CHAPTER ONE

London River

FROM its mouth inwards to London Bridge the Thames is not the Thames, for like many another important commercial stream it takes its name from the Port to which the seamen make their way, and it becomes to most of those who use it—London River.

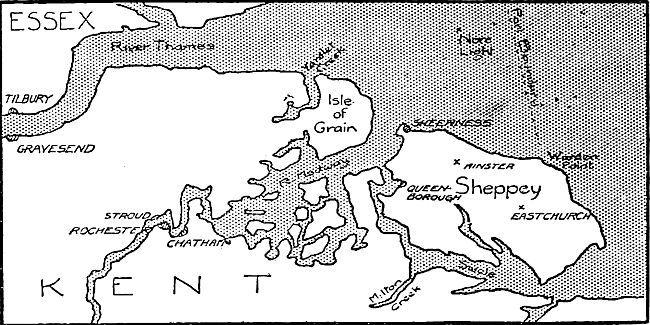

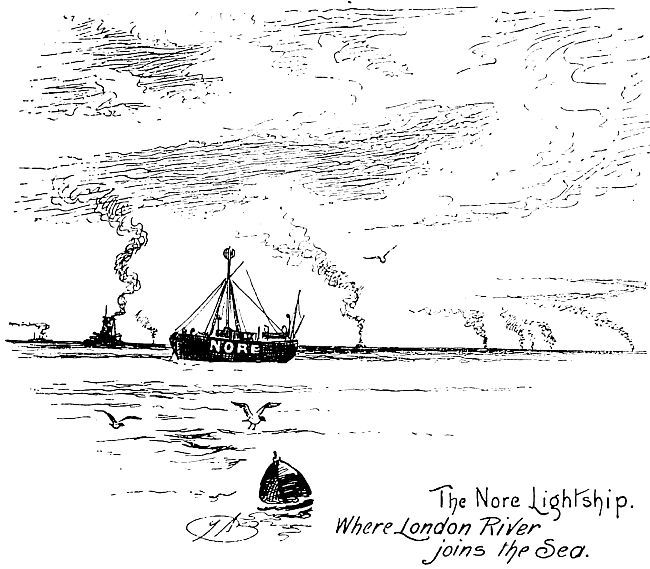

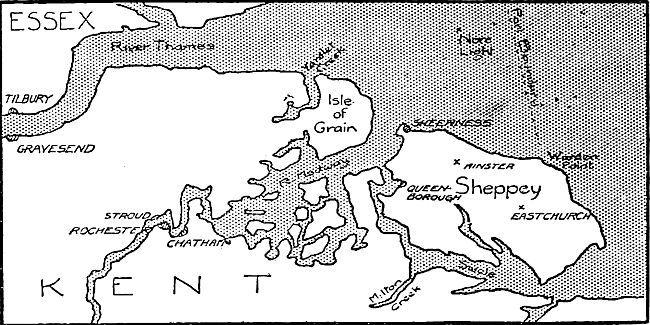

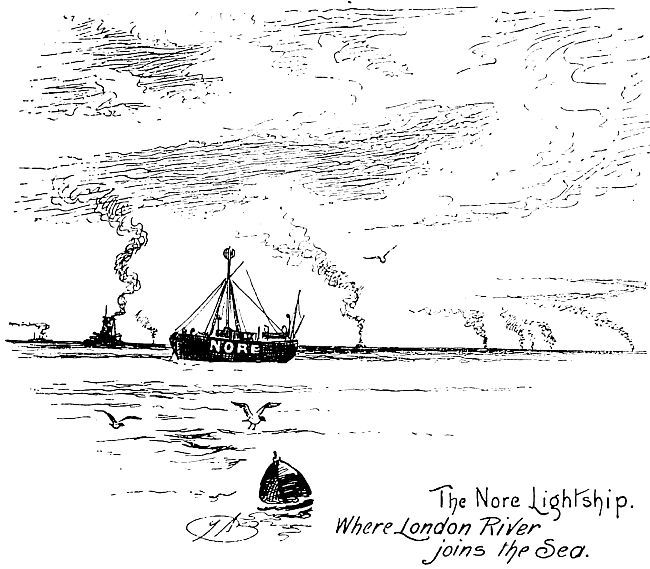

Now where does London River begin at the seaward side? At the Nore. The seaward limit of the Port of London Authority is somewhat to the east of the Nore Light, and consists of an imaginary line stretching from a point at the mouth of Havingore Creek (nearly four miles north-east of Shoeburyness on the Essex coast) to Warden Point on the Kent coast, eight miles or so from Sheerness; and this we may regard quite properly as the beginning of the River. The opening here is about ten miles wide, but narrows between Shoeburyness and Sheerness, where for more practical purposes the River commences, to about six miles.

Right here at the mouth the River receives its last and most important tributary—the Medway.

For some miles up the estuary and the lower reaches the character of the River is such that it is difficult to imagine anything less interesting, less impressive, less suggestive of what the river approach to the greatest city in the world should be; for there is nothing but flat land on all sides, so flat that were not the great sea-wall in position the whole countryside would soon revert to its original condition of marsh and fenland. Were we unfamiliar with the nature of the landscape, a glance at the map would convince us at once, for in continuous stretch from Sheerness and the Medway we find on the Kentish bank—Grain Marsh (the Isle of Grain), St. Mary’s Marshes, Halslow Marshes, Cooling Marshes, Cliffe Marshes, and so on. Nor is the Essex bank any better once we have left behind the slightly higher ground on which stand Southend, Westcliff, and Leigh, for the low, flat Canvey Island is succeeded by the Mucking and East Tilbury Marshes.

The Nore Lightship. Where London River joins the Sea.

The river-wall, extending right away from the mouth to London on the Essex side, is a wonderful piece of engineering—man’s continuously successful effort against the persistence of Nature—a feature strongly reminiscent of the Lowlands on the other side of the narrow seas. Who first made this mighty dyke? No one knows. Probably in many places it is not younger than Roman times, and there are certain things about it which tend to show an even earlier origin.

