THE MERRYWAY ATTACK

The events that follow are necessarily somewhat confused, both from their own nature and from the fact that I was not able to set them down until some ten days after they occurred. They fell out somewhat as follows:—

The Merryway had once been a decent road, but after the fighting in June there was little left but a shattered track running at right angles to the main lines of trenches. The Huns had pushed out a very considerable salient on both sides of this track, and as their ground was rather higher than ours they were able to make life very unpleasant for every one around them.

With the threat of more German attacks still hanging over us and the men quite worn out, the Staff decided that we must keep up our morale by trying to lower that of the Huns. An attack on the Merryway Salient was decided upon as the best way of doing this.

Accordingly one Infantry Brigade and one Field Coy. R.E. went over on the night of August 8th, and under cover of a terrific bombardment surprised the Germans and gained practically all their objectives. All was quiet for two days, the Field Coy. put up quantities of barbed wire and the Staff went to sleep to dream of medals.

The morning of the 11th was cold and misty, and to our great consternation the Huns delivered a very heavy counter-attack. This was quite successful, and we were all driven back with the exception of one post which held out on the Merryway. Here about 30 Huns got held up against our wire and all surrendered, although most of the men wanted to shoot, because we were too weak to find an escort. However we sent them back with two men, but seeing that our flanks were gone and how weak the escort was, they strangled the two men and joined the fight. Everything was now completely mixed up, the gray-coated figures were all around, and odd groups of men were fighting detached battles for their own skins against heavy odds. Our telephone wire was cut, and rockets were useless because of the mist; the casualties were heavy, and it looked as if the line would go. Then I saw Bradley, a fearsome sight, with a piece of his scalp hanging over his ear and his face covered with blood, trying to collect some men. I joined him, and we got a few together and went forward again. In technical language I suppose we led a charge or counter-attack, but it never struck me in that way at all, and I’m sure we had no clear idea what we intended to do.

Bradley was mad, and we went at the first group of Huns we saw. There was a tussle, we killed two and the rest surrendered. Bradley collared one of these himself, a poor miserable kid not more than twenty, and I remember the sight of him put heart into us all.

In all we got forward about two hundred yards and got in touch with the Merryway post, although, of course, we were still a long way behind our original line.

This restored the line a little, and instead of pushing through the gaps on either side of us the Huns hesitated a little and finally dug in about 50 yards away. All the infantry officers were killed and every one was out of touch, so that the Huns were not followed up. During the day reliefs came up, and at night Brigade reported that we held a line of posts in touch with one another about half-way between our first and second positions.

I went up with a few men and some material to try to consolidate the position, but when I got to Merryway post everything was in absolute chaos and there was only a sergeant and six men in the post and absolutely at their last gasp. Apparently they had been attacked again during the day, and had only just kept off the Huns after suffering heavy casualties from trench mortars. It was obvious the Huns thought a lot of this post, and I felt sure they would try to take us during the night. I put all my men on and tried to strengthen the place with sandbags, and made it a little deeper by lifting some bodies out of the bottom. I had 19 men with 150 rounds each and 1 Lewis gun with several thousand rounds—this I placed at the end of the trench to fire up the track.

