CHAPTER TWO

How the City grew (Roman Days)

WHO built the first bridge? We cannot say for certain; but it is fairly safe for us to assume that the Romans shortly after their arrival in Llyndin set to work to make a strong wooden military bridge to link up the town with the important road from Dover. Thousands of Roman coins have been recovered from the bed of the Thames at this spot, and we may quite well suppose that the Roman people dropped these through the cracks as they crossed the roughly constructed bridge.

This bridge established London once and for all. Previously there had been the two ferries—that of Thorney (Westminster) and that of Llyndin Hill, each with its own growing settlement. Either of these rivals might have developed into the foremost city of the valley. But the building of the bridge definitely settled the question and caused the diversion of Watling Street to a course across the bridge, through the settlement, out by way of what was afterwards Newgate, and on to Tyburn, where the old way was rejoined.

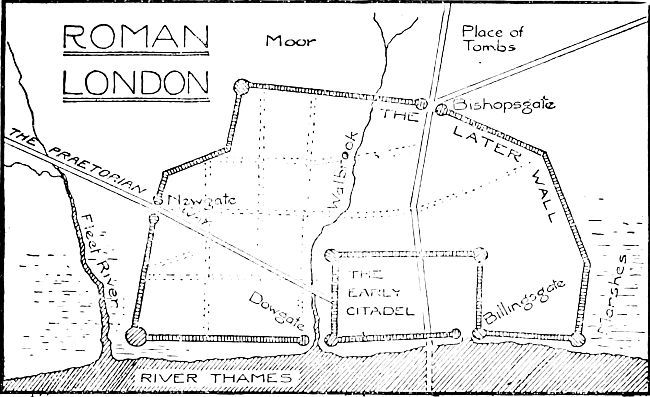

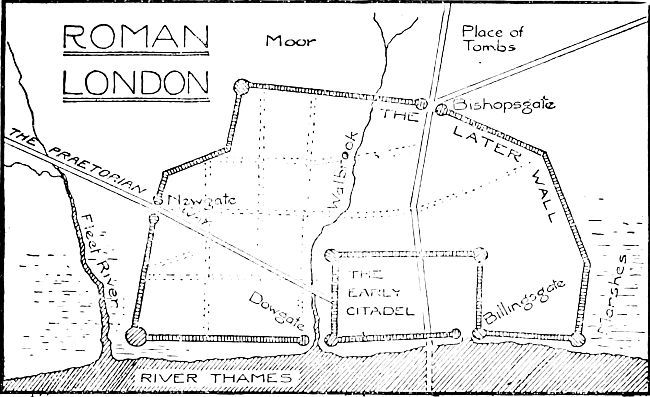

Having built the bridge, they set to work to make of London a city, as they understood it. In all probability it was quite a flourishing place when they found it. But the Romans had their own thoughts about building, their own ideas of what a city should be. First, they built a citadel. The original British stockade stood on the western hummock of the twin hill, so the Romans chose the eastern height for their defences. This citadel, or fortress, was a large and powerful one, with massive walls which extended from where Cannon Street Station now is to where Mincing Lane runs. Inside it the Roman soldiers lived in safety.

Gradually, however, the fortress ceased to be necessary, and a fine town spread out beyond its walls, stretching as far eastwards and westwards as Nature permitted; that is, to the marshes on the east and to the Fleet ravine on the west. In this space were laid out fine streets and splendid villas and public buildings. Along the banks of the River were built quays and river walls; and trade increased by leaps and bounds.

Nor was this all. The Romans, as you have probably read, made magnificent roads across England, and London was practically the hub of the series, which radiated in all directions. The old British road through Kent became the Prætorian Way (afterwards the diverted Watling Street), and passed through the city to the north and west. Another, afterwards called Ermyn Street, led off to Norfolk and Suffolk. Yet another important road passed out into Essex, the garden of England in those days.

“How do we know all these things?” you ask. Partly by what Roman writers tell us, and partly by all the different things which have been brought to light during recent excavations. When men have been digging the foundations of various modern buildings in different quarters of London, they have discovered the remains of some of these splendid buildings—all of them more or less ruined (for a reason which we shall see later), but a few in good condition. Fine mosaic pavements have been laid bare in one or two places—Leadenhall Street for one; and all sorts of articles—funeral urns, keys, statues, ornaments, domestic utensils, lamps, etc.—have been brought to light, many of which you can still see if you take the trouble to visit the Guildhall Museum and the London Museum. In a court off the Strand may still be seen an excellent specimen of a Roman bath.