Indeed, so long ago was it made that the mouth and lower parts of the River must have presented to the various invaders through the centuries very much the same appearance as they present to anyone entering the Thames to-day. The Danes in their long ships, prowling round the Essex and Thanet coasts in search of a way into the fair land, probably saw just these same dreary flats on each hand, save that when they sailed unhindered up the River they caught in places the glint of waters beyond the less carefully attended embankment. The foreign merchants of the Middle Ages—the men of Genoa and Florence, of Flanders and the Hanseatic Towns—making their way upstream with an easterly wind and a flowing tide; the Elizabethan venturers coming back with their precious cargoes from long and perilous voyages; the Dutch sweeping defiantly into the estuary in the degenerate days of Charles II.—all these must have beheld a spectacle almost identical with that which greets our twentieth-century travellers returning from the East.

Sheerness on Sea

Perhaps, at first sight, one of the most striking things in all this stretch of the River is the absence of ancient fortifications. True, we have those at Sheerness, but they were made for the guarding of the dockyard and of the approach to the important military centre at Chatham, which lies a few miles up the River Medway. Surely this great opening into England, the gateway to London, this key to the entire situation, should have had frowning castles on each shore to call a halt to any venturesome, invading force. Thus we think at once with our twentieth-century conception of warfare—forgetting that the cannon of early days could never have served to throw a projectile more than a mere fraction of the distance across the stream.

Not till we pass up the Lower Hope and Gravesend Reaches and come to Tilbury and Gravesend, facing each other on the two banks, do we reach anything like a gateway. Then we find Tilbury Fort on the Essex shore, holding the way upstream. Here, at the ferry between the two towns, the River narrows to less than a mile in width; consequently the artillery of ancient days might have been used with something like effectiveness.

