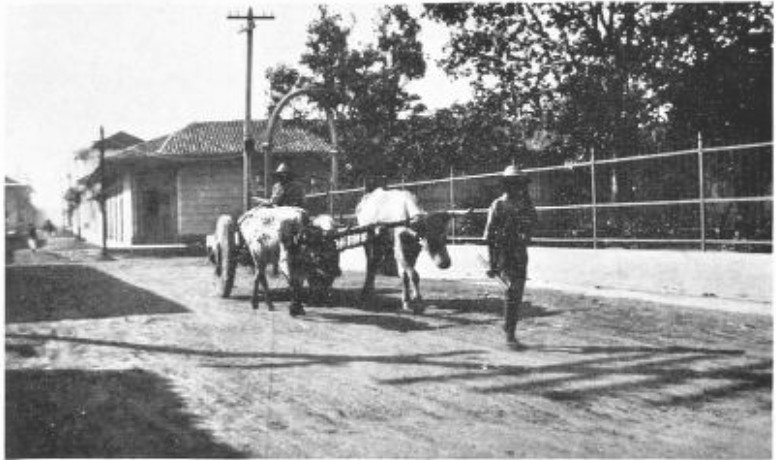

THE AMERICAN INTERVENTION HAD BROUGHT PEACE, BUT MANAGUA’S DUSTY STREETS SUGGESTED NO PROSPERITY

Managua, the capital, was in no better repair. It was situated at an altitude of only 140 feet—by far the lowest altitude of any Central-American capital. It sweltered in heat, relieved somewhat by the breezes from its lakefront, but like Corinto and León it was a city of sand, and the breezes filled the streets with swirling dust. Each lumbering ox-cart left a cloud in its wake. It lay two inches deep on the main avenues. It covered the grassless plaza, and the barren expanse of desert before the old cathedral, where vegetation was sprouting from a fallen spire. It settled upon the low roofs of the drab shops and dwellings. It seeped inside through door or window, and formed a coating upon the tiled floor of the hotel. Now and then a civic employee would turn a hose upon some portion of the Sahara, to convert it momentarily to mud, but no sooner did he cease than the blazing sun reconverted it to sand, and the breezes sent it whirling again.

Nicaragua was a country of many natural advantages. Its people appeared to be of better caliber than those of Honduras. Its area—49,200 square miles—was the greatest in Central America. Its land was all suitable for cultivation. Its potential wealth—in mahogany and hardwoods, in gold and silver and other metals—is estimated by many authorities to exceed that of any of its neighbors. Yet the imports and exports of this largest republic were far below those of Salvador, the smallest. Its cities—although upon closer inspection, they proved to contain better shops and hotels—were outwardly less imposing than those of Honduras. And when I offered a merchant a ten-dollar bill, he threw up his hands with the exclamation:

“You must change your large money at the bank!”

I turned to an Old-Timer, himself an American.

“Hasn’t our country done anything to make this a regular republic?”

“Son,” he said, “this was a regular republic before our country stepped in.”

VI

The story of the American coöperation—which the Nicaraguans themselves describe by a less pleasant word—dates back to 1909.

At that time Nicaragua had a Dictator. José Santos Zelaya had been reëlecting himself president for seventeen years. He had commenced his reign, stern though it was, with fairness and justice toward his countrymen and friendliness toward foreigners. In his later years, overwhelmed with conceit at his success, he came to regard his Dictatorship as a right that carried with it the privilege to amuse himself as he saw fit. If he needed money, he horsewhipped the wealthier merchants until they offered a “voluntary” contribution. If he saw a woman he desired, he sent for her to come to the palace. Presently he commenced to meddle in his neighbor’s affairs, fomenting revolutions in the adjoining countries, and thumbing his nose at the United States.

