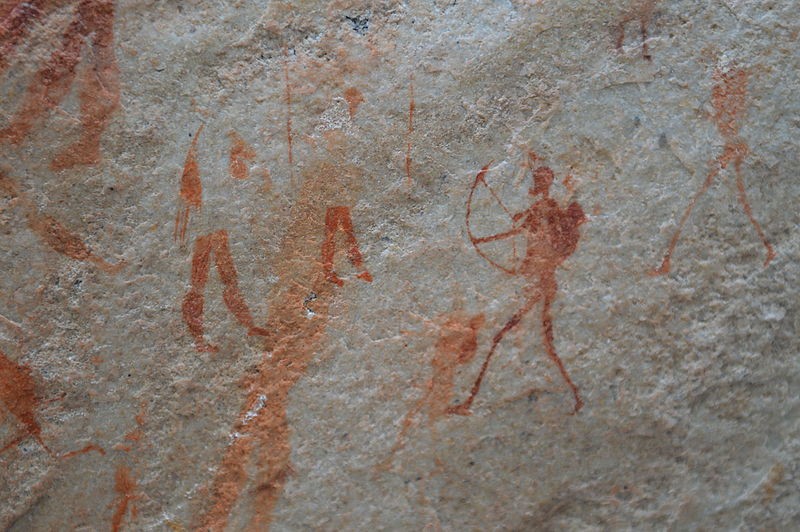

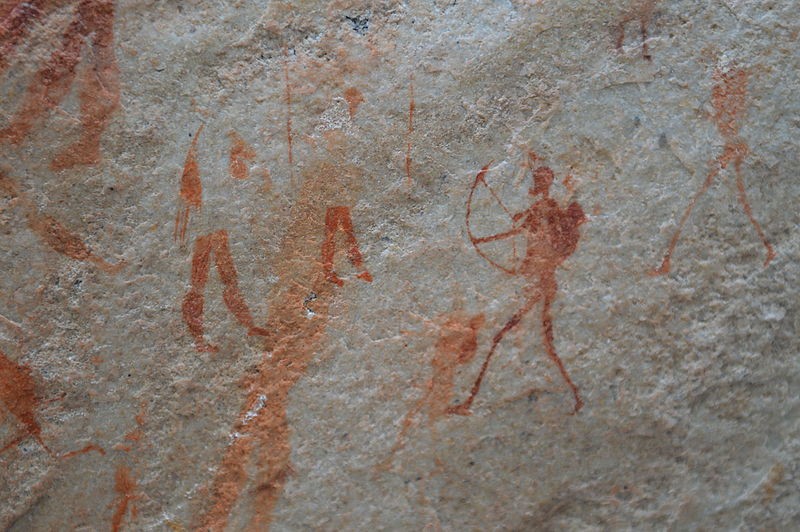

THE INVENTION

Prehistoric San Bushman Rock Art, Cederberg Mountains, Western Cape Province, South Africa. (Photo credit: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sevilla_Rock_Art_9.JPG Author JessyAM (Licensed under CC BY-SA 6.0).)

It was serendipitous that someone in Southern Africa dropped a used bone implement in a hearth and some 61,000 years later the South African archaeologist Dr. Lucinda Backwell would immediately recognize that this bone point was an arrowhead, the kind used well into historical times by the San People.1

The ancient point was studied under a microscope. CT scans were used to look inside. Replicas were made by members of the San, tested on an animal carcass and then subsequently re-analyzed. The high velocity impact damage of the replicas was consistent with the ancient point.

Researchers concluded that the ancient point was used as an arrowhead and later discarded in the hearth.2

Sibudu replicas (Photo: Courtesy of Dr. Lucinda Backwell, University of the Witwatersrand).

In 1926 a San hunting kit was found in a rock shelter in the Mhlwazini valley of South Africa. It was clearly constructed in the not too distant past because some of the arrowheads were made of iron. Other arrowheads were made of bone and are consistent with the ancient Sibudu arrowhead.3

The distance from Mhlwazini valley to the hearth in Sibudu Cave is 120 miles and 61,000 years.

1926 San Hunting Kit. (Image: Courtesy of KwaZulu-Natal Museum, South Africa.)

The Sibudu bone point is not, however, the earliest evidence of the bow-and-arrow. Also found in this cave were 64,000 year old small, sharp, stone blades with one dull side. Analyses of these small blades revealed that some had animal residue and high velocity impact damage that was deemed consistent with their use as arrowheads.4 At a different cave in South Africa 71,000 year old versions of these same projectiles were found.5 None of these sharp blades look much like arrowheads. (There is, however, evidence that this type of projectile may have killed a Neanderthal 50,000 years ago in Northern Iraq,... discussed later.)