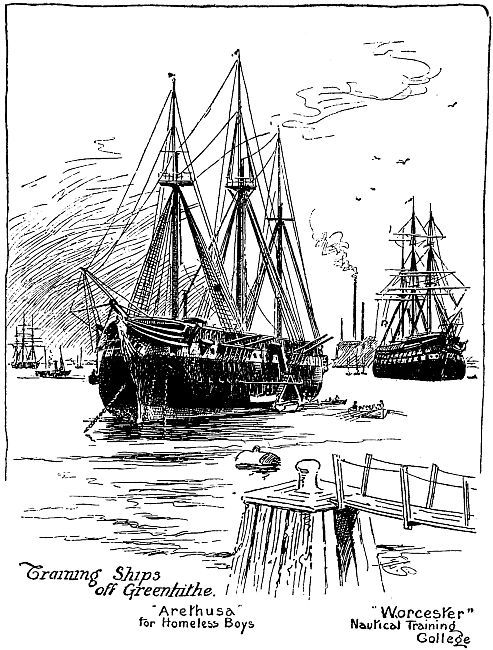

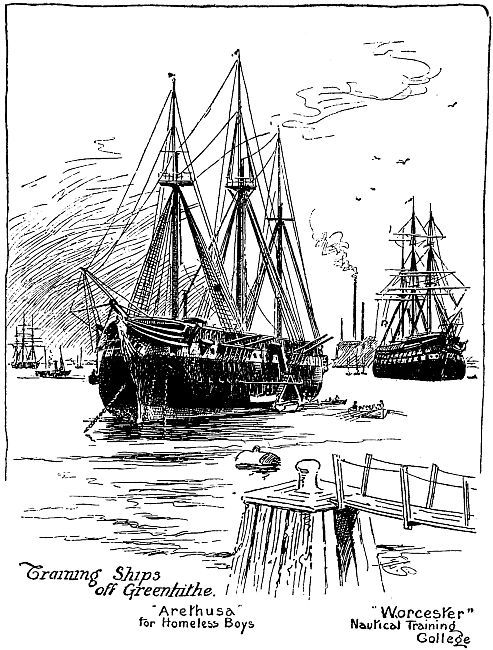

Training Ships off Greenhithe.

“Arethusa” for Homeless Boys

“Worcester” Nautical Training College

From Gravesend westwards the country still lies very low on each bank, but the monotony is not quite so continuous, for here and there, first at one side and then at the other, there rise from the widespread flats little eminences, and on these small towns generally flourish. At Northfleet and Greenhithe, for instance, where the chalk crops out, and the River flows up against cliffs from 100 to 150 feet high, there is by contrast quite a romantic air about the place, and the same may be said of the little town of Purfleet, which lies four miles up the straight stretch of Long Reach, its wooded chalk bluffs with their white quarries very prominent in the vast plain. But, for the most part, it is marshes, marshes all the way, particularly on the Essex shore—marshes where are concocted those poisonously unpleasant mixtures known as “London specials,” the thick fogs which do so much to make the River, and the Port as well, a particularly unpleasant place at certain times in winter. When a “London special” is about—that variety which East Enders refer to as the “pea-soup” variety—the thick, yellow, smoke-laden mist obscures everything, effectively putting an end to all business for the time being.

