CHAPTER III.

PIRATES—DAVIS, ROBERTS, AND OTHERS—BRITISH CRUISERS—SLAVE-TRADE SYSTEMATIZED—GUINEAMEN—“HORRORS OF THE MIDDLE PASSAGE.”

The second period is that of villany. More Africans seem to have been bought and sold, at all times of the world’s history, than of any other race of mankind. The early navigators were offered slaves as merchandise. It is not easy to conceive that the few which they then carried away, could serve any other purpose than to gratify curiosity, or add to the ostentatious greatness of kings and noblemen. It was the demands of the west which rendered this iniquity a trade. Every thing which could debase a man was thrust upon Africa from every shore. The old military skill of Europe raised on almost every accessible point embattled fortresses, which now picturesquely line the Gulf of Guinea. In the space between Cape Palmas and the Calabar River, there are to be counted, in the old charts, forts and factories by hundreds.

The seventeenth and eighteenth centuries were especially the era of woe to the African people. Crime against them on the part of European nations, had become gross in cruelty and universal in extent. From the Cape of Good Hope to the Mediterranean, in respect to their lands or their persons, the European was seizing, slaying and enslaving. The mischief perpetrated by the white man, was the source of mischief to its author. The west coast became the haunt and nursery of pirates. In fact, the same class of men were the navigators of the pirate and the slaver; and sailors had little hesitation in betraying their own vessels occasionally into the hands of the buccaneer. Slave-trading afforded a pretext which covered all the preparations for robbery. The whole civilized world had begun to share in this guilt and in this retribution.

In 1692, a solitary Scotchman was found at Cape Mesurado, living among the negroes. He had reached the coast in a vessel, of which a man named Herbert had gotten possession in one of the American colonies, and had run off with on a buccaneering cruise; a mutiny and fight resulted in the death of most of the officers and crew. The vessel drifted on shore, and bilged in the heavy surf at Cape Mesurado.

The higher ranks of society in Christendom were then most grossly corrupt, and had a leading share in these crimes. There arrived at Barbadoes in 1694, a vessel from New England, which might then have been called a clipper, mounting twenty small guns. A company of merchants of the island bought her, and fitted her out ostensibly as a slaver, bound to the island of Madagascar; but in reality for the purpose of pirating on the India merchantmen trading to the Red Sea. They induced Russell, the governor of the island, to join them in the adventure, and to give the ship an official character, so far as he was authorized to do so by his colonial commission.

A “sea solicitor” of this order, named Conklyn, arrived in 1719 at Sierra Leone in a state of great destitution, bringing with him twenty-five of the greatest villains that could be culled from the crews of two or three piratical vessels on the coast. A mutiny had taken place in one of these, on account of the chief’s assuming something of the character and habits of a gentleman, and Conklyn, after a severe contention, had left with his desperate associates. Had he remained, he might have become chief in command, as a second mutiny broke out soon after his departure, in which the chief was overpowered, placed on board one of the prize vessels, and never heard of afterwards. The pirates under a new commander followed Conklyn to Sierra Leone. They found there this worthy gentleman, rich, and in command of a fine ship with eighty men.

Davis, the notorious pirate, soon joined him with a well-armed ship manned with one hundred and fifty men. Here was collected as fruitful a nest of villany as the world ever saw. They plundered and captured whatever came in their course. These vessels, with other pirates, soon destroyed more than one hundred trading vessels on the African coast. England entered into a kind of compromise, previously to sending a squadron against them, by offering pardon to all who should present themselves to the governor of any of her colonies before the first of July, 1719. This was equivalent to offering themselves to serve in the war which had commenced against Spain, or exchanging one kind of brigandage for another, by privateering against the Spanish commerce. But from the accounts of their prisoners very few of them could read, and thus the proclamation was almost a dead letter.

In 1720, Roberts, a hero of the same class, anchored in Sierra Leone, and sent a message to Plunket, the commander of the English fort, with a request for some gold dust and ammunition. The commander of the fort replied that he had no gold dust for them, but that he would serve them with a good allowance of shot if they ventured within the range of his guns; whereupon Roberts opened his fire upon the fort. Plunket soon expended all his ammunition, and abandoned his position. Being made prisoner he was taken before Roberts: the pirate assailed the poor commander with the most outrageous execrations for his audacity in resisting him. To his astonishment Plunket retorted upon him with oaths and execrations yet more tremendous. This was quite to the taste of the scoundrels around them, who, with shouts of laughter, told their captain that he was only second best at that business, and Plunket, in consideration of his victory, was allowed to escape with life.