In 1909 a revolution started in his own country, over at the isolated port of Bluefields on the Caribbean coast. There are rumors that it had the backing of American capitalists. These rumors arise from the fact that Adolfo Diaz, then the treasurer of the revolution—and later the leading actor in the drama—was an humble employee of an American concern. Diaz denies these rumors. “Every penny,” he told me in Managua, “was contributed by Nicaraguans.” But certain it is that the revolution had the sympathy of the United States government.

President Taft, at the time, frankly described Zelaya in a message to Congress as “an international nuisance.” And when, during the fighting, the Zelayistas executed two American soldiers of fortune caught red-handed attempting to dynamite troopships on the San Juan River, the American government made this trivial incident the pretext for hinting broadly that it was time for Zelaya to resign. Zelaya did resign, leaving the presidency in the hands of an excellent man backed by all the old lieutenants of the Zelayista party. The United States was not satisfied. And when the Zelayistas, having licked the revolutionists to a frazzle, were about to take their stronghold at Bluefields, an American gunboat intervened on the ground that further fighting might destroy American property.

From some mysterious source—which all Latin America believes to be the United States—the revolutionists obtained new ammunition. They sallied out from Bluefields again, thrashed the Zelayistas, and overturned the government. One General Estrada, the leader of the insurrection, became president, but he soon gave way to Adolfo Diaz. Now enters upon the scene the American banker.

President Diaz found the country bankrupt. There is much controversy as to how the debt originated, each party blaming it on the other. The truth is that Zelaya had left several millions in the treasury because he had just negotiated a loan with British bankers and had not had time to spend it. He also left a long list of claims because of his high-handed confiscation of property. The revolutionists had doubled the bill by their own destruction of property during the warfare. Wherefore blame is divided. The important fact is that Don Adolfo found his country in debt to the extent of over thirty-two million dollars, a staggering sum to a small republic. He called upon a firm of New York bankers for a loan of fifteen million.

This transaction was arranged through the American State Department by a treaty which the Senate—newly turned democratic when Wilson replaced Taft—refused to ratify. Nicaragua, however, regarded it as an agreement. As security for the loan, the bankers took over the collection of the customs, and arranged to look after the whole business of the national debt. They never advanced the loan. They did advance a million and a half, followed by comparatively trifling sums, to stabilize the currency and reorganize the national bank, but they also took over the bank. Later, when another million was advanced, they took over the operation of the Nicaraguan railway.

President Diaz, now retired to civil life, assumes full responsibility for these transactions. He is a pleasant little gentleman with graying hair and a frank, boyish smile.

“I asked the bankers to do it. I was taking the only means I had to bring my country out of financial chaos. But I became, as a result, the most hated man in Nicaragua.”

In fact, all Nicaragua called him a traitor, accused him of selling the republic to the American capitalists, and rose to overthrow him. For three days, in 1912, the rest of the country poured cannon balls into Managua, until President Diaz asked the United States for protection. Two thousand American marines were promptly landed. Having suppressed the revolution, they left a “legation guard” in Managua as an intimation that the United States stood ready to suppress any further uprisings.

Indirectly these marines make presidents to-day.

Elections in Nicaragua are as much a farce as in Mexico. Whoever controls the polls wins the verdict. Wherefore the Conservative party, which first invited the American bankers, has remained steadily in power. It can be defeated only by revolution, which the marines prevent.

“You ought to be here at election time,” said an old American resident, “and see them run their voters from one booth to another by the truckload. They number about one-tenth of the population, but they always win.”

