“par,” which was the score that a professional golfer

The legislation was fortuitous. Following the war, the would achieve on a demanding golf course). In spite nation’s economy boomed, and everyone wanted a

of their considerable clout, not even leaders of the ATA

new car. Between 1945 and 1955, Americans more than

were capable of jump-starting the Interstate Highway

doubled the number of automobiles and trucks on the na-

System.

tion’s streets. In urban areas such as New York, Chicago,

Los Angeles, Dallas, Miami, and Houston, traffic jams,

delays, and accidents spiraled upward. In 1950, the U.S.

President Eisenhower

Chamber of Commerce reported that 40 percent of trip

time in New England cities was wasted in traffic jams.

and the Clay Committee

As traffic delays grew worse, downtown retailers contin-

ued to worry about lost sales to new competitors who

were opening stores in fast-growing suburbs. In spite

President Dwight D. Eisenhower, who

of the Federal-Aid Highway Act, rapid

assumed office in 1953, also failed to

increases in the costs of labor and materi-

break the deadlock over who would pay

als reduced the number of miles actually

the cost of building the IHS. Like his

constructed. Equally important, truck and

contemporaries, Eisenhower wanted to

auto manufacturers built – and Americans

reduce traffic jams, and in principle he sup-

purchased – vehicles that were heavier,

ported the idea of a new highway system.

faster, and longer. If road engineers such

Construction of the IHS over a long period

as MacDonald were to construct a new

of time, Eisenhower and his economic ad-

generation of roads that were safe and ef-

visers believed, would help stimulate the

ficient, then those roads would also have to

U.S. economy. At the same time, however,

be wider, thicker, and far costlier to build

Eisenhower did not want a highway fund-

and maintain. MacDonald estimated that

ing program that would place too great a

the pressure of traffic on the nation’s roads

financial burden on the federal budget.

was eight times greater than in the decades

In August 1954, Eisenhower asked for-

before World War II. As in previous years,

mer U.S. Army General Lucius D. Clay to

leaders of farm, truck, and urban groups

Dwight D. Eisenhower, the likeable ex-

head a committee that would recommend

remained deadlocked over who should pay general who was president for most of the some way of financing an Interstate High-1950s, presided over the creation of the

for these new roads and where they should

Interstate Highway System.

way System. In January 1955, Clay recom-

be located.

mended issuance by the U.S. government

Starting in 1951, leaders of the influential trucking

of $25 billion in bonds that would be retired over 30

industry attempted to break the deadlock in highway

years with funds derived from the federal tax on gasoline

politics. In this period, most trucking firms were small,

and occasional borrowing from the U.S. Treasury. Bond

employing only a few office personnel and fewer than 100

sales to corporations, governments, and private individu-

drivers. The key to truckers’ clout in American politics

als, Clay reasoned, would finance most of the costs of

was their trade association. Headquartered in Washing-

building the IHS without adding to the federal budget

ton, D.C., and with members in every state, the American

or the national debt. Bowing to political reality, Clay pro-

Trucking Associations (ATA) employed talented attor-

posed that the federal government would pay 90 percent

neys who were expert at defending truckers’ interests in

of the costs associated with building the IHS and state

courts and at bringing the concerns of member truckers to

governments would pay 10 percent. Up to that point, the

the offices of senators, representatives, and to the White

federal and state governments had continued to split the

House. Complaining of traffic delays, truck operators still

costs of highway building on a 50-50 basis.

wanted the federal government to spend less money on

Immediately, Clay’s plan was attacked by the same in-

little used rural roads and more money on key routes in

terest groups. Leaders of farm groups objected to Clay’s

and through major cities. During the period 1951-1953,

plan to freeze spending on local farm roads for a period of

they began a lobbying campaign called PAR, which stood

30 years while the bonds were paid off. Equally

for Project Adequate Roads. (Excellent at adapting their

important, the powerful Senator Harry F. Byrd of

42

Virginia did not want the federal government to have to

name of the IHS to the National System of Interstate

pay interest on such a large bond issue.

and Defense Highways. Ordinary Americans have

As an alternative to Clay’s ideas, Representative

called it simply the Interstate Highway System.