In 1721, England dispatched two men-of-war to the Gulf of Guinea for the purpose of exterminating the pirates who had there reached a formidable degree of power, and sometimes, as in the instance noted above, assailed the establishments on shore. They found that Roberts was in command of a squadron of three vessels, with about four hundred men under his command, and had been particularly active and successful in outrage. After cruising about the northern coast, and learning that Roberts had plundered many vessels, and that sailors were flocking to him from all quarters, they found him on the evening of the third of February, anchored with his three vessels in the bay north of Cape Lopez.

When entering the bay, light enough remained to let them see that they had caught the miscreants in their lair. Closing in with the land the cruisers quietly ran in and anchored close aboard the outer vessel belonging to the pirates. Having ascertained the character of the visitors, the pirate slipped his cables, and proceeded to make sail, but was boarded and secured just as the rapid blackness of a tropical night buried every thing in obscurity. Every sound was watched during the darkness of the night, with scarcely the hope that the other two pirates would not take advantage of it to make their escape; but the short gray dawn showed them still at their anchors. The cruisers getting under way and closing in with the pirates produced no movement on their part, and some scheme of cunning or desperate resistance was prepared for. They had in fact made a draft from one vessel to man the other fully for defence. Into this vessel the smaller of the cruisers, the Swallow, threw her broadside, which was feebly returned. A grape-shot in the head had killed Roberts. This and the slaughter of the cruiser’s fire prepared the way for the boarders, without much further resistance, to take possession of the pirate. The third vessel was easily captured.

The cruisers suffered no loss in the fight, but had been fatally reduced by sickness. The larger vessel, the Weymouth, which left England with a crew of two hundred and forty men, had previously been reduced so greatly as scarcely to be able to weigh her anchors; and, although recruited often from merchant vessels, landed but one hundred and eighty men in England. This rendered the charge of their prisoners somewhat hazardous, and taking them as far as Cape Coast Castle, they there executed such justice as the place could afford, or the demerits of their prey deserved. A great number of them ornamented the shore on gibbets—the well-known signs of civilization in that era—as long as the climate and the vultures would permit them to hang.

Consequent on these events such order was established as circumstances would admit, or rather the progress of maritime intercourse and naval power put an end to the system of daring and regulated piracy by which the tropical shores of Africa and the West Indies had been laid waste. This, however, was slight relief for Africa. It was to secure and systematize trade that piracy had been suppressed, and the slave-trade became accordingly cruelly and murderously systematic.

The question what nation should be most enriched by the guilty traffic was a subject of diplomacy. England secured the greater share of the criminality and of the profit, by gaining from her other competitors the right by contract to supply the colonies of Spain with negroes.

Men forget what they ought not to forget; and however startling, disgusting, and oppressive to the mind of man the horrors are which characterized that trade, it is well that since they did exist the memory of them should not perish. It is a fearfully dark chapter in the history of the world, but although terrific it has its value. It is more worthy of being remembered than the historical routine of wars, defeats, or victories; for it is more illustrative of man’s proper history, and of a strange era in that history. The evidence taken by the Committee of the English House of Lords in 1850, has again thrust the subject into daylight.

