CHAPTER SIX

Windsor

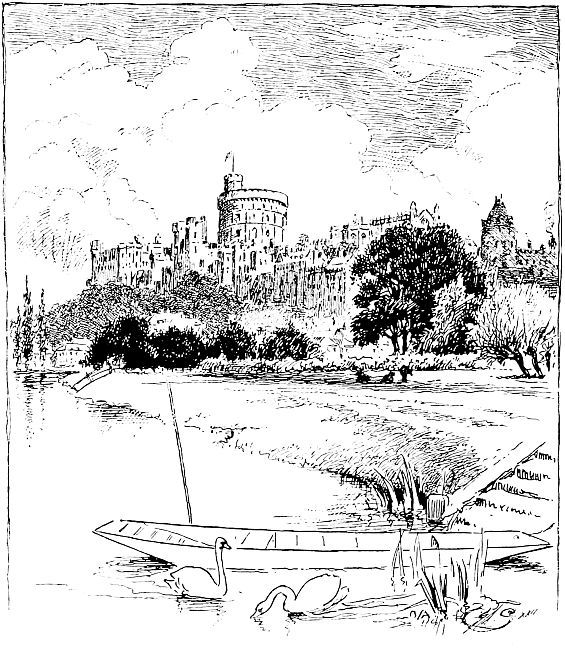

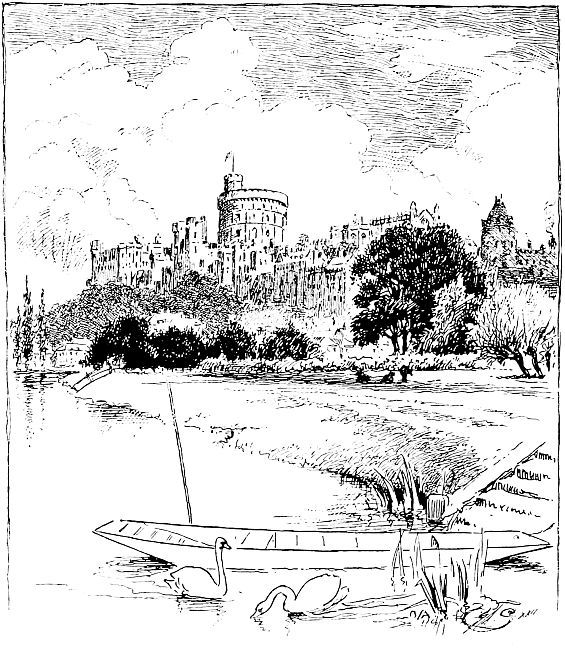

WINDSOR CASTLE, seen from the River at Clewer as we make our way downstream, provides us with one of the most magnificent views in the whole valley. Standing there, high on its solitary chalk hill, with the glowing red roofs of the town beneath and the rich green of the numerous trees clustering all round its base, the whole bathed in summer sunshine, it is a superb illustration of what a castle should be—ever-present, magnificent, defiant.

Yet, despite its wonderful situation, the finest without doubt in all the south of England, Windsor has had little or no history, has rarely beaten off marauding foes, and seldom taken any part in great national struggles. Built for a fortress, it has been through the centuries nothing more than a palace.

Erected by the builder of the Tower, William of Normandy, and probably for the same purpose, it has passed in many ways through a parallel existence, has been just what the Tower has been—an intended stronghold, a prison, and a royal residence. Yet, whereas the Tower has been intimately bound up with the life of England through many centuries, Windsor has, with just one or two brief exceptions, been a thing apart, something living its life in the quiet backwaters of history.

WINDSOR CASTLE.

The Windsor district was always a favourite one with the rulers of the land even before the existence of the Castle. Tradition speaks of a hunting lodge, deep in the glades of the Old Windsor Forest, close by the river, as belonging to the redoubtable King Arthur, and declares that here he and his Knights of the Round Table stayed when they hunted in the greenwood or sallied forth on those quests of adventure with which we are all familiar. What is more certain, owing to the bringing to light of actual remains, is that Old Windsor was a Roman station. Certainly it was a favourite haunt of the Saxon kings, who in all probability had a palace of some sort there, close to the Roman road which passed by way of Staines to the camp at Silchester; and its value must have been thoroughly recognized. Edward the Confessor in particular was especially fond of the place, and when he founded and suitably endowed his wonderful Abbey at Westminster he included “Windsor and Staines and all that thereto belongs” among his valuable grants to the foundation over which his friend Edwin presided.