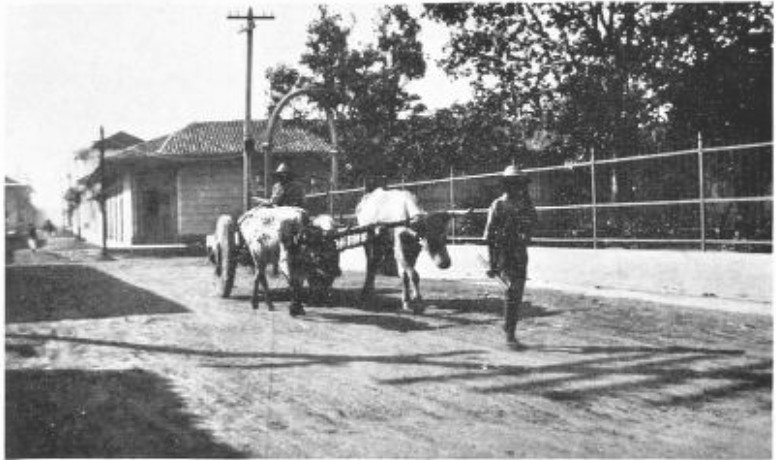

If the marines were withdrawn—even the Conservatives themselves admitted to me—the present government would be overthrown within twenty-four hours. Nicaragua, as a whole, never endorsed the invitation to the American capitalists. When the Conservatives invited them, the entire country turned Liberal. If Zelaya were to come to life and return to Managua, he would find the republic waiting with open arms. But while the marines are present, the Liberals are helpless.

IF THE AMERICAN MARINES WERE WITHDRAWN FROM NICARAGUA A REVOLUTION WOULD TRANSPIRE OVER-NIGHT

At the time of my visit another election campaign was starting. Realizing their dependence upon Washington, the Liberals had affected a change of heart, announcing that they would support the bankers as ardently as the Conservatives, and asking for a new election law which would keep their opponents from stuffing the ballot boxes. A new law had been drafted by a New York lawyer. The Liberals were hopeful, but uncertain.

“Who will be your candidate?” I asked one of their leaders.

“We do not know yet,” he said. “We have not heard who will be most acceptable to Washington.”

During my several weeks in Managua, I talked with most of the actors who had played leading rôles in the international drama. I do not believe that the United States was guilty of a deep-laid plot to gain possession of the little republic. I believe that the American government acted for the best interests of the Nicaraguans. But when one reviews the train of events since 1909, one sees at a glance that they can very easily be misinterpreted until they look decidedly nasty. First came a revolution, assisted by an American gunboat, which doubled the already-overwhelming national debt. Then came American bankers, taking charge of the national debt, and exacting as security everything of value in the republic. Then came the American marines, keeping in power the minority party that invited the bankers, against the will of Nicaragua itself. And all Latin America chooses to regard these events as part of a deep-laid program of intrigue.

VII

There are always two sides to a question.

Nicaragua, under American supervision, has made progress, but it is a progress which, both to the permanent resident and the casual tourist, is altogether invisible.

Outwardly, since the coming of the bankers, the republic has marked time. No large industries have been introduced. No railways have been built. The greater part of the country is without means of communication or development. The cities are in worse repair than those of Honduras. And, although the bankers deny it, every Nicaraguan—and nearly every foreign resident—proclaims that the country is far less prosperous to-day than in the worst days of Zelaya.

This is largely due to the fact that the bankers administering Nicaragua’s finances are devoting all their attention to clearing up the old national debt.

Colonel Clifford D. Ham, the American collector of customs, has reduced this debt from over thirty-two million dollars to less than nine million. There is no country in the world, except the United States, whose finances are to-day in such flourishing condition as those of Nicaragua. But this means nothing to the average native. No Latin-American is ever roused individually to a high pitch of enthusiasm over the prospect of paying what he owes. Collectively he finds the idea quite objectionable, particularly when the indebtedness was contracted a long time ago. And so he says, “These Americans turn aside at our very gates every penny that would otherwise flow into the country; they are draining the very life-blood from the nation!” He points to the fact that when the American government, a few years ago, purchased the rights to build a Nicaraguan Canal at some time in the future, and paid therefor three million dollars, the money never left New York, but was applied immediately upon that infernal debt.

The national bank has stabilized the currency, so that the Nicaraguan cordoba is on a par with the American dollar. According to the bankers there is more money in circulation to-day in Nicaragua than ever before. But the Nicaraguan insists that prices have risen so that