About 11.30 we were shelled heavily without sustaining casualties, and immediately afterwards a crowd of infantry—about 100 I think—made a dash at us, chiefly down the old track. The Lewis gun opened at once, and I was terrified to find that the Huns had a gun on our flank which was shooting straight at our gun and right into the trench. The gunner was killed at once and Cox wounded, so that the gun was silent. Then the infantry sergeant took it and was shot dead immediately. I shouted to the men to keep shooting at the infantry in front and I took the Lewis gun myself and turned it round at the German gun. I waited for him to shoot, and then fired at the flash and silenced him. I noticed that the men’s firing had died down, and on looking to the front I was relieved to see that the first attack was beaten off—we must have killed a lot, as they were right against the skyline—and there were a lot of them moaning about in front. I felt certain we could hold them if we could keep their gun quiet, so for the next twenty minutes we worked like fiends to raise some protection across the open end of the trench. Then they came again in a sudden rush, but I must have damaged their gun, and without that to help them we could turn our gun right into them and easily held them off. A small party sneaked close up to us on the left away from the gun and threw some bombs right into us, blowing an infantryman to bits and wounding a sapper. Then they shelled us steadily for half an hour and got one of the look-out men in the shoulder—another rifle useless. At this point we had our one piece of luck—found a rum jar with just enough in it to give each man a mouthful—it put new heart into us and helped us more than twenty reinforcements. Everything went quiet for a time, and in thinking things over I had an awful job to keep myself under control. The men were wonderful, but there were only 13 of us left and fully 200 Huns all round. During the lull Cox died in my arms—he was very game, but just before the end he sobbed like a child: “My wife and kiddie, oh God! sir, what’s going to happen to them?—poor kid, poor kid.” And so he died.

Shortly afterwards they came at us again, and thank God none of us realised how many there were. On the right where the gun was we held them off again, but we were hopelessly outnumbered, and a German officer and a small party actually got into our trench at the other end. I heard the row and, leaving the gun with Willis, was just in time to see a man kill the officer with his bayonet and the others cleared off again. They were very close all round us now, and as we could see nothing I told the men to keep their ammunition and then split them up, some to shoot forward and some to shoot back. I was frightened that we should be bombed, and surely enough they started, but the throwing was rotten.

And then once more they tried us. A bomb came right in the trench and laid out two more men, splashing me with blood. We shot like fiends and the gun was nearly red-hot, but they were too many. About eight men got into the trench and then we all went mad. It would be impossible for me to give an accurate description because there was just one fierce wild tussle, they trying to get at Willis and that blessed gun and we trying to keep them off. We were too mixed to shoot; they used a sort of life-preserver and we used our bayonets taken off the rifles. A German about my own size slipped into the trench behind me and I just turned in time to duck under a swing from his preserver. What I was doing I shall never know, but by instinct I got my left hand on his throat, and before I knew what had happened I had got the bayonet dagger-wise a good six inches into his chest. He went down without a groan. There was no one in front of me and I turned to find a big Hun with his back to me and a life-preserver raised to hit McDonald, who had his back to the Hun, over the head. If I had had sense I would have stuck the bayonet into his back, but I was absolutely wild and dropped it. Before the Hun could strike I got my hands on his throat and we fell down together. I fell underneath but got on top and pressed until I thought my fingers would break. He was terribly strong and once scratched a great piece out of my left cheek. Gradually he weakened, and I kept my fingers on his throat until he died.

Much the same thing had happened to all the other men except one, who got badly mauled about the head and died shortly afterwards. For a moment I felt we could fight the whole German army, especially when I saw McDonald smash in a German head with the rum jar. Now the survivors were shouting for help, but that blessed Willis (ex jail-bird) was sitting with the gun out in the open, regardless of everything, swearing like hell, and none of the Huns seemed anxious to accept the invitation. We were all clean crazy, and I even had a job to keep the men in the trench. McDonald said something about Cox’s missus, and wanted to kill ten of the “bloody bastards.”

During the whole of that bloody night my hardest job was to restrain the men in that moment of semi-victory; for it was still two hours until dawn. Nine out of the nineteen of us were either dead or dying, and all the rest of us were damaged in some way. Throughout the whole night I had never thought of anything but death. Relief, I knew, was impossible—if we surrendered they would kill us, and I never dreamed that we could really hold them off till dawn. Writing now, it would be easy to imagine impressions which I never really experienced, but I can safely say that throughout the whole night I calmly regarded myself as a dead man. It seemed quite natural that I should be, and I can’t remember that I had the slightest regret. It even seems now that in some queer way I was distinctly happier and more tranquil than I had ever been in my life before. I felt nobler, mightier, than any human being on earth, and death seemed welcome as the only fitting end. Recalling some of my previous entries on the subject of war, I cannot understand my feelings on this occasion and can only repeat that it was so—perhaps something of

“The stern joy which warriors feel

In foemen worthy of their steel.”