George H. Fallon of Maryland prepared legislation that

Finally, in 1956 Congress and the president formally

would have paid directly for highway construction out of

conferred authority on engineers in the U.S. Bureau of

the U.S. federal budget. Fallon’s bill, however, re-

Public Roads and their counterparts in the state high-

quired a vast increase in gasoline and tire taxes. In July

way departments to start the new system by building

1955, nearly 500 truckers went to the nation’s capital to

41,000 miles, including approximately 5,000 urban miles.

complain to senators and representatives about Fallon’s

True to the promise of IHS enthusiasts, by the late

proposal for higher taxes. On July 27, members of the

1980s, the compact IHS carried more than 20 percent

House of Representatives voted to reject both Clay’s

of the nation’s automobile traffic and a whopping 49

proposals and the substitute offered by Fallon. Although

percent of the truck-trailer combinations. In the follow-

the extremely popular President Eisenhower had nar-

ing decades, Congress approved additional mileage for

rowed the range of debate about highway funding, in

the IHS, and by 2002 the rural and urban components

this instance he could not translate that popularity into

of the total system stood at 47,742 miles. By early 2004,

a formula that satisfied the many

the federal government had spent

competitors for highway-construc-

more than $59 billion to construct

tion dollars.

urban portions of the IHS and

more than $40 billion to construct

Solution

the rural sections.

to Deadlock:

Protests and More

a Highway Trust

Local Control

Fund

The construction of a vast new

highway system affected the

lives of millions of people. While

In 1956, Senator Albert Gore

many welcomed the new roads,

Sr., of Tennessee and Repre-

others disliked them as symbols of

sentative Hale Boggs of Louisiana

runaway modernity that chewed

joined with Representative Fallon

up landscape and/or urban areas.

to make yet another attempt to

Protests against highway build-

pass IHS legislation. The key to

ing led Congress to shift control

their success was in providing a

of highway construction away

little something for all interests:

Some say the IHS vastly improved America; others believe it from state and federal engineers.

more spending for rural, urban, and led to more suburban sprawl, ugliness, and traffic congestion As early as 1959, residents and interstate highways, but all this

– as here at a bad moment on Interstate 95 near Washington,

political leaders in San Fran-

accomplished with only a small in- D.C. Liked or disliked, the system defined American modernity. cisco blocked construction of the crease in gasoline and other automotive and truck taxes.

Embarcadero Freeway. Starting in 1962, residents of

As part of this arrangement, Congress and Eisenhower

Baltimore banded together to protect city neighborhoods

approved creation of the Highway Trust Fund, which

from destruction by highway engineers. In the late 1960s

would designate gasoline taxes (and excise taxes on tires

and early 1970s, upper-income residents of Northwest

and trucks) for exclusive use in financing construction

Washington, D.C., made use of political savvy and legal

of the IHS and other federal-aid roads. No longer would

know-how to block construction of the Three Sisters

truck operators complain about gasoline taxes used for

Bridge across the Potomac River. Authors of books with

non-highway purposes. To build public support for the

titles such as The Pavers and the Paved and Superhighway-

final agreement, early in 1956 members of the Senate-

Superhoax attracted national attention to this “freeway

House conference committee officially changed the

revolt” taking place.

43

In response to this resistance at the local level, in 1973,

The construction of the Interstate Highway System

Congress and President Richard M. Nixon approved the

produced important consequences in the American

Federal-Aid Highway Act, which fi nanced local purchase

future. The vast new ribbons of concrete helped speed

of buses and fi xed rail systems with money taken from

up the process whereby millions of Americans moved

the formerly inviolable Highway Trust Fund. In 1991,

from central cities to suburbs. By 1970, the United

Congress and President George H.W. Bush approved

States was already a “suburban nation.” Equally impor-

the Intermodal Surface Transportation Effi ciency Act

tant, the system (along with the postwar development

(ISTEA). Now, local political leaders in metropolitan

of television, public schools, and the existing network

planning organizations could have a say in choosing

of roads) was catalytic in knitting together the economic

whether to spend a portion of federal and state funds on

and social outlooks of more than 290 million persons.

highways, public transit, bike paths, or other projects.