ROMAN LONDON

But perhaps the most interesting of all the Roman remains are the two or three fragments of the great wall, which was not built till somewhere between the years 350 and 365 A.D. At this time the Romans had been in occupation for several hundred years, and the city had spread quite a distance beyond the old citadel walls. The new wall was a splendid one, twenty feet high and about twelve feet thick, stretching for just about three miles. It ran along the river front from the Fleet River to the corner where the Tower stands, inland to Bishopsgate and Aldersgate, then across to Newgate, where it turned south again, and came to the River not far from Blackfriars.

Several fine sections of the ancient structure can still be seen in position. There is a large piece under the General Post Office yard, another fine piece in some wine cellars close to Fenchurch Street Station, a fair piece on Tower Hill, and smaller remnants in Old Bailey and St. Giles’ Churchyard, Cripplegate.

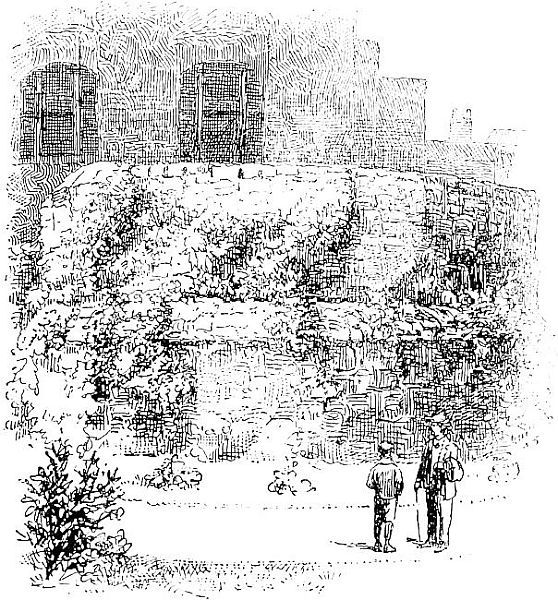

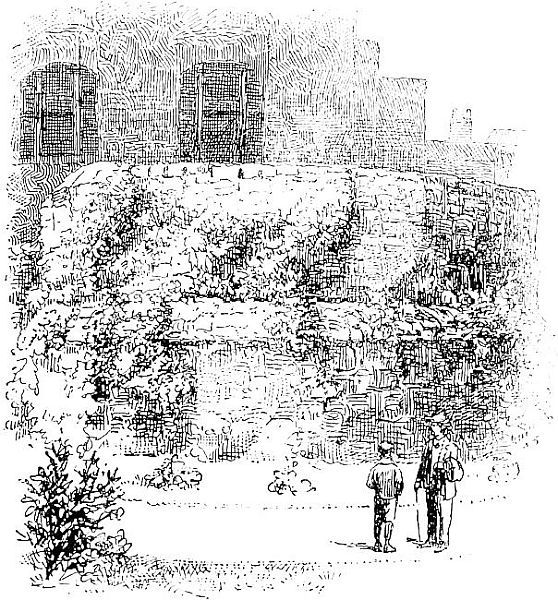

BASTION OF ROMAN WALL, CRIPPLEGATE CHURCHYARD.

What do these fragments teach us? That things were not all they should be in London. Instead of being built with the usual care of Roman masonry, with properly quarried and squared stones, this wall was made up of a medley of materials. Mixed in with the proper blocks were odd pieces of buildings, statues, columns from the temples, and memorials from the burying grounds. Probably the folk of London, feeling that the power of Rome was waning, were stricken with panic, and so set to work hurriedly and with such materials as were to hand to put together this great defence.

Nor were they unwise in their preparations, for danger soon began to threaten. From time to time there swooped down on the eastern coasts strange ships filled with fierce warriors—tall, fair-haired men, who took what they could lay their hands on, and killed and burned unsparingly. So long as the Roman soldiers were there to protect the land and its people, nothing more happened than these small raids. The strangers kept to the coasts and seldom attempted to penetrate up the river which led to London.

But these coast raids only heralded the great storm which was approaching, for the daring sea-robbers had set covetous eyes on the fair fields of Britain.