Chapter 11 Hargrave

argrave shows little resemblance to its counterpart Hartest, few landmarks remain. The church of course dates back to Norman times, Rogers lane was a simple track cart then. The tenements and Large house have gone.

argrave shows little resemblance to its counterpart Hartest, few landmarks remain. The church of course dates back to Norman times, Rogers lane was a simple track cart then. The tenements and Large house have gone.

In pre-Reformation days, Hargrave was a small village 6 miles south-west of Bury-Saint-Edmunds. In 1550 AD, it centred on a village common, boasting a Manor house, an inn - (at which the main stagecoach routes from Colchester to Cambridge and London to Norwich would cross), a church, a school and the remains of a wooden Saxon castle.

Hargrave means Hares grove, (though it may have meant to be a deviant of Grey grove). William the Conqueror gave the village to the monks and monastery of Bury-Saint-Edmunds in days when it was known as Haragrave. Pope Eugenius IV in turn gave it to Abbot Anselm in 1147. One quotation of the day from an unknown source of the day described Hargrave as :

‘Hargrave is rather a depressing village and

apt to bring to one’s mind the well known lines:--

“out of the world’s way,

out of the light, forgotten of men altogether” 152

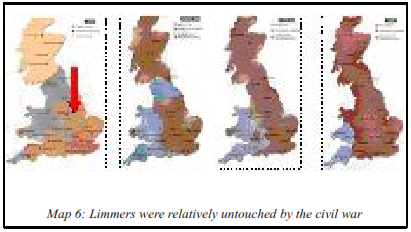

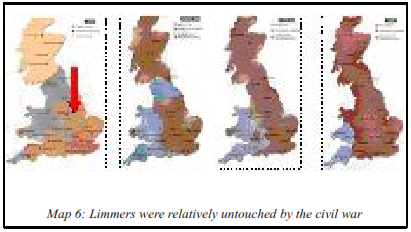

Perhaps that was to Limmer’s advantage in an era of Civil war. It was a good place to 'keep one's head down'. Hargravians, who had been strongly influenced by the Parliamentarians, were also able to persuade royalists not to interfere. After all the country needed its grain whoever won the civil war. Limmers seem to have remained undisturbed in this sleepy village while battles between Cavaliers and Roundheads raged up and down the land. Somehow, it did not come near them as we can see from the strip map The arrow points to where Limmers lived and the brown shows the progression of the war.

Records show153 at this time, besides the Abbots land, there were four carucates154 of land divided among six villains, who had four slaves, two plough-teams, two beasts, five hogs, and common access to four acre of meadow and woodland for sixteen hogs.155

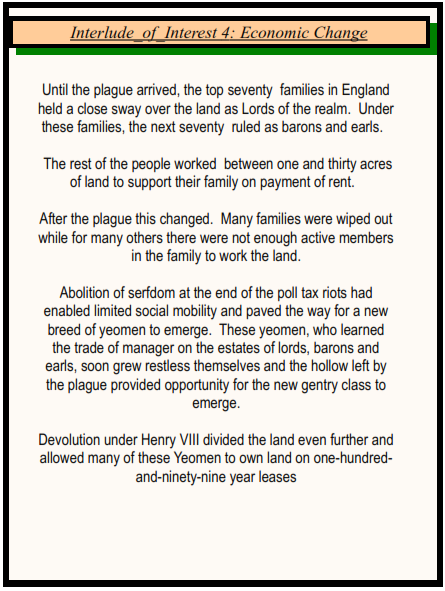

Unfortunately, Family records are sparse156 at the beginning of the Hargrave era so we start our adventure with detective work. By working backwards from the known to the unknown, as we do, it becomes clearer that there were at least two nuclear families of Lymmers farming in Hargrave before devolution.

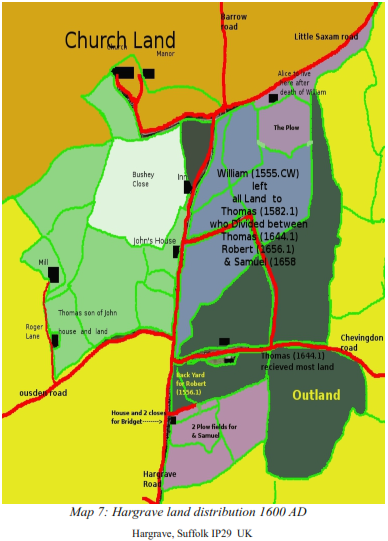

We begin our story of Hargrave with the Abbot who became Chief Lord of the Manor in 1286. The Manor lands were in a boundary of 140 acres. Four houses, in four plots of land of around one hundred and fifty acres stood on the southern side. Two of these were sub divided and later a block of tenements were added on the opposite side of the main road to the inn and stagecoach stop. To the north east was common land and woods157 on which stood the village water supply – the well.