Accents, diets, and customs became less regional, more

Passage of ISTEA comprised an important element in

national. Nearly as important, construction of the IHS

the devolution of federal highway funds and authority

permitted truck operators to displace the nation’s

from national and state engineering experts to local politi-

railroads in competition for prompt delivery of food,

cians.

furniture, refrigerators, and everything else.

Whether under construction (above) or

complete (inset), superhighways now

carry Americans ceaselessly day and

night, on business or pleasure.

44

While railroads still maintained their own trackbeds,

social cohesion, and the reorientation of politics and

in effect the government had fi nanced truckers’ right-

public policy in the United States.

of-way. In terms of political consequences, after 1970

the federal highway program was devolved to the states

Mark H. Rose is a professor of history at Florida Atlantic University. He is and localities, setting a pattern for similar attempts in

the author of more than 30 articles and several books, including: The Best areas such as social welfare spending. To this day, the

Transportation System in the World: Railroads, Trucks, Airlines, and

Interstate Highway System remains the nation’s greatest

American Public Policy in the Twentieth Century , with Bruce E. Seely

public works project. It was a successful intersection

and Paul Barrett. Rose is also co-editor of Business, Politics, and Society , a between politics and commerce; an experiment that had

book series published by the University of Pennsylvania Press.

notable consequences for transportation, urban change,

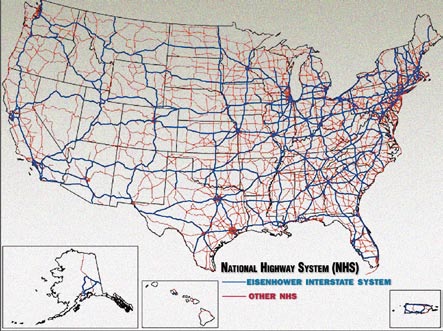

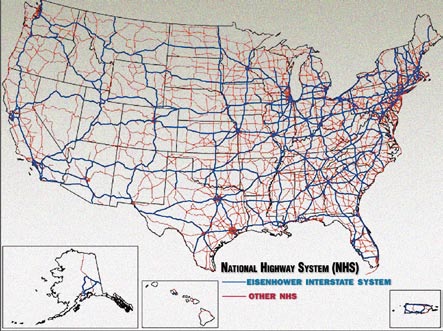

In this map, the Interstate highway system is limned in blue, showing how it linked the nation.