It was therefore almost with a feeling of annoyance, of having been cheated of something, that I saw the first streaks of gray beyond Kemmel. I thought they would still make a last effort and waited, but we shivered in vain. In the semi-light we managed to get an odd shot at some of them who had been behind us as they went round to the front—we shot two or three more this way. Then I left my sergeant in charge and went back for a crawl to see what I could find. It was almost light now, and after about half an hour I came across a picket. They firmly believed we were all dead, and said so, and once more that odd feeling of annoyance returned. I remembered that during the night I had visualised the Brigade report on the whole business: “Their Lewis gun was heard firing until early in the morning but it was impossible to reach them.”

However, I went back, left some fresh men in the post and brought my fellows out, leaving orders for the dead to be brought down during the day if possible. As we went back past Brigade I dropped in to report. The General had apparently been up all night and looked very worried. He insisted on seeing the men. They were lying in the mud outside, bleeding and swearing—an awful but a sublime picture. He was deeply moved, and several times under his breath I heard him say, “Marvellous, marvellous, wonderful.” Afterwards, I was told that there were tears in his eyes when he went back into the dug-out. He has had an awful time, poor beggar.

Aug. 12. Had my face dressed and slept like a baby during the day. At night Brigade reported once more that we held a line of connected posts, and again we went out to try to strengthen them. My party started to wire the Merryway post and barricade the road, and Day went forward with a party on the right. When he got forward to where our wire should have been he found a German party well dug-in—fully 100 yards more forward than they were expected to be. They turned a gun on Day’s party and threw about a dozen bombs at them but he got all his fellows back with only two casualties, and these were brought in later. On my side the covering party were so nervous as to be absolutely useless, so I sent them back, and after that my own revolver was the only cover which the men had.

I was crawling about some 50 yards in front of the party when a light went up and I spotted three Huns crouching in a shell-hole with a machine-gun. I had no bombs, so I went back and told the infantry officer, but he wouldn’t do anything. We ceased work about 25 yards away from them.

We found the mutilated body of an infantry officer who was killed on the 11th and brought it in.

On calling at H.Q. on the way back we were informed, as we now knew to our cost, that our posts were all much farther back than was at first thought, and in some places the Huns were even on the near side of our wire. But for our great good luck in getting bombed we should probably have gone out and wired between the German outposts and their main line.

I have seldom known the line to be in a more chaotic state, and I think one more attack would just about put us beyond the count. Every one is nervous, and no one knows where anybody else is.

Aug. 13. Went out after dusk with an infantry subaltern to try to get in touch with a post reported to be on the left of the Merryway post. We groped about without success and eventually saw about 20 figures moving about in one of the camps behind us. They were not more than 30 yards away, so we took them for men from the post we were in search of and did not challenge. Presently they began to move away down the hedge towards the German lines, and my companion remarked that they were going a long way forward, as a German post was known to exist at the corner. Almost immediately afterwards they began to run and disappeared into a trench about 50 yards away. Soon after this we found our own post, and they reported having no men out and having seen no one! There was only one possible conclusion—we had been in close touch with a strong German patrol which had been moving about with the greatest audacity at least 50 yards behind our lines. Very unpleasant to think about.

Then we took a few of the better men and went out on a hunt, but found nothing. It was impossible to wire because of very frequent lights and heavy machine-gun fire. On the right of the track we could find neither Huns nor our own people, and it appears that Brigade H.Q. don’t really know anything about the situation at all. It is in a mess. About 3 a.m. the Huns put down a heavy barrage but didn’t come over.

Aug. 14. Had a night in bed—the third in six weeks. Heard that my infantry friend was killed, just after I left, by our own shrapnel bursting short.

Hear also that I have been recommended for a D.S.O. for the scrap the other night. This is the second time, and it is now some comfort to be definitely sure that they will never give it me.