In those days the Castle Hill was not even named. True, its possibilities as a strategic point were recognized, by Harold if by no other, for we read in the ancient records that Harold held on that spot four-and-a-half hides of land for defensive purposes.

But it remained for William the Conqueror, that splendid soldier and mighty hunter, to recognize the double possibilities of Windsor. Naturally, following his victory, he made himself familiar with Harold’s possessions, and, coming shortly to Windsor, saw therein the means of gratifying two of his main interests. He inspected the ancient Saxon royal dwelling and saw at once its suitability as a retiring place for the King, surrounded by the great forest and quite close to that most convenient of highways, the River. And at the same time, warrior as he was, he understood the value of the little chalk hill which stood out from the encompassing clay.

Certainly it belonged to the Abbey as a “perpetual inheritance,” but to such as William that was not likely to matter much. All England was his: he could offer what he liked. So he chose for exchange two fat manors in Essex—Wokendune and Feringes—fine, prosperous agricultural places, totally different from the unproductive wastelands of Windsor Hill; and the Abbot, wise man that he was, jumped at the exchange. Thus the Church was satisfied, no violence was done, and William secured both the Forest and the magnificent little hill commanding then, as it does now, many miles of the Thames Valley.

Why did he want it? For two reasons. In the first place, he wanted an impregnable fortress within striking distance of London. True, under his orders Gundulf had built the Tower, frowning down on the city of London; but a fortress which is almost a part of the city, even though it be built with the one idea of striking awe into the citizens, is really too close at hand to be secure. A fortress slightly aloof, and therefore not quite so liable to sudden surprise, yet within a threatening distance, had vastly greater possibilities.

William’s other great passion was “the chase.” Listen to what the ancient chronicler said about him: “He made many deer-parks; and he established laws therewith; so that whosoever slew a hart or a hind should be deprived of his eyesight. He loved the tall deer as if he were their father. Hares he decreed should go free. His rich men bemoaned it; and the poor men shuddered at it. But he was so stern, that he recked not the hatred of them all; for they must follow withal the King’s will if they would live, or have land, or possessions, or even his peace.” For this the surrounding forests rendered the position of Windsor a delightful one.

Thus came into existence the Norman Keep of Windsor Hill, and beneath it shortly after the little settlement of New Windsor. When Domesday Book was prepared the little place had reached the number of one hundred houses, and thenceforward its progress was steady. By the time of Edward I. it had developed to such an extent that it was granted a charter—which document may still be seen in the Bodleian Library at Oxford.

With the Kings that came after the Conqueror Windsor soon became a favourite residence. Henry I., marrying a Saxon Princess, Edith, niece of the Confessor, lived there and built a fine dwelling-place with a Chapel dedicated to the Confessor and a wall surrounding everything.

During the reign of John, Windsor was besieged on more than one occasion, and it was from its fastness that the most wretched King who ever ruled—or misruled—England crept out to meet the Barons near Runnymede, just over the Surrey border.

Henry III., finding the old fabric seriously damaged by the sieges, determined to rebuild on a grander scale, and he restored the walls, raised the first Round Tower, the Lower and Middle Wards, and a Chapel; but, save one or two fragments, all these have perished.

However, it is to Edward of Windsor—the third King of that name—that we must look as the real founder of the Windsor of to-day. He rebuilt the Chapel and practically all the structures of Henry III., and added the Upper Ward.

In connection with this last a very interesting story is told. Edward had on the spot two very distinguished prisoners—King David of Scotland and King John of France—rather more like unwilling guests than prisoners, since they had plenty of liberty and shared in the amusements of the Court. One day the two were strolling with Edward in the Lower Ward, taking stock of the new erections, when King John made some such remark as this: “Your Grace’s castle would be better on the higher ground up yonder. You yourself would be able to see more, and the castle would be visible a greater way off.” In which opinion he was backed by the King of Scotland. Edward’s reply must have surprised the pair of them, for he said: “It shall be as you say. I will enlarge the Castle by adding another ward, and your ransoms shall pay the bill.” But Edward’s threat was never carried out. King David’s ransom was paid in 1337, but it only amounted to 100,000 marks; while that of King John, a matter of a million and a half of our money, was never paid, and John returned to England to die in the year 1363 in the Palace of the Savoy.