45

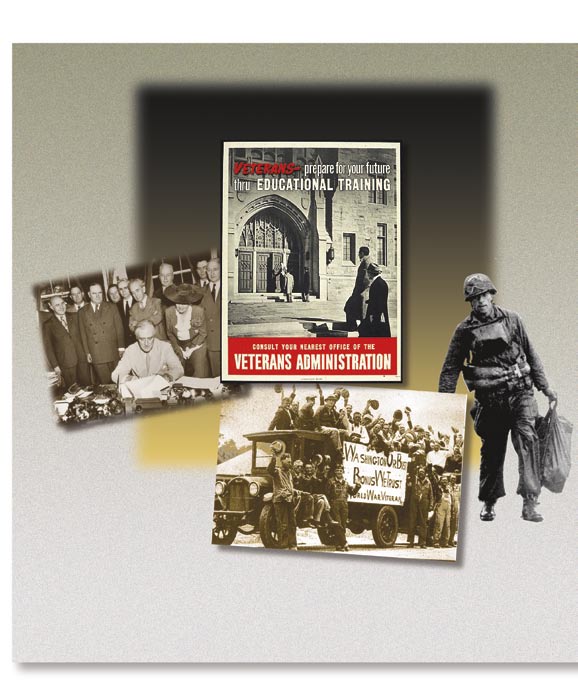

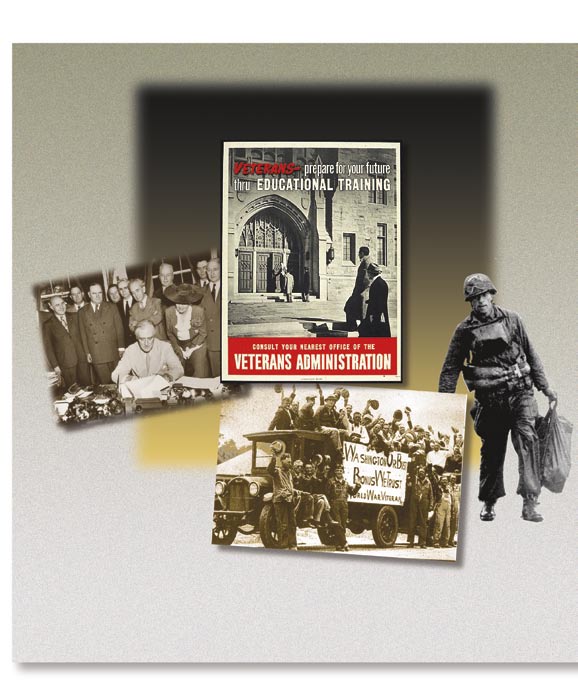

When the “Bonus Boys” – demobilized soldiers

of World War I – seen here in a crowded

truck, converged on Washington in 1932, they

were suppressed by the army.

World War II vets, in contrast, were offered

mass access to higher education through

the “GI Bill,” signed in 1944 by President

Franklin D. Roosevelt. Education of

returning troops saved a generation and put

America on the road to the boom

of the ‘50s.

46

by Milton Greenberg

The

GI Bill of Rights

THE GI BILL OF RIGHTS, OFFICIALLY KNOWN AS THE

SERVICEMEN’S READJUSTMENT ACT OF 1944, WAS SIGNED

INTO LAW ON JUNE 22, 1944, BY PRESIDENT FRANKLIN D.

ROOSEVELT. AT THE TIME, ITS PASSAGE THROUGH

CONGRESS WAS LARGELY UNHERALDED, IN PART BECAUSE

THE NORMANDY INVASION WAS UNDER WAY; BUT ALSO

BECAUSE ITS FUNDAMENTAL SIGNIFICANCE AND MAJOR

CONSEQUENCES FOR AMERICAN SOCIETY COULD NOT HAVE

BEEN FORESEEN. HOWEVER, WITH THE END OF THE WAR

IN BOTH EUROPE AND ASIA JUST A YEAR LATER, THE GI

BILL’S PROVISIONS WOULD SOON BE QUICKLY AND

FULLY TESTED. WITHIN A FEW YEARS, THE NEW LAW SERVED

TO CHANGE THE SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC LANDSCAPE OF

THE UNITED STATES.

47

Among its provisions, the law made available to World of World War I, exacerbated by deteriorating economic War II veterans immediate financial support in the

conditions, had led to protest marches and disastrous

form of unemployment insurance. Far more important,

confrontations. In 1932, 20,000 veterans gathered in

as it turned out, were generous educational opportunities

Washington, D.C., for a “bonus march,” hoping to obtain

ranging from vocational and on-the-job training to higher

financial rewards they thought they had been promised

education, and liberal access to loans for a home or a busi-

for service in World War I, leading to one of America’s

ness.

most tragic moments. Altercations led President

While there were numerous bills introduced in Con-

Hoover to call out the army, which under the leadership

gress to reward the combat-weary veterans of World War

of future military heroes General Douglas MacArthur

II, this particular bill had a significant sponsor. The

and Majors Dwight Eisenhower and George Patton used

major force behind the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act

guns and tanks against the “bonus army.”

of 1944 was the well-known American Legion, a private

In the minds of Washington policymakers who had

veterans advocacy group founded in 1919. The Legion,

witnessed this confrontation, the viable legislation to

during its 25th annual convention in September 1943,

meet the needs of veterans that emerged in 1944 came

initiated its own cam-

not a moment too soon.