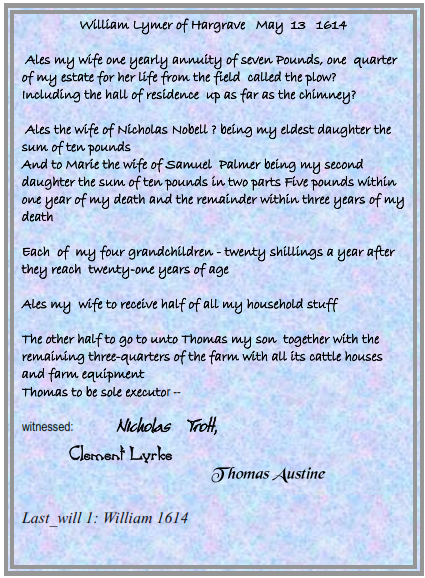

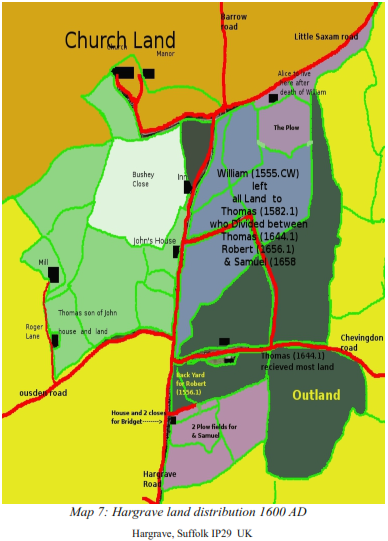

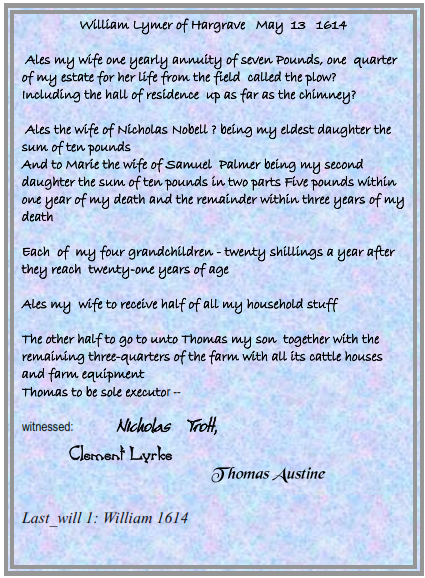

To the north-west of the village stood the farm and house most likely to have housed the first Lymmer family. This farm's northern border ran alongside the church estate, which, at the time, was run by the abbot and his monks. Roger Lane ran from the main Ousden road (known then as Howesdon), to a Mill house built sometime after 1520 AD. What we cannot tell is if Roger was born in Hargrave or even if he owned this land, Roger may have had land in Hartest, but that is also unclear. I say that this is the likely home of Lymmer because we know that there are at least two brothers living in Hargrave, John, perhaps born a little later than 1545. We will call him John(1545.28). He seems to have remained in this house and farmed the land, while William, born some time before 1555, William(1555.28), who later worked the farm with the limekiln and the large house to the south-east side of village, which was a piece of land originally given to Robert Payne by King Richard, in 1302 AD. The limekiln, which may have been there then, was handy for William as it was the fad of the day for many farmers to break up heavy clay with lime as they ploughed, quite a lucrative aside for a corn-monger - selling lime alongside seed.

I say it was a large house, it was not as large as others in the village, judging by the hearth tax levied on the house. After William(1584.23) inherited the house from his father he paid 9d on this tax whereas the manor house paid £1: 3s: 0d. The average was about 3d. 158. Just opposite the junction leading to the house was the inn and stables at which stagecoaches stopped.

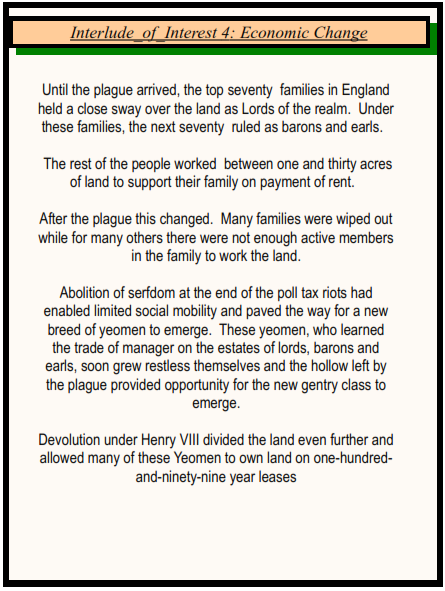

When Henry VIII argued with the Pope, Henry seized the abbey from the Roman Catholic Church and put it under the authority of Sir Thomas Kitson159. He passed the act of disillusionment in 1538/9 AD, fearing that the Pope should still receive monies from the church.