I would like to get something just for my father’s sake, but for myself—I should almost hate it.

We are here to do a job, not to earn medals for the sake of being gushed over by silly, simpering women who could never understand.

It is a hard creed and difficult to stand by at times—vanity is very strong.

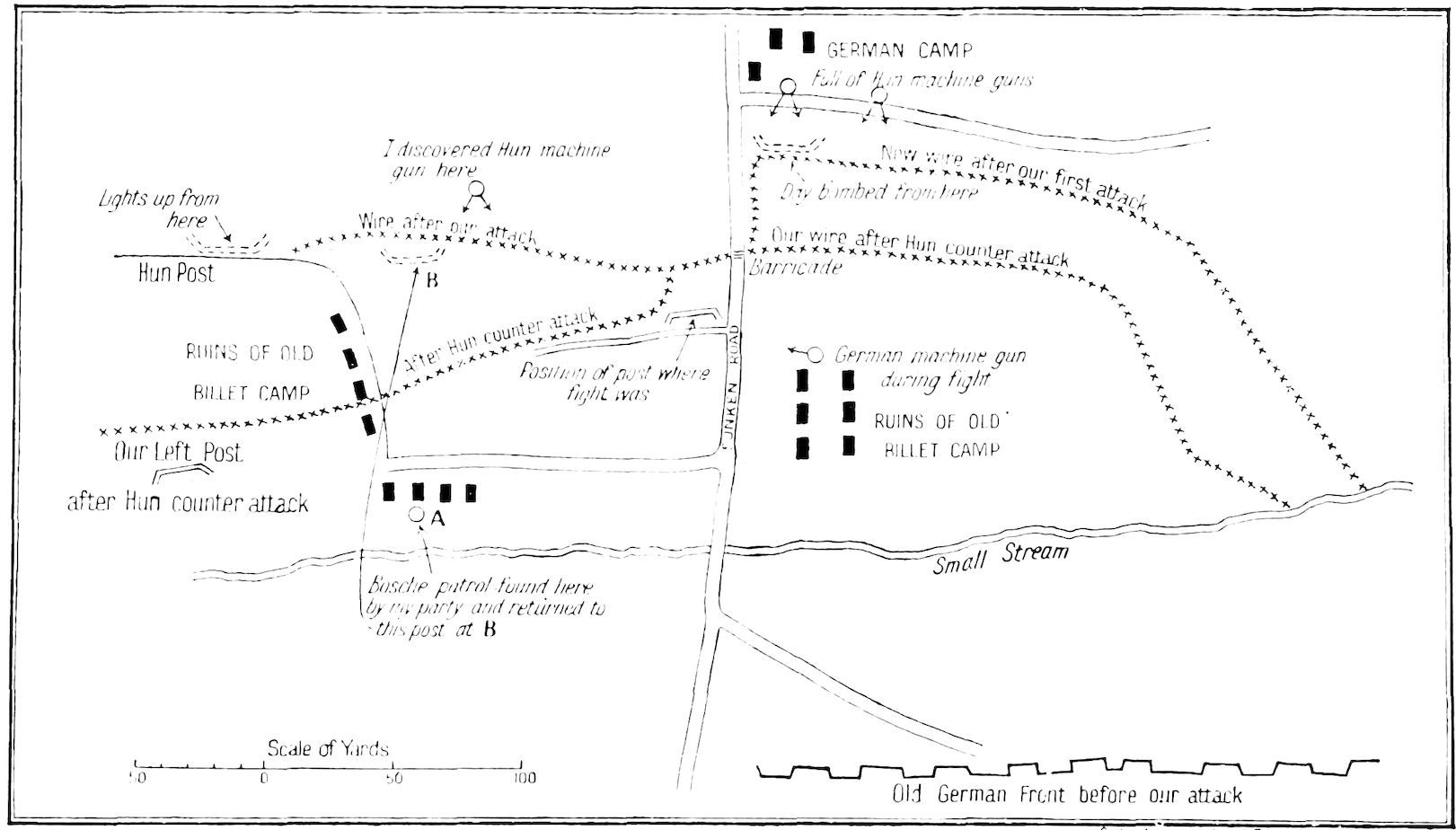

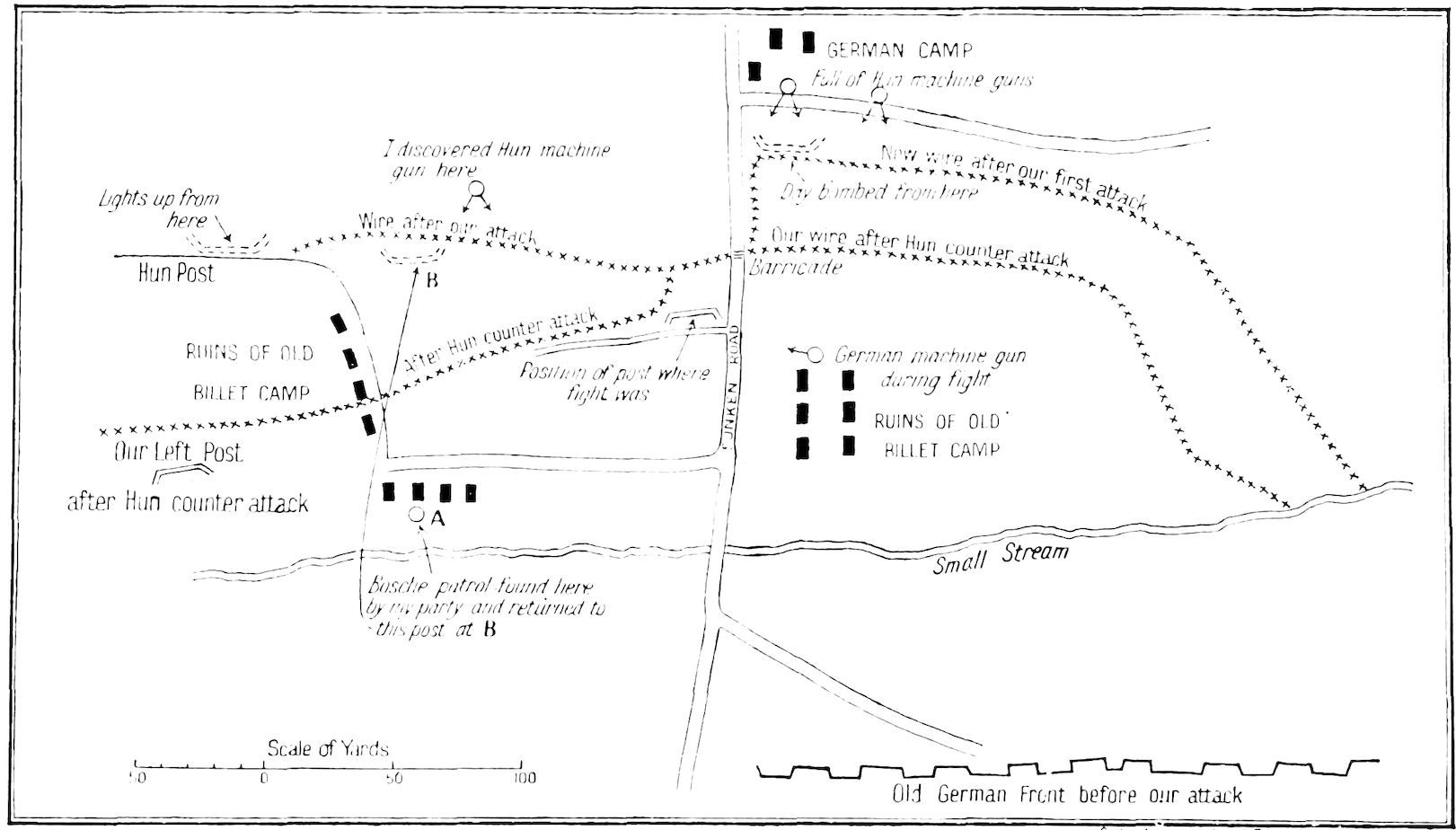

The following shows roughly some of the main points in the Merryway fighting.