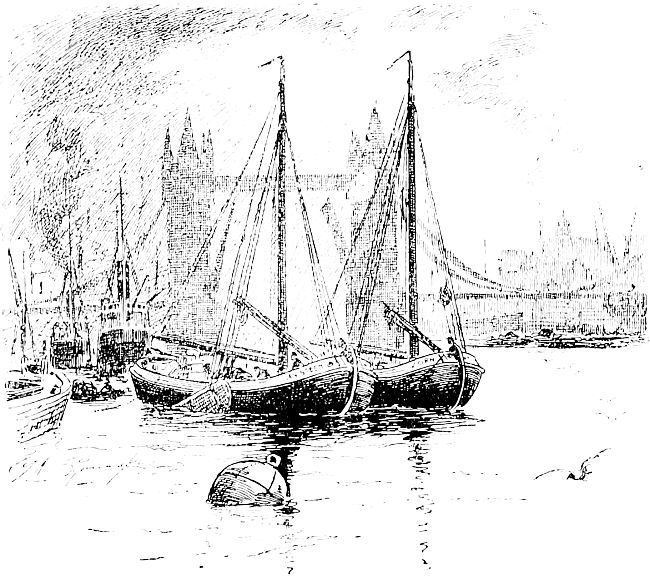

Passing Erith on the Kent coast, and Dagenham and Barking on the Essex, we come to the point where London really begins on its eastward side. From now onwards on each bank there is one long, winding line of commercial buildings, backed in each case by a vast and densely-populated area. On the southern shore come Plumstead and Woolwich, to be succeeded in continuity by Greenwich, Deptford, Rotherhithe, and Bermondsey; while on the northern side come in unbroken succession North Woolwich, Canning Town, and Silvertown (backed by those tremendous new districts—East and West Ham, Blackwall and Poplar, Millwall, Limehouse, Shadwell, and Wapping). In all the eleven miles or so from Barking Creek to London Bridge there is nothing to see but shipping and the things appertaining thereto—great cargo-boats moving majestically up or down the stream, little tugs fussing and snorting their way across the waters, wind-jammers of all sorts and sizes dropping down lazily on the tide, small coastal steamers, ugly colliers, dredgers, businesslike Customs motor-boats and River Police launches, vast numbers of barges, some moving beautifully under their own canvas, some being towed along in bunches, others making their way painfully along, propelled slowly by their long sweeps; there is nothing to hear but the noises of shipping—the shrill cry of the syren, the harsh rattling of the donkey-engines, the strident shouts of the seamen and the lightermen. Everything is marine, for this is the Port of London.

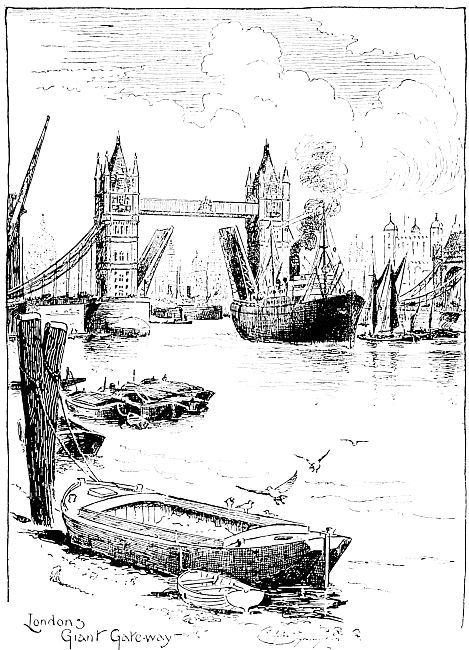

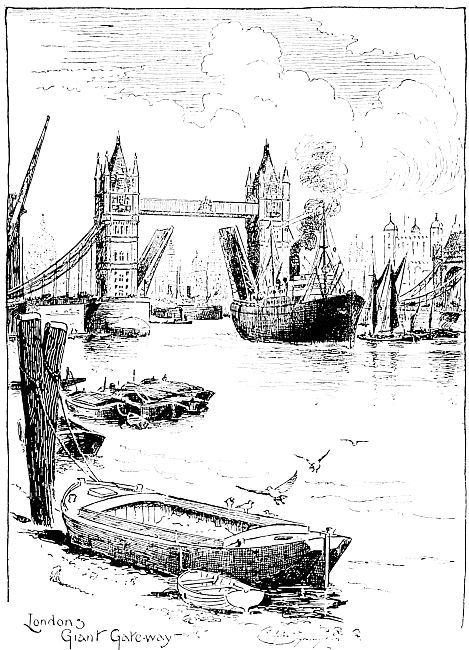

London’s Giant Gateway

Here where the River winds in and out are the Docks, those tremendous basins which have done so much to alter the character of London River during the last hundred years, that have shifted the Port of London from the vicinity of London Bridge and the Upper Pool, and placed it several miles downstream, that have rendered the bascules of that magnificent structure, the Tower Bridge, comparatively useless things, which now require to be raised only a very few times in the course of a day.