At the time of disillusionment160, Sir Thomas Kitson, Corn merchant and High Sheriff of London161, owned and successfully ran a number of estates by devolving them among sub tenants. Receiving the Manor and all its lands from the king, he honoured the legal and perpetual agreements162 already held with Lymmers163, while devolving the remaining hundred-and-forty acres retained by the abbey, into short term contracts with six Villeins164. At least one and probably two of those Villeins were Lymmers. Several generations later, we find Limmers still working land. We can deduce this mainly from the wills of Limmer families living in Hargrave at this period165. By the second and third generation of these families, there are about seven nuclear families of Limmer farming in the area. From one source we can find the following potted history:

Besides Yeoman and Villeins, there are also recorded one tailor, one wheelwright, one Cordwainer166, labourers, an innkeeper167 and five domestic servants, around fourteen dwellings housed the residents in 1539 but this rose to twenty- one by early sixteen hundred. There is some evidence for assuming the monks not only used the land for agriculture but also introduced building works to repair the Abbey. Horringer seems to have supplied the lime, Chevington the tiles and Hargrave the bricks and pipes 168.

The Chimney and Fire mentioned in William(1555.28) 169 Limmer’s Will may well have been one of the kilns where the firing of clay took place.170 Devolution period ends C1700 AD, when the land was consolidated once again, under the Earl of Bristol.

At a time when industry also increases in Hargrave, (brick makers, bricklayers, blacksmiths), Limmers seem to move out. Possibly seeing the end of their contract looming, they invested in lands around Barrow, Groton Hepworth and many other places. The original small farm at the south of Hargrave seems to stay in Lymmer hands for a few more years after the reconstitution of the Hargrave estate fuelling the understanding that Limmers had had a foothold in Hargrave before devolution.

Hargrave era spanned three Monarchs, Henry VII, Henry VIII and Elizabeth times. Britain is firmly under one monarch and a parliament is established in Westminster. Following the Reformation in England, Queen Mary tried to return the church to Rome but parliament had not allowed it. Elizabeth I had Mary executed and ruled church and state as an iron maiden, then James I of England (James VI of Scotland), deviously promised the Puritans a presbytery system, (similar to the Scottish church council), in return for their support. Instead, having gained what he wanted, he tightened his grip on the church declaring his desire to have absolute control over it. Confronting puritans with the choice ‘ Conform, get out of England or worse’, he began the transportation of 3000 puritans from Suffolk to New England.

How did this affect the Limmers of Hargrave? Were they Royalists, Puritans or abstainers? They certainly kept the company of Puritans and expressed the language of Puritans in their wills. A founder Puritan - Richard Sibbes was Elizabeth Sibbes’ great great-uncle; (Elizabeth married John(1672.39) Limmer)171.

Hargrave may have been a boring place before, but it was growing now, from five households during the fourteen-fifties, rising to twenty-one houses in fifteen-hundred, and then to thirty-two houses by sixteen-seventy-four. Things were now livening up.

Ann(1573.23) Lymmer, would have watched the first nonconformist church grow in the village; meeting at first in ‘ an unknown place’ under three ruling ‘Elders’ with ‘ baptisms being conducted' Sunday by Sunday' 172. Such an event would have made the village a lively place for a while, as organised bands of opposition were well known to follow these new denominations around England and harass them.

Thomas(1582.36) and Susan Lymmer and brother William Lymmer, could hardly have avoided the scandal of Rector Richard Hard who, as a result of an enquiry into ‘Scandalous Ministers173 was ' escorted from the village by troopers' .

John(1566.U) was the teenage lad who caused a little scandal one dark Wednesday evening-being the fourth in lent. He took himself along the road to the next village and entering the close of Oliver Sparrowe of Howesdon and 'borrowed' a gelding from the stables. Finding himself in front of chief justice sir Robert Catlin he was pardoned on the benevolence of Oliver Sparrowe. It seems rather a sledge hammer to break a nut as the prosecuting council was sir Christopher Heydon, had a reputation for his tough stand against crime at the time. The judge also had transported several for misdemeanour’s like this.174

argrave shows little resemblance to its counterpart Hartest, few landmarks remain. The church of course dates back to Norman times, Rogers lane was a simple track cart then. The tenements and Large house have gone.

argrave shows little resemblance to its counterpart Hartest, few landmarks remain. The church of course dates back to Norman times, Rogers lane was a simple track cart then. The tenements and Large house have gone.