Aug. 15. Started to wire from the barricade towards the right in order to join up with Day, who was working from the other end. Got to our first post but could get no farther, as there was a strong German post across our line. Day bumped into this from the other side, and was driven off with two casualties. I was lying down listening when the Huns fired into Day and was surprised to find I was not ten yards away from them. They sent up a light, and I could see about ten of them as plainly as daylight, all looking along their rifles. I dropped a bomb into them and departed, but if we had known they were there we could have collared the whole lot.

Aug. 16. Was relieved at Merryway and spent the night wiring in the right sector—quite a rest cure.

Aug. 17. Wiring again in front of County Camp. Shelled off the job three times and had two casualties, so decided to work the wood instead—shelled again.

Aug. 18. Quiet night in the wood. Slowly and surely I am breaking up, and now I am so far gone that it is too much trouble to go sick. I am just carrying on like an automaton, mechanically putting up wire and digging ditches while I wait, wait, wait for something to happen—relief, death, wounds, anything, anything in earth or hell to put an end to this, but preferably death. I am becoming hypnotised with the idea of Nirvana—sweet, eternal nothingness. My body crawls with lice, my rags are saturated with blood, and we all “stink like the essence of putrefaction rotting for the third time.”

And there are ladies at home who still call us heroes and talk of the Glory of War—Christ!

Collins’ Geographical Establishment, Glasgow.

“If the lice were in their hair,

And the scabs were on their tongue,

And the rats were smiling there

Padding softly through the dung.

Would they still adjust their pince-nez

In the same old urbane way

In the gallery where the ladies go?”

Last night something went wrong in my head. A machine-gun was turned on us, and instead of ducking I remember standing up and being quite interested in watching the bullets kick sparks off the wire—Day pulled me down into a hole and has been watching me ever since.

If ever again I hear any one say anything against a man for incapacitating himself in any way to get out of this I will kill that man. Not even Almighty God can understand the effort required to force oneself back into the trenches at night—I would shoot myself if it were not for the thought of my father—O God! why won’t you kill me?

“To these from birth is Belief forbidden.

From these till Death is Relief afar.”

And the pity of it all is this—that nobody will ever understand! It is hell to be able to see these things, but in two years I know it will all be forgotten. “It is over,” they will say, “we must forget it, it was so terrible.” The world will go back into the old grooves, without honour, without heroism, without ideals, and these dear, darling fellows of mine will be “factory men” once more.

Even now Hardy’s sister is selling matches in Ancoats, and my sister would refer to her as “that woman”—yet Hardy and I have saved each other’s lives. And if I live they will say “Poor old beggar, he isn’t much use now, he had rather a bad time in the war,” and they will pity me—once a month when I am ill. Or, worst of all, if my vitality should come back to a certain extent I will appear quite normal and they will call me a slacker if I don’t take part in games—I, who once captained one of the best Rugby teams in the north! Perhaps they will even be so good as to make allowances for me!

And they will call me dull and morose and cynical—and even priggish when I keep myself aloof from them.

And the ladies for whom I gave my strength and more will leave me for the healthy, bouncing beggars who stayed at home—even as nationally the Neutrals get the good things now. And there are thousands worse than I—may we all die together in one final bloody holocaust and before the Peace Bells usher in the realisation of our fears.

And then, on howling winter evenings, our spirits might ride the cloud-wrack over these blood-soaked hills, shrieking and moaning with the wind, to drown the music of their dancing, so that they huddle together in terror, the empty-headed women and the weak-kneed, worn-out men as we laugh at their petty, soulless lives.

Within a week I shall be dead or mad.

Aug. 19. Very hot to-day—feeling feverish and weak—what futile words!