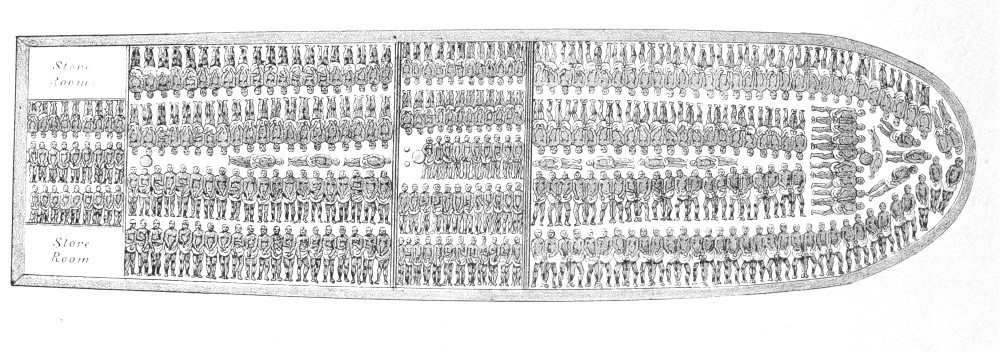

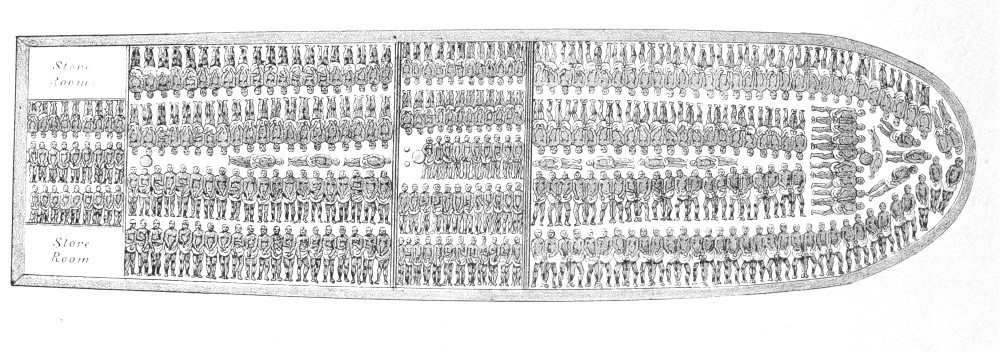

The slave-trade is now carried on by comparatively small and ill-found vessels, watched by the cruisers incessantly. They are therefore induced, at any risk of loss by death, to crowd and pack their cargoes, so that a successful voyage may compensate for many captures. In olden times, there were vessels fitted expressly for the purpose—large Indiamen or whalers. It has been objected to the employment of squadrons to exterminate that trade, that their interference has increased its enormity. This, however, is doing honor to the old Guineamen, such as they by no means deserve. It is, in fact, an inference in favor of human nature, implying that a man who has impunity and leisure to do evil, cannot, in the nature of things, be so dreadfully heartless in doing it, as those in whose track the avenger follows to seize and punish. The fact, however, does not justify this surmise in favor of impunity and leisure. If ever there was any thing on earth which, for revolting, filthy, heartless atrocity, might make the devil wonder and hell recognize its own likeness, then it was on any one of the decks of an old slaver. The sordid cupidity of the older, as it is meaner, was also more callous than the hurried ruffianism of the present age. In fact, a slaver now has but one deck; in the last century they had two or three. Any one of the decks of the larger vessels was rather worse, if this could be, than the single deck of the brigs and schooners now employed in the trade. Then, the number of decks rendered the suffocating and pestilential hold a scene of unparalleled wretchedness. Here are some instances of this, collected from evidence taken by the British House of Commons in 1792.

James Morley, gunner of the Medway, states: “He has seen them under great difficulty of breathing; the women, particularly, often got upon the beams, where the gratings are often raised with banisters, about four feet above the combings, to give air, but they are generally driven down, because they take the air from the rest. He has known rice held in the mouths of sea-sick slaves until they were almost strangled; he has seen the surgeon’s mate force the panniken between their teeth, and throw the medicine over them, so that not half of it went into their mouths—the poor wretches wallowing in their blood, hardly having life, and this with blows of the cat.”

F. E. Forbes, delt.

Lith. of Sarony & Co. N. Y.

THE LOWER DECK OF A GUINEA-MAN IN THE LAST CENTURY.

Dr. Thomas Trotter, surgeon of the Brookes, says: “He has seen the slaves drawing their breath with all those laborious and anxious efforts for life which are observed in expiring animals, subjected, by experiment, to foul air, or in the exhausted receiver of an air-pump; has also seen them when the tarpaulins have inadvertently been thrown over the gratings, attempting to heave them up, crying out ‘kickeraboo! kickeraboo!’ i. e., We are dying. On removing the tarpaulin and gratings, they would fly to the hatchways with all the signs of terror and dread of suffocation; many whom he has seen in a dying state, have recovered by being brought on the deck; others, were irrevocably lost by suffocation, having had no previous signs of indisposition.”

In regard to the Garland’s voyage, 1788, the testimony is: “Some of the diseased were obliged to be kept on deck. The slaves, both when ill and well, were frequently forced to eat against their inclination; were whipped with a cat if they refused. The parts on which their shackles are fastened, are often excoriated by the violent exercise they are forced to take, and of this they made many grievous complaints to him. Fell in with the Hero, Wilson, which had lost, he thinks, three hundred and sixty slaves by death; he is certain more than half of her cargo; learnt this from the surgeon; they had died mostly of the smallpox; surgeon also told him, that when removed from one place to another, they left marks of their skin and blood upon the deck, and that it was the most horrid sight he had ever seen.”

The annexed sketch represents the lower deck of a Guineaman, when the trade was under systematic regulations. The slaves were obliged to lie on their backs, and were shackled by their ankles, the left of one being fettered close to the right of the next; so that the whole number in one line formed a single living chain. When one died, the body remained during the night, or during bad weather, secured to the two between whom he was. The height between decks was so little, that a man of ordinary size could hardly sit upright. During good weather, a gang of slaves was taken on the spar-deck, and there remained for a short time. In bad weather, when the hatches were closed, death from suffocation would necessarily occur. It can, therefore, easily be understood, that the athletic strangled the weaker intentionally, in order to procure more space, and that, when striving to get near some aperture affording air to breathe, many would be injured or killed in the struggle.

Such were “the horrors of the middle passage.”