paign for comprehensive

Even when it was clear

support of veterans. It

that the Allies were going

labeled the resulting

to win, few foresaw the

ideas, crafted into one

complete capitulation of

legislative proposal by

the Axis powers one year

the Legion’s national

later with the dropping of

commander Harry W.

the atomic bomb on Hiro-

Colmery, “a bill of rights

shima and Nagasaki, and

for GI Joe and GI Jane,”

the sudden return of more

but the proposal soon

than 15 million veterans

became known as the GI

of the Army, the Navy,

Bill of Rights. The term

and the Marine Corps,

GI – the slang term for

streaming home from

American soldiers in that

the Atlantic and Pacific

war – originally stood

theaters.

for “Government Is-

We must remember

sue,” referring to military

that for 12 years prior to

regulations or equipment.

the Japanese bombing

Wedded to the idea of

attack on the U.S. naval

the “Bill of Rights” in the

base in Pearl Harbor,

revered U.S. Constitution,

Hawaii – the attack that

the “GI Bill” was bound

drew America into World

to project an appealing

War II – America was in

These were the lucky ones – men who survived World War II –

aura in the halls of Con-

returning home from Europe on a troop ship in 1945. The GI Bill would make it a deep economic depres-gress as politicians sought

easier for them to rejoin civilian life.

sion. Thus, the war,

ways to reward the homebound soldiers.

when it came, found the nation unprepared and largely

But there is more to the story. Though it might appear

uneducated, faced with the need to build a fighting force

that the adoption and passage of the bill was entirely the

of young people who had known only the Great Depres-

result of unbridled generosity on the part of a grateful

sion years. Unemployment was widespread, with 25

Congress, it was also in large measure a product of justi-

percent of the workforce unemployed at the height of

fied concern, even a certain fear, on the part of lawmak-

the depression in 1933. Breadlines and soup kitchens

ers about a radicalized postwar America. Prior to World

for even formerly prosperous middle-class men personi-

War II, America had provided benefits and care to those

fied the era, and entire families thought they faced a life

disabled by combat, but had paid little attention to its

of poverty and joblessness. Most of the industrialized

able-bodied veterans. Within living memory of many

world in one way or another was caught up in the same

public men of the time, neglect of the returning veterans

calamity, with disastrous political results, including the

48

rise of totalitarian regimes in crisis-ridden nations around

basis to blacks and whites. In the mid-1940s, $20 was a

the world.

lot of money. For 15 cents or even less, one could buy

Though the New Deal government of President

gasoline, cigarettes, beer, milk shakes, or go to a movie.

Franklin D. Roosevelt, first elected in 1932, initiated

Yet – and this is indicative of that generation’s response

numerous governmental programs that generated some

to the war’s end, and the stigma in those days that came

employment, 10 million people, or about 17 percent of

with accepting public money – only slightly more than

the workforce, were still unemployed in 1939. The out-

half the veterans even claimed the money; and most

break of the war in Europe in 1939 brought forth a new

used it for so few weeks that less than 20 percent of the

surge of economic activity as well as an ensuing military

estimated cost was actually spent.

draft. Ironically, it was the American entry into the war

For educational benefits, the method was for the

in late 1941 that put an end to the Great Depression, by

Veterans Administration (VA) to certify eligibility, pay

taking young men temporarily out of circulation as most

the bills to the school for tuition, fees, and books, and

went into the military and putting everyone else to work

to mail a monthly living stipend to the veteran for up

on the home front, including large numbers of women.

to 48 months of schooling, depending upon length of

The American Legion, strongly supported by William

service. For home loans for GIs, the VA guaranteed a

Randolph Hearst and his chain of newspapers, waged

sizeable portion of the loan to the lending institution

their campaign for the GI Bill by stressing fear of a return

and mortgage rates were set at a low 4 percent interest.

to prewar breadlines and resulting threats to democracy.

The formal aspects of these programs have lived on in

subsequent, though less generous, versions of the GI

Bill for Korean War and Vietnam War veterans – and still

Same Rules for All

continue as an enlistment incentive for America’s cur-

rent volunteer military under what is now known as the

In spirit, as well as specific provisions, the GI Bill was Montgomery GI Bill.