In the building of Windsor, Edward had for his architect, or superintendent, a very famous man, William Wykeham, the founder and builder of Winchester School and New College, Oxford. Wykeham’s salary was fixed at one shilling a day while at Windsor, and two shillings while travelling on business connected with the Castle. Wykeham’s chief work was the erection of the Great Quadrangle, a task which took him ten years to complete. While there at work, he had a stone engraved with the Latin words, Hoc fecit Wykeham, which translated means “Wykeham made this.” Edward was enraged when he saw this inscription, for he wanted no man to share with him the glory of rebuilding Windsor; and he called his servant to account for his unwise action. Wykeham’s reply was very ingenious, for he declared that he had meant the motto to read: “This made Wykeham” (for the words can be translated thus). The ready answer appeased the King’s wrath.

The method by which the building was done was that of forced labour—a mild form of slavery. Edward, instead of engaging workmen in the ordinary way, demanded from each county in England so many masons, so many carpenters, so many tilers, after the fashion of the feudal method of obtaining an army. There were 360 of them, and they did not all come willingly, for certain of them were thrown into prison in London for running away. Slowly the work proceeded, but in 1361 the plague carried off many of the craftsmen, and new demands were made on Yorkshire, Shropshire, and Devon, to provide sixty more stone-workers each. When at length the structure was completed in 1369, it included most of the best parts of Windsor Castle—the Great Quadrangle, the Round Tower, St. George’s Hall and Chapel, and the outer walls with their gates and turrets.

The Chapel was repaired later on, under the direction of another distinguished Englishman, Geoffrey Chaucer, the father of English poetry, who for over a year was “master of the King’s works” at Windsor. In 1473 the Chapel had become so dilapidated that it was necessary to pull it down, and Edward IV. erected in its place an exceedingly beautiful St. George’s Chapel, as an act of atonement for all the shed blood through which he had wallowed his way to the throne.

Queen Elizabeth was very fond indeed of Windsor, and frequently came thither in her great barge. She built a banqueting hall and a gallery, and formed the fine terrace which bears her name. This terrace, on the north side, above the steep, tree-planted scarp which falls away to the river valley, is an ideal place. Behind rise the State Apartments: in front stretches a magnificent panorama across Eton and the plain. On this terrace the two Charleses loved to stroll; and George III. was accustomed to walk every day with his family, just an ordinary country gentleman rubbing shoulders with his neighbours.

It is a wonderful place, is Windsor Castle—very impressive and in places very beautiful; but there is so much to write about that one scarcely knows where to begin. Going up Castle Hill, we turn sharp to the left, and, passing through the Gateway of Henry VIII., we are in the Lower Ward, with St. George’s Chapel facing us in all its beauty.

This fine perpendicular Chapel is, indeed, worthy of the illustrious order, the Knights of the Garter, for whom it is a place both of worship and of ceremonial.

The Order of the Knights of the Garter was founded by Edward III. in the year 1349, and there were great doings at Windsor on the appointed day—St. George’s Day. Splendid pageants, grand tournaments, and magnificent feasts, with knights in bright armour and their ladies in the gayest of colours, were by no means uncommon in those days; but on this occasion the spectacle was without parallel for brilliance, for Edward had summoned to the great tournament all the bravest and most famous knights in Christendom, and all had come save those of Spain, forbidden by their suspicious King. From their number twenty-six were chosen to found the Order, with the King at their head.

St. George’s Chapel has some very beautiful stained-glass windows, some fine tracery in its roof, and a number of very interesting monuments. The carved stalls in the choir, with the banners of the knights drooping overhead, remind us certainly of the Henry VII. Chapel at Westminster. Within the Chapel walls have been enacted some wonderful scenes—scenes pleasing, and scenes memorable for their sorrow. Here have been brought, at the close of their busy lives, many of England’s sovereigns, and here some of them—Henry VI. and Edward IV. among them—rest from their labours. Queen Victoria, who loved Windsor, lies with her husband in the Royal Tomb at Frogmore, not far away.

The Round Tower, which stands practically in the centre of the clustered buildings and surmounts everything, is always one of the most interesting places. From its battlements may be seen on a clear day no less than twelve counties. We can trace the River for miles and miles as it comes winding down the valley from Clewer and Boveney, to pass away into the distance where we can just faintly discern the dome of St. Paul’s.