The bottom most layer of Sibudu Cave is older than 77,000. Found in this layer were bifacial points the size of arrowheads. Some points retained residue from the Malvaceae shrub whose light, strong and straight stems were used well into historic times as arrow shafts.6

Examples of small blades used for arrowheads (Pitt Rivers Museum, Oxford, England). With one exception there are two blades on each foreshaft (the foreshafts were designed to be inserted into the hollow reed main shaft of an arrow). At least one of these foreshafts (4th from left) was made in historic times for its blades were chipped from bottle glass.7 (Photo: Courtesy of Dr. Justin Pargeter, New York University.)

The bow is not an obvious thing to make nor is it a simple thing to make. What inspired the "Genius of South Africa'' to make such a weapon will never be known. Modern bowyers who re-create the ancient bows are keenly aware of the skill of the ancient bowyers.8 The single most important step is to know your wood for it must be able to withstand the compression force on the inside (“belly”) and the stretching force on the outside (“back”).

There are some 750 native tree species in North America.9 Existing museum artifacts reveal that eight of these trees are known to have been used by Native Americans to make their war/hunting bows.10 Only one tree in nearly a hundred species was good enough.

Two of the eight trees, the Osage Orange and Pacific Yew, excel. Even then the design of the bow is adjusted to reflect the different properties of the wood. The cross section of the bow made from the Osage orange is generally rectangular in shape while the cross section of the bow made from the softer yew tree is made thinner and wider.11 Even the bow staves are cut differently. The yew stave includes the sapwood with the heartwood. When the stave is transformed into the bow, the heartwood becomes the belly and the sapwood the back. The Osage orange stave typically consists only of heartwood. The newer outer growth in the stave becomes the back while the older inner growth is used for the belly. But before work begins, the stave is cured. If not, the bow will have to be oiled (greased with animal fat) and re-tillered as it gets stronger with age.12 For best results the Medieval English cured the wood for their longbows for 4 years.13

The other somewhat lesser trees all have their peculiarities. One design does not fit all. And no matter which wood is selected the cardinal rule of all bowyers, both ancient and modern, is do not cut through a growth ring on the back of the bow for that is where the bow will break.14 And after the stave is transformed into the bow it must be properly shaped. The Hadza of Tanzania place their bows into hot ashes and then use the fork of a tree to straighten the sides and to curve the back.15

The bow string is made from sinew, animal intestines or plant fiber. One method is to first strip the sinew or plant fiber down to 8 or 10 threads and then twist the threads together clockwise making sure that the thread lengths are staggered. After making a second string in the same manner the two strings are then twisted together counter clockwise.16

Making arrows is an art. As with bows the selection of wood for the shaft is critical albeit the selection criteria is different. Straight shoots of the desired wood should be cut in winter. The bark is then peeled and the diameter of the shaft is reduced and straightened by planing. The shafts are then bundled together and allowed to season for 2 to 6 months in a shady dry place. After seasoning, the arrows are reduced to their finished diameter by more careful planing. The finished diameter is measured by a shaft-sizer which is made of bone or wood with a hole the size of the finished diameter drilled through it. Once the arrow shaft has been reduced to the finished size it is straightened by carefully heating and then bending by hand.17

The preparation of feathers and their attachment to the shaft with sinew and glue as well as the manufacture of stone or bone arrowheads and their attachment to the shaft is a time consuming process and this description would be overly tedious. It is sufficient to say it takes a half day to make one arrow from a seasoned shaft.18

Ancient shaft-sizers made of bone are found in museums throughout the world and are labeled “baton de commandement”, whatever that may mean. These are the micrometers of the ancient world and their purpose was to ensure consistent shaft size and therefore projectile performance. According to expert bowyer Jim Hamm he believed that most of these museum pieces were used to size shafts.19 The diameter of the holes in these artefacts do seem to cluster around two ranges, 5-9 mm and 16-30 mm. The smaller for arrow shafts and the larger for darts, javelins and spear shafts with the darts at the lower end of this range.

Baton de commandement found in Veyrier, Switzerland (Museum of Art and History, Geneva, Switzerland). It is ~13,000 years old with a 29 mm hole, the correct size for a spear. (Photo credit:

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:B%C3%A2ton_de_commandement-MAHG_A-8816-P805050 5-gradient.jpg Author Rama (Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 FR).)

In 1950 an elder of the Nez Perce Tribe of North America taught a young boy how to make their tribal bow. The boy learned by watching. The bow was short and powerful. It was made from the horn of the wild sheep. It was the same bow used by the ancestors of the Nez Perce to hunt buffalo. These bows had a draw weight of 70 - 75 pounds and shot fast.20 If not for this one elder and one small boy the art of making this bow would have been lost. Some years later the tribe secured a grant for $50,000 so that the then grown boy could show others the making of this bow. It takes a gap of only a couple generations before young boys have no one to watch.