In its course from the mouth inwards to the Port the River is steadily narrowing. At Yantlet Creek the stream is about four-and-a-half miles across; but in the next ten miles it narrows to a width of slightly under 1,300 yards at Coalhouse Point at the upper end of the Lower Hope Reach. At Gravesend the width is 800 yards, at Blackwall under 400, while at London Bridge the width at high tide is a little less than 300 yards.

THE POOL.

Just above and just below the Tower Bridge is what is known as the Pool of London. Standing on the bridge, taking in the wonderful picture up and down stream—the wide, filthy London River, with its craft of all descriptions, its banks lined with dirty, dull-looking wharves and warehouses, we find it hard to think of this as the River which we shall see later slipping past Clevedon Woods and Bablock-hythe or under Folly Bridge at Oxford. Up there all is bright and clean and sunny: here even on the blithest summer day there is usually an overhanging pall of smoke which serves to dim the brightest sunshine and add to the dreariness of the scene.

Yet, despite its lack of beauty, despite all the drawbacks of its ugliness and its squalor, this is one of the most romantic places in all England: a place to linger in and let the imagination have free rein. What visions these ships call up—visions of the wonderful East with its blaze of colour and its burning sun, visions of Southern seas with palm-clad coral islands, visions of the frozen North with its bleak icefields and its snowy forest lands, visions of crowded cities and visions of the vast, lonely places of the earth. For these ordinary-looking ships have come from afar, bearing in their cavernous holds the wealth of many lands, to be swallowed up by the ravenous maw of the greatest port in the world.

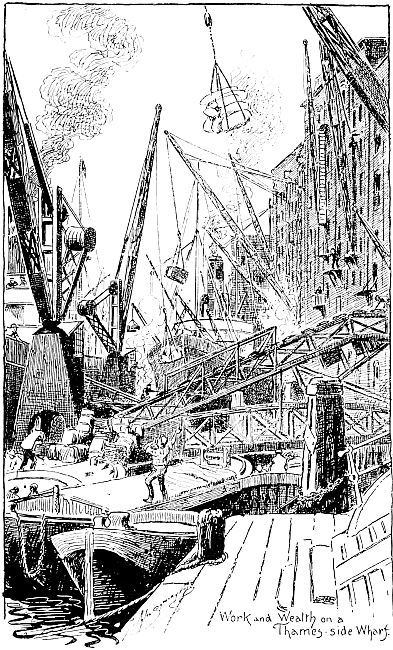

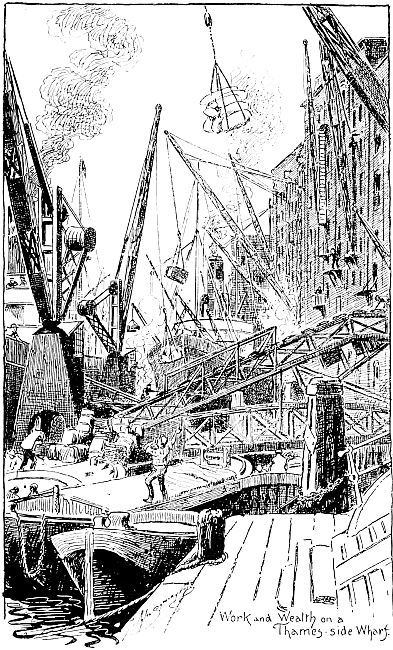

Work and Wealth on a Thames-side Wharf.

Every minute is precious here. Engines are rattling as the cranes lift up boxes and bales from the interiors of the ships and deposit them in the lighters that cluster round their sides. Inshore the cranes are hoisting the goods from the vessels to the warehouses as fast as they can. Men are shouting and gesticulating; syrens are wailing out their doleful cry or screaming their warning note. Everything is hurry and bustle, for there are other cargoes waiting to take the place of those now being discharged, and other ships ready to take the berths of those unloading; and there are tides to be thought of, unless precious hours are to be wasted.

It is a fascinating place, is the Pool, and one which never loses its interest for either young or old.