Aug. 20. Division on our right attacked and captured objectives. Three lines in the Daily Mail to-morrow—three hundred corpses grinning at the stars to-night—in three years oblivion—War!

Aug. 21. Working on Ferret Farm. On way up Fritz got six shells bang into the middle of the parties in the sunken road—one sapper and several P.B.I. hit and Day badly damaged in the face with a stone.

The limber horses behaved wonderfully, and one team didn’t move an inch although a shell burst right under their tail board. Very lucky not to have had lots more casualties. On the track we were shelled again and had to pass through heavy gas in the region of the stream. Almost immediately after starting work Bosche put down a heavy barrage and we lay on our faces for three-quarters of an hour. Heavy shelling continued all night with a lot of machine-gun fire and gas. Was busy with casualties all night and feel like a corpse myself now.

Aug. 22. Beastly hot day and was tortured to death in the evening by mosquitoes—during this warm weather one usually knocks about in the day-time in one’s shirt which becomes saturated with sweat, and then dries off again in the cool of the evening—the mosquitoes love the stink and after dusk they feed on us in millions—there is no respite, you grow tired of killing them and dawn finds you on the edge of insanity, swollen like a long-dead mule. It is these things which constitute the horror of war—death is nothing.

Wrote a cheerful letter home saying that I am very well and happy.

Aug. 23. Was riding up last night through a strafe with Day when a gas shell exploded just in front of our bicycles—we jumped off at once but before we could get our bags on we swallowed rather a large dose—didn’t worry very much and carried on with the night’s work.

Aug. 24. In the morning bust up completely and spent the day in bed—pulled myself together and managed to get up the line again at night.

Aug. 25. Riding home this morning we encountered a sudden whizz-bang strafe on the road, and Day took a small fragment clean through his handle-bars—rained hard all night and practically stopped work.

Aug. 26. Still raining heavily, and we notice the first signs of the return of the mud era—surely they must relieve us now if there is a man to spare in France or England—otherwise, I am afraid a week of heavy rain would clear the road to Calais. For myself, I am too far gone to pick the lice out of my shirt—I have ceased to be a man—even my simian ancestors used to remove their parasites.

Aug. 27. Still raining hard, but news comes through that we are going to be relieved—as I am the only officer that really knows the forward work I am to stay and hand over—only three more nights!

Aug. 28. Very busy day handing over all rear work to relieving company—the attached infantry parties returned to their units to-day.

Aug. 29. Company transport left at 10 a.m. for Rest Area—the Sappers marched off at 1.30 p.m. To-night is to be my last night in the line, I hope, for a fortnight at least.

Aug. 30. Oddly enough, my last night was one of the most eventful spent in the sector. It was a misty night, and I was crawling about with the relieving officer to show him Day’s front line Coy. H.Q., when we were shelled fairly heavily—to avoid the disturbance I made a detour of about 100 yards and got completely lost. Eventually we heard muffled voices behind us, and to my surprise, when I crawled back to investigate, I found a Hun machine-gun post with about six men in it.

We avoided this and eventually struck our own line about a quarter of a mile out of our course—they handled us rather roughly in the trench as they believed us to be Bosche, particularly as my friend knew nothing about the line. After sitting for twenty minutes with two bayonets in my ribs, Miller of the Fusiliers came up and fortunately he knew me. Just managed to complete handing over before dawn and got back for breakfast with our reliefs. Left billets on horseback with Dausay as groom at 11.45. Passed through reserve billets and had an afternoon halt to water the horses in a charming meadow just beyond Cassel. We reached the company about 6 p.m. at a small village outside St. Omer—a very pleasant but a tiring ride.

Day and I are living in a large white château—steeped in romance from its turrets to its, no doubt, well-stocked cellars. Outside my bedroom window there is a balcony where I can sit in the evenings and watch the sun set beyond St. Omer—if only I had my books I might recapture myself in a fortnight here.

Sept. 1. Quiet day, with the usual inspections and cleaning parades. In the evening Major and I rode over to take dinner with the C.R.E.—information had just come through that our outposts are on the top of Kemmel Hill. Apparently the Huns have retreated, but it makes me damn wild to think that we should hold that blood-soaked line and wear down his resistance for other people to follow him up—I would have sold my soul to see the old Division go over Kemmel, and if any one had the right it was we.

Sept. 2. Went into St. Omer with Day and had tea at the club—succeeded in obtaining some butter at 15 francs per kilo—verily the French are a hospitable people! Returned to the mess to find the rumour about Kemmel is confirmed—apparently the Bosche are evacuating forward positions with a view to consolidating their line for the winter. This is all very cheerful and no doubt makes good reading in the clubs at home, but unfortunately it necessitates our return to the line to-morrow—our rest has therefore been a deal of extra trouble for nothing—two days out of the line do one more harm than good. Transport and pontoons started on their return journey to-night.

Sept. 3. Entrained at 8.15 a.m. and detrained at rail-head about 12 noon. Marched forward past our old billets and eventually took over very comfortable billets from a company of American Engineers. The line seems to have gone far forward, all the old gun positions are empty and the sausages are well in front of us now.

After all, I think that the ability to park our transport in the open in full view of Kemmel will do us more good than the “rest” could ever have done. The shadow of that ghastly hill has been over us for so long that our relief at having regained it is out of all proportion to its practical value. The effect on the men has been little short of miraculous, and already they are joking about the possibilities of Christmas at home—or at the worst in Berlin! Once more we look forward to the possibilities of a semi-victory, and the dog-like fatalism which upheld us through the weary summer is gradually changing to something like Hope and Confidence in the Future.

But we can never again go forward with the same fiery ardour and implicit faith in the Justice of our Cause, which drove us onwards in the early days. We have seen brave Germans die with faith as great as ours, and, knowing their intelligence to be not less, we must at least doubt the validity of our first conclusions. Now we are infinitely wiser men, growing sadder as the cold light of reason destroys our early phantoms of enthusiasm. Already “the bones about the way” are far too numerous to justify the best of possible results and—there will be more before the end.

But these reflections are morbid and unbecoming in a soldier—to-morrow I must inspect rifles with enthusiasm.

Sept. 4. Day and I working all day on our dug-out and in making a place where we can have a bath—I shudder when I try to recall my last one.

Sept. 5. Up at 2 a.m. and working until 10 with the whole company endeavouring to construct a road across a semi-dry lake. It is obviously a staff project and would have been condemned by a first year civil-engineering student—we cast our brick upon the waters in the vain hope that it will return after many days.

Meanwhile the advance creeps forward across the swamps in front and shows signs of being bogged as the resistance stiffens.

Yesterday our two line brigades had 500 casualties, and after gaining the summit of Messines Ridge they had to fall back owing to lack of support. Thus it seems that we shall play the German game once more by following them into the worst of the mud for the winter—God help us if we do, the 19–year olds would die like flies in a hard winter.

Had my bath and feel like a new man.

Sept. 6. Dumped a few more tons of brick into the lake—at least it is a peaceful job and keeps the men out of mischief. Played Badminton and wrote letters—the war seems to have fallen into abeyance.

Sept. 7. Heavy gas-shelling on the lake this morning robbed us of our constitutional and forced an early return.

After dinner we turned out with torches and heavy sticks to hunt rats round the dug-outs. There were no casualties among the rats, but Day sprained an ankle.

Sept. 8. Still brick dumping, although no progress is apparent as yet. During the morning I walked across the dyke to talk to the company working in the morass on the far side and sincerely wished I hadn’t. They had been finding bodies all morning, not more than a month dead and just coming to the worst stages. Whilst I was there, they picked up two kilted officers—glorious big men they must have been but looking so childishly pathetic as they lay there. Unconsciously we all fell silent, and I saw a D.C.M. Sergeant-Major with tears in his eyes. Hurriedly I turned away and, walking back to the